Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham | |

|---|---|

Principle of utility Felicific calculus | |

| Signature | |

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Liberalism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

| Part of Radicalism |

Jeremy Bentham (

Bentham defined as the "fundamental

Bentham's students included his secretary and collaborator James Mill, the latter's son, John Stuart Mill, the legal philosopher John Austin and American writer and activist John Neal. He "had considerable influence on the reform of prisons, schools, poor laws, law courts, and Parliament itself."[16]

On his death in 1832, Bentham left instructions for his body to be first dissected, and then to be permanently preserved as an "auto-icon" (or self-image), which would be his memorial. This was done, and the auto-icon is now on public display in the entrance of the Student Centre at University College London (UCL). Because of his arguments in favour of the general availability of education, he has been described as the "spiritual founder" of UCL. However, he played only a limited direct part in its foundation.[17]

Biography

Early life

Bentham was born on 4 February

He attended Westminster School; in 1760, at age 12, his father sent him to The Queen's College, Oxford, where he completed his bachelor's degree in 1764, receiving the title of MA in 1767.[1] He trained as a lawyer and, though he never practised, was called to the bar in 1769. He became deeply frustrated with the complexity of English law, which he termed the "Demon of Chicane".[22] When the American colonies published their Declaration of Independence in July 1776, the British government did not issue any official response but instead secretly commissioned London lawyer and pamphleteer John Lind to publish a rebuttal.[23] His 130-page tract was distributed in the colonies and contained an essay titled "Short Review of the Declaration" written by Bentham, a friend of Lind, which attacked and mocked the Americans' political philosophy.[24][25]

Abortive prison project and the Panopticon

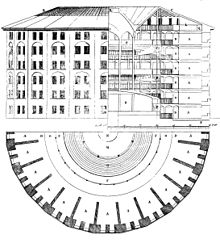

In 1786 and 1787, Bentham travelled to Krichev in White Russia (modern Belarus) to visit his brother, Samuel, who was engaged in managing various industrial and other projects for Prince Potemkin. It was Samuel (as Jeremy later repeatedly acknowledged) who conceived the basic idea of a circular building at the hub of a larger compound as a means of allowing a small number of managers to oversee the activities of a large and unskilled workforce.[26][27]

Bentham began to develop this model, particularly as applicable to prisons, and outlined his ideas in a series of letters sent home to his father in England.[28] He supplemented the supervisory principle with the idea of contract management; that is, an administration by contract as opposed to trust, where the director would have a pecuniary interest in lowering the average rate of mortality.[29]

The

The ultimately abortive proposal for a panopticon prison to be built in England was one among his many proposals for legal and social reform.[31] But Bentham spent some sixteen years of his life developing and refining his ideas for the building and hoped that the government would adopt the plan for a National Penitentiary appointing him as contractor-governor. Although the prison was never built, the concept had an important influence on later generations of thinkers. Twentieth-century French philosopher Michel Foucault argued that the panopticon was paradigmatic of several 19th-century "disciplinary" institutions.[32] Bentham remained bitter throughout his later life about the rejection of the panopticon scheme, convinced that it had been thwarted by the King and an aristocratic elite. Philip Schofield argues that it was largely because of his sense of injustice and frustration that he developed his ideas of "sinister interest"—that is, of the vested interests of the powerful conspiring against a wider public interest—which underpinned many of his broader arguments for reform.[33]

On his return to England from Russia, Bentham had commissioned drawings from an architect, Willey Reveley.[34] In 1791, he published the material he had written as a book, although he continued to refine his proposals for many years to come. He had by now decided that he wanted to see the prison built: when finished, it would be managed by himself as contractor-governor, with the assistance of Samuel. After unsuccessful attempts to interest the authorities in Ireland and revolutionary France,[35] he started trying to persuade the prime minister, William Pitt, to revive an earlier abandoned scheme for a National Penitentiary in England, this time to be built as a panopticon. He was eventually successful in winning over Pitt and his advisors, and in 1794 was paid £2,000 for preliminary work on the project.[36]

The intended site was one that had been authorised (under an

From his point of view, the site was far from ideal, being marshy, unhealthy, and too small. When he asked the government for more land and more money, however, the response was that he should build only a small-scale experimental prison—which he interpreted as meaning that there was little real commitment to the concept of the panopticon as a cornerstone of penal reform.

Nevertheless, a few years later the government revived the idea of a National Penitentiary, and in 1811 and 1812 returned specifically to the idea of a panopticon.

More successful was his cooperation with

Correspondence and contemporary influences

Bentham was in correspondence with many influential people. In the 1780s, for example, Bentham maintained a correspondence with the ageing

In 1821, John Cartwright proposed to Bentham that they serve as "Guardians of Constitutional Reform", seven "wise men" whose reports and observations would "concern the entire Democracy or Commons of the United Kingdom". Describing himself, among the names mentioned which also included Sir Francis Burdett, George Ensor, and Sir Matthew Wood, and as a "nonentity", Bentham declined the offer.[51]

South Australian colony proposal

On 3 August 1831 the Committee of the National Colonization Society approved the printing of its proposal to establish a free colony on the south coast of Australia, funded by the sale of appropriated colonial lands, overseen by a joint-stock company, and which would be granted powers of self-government as soon as was practicable. Contrary to assumptions, Bentham had no hand in the preparation of the 'Proposal to His Majesty's Government for founding a colony on the Southern Coast of Australia, which was prepared under the auspices of Robert Gouger, Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, and Anthony Bacon. Bentham did, however, in August 1831, draft an unpublished work entitled 'Colonization Company Proposal', which constitutes his commentary upon the National Colonization Society's 'Proposal'.[52]

Westminster Review

In 1823, he co-founded

Personal life

Bentham had several infatuations with women, and wrote on sex.[56] He never married.[57]

An insight into his character is given in Michael St. John Packe's The Life of John Stuart Mill:

During his youthful visits to Bowood House, the country seat of his patron Lord Lansdowne, he had passed his time at falling unsuccessfully in love with all the ladies of the house, whom he courted with a clumsy jocularity, while playing chess with them or giving them lessons on the harpsichord. Hopeful to the last, at the age of eighty he wrote again to one of them, recalling to her memory the far-off days when she had "presented him, in ceremony, with the flower in the green lane" [citing Bentham's memoirs]. To the end of his life he could not hear of Bowood without tears swimming in his eyes, and he was forced to exclaim, "Take me forward, I entreat you, to the future—do not let me go back to the past."[58]

A psychobiographical study by Philip Lucas and Anne Sheeran argues that he may have had Asperger's syndrome.[59]

Bentham's daily pattern was to rise at 6 am, walk for 2 hours or more, and then work until 4 pm.[60]

Legacy

The Faculty of Laws at University College London occupies Bentham House, next to the main UCL campus.[61]

Bentham's name was adopted by the Australian litigation funder IMF Limited to become Bentham IMF Limited on 28 November 2013, in recognition of Bentham being "among the first to support the utility of litigation funding".[62]

Work

Utilitarianism

| Part of a series on |

| Utilitarianism |

|---|

| Philosophy portal |

Bentham today is considered as the "Father of Utilitarianism".[63] His ambition in life was to create a "Pannomion", a complete utilitarian code of law. He not only proposed many legal and social reforms, but also expounded an underlying moral principle on which they should be based. This philosophy of utilitarianism took for its "fundamental axiom" to be the notion that it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong.[64] Bentham claimed to have borrowed this concept from the writings of Joseph Priestley,[65] although the closest that Priestley in fact came to expressing it was in the form "the good and happiness of the members, that is the majority of the members of any state, is the great standard by which every thing [sic] relating to that state must finally be determined."[66]

Bentham was a rare major figure in the history of philosophy to endorse psychological egoism.[67] He was also a determined opponent of religion, as Crimmins observes: "Between 1809 and 1823 Jeremy Bentham carried out an exhaustive examination of religion with the declared aim of extirpating religious beliefs, even the idea of religion itself, from the minds of men."[68]

Bentham also suggested a procedure for estimating the

Principle of utility

The principle of utility, or "

Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do. On the one hand the standard of right and wrong, on the other the chain of causes and effects, are fastened to their throne. They govern us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think.…

Bentham's Principles of Morals and Legislation focuses on the principle of utility and how this view of morality ties into legislative practices.[70] His principle of utility regards good as that which produces the greatest amount of pleasure and the minimum amount of pain and evil as that which produces the most pain without the pleasure. This concept of pleasure and pain is defined by Bentham as physical as well as spiritual. Bentham writes about this principle as it manifests itself within the legislation of a society.[70]

In order to measure the extent of pain or pleasure that a certain decision will create, he lays down a set of criteria divided into the categories of intensity, duration, certainty, proximity, productiveness, purity, and extent.[70] Using these measurements, he reviews the concept of punishment and when it should be used as far as whether a punishment will create more pleasure or more pain for a society.

He calls for legislators to determine whether punishment creates an even more evil offence. Instead of suppressing the evil acts, Bentham argues that certain unnecessary laws and punishments could ultimately lead to new and more dangerous vices than those being punished to begin with, and calls upon legislators to measure the pleasures and pains associated with any legislation and to form laws in order to create the greatest good for the greatest number. He argues that the concept of the individual pursuing his or her own happiness cannot be necessarily declared "right", because often these individual pursuits can lead to greater pain and less pleasure for a society as a whole. Therefore, the legislation of a society is vital to maintain the maximum pleasure and the minimum degree of pain for the greatest number of people.[citation needed]

Hedonistic/felicific calculus

In his exposition of the felicific calculus, Bentham proposed a classification of 12 pains and 14 pleasures, by which we might test the "happiness factor" of any action.[71] For Bentham, according to P. J. Kelly, the law "provides the basic framework of social interaction by delimiting spheres of personal inviolability within which individuals can form and pursue their own conceptions of well-being".[72] It provides security, a precondition for the formation of expectations. As the hedonic calculus shows "expectation utilities" to be much higher than natural ones, it follows that Bentham does not favour the sacrifice of a few to the benefit of the many. Law professor Alan Dershowitz has quoted Bentham to argue that torture should sometimes be permitted.[73]

Criticisms

Utilitarianism was revised and expanded by Bentham's student

Bentham's critics have claimed that he undermined the foundation of a free society by rejecting natural rights.[75] Historian Gertrude Himmelfarb wrote "The principle of the greatest happiness of the greatest number was as inimical to the idea of liberty as to the idea of rights."[76]

Bentham's "hedonistic" theory (a term from J. J. C. Smart) is often criticised for lacking a principle of fairness embodied in a conception of justice. In Bentham and the Common Law Tradition, Gerald J. Postema states: "No moral concept suffers more at Bentham's hand than the concept of justice. There is no sustained, mature analysis of the notion."[77] Thus, some critics[who?] object, it would be acceptable to torture one person if this would produce an amount of happiness in other people outweighing the unhappiness of the tortured individual. However, as P. J. Kelly argued in Utilitarianism and Distributive Justice: Jeremy Bentham and the Civil Law, Bentham had a theory of justice that prevented such consequences.[clarification needed]

Economics

| Part of a series on |

| Hedonism |

|---|