Jean-Léon Gérôme

Jean-Léon Gérôme | |

|---|---|

Academicism, Orientalism |

Jean-Léon Gérôme (French pronunciation:

Early life

Jean-Léon Gérôme was born at

His painting

Gérôme abandoned his dream of winning the Prix de Rome and took advantage of his sudden success. His paintings The Virgin, the Infant Jesus and Saint John and Anacreon, Bacchus and Eros took a second-class medal at the

In 1851, he decorated a vase later offered by Emperor

Important commissions

In 1852, Gérôme received a commission to paint a large mural of an allegorical subject of his choosing. The Age of Augustus, the Birth of Christ, which combined the birth of Christ with conquered nations paying homage to Augustus, may have been intended to flatter Napoleon III, whose government commissioned the mural and who was identified as a "new Augustus."[5][6] A considerable down payment enabled Gérôme to travel and research, first in 1853 to Constantinople, together with the actor Edmond Got, and in 1854 to Greece and Turkey and the shores of the Danube, where he was present at a concert of Russian conscripts making music under the threat of a lash.[7]

In 1853, Gérôme moved to the Boîte à Thé, a group of studios in the Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, Paris. This became a meeting place for artists, writers and actors, where George Sand entertained the composers: Hector Berlioz, Johannes Brahms and Gioachino Rossini and the novelists Théophile Gautier and Ivan Turgenev.

In 1854, he completed another important commission, decorating the Chapel of St. Jerome in the

To the Universal Exhibition of 1855 he contributed Pifferaro, Shepherd, and The Age of Augustus, the Birth of Christ, but it was the modest painting Recreation in a Russian Camp that garnered the most attention.[3]

Orientalism

In 1856, Gérôme visited Egypt for the first time. His itinerary followed the classic Grand Tour of the Near East, up the Nile to Cairo, across to Faiyum, then further up the Nile to Abu Simbel, then back to Cairo, across the Sinai Peninsula through Sinai and up the Wadi el-Araba to Jerusalem and finally Damascus.[8] This heralded the start of many Orientalist paintings depicting Arab religious practice, genre scenes and North African landscapes.

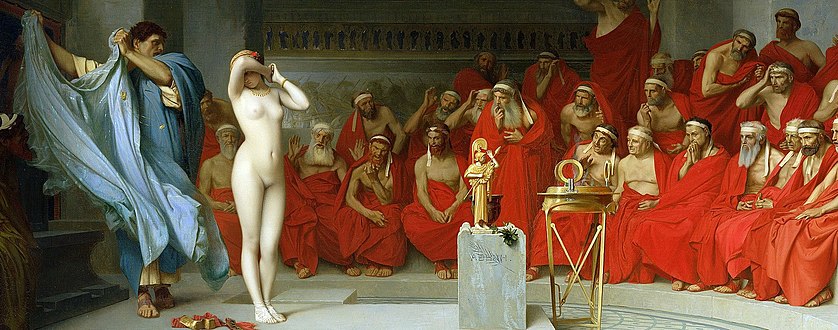

Among these are paintings in which the Oriental setting is combined with depictions of female nudity.

In his travels, Gérôme collected artefacts and costumes for staging oriental scenes in the studio, and also made oil studies from nature for the backgrounds. In an autobiographical essay of 1878, Gérôme described how important oil sketches made on the spot were for him: "Even when worn out after long marches under the bright sun, as soon as our camping spot was reached I got down to work with concentration. But Oh! How many things were left behind of which I carried only the memory away! And I prefer three touches of color on a piece of canvas to the most vivid memory, but one had to continue on with some regret."[12]

Gérôme's reputation was greatly enhanced at the

Return to Classical subjects

In 1858, he helped to decorate the Paris house of Prince

In Ave Caesar! Morituri te Salutant, shown at the Salon of 1859, Gérôme returned to the painting of Classical subjects, but the picture failed to interest the public. King Candaules (1859) and

In 1863, he married Marie Goupil (1842–1912), the daughter of the international art dealer Adolphe Goupil. They had four daughters and one son. His oldest daughter was Jeanne (1863-1944) and she was followed by Suzanne (1867-1941; married to Aimé Morot), Blanche (1868-1918) and Madeleine (1875-1905). Upon his marriage he moved to a house in the Rue de Bruxelles, close to the Folies Bergère. He expanded it into a grand house with stables with a sculpture studio below and a painting studio on the top floor.[3]

Atelier at École des Beaux-Arts

Gérôme was appointed as one of the three professors at the École des Beaux-Arts. He started with sixteen students. Between 1864 and 1904, more than 2,000 students received at least some of their art education through Gérôme's atelier at the École des Beaux-Arts. Places in Gérôme's atelier were limited, keenly sought and highly competitive. Only the best students were admitted and aspirants considered it an honour to be selected. Gérôme progressed his students through drawing from antique works, casts and followed by life study with live models generally selected on the basis of their physique, but occasionally for their facial expression in a sequence of exercises known as the academie. Students drew parts of a bust before the entire bust, then parts of the live model before preparing full figures. Only when they had mastered sketching were they permitted to work in oils. They were also taught to draw clearly and correctly before consideration of tonal qualities. In his school, the floor sloped so that students had the fullest view of the model from the rear of the room. Students sat around any model in order of seniority, with the more senior students towards the rear so that they could draw the full figure, while the more junior members sat towards the front and concentrated on the bust or other part of the anatomy.[14]: 17–21

According to John Milner, who studied with Gérôme, his atelier was the most "riotous" and "lewd" of all the studios at Beaux-Arts. Students were treated to bizarre initiation rites which included slashing each other's canvases, throwing students down stairs, out of windows, and onto upturned stools, staging fencing matches on the model's dais, in the nude and with paintbrushes loaded with paint.[14]: 17-18

Gérôme attended every Wednesday and Saturday, demanding punctilious attendance to his instructions. His reputation as a severe critic was well-known. One of his American students, Stephen Wilson Van Shaick, commented that Gérôme was "merciless in judgement" yet possessed a "singular magnetism."

Honors and mid-career works

Gérôme was elected, on his fifth attempt, a member of the

The Execution of Marshal Ney was exhibited at the Salon of 1868. On behalf of Ney's descendants, Gérôme was asked to withdraw the painting, but did not comply. The general reception was very split and the 1868 Salon marked the beginning of a lasting divide between Gérôme and many French art critics, who accused him of relying on literary techniques, of commercialising art, and of bringing politics into art. Henri Oulevay made a caricature where Gérôme is depicted in front of the wall with the art critics as the firing squad.[17]

In 1872 Gérôme produced Pollice Verso, a painting of bloody gladiators and blood-thirsty Vestal virgins in the Colosseum that became one of his most famous works. Alexander Turney Stewart purchased the painting from Gérôme at a price of 80,000 francs, setting a new record for the artist.[18] Gérôme's imagery of the turned thumb to signal life or death for a fallen gladiator was repeated in a multitude of movies, from the silent era up to and including the 2000 Oscar-winner Gladiator.[19][20]

Gérôme returned successfully to the Salon in 1873 with his painting L'

From approximately 1876 to 1890, Gérôme frequently worked with model Emma Dupont, who posed for several of his works, including Nude (Emma Dupont) (1876), The End of the Sitting (1886), Omphale (1887), Working in Marble, or The Artist Sculpting Tanagra (1890), and Tanagra (1890).[22]

Sculpture

In his thirties, Gérôme took up sculpture. His first work was a large bronze statue of a gladiator holding his foot on his victim, based on his painting Pollice Verso (1872) and shown to the public at the Universal Exhibition of 1878. The same year he exhibited a marble statue at the Salon of 1878, based on his early painting Anacreon, Bacchus and Eros (1848).

Aware of contemporary experiments of tinting marble (such as by those by John Gibson), he produced Dancer with Three Masks combining movement with color, first exhibited in 1902 and now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Caen.

Among his other sculptures are

He experimented with mixed ingredients, using for his statues tinted marble, bronze and ivory inlaid with precious stones and paste. His Dancer was exhibited in 1891. His lifesize statue Bellona, in ivory, bronze, and gemstones, attracted great attention at the 1892 exhibition in the

Gérôme then began a series of conquerors, wrought in gold, silver and gems: Bonaparte Entering Cairo (1897), Tamerlane (1898), and Frederick the Great (1899).[3]

In 1903 Gérôme executed a two sculpture commission,

Gérôme and Impressionism

During the last decades of his career, as his own work fell out of fashion, Gérôme was harshly critical of

The

Monet, do you remember his cathedrals? And that man used to know how to paint! Yes, I've seen good things by him, but now![4]

Similarly he objected to the

Late career: the Pygmalion–Tanagra cycle

Beginning in 1890, Gerome again drew inspiration from the ancient world with an interconnected, slyly self-referential series of paintings and sculptures that depicted

In 1890, Gérôme made at least two paintings of the mythical Greek sculptor Pygmalion kissing his statue of Galatea at the very moment she is transformed from marble into living flesh. The most famous of these paintings titled Pygmalion and Galatea is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art; it shows the sculptor and his living statue from the rear. A variation (in private hands) shows them from the front.

Also in 1890, responding to widespread fascination with the ancient

Gérôme subsequently created smaller, gilded bronze versions of Tanagra; several versions of the "Hoop Dancer" figurine held by Tanagra (these became "Gérôme's most popular and widely reproduced sculpture"[25]); two paintings of an imaginary ancient Tanagra workshop where copies of his own Hoop Dancer are on display; and two self-portraits of himself sculpting Tanagra from a living model in his Paris atelier, in which a Hoop Dancer and two different versions of Pygmalion and Galatea can be seen in the background. This complex self-portrait has been called "a summation of Gérôme's remarkable career as both painter and sculptor."[24]

Gérôme also sculpted a tinted-marble Pygmalion and Galatea (1891) based on his paintings.[3]

In this cycle of works, with its exploration of

Truth—"This is our Mona Lisa"

Beginning in the mid-1890s, in the last decade of his life, Gérôme made at least four paintings personifying Truth as a nude woman, either thrown into, at the bottom of, or emerging from a well. The imagery was inspired by an aphorism of the philosopher Democritus, "Of truth we know nothing, for truth is in a well."[26]

Gérôme himself invoked the metaphor of Truth and the well in a preface he wrote for Émile Bayard's Le Nu Esthétique, published in 1902, to characterize the profound and irreversible influence of photography:

La photographie est un art. La photographie force les artistes à se dépouiller de la vieille routine et à oublier les vieilles formules. Elle nous a ouvert les yeux et forcé à regarder ce qu'auparavant nous n'avions jamais vu, service considérable et inappréciable qu'elle a rendu à l'Art. C'est grâce à elle que la vérité est enfin sortie de son puits. Elle n'y rentrera plus.

Photography is an art. It forces artists to discard their old routine and forget their old formulas. It has opened our eyes and forced us to see that which previously we have not seen; a great and inexpressible service for Art. It is thanks to photography that Truth has finally come out of her well. She will never go back.[31]

In 2012, the Musée Anne de Beaujeu in Moulins, France, which now owns the painting, mounted the exhibition La vérité est au musée ("Truth is at the Museum"), which collected numerous drawings, sketches, and variants made by Gérôme, and by other artists, relating to the painting and its theme.[32] The multiple interpretations of the painting's enigmatic meaning prompted one of the museum's curators to say, "C'est notre Joconde à nous." ("This is our Mona Lisa.")[29]

Death

By the end of his life, Gérôme felt very much a man out of his time. In 1903, recalling his first meeting with Charles Jalabert in 1840, he wrote:

At that time, Paris had nothing to do with the Paris of today: no railways, no bicycles, no cars; we were less agitated, and certain districts, among others the one we lived in and which we called the Latin Quarter, had a provincial aspect in their calm and tranquility. Now everything is changed; we no longer walk, we run like crazy; if we are not crushed during the day, we have a good chance of being murdered at night. It is charming. We have witnessed the end of a world, we are witnessing the dawn of a new one, which lacks the picturesque and above all serenity. The day is not far off when, through our customs, our ways of being, our love of the dollar (auri sacra fames), we will no longer be French, neither in spirit nor in heart. Horrible to think of! We will be Americans![33]

On 31 December 1903, Gérôme wrote to his student and former assistant Albert Aublet, "I begin to have enough of life. I've seen too much misery and misfortune in the lives of others. I still see it every day, and I'm getting eager to escape this theatre." He was to live just ten more days.[4]

On 10 January 1904, "the maid found him dead in the little room next to his atelier, slumped in front of a portrait of Rembrandt and at the foot of his own painting Truth"—but the source for this anecdote, the biographer Moreau-Vauthier, does not specify which painting of Truth.[4][34] He was 79.

At his own request, he was given a simple burial service without flowers. But the

Legacy

Gérôme's legacy lived on through the works of his thousands of students from many countries, including:

Gérôme's prodigious energy, long career, and wide popularity resulted in an enormous body of work that now resides in museums and private collections around the world; Ackerman's revised catalogue raisonné of 2018 lists approximately 700 paintings and 70 sculptures.[38]

In the early 1870s Gérôme was known for an astonishing range of visual exotica, all realized in precise, minute detail, achieved with thin layers of paint that revealed nary a brushstroke...His works were particularly sought after by wealthy Americans...Over the course of his career, Gérôme sold to American patrons 144 paintings, nearly a quarter of his production. [A work by Gérôme in the

San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906.[39]] Despite his prodigious output and enormous transatlantic success, most scholarly articles of recent decades cite Gérôme's work as a noxious blend of the trite, the exploitative and the stultifying academic. However, the latest scholarship is re-evaluating Gérôme and his importance in the nineteenth century. A 2010 essay by art historian Mary G. Morton[40]...points out that, contrary to most twenty- and twenty-first century perspectives...Americans [in the 1800s] found Gérôme's paintings complex, edifying and completely modern.[41]

His well-researched and minutely detailed images of gladiator combats, chariot races, slave markets, and many other subjects from the ancient world created an indelible impression on popular culture.

His ethnographic imagery of Arab and Islamic culture, controversial in his own lifetime, is now even more closely scrutinized, as is his penchant for female nudity; modern critics raise issues of "cultural appropriation" and "sexual exploitation".

Despite charges that the Orientalizing paintings of Gérôme (and others) exploited and indulged in stereotypes of Arab and Muslim cultures, there is now "a high level of interest in collecting Gérôme's art in the Middle East," as evinced by high prices paid at auction for his work by the

Gérôme's highly vocal opposition to Impressionism was a losing argument, and his work was relegated to the margins of art history by critics, historians, and museum professionals who believed that

his chosen themes corrupted the loftier purposes of art, thus leading to commercialism...they also objected to his orientalism, which they disparaged for being untrue, a perversion or concoction of the true Orient....Now, with the exhibition at the Getty Museum, and a larger version of the show opening at the Musée d'Orsay in October 2010, Gérôme is finally receiving the attention he deserves. No longer will he be lost in time, although his paintings, the way he developed them, and his relationship with many of the major issues of artistic creativity in the nineteenth century and beyond will remain controversial.[45]

As with other painters of

The most wide-ranging single collection of Gérôme's work may be the several rooms dedicated to displaying his paintings and sculptures at the Musée Georges-Garret in the artist's hometown of Vesoul. Gérôme donated several works to the museum during his lifetime, and his heirs donated more works after his death.

Gallery (chronological)

-

Kunsthalle Hamburg

-

The Tryst (exterior), after 1840, Saint Louis Art Museum

-

The Tryst (interior), after 1840, Saint Louis Art Museum

-

Saint Vincent de Paul, 1847, Musée Georges-Garret, Vesoul

-

Portrait of Claude-Armand Gérôme (brother of the artist), 1848,The National Gallery, London

-

Portrait of Claude-Armand Gérôme (brother of the artist), c.1848, Fitzwilliam Museum

-

The Virgin, the Infant Jesus and Saint John, 1848, private collection

-

Anacreon, Bacchus, and Eros, 1848, Musée des Augustins

-

Portrait of a Woman, 1848, Art Institute of Chicago

-

La République, 1848–1849, Petit Palais, Paris

-

Portrait of a Lady, 1849,Musée Ingres

-

Michelangelo Being Shown the Belvedere Torso, 1849, Dahesh Museum of Art

-

Gynaeceum or ancient Greek Interior, 1850

-

A Soul Carried Away by an Angel, 1853, Musée Georges-Garret, Vesoul

-

An Idyll (Daphnis and Chloe), 1858, Musée Massey

-

Buying a Slave, 1857; provenance discussed by Sarah Lees[9]

-

Egyptian Recruits Crossing the Desert, 1857

-

At Prayer,1858

-

Wallace Collection, London, 1859

-

Wallace Collection, London, 1859

-

The Duel After the Masquerade, version of 1859, Walters Art Museum

-

King Candaules, 1859, Museo de Arte de Ponce

-

Diogenes, 1860, Walters Art Museum

-

Socrates Seeking Alcibiades in the House of Aspasia, 1861

-

The Christian Martyrs' Last Prayer, 1863, Walters Art Museum

-

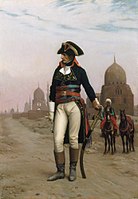

Napoleon in Egypt, c. 1863, Princeton University Art Museum

-

Prayer in the Desert, 1863, private collection

-

Young Greeks at the Mosque, 1865, Minneapolis Institute of Art

-

Arnaut Smoking, 1865

-

Evening Prayer, Cairo, 1865, private collection

-

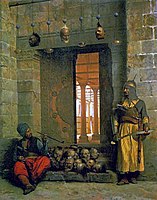

Heads of the Rebel Beys at the Mosque of El Hasanein, Cairo, 1866

-

The Muezzin, 1866, Joslyn Art Museum

-

Cleopatra and Caesar, 1866, private collection

-

On the Desert, before 1867, Walters Art Museum

-

The Horse Market, 1867, Haggin Museum

-

Bashi-Bazouk, 1868–1869, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Bashi-Bazouk, 1869, Metropolitan Museum of Art[49]

-

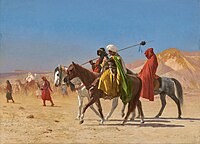

Riders Crossing the Desert, (1870), private collection

-

The Harem in the Kiosk, c. 1870–1875, private collection

-

Rider and his Steed in the Desert, 1872, private collection

-

Pool in a Harem, 1876, Hermitage Museum

-

Femme circassienne voilée, 1876,Qatar Museums Authority

-

The Standing Bearer, Unfolding the Holy Flag, 1876, Haggin Museum

-

Chariot Race, 1876, Art Institute of Chicago

-

Reception ofLe Grand Condé at Versailles, 1878, Musée d'Orsay

-

The Gladiators, bronze, 1878, photogravure Goupil c. 1892

-

The Snake Charmer, c. 1879, Clark Art Institute

-

The Wailing Wall, 1880, Israel Museum

-

Cave Canem, 1881, Musée Georges-Garret

-

Arnaut Blowing Smoke in His Dog's Nose, 1882, private collection

-

The Grief of the Pasha, 1882, Joslyn Art Museum

-

The Saddle Bazaar, Cairo, 1883, Haggin Museum

-

The Two Majesties, 1883, Milwaukee Art Museum

-

Slave Market in Ancient Rome, c. 1884, Hermitage Museum

-

A Roman Slave Market, c. 1884, Walters Art Museum

-

The Bath, 1880–1885, Legion of Honor, San Francisco

-

The Large Pool of Bursa, 1885, private collection

-

Bonaparte Before the Sphinx, aka Œdipe, 1886, Hearst Castle

-

La fin de séance (The End of the Session), 1886, private collection

-

The Carpet Merchant, c. 1887, Minneapolis Institute of Art

-

Tiger on the Watch, c. 1888, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

-

The Birth of Venus, 1890, private collection

-

La Danse Pyrrhique, c. 1890, private collection

-

Pygmalion and Galatea, c. 1890

-

Prayers in the Mosque, 1892, private collection

-

The Antique Pottery Painter: Sculpturæ vitam insufflat pictura (painting breathes life into sculpture), 1893, Art Gallery of Ontario

-

Tanagra Workshop, 1893, private collection

-

Hoop Dancer, c. 1890, Haggin Museum, seen in his painting The Artist and His Model

-

The Artist and His Model, 1895, Haggin Museum; Gérôme depicts himself sculpting Tanagra

-

Sarah Bernhardt, marble, c. 1895, Musée d'Orsay

-

Leda and the Swan, 1895

-

Mendacibus et histrionibus occisa in puteo jacet alma Veritas, 1895, location unknown

-

Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon

-

Bonaparte Entering Cairo, 1897

-

Entry of the Christ at Jerusalem, 1897, Musée Georges-Garret, Vesoul

-

The Story of Anacreon 1: Cupid at the Door in a Rainstorm, c. 1899, private collection[50]

-

The Story of Anacreon 2: Young Love's Shivering Limbs the Embers Warm, c. 1899, private collection

-

The Story of Anacreon 3: Cupid Runs out the Door, c. 1899, private collection

-

The Story of Anacreon 4: The Poet Dreams of Cupid by the Fire, c. 1899, private collection

-

Souvenir of Achéres, 1903, Columbus Museum of Art

Images of Gérôme

-

Jean-Léon Gérôme, self-portrait c. 1844, Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University

-

Eugène Giraud, caricature of Gérôme, between 1858 and 1870

-

Robert Jefferson Bingham, portrait of Gérôme, between 1860 and 1875

-

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Bust of Jean-Léon Gérôme, after 1871, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

-

Jules-Clément Chaplain, Jean-Léon Gérôme medal, 1885, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Self-portrait, 1886, Aberdeen Art Gallery

-

Jean-Léon Gérôme in his Paris studio, c. 1885-1890

-

Self-portrait, painting The Ball Player, 1902, Musée Georges-Garret, Vesoul

See also

- List of Orientalist artists

- List of pupils of Jean-Léon Gérôme

- Société des Peintres Orientalistes Français (Society of French Orientalist Painters)

References and sources

References

- ^ Beeny 2010, p. 42

- ^ Besson, Nicolas François Louis. Les Annales Franc-Comtoises, vol. 11. Printed by Paul Jacquin in Besançon, 1899. pp. 255-56. Retrieved on Google Books, Oct. 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chisholm, Hugh, ed. "Gérôme, Jean Léon", Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University, 1901.

- ^ a b c d e "The Whirling Dervish". stairsainty.com.

- ^ "Siècle d'Auguste : Naissance de N.S. Jésus Christ". www.musee-orsay.fr.

- ^ "The Age of Augustus, the Birth of Christ". getty.edu.

- ISBN 0918098149

- ^ Gerald M. Ackerman: Jean-Léon Gérôme: Eight Oil Sketches. 5 December 2004

- ^ a b Lees, Sarah, ed. (2012). Nineteenth-Century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute (excerpt: "The Slave Market") (PDF). pp. 359–363.

- ^ e.g. Nochlin (1983); Toledano (1998, 4–6); Lees (2012)

- ^ a b Grieshaber, Kirsten (30 April 2019). "US museum condemns use of its art by German far-right party". www.apnews.com. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Gérôme, Notes, "J. L. Gérôme á la montée de sa carrière, fait la balance", in: Bulletin de la société d'agriculture, lettres, sciences et arts de la Haute-Saône, 1980, pp. 1–30

- ^ "Musée Condé". Suite d'un bal masqué. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d O'Sullivan, N. Aloysius O'Kelly: Art, Nation, Empire. Field Day Publications, 2010.

- ^ "Jean Leon Gerome | American Academy of Arts and Sciences". www.amacad.org. 9 February 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, pp. 97–99

- ^ DeCourcy E. McIntosh, "Goupil and the American Triumph of Jean-Léon Gérôme", in Musée Goupil, Gérôme and Goupil: Art and Enterprise, trans. Isabel Ollivier. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2000, p. 38.

- ^ Spier, Christine (6 August 2010). "Thumbs Up or Thumbs Down? Looking at Gérôme's "Pollice Verso"". blogs.getty.edu/iris. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ Diana Landau, editor. Gladiator: The Making of the Ridley Scott Epic. New York: Newmarket, 2000, p. 26.

- ^ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: L'Eminence Grise

- ^ a b c Waller, Susan (2014). "Jean-Léon Gérôme's Nude (Emma Dupont): The Pose as Praxis". Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide. 13 (1).

- ^ "Highlights of Allentown Art Museum Works in the Community". 18 December 2010.

- ^ a b c "Jean-Léon Gérôme (French, 1824–1904) Working in Marble, or The Artist Sculpting Tanagra, 1890". daheshmuseum.org. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Susan Moore (16 May 2018). "The diminutive dancing girl who made a big impression". apollo-magazine.com. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Diogenes Laertius. Lives of Eminent Philosophers. IX, 72. Perseus Project, Tufts University.

- ISBN 9780856673115.

- ISBN 9782811107901.

- ^ a b "Exposition autour de "La Vérité" de Jean-Léon Gérôme". lamontagne.fr. 18 January 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Bertrand Tillier. Gérôme et la vérité en peinture, Autour de La Vérité sortant du puits.... Regarder Gérôme, Musée d'Orsay, Dec 2010, Paris, France.

- ^ Bayard, Émile; preface by Jean Léon Gérôme. Le Nu Esthétique. Paris: Bernard, 1902.

- ^ "La vérité est au musée". officiel-galeries-musees.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Gérôme (1903), p. 5.

- ^ Moreau-Vauthier, Charles; Gérôme, Jean Léon (1906). Gérôme: peintre et sculpteur (in French). Hachette. p. 287.

- ^ Benezit Dictionary of Artists 2006

- ^ Weinberg, H. Barbara, The American Pupils of Jean-Léon Gérôme, Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum, 1984

- ^ Neff, Emily Ballew. The Modern West: American Landscapes, 1890-1950, Yale University Press, 2006, p. 108.

- ^ Ackerman, Gerald M. Jean-Léon Gérôme: Monographie révisée et catalogue raisonné mis à jour, France: Art Création Réalisation, 2018.

- ^ Osborne, Carol M. Museum Builders in the West: The Stanfords as Collectors and Patrons of Art, 1870-1906. Stanford University Museum of Art, 1986, p. 18.

- ^ Morton, Mary G. "Gérôme in the Gilded Age," in The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904). Getty Museum and Musée d'Orsay, 2010, pp. 183–210.

- ^ Garvey, Dana M. (2013). "Edwin Lord Weeks: An American Artist in North Africa and South Asia" (PDF). digital.lib.washington.edu.

- ^ See critiques in Nochlin (1983); Toledano (1998, 4–6); Lees (2012).

- ^ a b Allan 2010, pp. 5–6

- ^ a b Turque, Bill (21 February 2013). "Once-reviled Orientalist art inspires Egyptian magnate to improve East-West relations". www.washingtonpost.com.

- ^ Weisberg, Gabriel P. "Exhibition review of The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide vol. 9, no. 2 (Autumn 2010)". Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ Finkel, Jori (13 June 2010). "Jean-Léon Gérôme's 'The Snake Charmer': A Twisted History". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Femme circassienne voilée". christies.com. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "Jean-Léon Gérôme page at Sotheby's". sothebys.com. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ For a recent appreciation see Sebastian Smee, "A masterpiece with a complicated afterlife", Washington Post, 30 Dec. 2020.

- ^ Weeks, Emily M. "Catalogue Note, Lot 670: Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Story of Anacreon (Four Works)". www.sothebys.com.

Sources

- Ackerman, Gerald (1986). The life and work of Jean-Léon Gérôme; catalogue raisonné. Sotheby's Publications. ISBN 0-85667-311-0.

- Ackerman, Gerald (2000). Jean-Léon Gérôme. Monographie révisée, catalogie raisonné mis a jour. ACR. ISBN 2-86770-137-6.

- Allan, Scott (2010). "Introduction". In Allan, Scott; Morton, Mary (eds.). Reconsidering Gérôme. Los Angeles: ISBN 978-1-60606-038-4.

- Bayard, Émile; preface by Jean Léon Gérôme. Le Nu Esthétique. Paris: Bernard, 1902.

- Beeny, Emily (2010). "Blood Spectacle: Gérôme in the Arena". In Allan, Scott; Morton, Mary (eds.). Reconsidering Gérôme. Los Angeles: ISBN 978-1-60606-038-4.

- Benezit E. - Dictionnaire des Peintres, Sculpteurs, Dessinateurs et Graveurs - ISBN 2-7000-0156-7(in French)

- Laurence des Cars, Dominque de Font-Rélaux and Édouard Papet (ed.), The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), Getty Museum and Musée d'Orsay, 2010.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. "Gérôme, Jean Léon," Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University, 1901.

- Garvey, Dana M. Edwin Lord Weeks: An American Artist in North Africa and South Asia, dissertation, University of Washington, 2013.

- Gérôme, Jean-Léon (1903). Preface to Charles Jalabert: l'homme, l'artiste, d'après sa correspondance by Émile Reinaud. Paris: Hachette, 1903, pp. 5–7.

- Hering, Fanny Field; introduction by Augustus St. Gaudens. Gérôme: The Life and Works of Jean-Léon Gérôme.New York, Cassell Publishing Company, 1892.

- Lees, Sarah. 2012. "Jean-Léon Gérôme: Slave Market". In Nineteenth-century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, edited by S. Lees. 359–363. Williamstown, Mass: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.

- Mitchell, Claudine (2010). "The Damaged Mirror: Gérôme's Narrative Technique and the Fractures of French History". In Allan, Scott; Morton, Mary (eds.). Reconsidering Gérôme. Los Angeles: ISBN 978-1-60606-038-4.

- Moreau-Vauthier, Charles. Gérôme: peintre et sculpteur (in French). Hachette, 1906.

- Nochlin, Linda. 1983. "The Imaginary Orient". Art in America 71(5): 118–31, 187–91.

- O'Sullivan N. Aloysius O'Kelly: Art, Nation, Empire, Field Day Publications, 2010.

- Scott C. Allan and Mary Morton (ed.), Reconsidering Gérôme, Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010, in: Art Bulletin 94 (2012), No. 2, pp. 312–316

- Toledano, Ehud R. 1998. Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle East. Seattle/London: University of Washington Press.

- Turner, J. – ISBN 0-19-517068-7

- Catalogue of the exhibition in the Musée de Vésoul (August 1981). Jean-Léon Gérôme : peintre, sculpteur et graveur; ses oeuvres conservées dans les collections françaises et privées. Ville de Vésoul.

External links

![]() Media related to Jean-Léon Gérôme at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jean-Léon Gérôme at Wikimedia Commons

- Eight portraits of Gérôme at various ages at the Bibliothèque Municipale de Besançon

- Musée Georges-Garret de Vesoul The museum in Gérôme's hometown displays many of his paintings and sculptures

- Jean-Léon Gérôme-Biography and Legacy at www.theartstory.org

- Fin de partie: A Group of Self-Portraits by Jean-Léon Gérôme by Susan Waller

- La Vérité est au musée—press kit for the 2012 exhibit at the Musée Anne-de-Beaujeu (in French)

- Jean-Léon Gérôme/Art Renewal Center Over 350 Gerome images, list of students with examples of work, biography, and letters

- Artencyclopedia.com page on Gérôme

- www.jeanleongerome.org nearly 300 images by the artist

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1906.

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Jean-Léon Gérôme in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

![Buying a Slave, 1857; provenance discussed by Sarah Lees[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d8/G%C3%A9r%C3%B4me%2C_Achat_d%27une_esclave%2C_1857_%285613508015%29.jpg/131px-G%C3%A9r%C3%B4me%2C_Achat_d%27une_esclave%2C_1857_%285613508015%29.jpg)

![Bashi-Bazouk, 1869, Metropolitan Museum of Art[49]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b5/G%C3%A9r%C3%B4me-Black_Bashi-Bazouk-c._1869.jpg/161px-G%C3%A9r%C3%B4me-Black_Bashi-Bazouk-c._1869.jpg)

![The Story of Anacreon 1: Cupid at the Door in a Rainstorm, c. 1899, private collection[50]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/84/Jean-L%C3%A9on_G%C3%A9r%C3%B4me%2C_The_Story_of_Anacreon_1--Cupid_at_the_Door_in_a_Rainstorm%2C_c_1899.jpg/200px-Jean-L%C3%A9on_G%C3%A9r%C3%B4me%2C_The_Story_of_Anacreon_1--Cupid_at_the_Door_in_a_Rainstorm%2C_c_1899.jpg)