Metformin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /mɛtˈfɔːrmɪn/, met-FOR-min |

| Trade names | Fortamet, Glucophage, Glumetza, others |

| Other names | N,N-dimethylbiguanide[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a696005 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50–60%[9][10] |

| Protein binding | Minimal[9] |

| Metabolism | Not by liver[9] |

| Elimination half-life | 4–8.7 hours[9] |

| Excretion | Urine (90%)[9] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.3±0.1[11] g/cm3 |

| |

| |

Metformin, sold under the brand name Glucophage, among others, is the main

Metformin is generally well tolerated.

Metformin is a biguanide anti-hyperglycemic agent.[14] It works by decreasing glucose production in the liver, increasing the insulin sensitivity of body tissues,[14] and increasing GDF15 secretion, which reduces appetite and caloric intake.[21][22][23][24]

Metformin was first described in scientific literature in 1922 by Emil Werner and James Bell.

Medical uses

Metformin is used to lower the blood glucose in those with type 2 diabetes.[14] It is also used as a second-line agent for infertility in those with polycystic ovary syndrome.[14][30]

Type 2 diabetes

The American Diabetes Association and the American College of Physicians both recommend metformin as a first-line agent to treat type 2 diabetes.[31][32][33] It is as effective as repaglinide and more effective than all other oral drugs for type 2 diabetes.[34]

Efficacy

Treatment guidelines for major professional associations, including the

The use of metformin reduces body weight in people with type 2 diabetes

In individuals with prediabetes, a 2019 systematic review comparing the effects of metformin with other interventions in the reduction of risk of developing type 2 diabetes[44] found moderate-quality evidence that metformin reduced the risk of developing type 2 diabetes when compared to diet and exercise or a placebo.[44] However, when comparing metformin to intensive diet or exercise, moderate-quality evidence was found that metformin did not reduce risk of developing type 2 diabetes and very low-quality evidence was found that adding metformin to intensive diet or exercise did not show any advantage or disadvantage in reducing risk of type 2 diabetes when compared to intensive exercise and diet alone.[44] The same review also found one suitable trial comparing the effects of metformin and sulfonylurea in reducing risk of developing type 2 diabetes in prediabetic individuals, however this trial did not report any patient relevant outcomes.[44]

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

In those with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), tentative evidence shows that metformin use increases the rate of live births.

The United Kingdom's

Gastric Cancer

Gastric cancer (GC) stands as a major global health concern due to its high prevalence and mortality rate. Amidst various treatment avenues, metformin, a common medication for type-2

Diabetes and pregnancy

A total review of metformin use during pregnancy compared to

Weight change

Metformin use is typically associated with weight loss.[65] It appears to be safe and effective in counteracting the weight gain caused by the antipsychotic medications olanzapine and clozapine.[66][67] Although modest reversal of clozapine-associated weight gain is found with metformin, primary prevention of weight gain is more valuable.[68]

Use with insulin

Metformin may reduce the insulin requirement in type 1 diabetes, albeit with an increased risk of hypoglycemia.[69]

Life extension

There is some evidence metformin may be helpful in extending lifespan, even in otherwise healthy people. It has received substantial interest as an agent that delays aging, possibly through similar mechanisms as its treatment of diabetes (insulin and carbohydrate regulation).[70][71]

Alzheimer's disease

Preliminary studies have examined whether metformin can reduce the risk of Alzheimer's disease, and whether there is a correlation between type 2 diabetes and risk of Alzheimer's disease.[72][73]

Contraindications

Metformin is contraindicated in people with:

- Severe renal impairment (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2)[74]

- Known hypersensitivity to metformin[74]

- Acute or chronic metabolic acidosis, including diabetic ketoacidosis (from uncontrolled diabetes),[74] with or without coma[75]

Adverse effects

The most common adverse effect of metformin is gastrointestinal irritation, including diarrhea, cramps, nausea, vomiting, and increased flatulence. Metformin is more commonly associated with gastrointestinal adverse effects than most other antidiabetic medications.[41] The most serious potential adverse effect of metformin is lactic acidosis; this complication is rare, and seems to be related to impaired liver or kidney function.[76] Metformin is not approved for use in those with severe kidney disease, but may still be used at lower doses in those with kidney problems.[77]

Gastrointestinal

Gastrointestinal upset can cause severe discomfort; it is most common when metformin is first administered, or when the dose is increased.[75] The discomfort can often be avoided by beginning at a low dose (1.0 to 1.7 g/day) and increasing the dose gradually, but even with low doses, 5% of people may be unable to tolerate metformin.[75][78] Use of slow or extended-release preparations may improve tolerability.[78]

Long-term use of metformin has been associated with increased homocysteine levels[79] and malabsorption of vitamin B12.[75][80][81] Higher doses and prolonged use are associated with increased incidence of vitamin B12 deficiency,[82] and some researchers recommend screening or prevention strategies.[83]

Lactic acidosis

Lactic acidosis almost never occurs with metformin exposure during routine medical care.[84] Rates of metformin-associated lactic acidosis are about nine per 100,000 persons/year, which is similar to the background rate of lactic acidosis in the general population.[85] A systematic review concluded no data exists to definitively link metformin to lactic acidosis.[86]

Metformin is generally safe in people with mild to moderate chronic kidney disease, with proportional reduction of metformin dose according to severity of

Metformin-associated lactate production may also take place in the large intestine, which could potentially contribute to lactic acidosis in those with risk factors.[90] The clinical significance of this is unknown, though, and the risk of metformin-associated lactic acidosis is most commonly attributed to decreased hepatic uptake rather than increased intestinal production.[40][89][91]

Overdose

The most common symptoms following an overdose include vomiting,

Metformin may be quantified in blood, plasma, or serum to monitor therapy, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning, or to assist in a forensic death investigation. Blood or plasma metformin concentrations are usually in a range of 1–4 mg/L in persons receiving therapeutic doses, 40–120 mg/L in victims of acute overdosage, and 80–200 mg/L in fatalities. Chromatographic techniques are commonly employed.[95][96]

The risk of metformin-associated lactic acidosis is also increased by a massive overdose of metformin, although even quite large doses are often not fatal.[97]

Interactions

The

Metformin also interacts with anticholinergic medications, due to their effect on gastric motility. Anticholinergic drugs reduce gastric motility, prolonging the time drugs spend in the gastrointestinal tract. This impairment may lead to more metformin being absorbed than without the presence of an anticholinergic drug, thereby increasing the concentration of metformin in the plasma and increasing the risk for adverse effects.[100]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

The molecular mechanism of metformin is not completely understood. Multiple potential mechanisms of action have been proposed: inhibition of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (

Metformin exerts an anorexiant effect in most people, decreasing caloric intake.

Activation of AMPK was required for metformin's inhibitory effect on liver glucose production.[106] AMPK is an enzyme that plays an important role in insulin signaling, whole-body energy balance, and the metabolism of glucose and fats.[107] AMPK activation is required for an increase in the expression of small heterodimer partner, which in turn inhibited the expression of the hepatic gluconeogenic genes phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucose 6-phosphatase.[108] Metformin is frequently used in research along with AICA ribonucleotide as an AMPK agonist. The mechanism by which biguanides increase the activity of AMPK remains uncertain: metformin increases the concentration of cytosolic adenosine monophosphate (AMP) (as opposed to a change in total AMP or total AMP/adenosine triphosphate) which could activate AMPK allosterically at high levels;[109] a newer theory involves binding to PEN-2.[110] Metformin inhibits cyclic AMP production, blocking the action of glucagon, and thereby reducing fasting glucose levels.[111] Metformin also induces a profound shift in the faecal microbial community profile in diabetic mice, and this may contribute to its mode of action possibly through an effect on glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion.[102]

In addition to suppressing hepatic glucose production, metformin increases insulin sensitivity, enhances peripheral glucose uptake (by inducing the phosphorylation of GLUT4 enhancer factor), decreases insulin-induced suppression of fatty acid oxidation,[112] and decreases the absorption of glucose from the gastrointestinal tract. Increased peripheral use of glucose may be due to improved insulin binding to insulin receptors.[113] The increase in insulin binding after metformin treatment has also been demonstrated in patients with type 2 diabetes.[114]

AMPK probably also plays a role in increased peripheral insulin sensitivity, as metformin administration increases AMPK activity in skeletal muscle.[115] AMPK is known to cause GLUT4 deployment to the plasma membrane, resulting in insulin-independent glucose uptake.[116] Some metabolic actions of metformin do appear to occur by AMPK-independent mechanisms, however AMPK likely has a modest overall effect and its activity is not likely to directly decrease gluconeogenesis in the liver.[117]

Metformin has indirect

Metformin also has significant effects on the gut microbiome, such as its effect on increasing agmatine production by gut bacteria, but the relative importance of this mechanism compared to other mechanisms is uncertain.[120][121][122]

Due to its effect on GLUT4 and AMPK, metformin has been described as an exercise mimetic.[123][124]

Pharmacokinetics

Metformin has an oral bioavailability of 50–60% under fasting conditions, and is absorbed slowly.[8][125] Peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) are reached within 1–3 hours of taking immediate-release metformin and 4–8 hours with extended-release formulations.[8][125] The plasma protein binding of metformin is negligible, as reflected by its very high apparent volume of distribution (300–1000 L after a single dose). Steady state is usually reached in 1–2 days.[8]

Metformin has acid dissociation constant values (pKa) of 2.8 and 11.5, so it exists very largely as the hydrophilic cationic species at physiological pH values. The metformin pKa values make it a stronger base than most other basic medications with less than 0.01% nonionized in blood. Furthermore, the lipid solubility of the nonionized species is slight as shown by its low logP value (log(10) of the distribution coefficient of the nonionized form between octanol and water) of −1.43. These chemical parameters indicate low lipophilicity and, consequently, rapid passive diffusion of metformin through cell membranes is unlikely. As a result of its low lipid solubility it requires the transporter SLC22A1 in order for it to enter cells.[126][127] The logP of metformin is less than that of phenformin (−0.84) because two methyl substituents on metformin impart lesser lipophilicity than the larger phenylethyl side chain in phenformin. More lipophilic derivatives of metformin are presently under investigation with the aim of producing prodrugs with superior oral absorption than metformin.[128]

Metformin is not

Some evidence indicates that liver concentrations of metformin in humans may be two to three times higher than plasma concentrations, due to portal vein absorption and first-pass uptake by the liver in oral administration.[117]

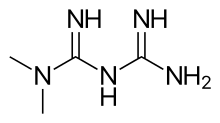

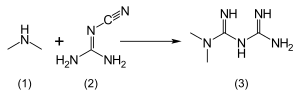

Chemistry

Metformin hydrochloride (1,1-dimethylbiguanide hydrochloride) is freely soluble in water, slightly soluble in ethanol, but almost insoluble in acetone, ether, or chloroform. The pKa of metformin is 12.4.

According to the procedure described in the 1975 Aron patent,

Derivatives

A new derivative HL156A, also known as IM156, is a potential new drug for medical use.[135][136][137][138][139][140]

History

The

Metformin was first described in the scientific literature in 1922, by Emil Werner and James Bell, as a product in the synthesis of N,N-dimethylguanidine.[131] In 1929, Slotta and Tschesche discovered its sugar-lowering action in rabbits, finding it the most potent biguanide analog they studied.[142] This result was ignored, as other guanidine analogs such as the synthalins, took over and were themselves soon overshadowed by insulin.[143]

Interest in metformin resumed at the end of the 1940s. In 1950, metformin, unlike some other similar compounds, was found not to decrease

French diabetologist Jean Sterne studied the antihyperglycemic properties of galegine, an alkaloid isolated from G. officinalis, which is related in structure to metformin, and had seen brief use as an antidiabetic before the synthalins were developed.[150] Later, working at Laboratoires Aron in Paris, he was prompted by Garcia's report to reinvestigate the blood sugar-lowering activity of metformin and several biguanide analogs. Sterne was the first to try metformin on humans for the treatment of diabetes; he coined the name "Glucophage" (glucose eater) for the medication and published his results in 1957.[143][150]

Metformin became available in the British National Formulary in 1958. It was sold in the UK by a small Aron subsidiary called Rona.[151]

Broad interest in metformin was not rekindled until the withdrawal of the other biguanides in the 1970s.

Society and culture

Environmental

Metformin and its major transformation product guanylurea are present in

Formulations

The name "Metformin" is the

Combination with other medications

When used for type 2 diabetes, metformin is often prescribed in combination with other medications.

Several are available as

Thiazolidinediones (glitazones)

Rosiglitazone

A combination of metformin and

Formulations are 500/1, 500/2, 500/4, 1000/2, and 1000 mg/4 mg of metformin/rosiglitazone.By 2009, it had become the most popular metformin combination.[162]

In 2005, the stock of Avandamet was removed from the market, after inspections showed the factory where it was produced was violating

However, following a meta-analysis in 2007 that linked the medication's use to an increased risk of heart attack,[165] concerns were raised over the safety of medicines containing rosiglitazone. In September 2010, the European Medicines Agency recommended that the medication be suspended from the European market because the benefits of rosiglitazone no longer outweighed the risks.[166][167]

It was withdrawn from the market in the UK and India in 2010,[168] and in New Zealand and South Africa in 2011.[169] From November 2011 until November 2013 the FDA[170] did not allow rosiglitazone or metformin/rosiglitazone to be sold without a prescription; moreover, makers were required to notify patients of the risks associated with its use, and the drug had to be purchased by mail order through specified pharmacies.[171][172]

In November 2013, the FDA lifted its earlier restrictions on rosiglitazone after reviewing the results of the 2009 RECORD clinical trial (a six-year, open-label

Pioglitazone

The combination of metformin and pioglitazone (Actoplus Met, Piomet, Politor, Glubrava) is available in the US and the European Union.[176][177][178][179][180]

DPP-4 inhibitors

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors inhibit dipeptidyl peptidase-4 and thus reduce glucagon and blood glucose levels.

DPP-4 inhibitors combined with metformin include a

SGLT-2 inhibitors

There are combinations of metformin with the

.Sulfonylureas

Sulfonylureas act by increasing insulin release from the beta cells in the pancreas.[191]

A 2019 systematic review suggested that there is limited evidence if the combined used of metformin with sulfonylurea compared to the combination of metformin plus another glucose-lowering intervention, provides benefit or harm in mortality, severe adverse events, macrovascular and microvascular complications.[192] Combined metformin and sulfonylurea therapy did appear to lead to higher risk of hypoglicaemia.[192]

Metformin is available combined with the sulfonylureas glipizide (Metaglip) and glibenclamide (US: glyburide) (Glucovance). Generic formulations of metformin/glipizide and metformin/glibenclamide are available (the latter is more popular).[193]

Meglitinide

Meglitinides are similar to sulfonylureas, as they bind to beta cells in the pancreas, but differ by the site of binding to the intended receptor and the drugs' affinities to the receptor.[191] As a result, they have a shorter duration of action compared to sulfonylureas, and require higher blood glucose levels to begin to secrete insulin. Both meglitinides, known as nateglinide and repanglinide, is sold in formulations combined with metformin. A repaglinide/metformin combination is sold as Prandimet, or as its generic equivalent.[194][195]

Triple combination

The combination of metformin with dapagliflozen and saxagliptin is available in the United States as Qternmet XR.[196][197]

The combination of metformin with pioglitazone and glibenclamide[198] is available in India as Accuglim-MP, Adglim MP, and Alnamet-GP, along with the Philippines as Tri-Senza.[157]

The combination of metformin with pioglitazone and lipoic acid is available in Turkey as Pional.[157]

Impurities

In December 2019, the US FDA announced that it learned that some metformin medicines manufactured outside the United States might contain a nitrosamine impurity called

In February 2020, the FDA found NDMA levels in some tested metformin samples that did not exceed the acceptable daily intake.[201][202]

In February 2020, Health Canada announced a recall of Apotex immediate-release metformin,[203] followed in March by recalls of Ranbaxy metformin[204] and in March by Jamp metformin.[205]

In May 2020, the FDA asked five companies to voluntarily recall their

In June 2020, the FDA posted its laboratory results showing NDMA amounts in metformin products it tested.[213] It found NDMA in certain lots of ER metformin, and is recommending companies recall lots with levels of NDMA above the acceptable intake limit of 96 nanograms per day.[213] The FDA is also collaborating with international regulators to share testing results for metformin.[213]

In July 2020, Lupin Pharmaceuticals pulled all lots (batches) of metformin after discovering unacceptably high levels of NDMA in tested samples.[214]

In August 2020, Bayshore Pharmaceuticals recalled two lots of tablets.[215]

Research

Metformin has been studied for its effects on multiple other conditions, including:

- Cardiovascular disease in people with diabetes[224]

- Aging[225][70]

While metformin may reduce body weight in persons with

There is also some research suggesting that although metformin prevents diabetes, it does not reduce the risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease and thus does not extend lifespan in non-diabetic individuals.[228] Furthermore, some studies suggest that long-term chronic use of metformin by healthy individuals may develop vitamin B12 deficiency.[229]

References

- S2CID 24531910.

- ^ "Metformin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 10 September 2019. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Metformin SANDOZ metformin hydrochloride 850mg tablet bottle (148270)". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 27 May 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ PMID 6847752.

- ^ "Metformin Hydrochloride". Health Canada. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ "Glucophage 500 mg film coated tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 25 October 2022. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Glucophage (metformin hydrochloride) tablets, for oral use; Glucophage XR (metformin hydrochloride) extended-release tablets, for oral use Initial U.S. Approval:1995". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ PMID 7601013.

- PMID 12930161.

- ^ "Metformin". www.chemsrc.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- S2CID 245538347.

- ^ PMID 31497854.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Metformin Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- S2CID 32016657.

- PMID 27716110.

- PMID 25954799.

- ^ S2CID 312517.

- PMID 31907741.

- PMID 21617112.

- ^ PMID 31875646.

- S2CID 213199603.

- ^ S2CID 10289148.

- ^ PMID 35238637.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-527-63212-1. Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-323-02964-3. Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Metformin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ PMID 14576245.

- PMID 21403054.

- ^ PMID 22517736.

- PMID 22312141.

- PMID 30230172.

- PMID 24800783.

- PMID 32501595.

- ^ PMID 10333900.

- PMID 17653063.

- PMID 27899001.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-162444-2.

- ^ PMID 17638715.

- ISBN 978-0-07-141613-9.

- ^ "Glucophage package insert". Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. 2009. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021 – via DailyMed.

- ^ PMID 31794067.

- ^ PMID 29183107.

Our updated review suggests that metformin alone may be beneficial over placebo for live birth, although the evidence quality was low.

- S2CID 41145972.

- PMID 23162354.

- PMID 29846959.

- ^ PMID 33347618.

- PMID 30039871.

- ISBN 978-1-900364-97-3. Archived(PDF) from the original on 11 July 2009.

- ^ Balen A (December 2008). "Metformin therapy for the management of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome" (PDF). Scientific Advisory Committee Opinion Paper 13. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2009. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- PMID 18308833.

- ^ S2CID 44203632.

- PMID 19841045.

- PMID 32982447.

- ^ Sharma A (29 October 2023). "The Role of Metformin in Gastric Cancer Treatment". Witfire. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- S2CID 3418227.

- S2CID 28115952.

- PMID 26117686.

- ^ PMID 25609400.

- from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- PMID 25013215.

- PMID 31386659.

- PMID 30874963.

- PMID 25664341.

- PMID 21284696.

- PMID 27304831.

- PMID 20057994.

- ^ PMID 26931809.

- PMID 32333835.

- PMID 30149446.

- PMID 28800055.

- ^ a b c "Metformin: medicine to treat type 2 diabetes". National Health Service. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d "METFORMIN HYDROCHLORIDE". NICE. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- S2CID 9746741.

- PMID 24711640.

- ^ S2CID 9277684.

- S2CID 12507226.

- PMID 12390080.

- PMID 11863489.

- PMID 20488910.

- PMID 17030830.

- PMID 18941734.

- PMID 10372243.

- PMID 14638559.

- PMID 25536258.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises warnings regarding use of the diabetes medicine metformin in certain patients with reduced kidney function". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 14 November 2017. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-4678-6.

- ^ S2CID 9140541.

- ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2.

- S2CID 5413561.

- PMID 19561734.

- ^ S2CID 13861731.

- PMID 19783231.

- ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 939–940.

- S2CID 45218798.

- PMID 3593625.

- S2CID 26919498.

- PMID 27092232.

- PMID 23835523.

- ^ S2CID 42142919.

- PMID 24847880.

- PMID 30205369.

- PMID 11118008.

- PMID 11602624.

- PMID 17307971.

- PMID 17909097.

- PMID 17369473.

- PMID 35197629.

- PMID 23292513.

- PMID 16478780.

- PMID 8569826.

- PMID 3745404.

- PMID 12086935.

- PMID 22436748.

- ^ PMID 32897388.

- ^ S2CID 149443722.

- PMID 29293982.

- PMID 32409589.

- S2CID 204836737.

- S2CID 219607625.

- PMID 29765854.

- PMID 21602430.

- ^ a b Heller JB (2007). "Metformin overdose in dogs and cats" (PDF). Veterinary Medicine (April): 231–33. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2007.

- PMID 24462823.

- ^ PMID 26475449.

- S2CID 1440441.

- ^ PMID 12909816.

- ISBN 978-0471266945.

- ^ from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- .

- ^ "Procédé de préparation de chlorhydrate de diméthylbiguanide". Patent FR 2322860 (in French). 1975.

- ISBN 978-0-8155-1526-5.

- PMID 29285837.

- PMID 30161162.

- PMID 32872293.

- PMID 30222592.

- PMID 27582539.

- PMID 26661649.

- ^ PMID 11602616.

- .

- ^ .

- PMID 15405470.

- ^ About Eusebio Y. Garcia, see: Carteciano J (2005). "Search for DOST-NRCP Dr. Eusebio Y. Garcia Award". Philippines Department of Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 24 October 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- PMID 14779282.

- PMID 16766803. Archived from the original(PDF) on 24 October 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- PMID 13269290.

- ^ Quoted from Chemical Abstracts, v.49, 74699 (1955) Supniewski J, Krupinska J (1954). "[Effect of biguanide derivatives on experimental cowpox in rabbits]". Bulletin de l'Académie Polonaise des Sciences, Classe 3: Mathématique, Astronomie, Physique, Chimie, Géologie et Géographie (in French). 2(Classe II): 161–65.

- ^ S2CID 208203689. Archived from the originalon 17 December 2012.

- (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ "FDA Approves New Diabetes Drug" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 30 December 1994. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Glucophage (metformin)" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

- PMID 30350841.

- ^ PMID 31371854.

- ^ PMID 23810664.

Metformin use at time of RP was extracted from the Mayo Clinic electronic medical record (EMR) by searching in the 3 months prior to the RP for the terms- metformin, Glucophage, Glumetza, Riomet, Fortamet, Obimet, Gluformin, Dianben, Diabex, Diaformin or Metsol.

- ^ a b c "Metformin". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- S2CID 6569131.

- PMID 15931309.

- GlaxoSmithKline. 12 October 2002. Archivedfrom the original on 21 January 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "2009 Top 200 branded drugs by total prescriptions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2011. (96.5 KB). Drug Topics (17 June 2010). Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ "Questions and Answers about the Seizure of Paxil CR and Avandamet" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 4 March 2005. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- ^ "Teva Pharm announces settlement of generic Avandia, Avandamet, and Avandaryl litigation with GlaxoSmithKline" (Press release). Reuters. 27 September 2007. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- PMID 17517853.

- ^ "European Medicines Agency recommends suspension of Avandia, Avandamet and Avaglim". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 23 September 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ "Call to 'suspend' diabetes drug". BBC News Online. 23 September 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2010.

- ^ "Drugs banned in India". Central Drugs Standard Control Organization, Dte.GHS, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- NZPA. 17 February 2011. Archived from the originalon 13 October 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Harris G (19 February 2010). "Controversial Diabetes Drug Harms Heart, U.S. Concludes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017.

- ^ "Updated Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 July 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA requires removal of some prescribing and dispensing restrictions for rosiglitazone-containing diabetes medicines". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 21 June 2019. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ "Glaxo's Avandia Cleared From Sales Restrictions by FDA". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014.

- ^ "FDA requires removal of certain restrictions on the diabetes drug Avandia". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 25 November 2013. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015.

- ^ "US agency reverses stance on controversial diabetes drug". Archived from the original on 11 December 2015.

- ^ "Glubrava EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "Competact EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "Pioglitazone (marketed as Actos, Actoplus Met, Duetact, and Oseni) Information". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 11 January 2017. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises warnings regarding use of the diabetes medicine metformin in certain patients with reduced kidney function". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 April 2013. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Updated FDA review concludes that use of type 2 diabetes medicine pioglitazone may be linked to an increased risk of bladder cancer". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 4 August 2011. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "Janumet- sitagliptin and metformin hydrochloride tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 12 August 2019. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "Janumet EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "Kombiglyze XR- saxagliptin and metformin hydrochloride tablet, film coated, extended release". DailyMed. 24 October 2019. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "Komboglyze EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "Kazano- alogliptin and metformin hydrochloride tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 14 June 2019. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "Vipdomet EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "Jentadueto EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "Jentadueto- linagliptin and metformin hydrochloride tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 18 July 2019. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "Jentadueto XR- linagliptin and metformin hydrochloride tablet, film coated, extended release". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ "Linagliptin and Metformin Hydrochloride: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ PMID 27621259.

- ^ PMID 30998259.

- ^ "The Use of Medicines in the United States: Review of 2010" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 April 2011. (1.79 MB). IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics (April 2011). Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: PrandiMet (repaglinide/metformin HCI fixed-dose combination) NDA 22386". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Qternmet XR (dapagliflozin, saxagliptin, and metformin hydrochloride) extended-release tablets, for oral use Initial U.S. Approval: 2019". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- S2CID 22085315.

- ^ "Statement from Janet Woodcock, M.D., director of FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, on impurities found in diabetes drugs outside the U.S." U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 5 December 2019. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Recalls and safety alerts". Health Canada evaluating NDMA in metformin drugs. 5 December 2019. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "Laboratory Tests - Metformin". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 February 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "FDA Updates and Press Announcements on NDMA in Metformin". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 4 February 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "APO-Metformin (2020-02-04)". Health Canada. 4 February 2020. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Ranbaxy Metformin Product Recall (2020-02-26)". Health Canada. 26 February 2020. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Jamp-Metformin Product Recall (2020-03-10)". Health Canada. 10 March 2020. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "FDA Alerts Patients and Health Care Professionals to Nitrosamine Impurity Findings in Certain Metformin Extended-Release Products" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 May 2020. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Questions and Answers: NDMA impurities in metformin products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 May 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ "Amneal Pharmaceuticals LLC Issues Voluntary Nationwide Recall of Metformin Hydrochloride Extended Release Tablets, USP, 500 mg and 750 mg, Due to Detection of N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) Impurity". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 May 2020. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Apotex Corp. Issues Voluntary Nationwide Recall of Metformin Hydrochloride Extended-Release Tablets 500mg Due to the Detection of N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 27 May 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. Initiates Voluntary Nationwide Recall of Metformin Hydrochloride Extended-Release Tablets USP 500 mg and 750 mg Due to Detection of N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2 June 2020. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ "Marksans Pharma Limited Issues Voluntary Nationwide Recall of Metformin Hydrochloride Extended-Release Tablets, USP 500mg, Due to the Detection of N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2 June 2020. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ Cavazzoni P (28 May 2020). "Re: Docket No. FDA-2020-P-0978" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Laboratory Tests - Metformin". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 5 June 2020. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Lupin Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Issues Voluntarily Nationwide Recall of Metformin Hydrochloride Extended-Release Tablets, 500mg and 1000mg Due to the Detection of N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) Impurity" (Press release). Lupin Pharmaceuticals Inc. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2020 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ "Bayshore Pharmaceuticals, LLC Issues Voluntary Nationwide Recall of Metformin Hydrochloride Extended-Release Tablets USP, 500 mg and 750 mg Due to the Detection of N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) Impurity". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 19 August 2020. Archived from the original on 19 December 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- S2CID 215741792.

- PMID 31783920.

- PMID 30122876.

- PMID 16684823.

- PMID 21632811.

- S2CID 9129907.

- PMID 20442309.

- PMID 24224094.

- ^ S2CID 20334490.

- PMID 31405774.

- from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- PMID 27304507.

- ^ Lee CG, Heckman-Stoddard B, Dabelea D, et al. Effect of Metformin and Lifestyle Interventions on Mortality in the Diabetes Prevention Program and Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(12):2775-2782. doi:10.2337/dc21-1046

- PMID 34421827.

Further reading

- Markowicz-Piasecka M, Huttunen KM, Mateusiak L, Mikiciuk-Olasik E, Sikora J (2017). "Is Metformin a Perfect Drug? Updates in Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 23 (17): 2532–2550. PMID 27908266.

- McCreight LJ, Bailey CJ, Pearson ER (March 2016). "Metformin and the gastrointestinal tract". Diabetologia. 59 (3): 426–35. PMID 26780750.

- Moin T, Schmittdiel JA, Flory JH, Yeh J, Karter AJ, Kruge LE, et al. (October 2018). "Review of Metformin Use for Type 2 Diabetes Prevention". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 55 (4): 565–574. PMID 30126667.

- Rena G, Hardie DG, Pearson ER (September 2017). "The mechanisms of action of metformin". Diabetologia. 60 (9): 1577–1585. PMID 28776086.

- Sanchez-Rangel E, Inzucchi SE (September 2017). "Metformin: clinical use in type 2 diabetes". Diabetologia. 60 (9): 1586–1593. PMID 28770321.

- Zhou J, Massey S, Story D, Li L (September 2018). "Metformin: An Old Drug with New Applications". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 19 (10): 2863. PMID 30241400.

- Zhou T, Xu X, Du M, Zhao T, Wang J (October 2018). "A preclinical overview of metformin for the treatment of type 2 diabetes". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 106: 1227–1235. S2CID 52031602.

External links

- "Nitrosamine impurities in medications: Guidance". Health Canada. 4 April 2022.