And did those feet in ancient time

| And did those feet in ancient time | |

|---|---|

| by William Blake | |

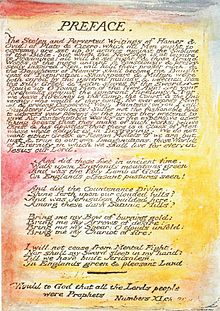

The preface to Milton, as it appeared in Blake's own illuminated version | |

| Written | 1804 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Form | Epic poetry |

| Publication date | 1808 |

| Lines | 16 |

| Full text | |

"And did those feet in ancient time" is a poem by

It is often assumed that the poem was inspired by the

In the most common interpretation of the poem, Blake asks whether a visit by Jesus briefly created heaven in England, in contrast to the "dark Satanic Mills" of the Industrial Revolution. Blake's poem asks four questions rather than asserting the historical truth of Christ's visit.[5][6] The second verse is interpreted as an exhortation to create an ideal society in England, whether or not there was a divine visit.[7][8]

Text

The original text is found in the preface Blake wrote for inclusion with Milton, a Poem, following the lines beginning "The Stolen and Perverted Writings of Homer & Ovid: of Plato & Cicero, which all Men ought to contemn: ..."[9]

Blake's poem

And did those feet in ancient time,

Walk upon Englands[b] mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God,

On Englands pleasant pastures seen!

And did the Countenance Divine,

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these[c] dark Satanic Mills?

Bring me my Bow of burning gold:

Bring me my Arrows of desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold:

Bring me my Chariot of fire!

I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In Englands green & pleasant Land.

Beneath the poem Blake inscribed a quotation from the Bible:[10]

"Dark Satanic Mills"

The phrase "dark Satanic Mills", which entered the English language from this poem, is often interpreted as referring to the early Industrial Revolution and its destruction of nature and human relationships.[11] That view has been linked to the fate of the Albion Flour Mills in Southwark, the first major factory in London. The rotary steam-powered flour mill, built by Matthew Boulton, assisted by James Watt, could produce 6,000 bushels of flour per week. The factory could have driven independent traditional millers out of business, but it was destroyed in 1791 by fire. There were rumours of arson, but the most likely cause was a bearing that overheated due to poor maintenance.[12]

London's independent millers celebrated, with placards reading, "Success to the mills of Albion but no Albion Mills."[13] Opponents referred to the factory as satanic, and accused its owners of adulterating flour and using cheap imports at the expense of British producers. A contemporary illustration of the fire shows a devil squatting on the building.[14] The mill was a short distance from Blake's home.

Blake's phrase resonates with a broader theme in his works; what he envisioned as a physically and spiritually

And all the Arts of Life they changed into the Arts of Death in Albion./...

Jerusalem Chapter 3. William Blake

Another interpretation is that the phrase refers to the established Church of England, which, in contrast to Blake, preached a doctrine of conformity to the established social order and class system. Stonehenge and other megaliths are featured in Milton, suggesting they may relate to the oppressive power of priestcraft in general. Peter Porter observed that many scholars argue that the "[mills] are churches and not the factories of the Industrial Revolution everyone else takes them for".[17] In 2007, the Bishop of Durham, N. T. Wright, explicitly recognised that element of English subculture when he acknowledged the view that "dark satanic mills" could refer to the "great churches".[18] In similar vein, the critic F. W. Bateson noted how "the adoption by the Churches and women's organizations of this anti-clerical paean of free love is amusing evidence of the carelessness with which poetry is read".[19]

An alternative theory is that Blake is referring to a mystical concept within his own mythology, related to the ancient history of England. Satan's "mills" are referred to repeatedly in the main poem, and are first described in words which suggest neither industrialism nor ancient megaliths, but rather something more abstract: "the starry Mills of Satan/ Are built beneath the earth and waters of the Mundane Shell...To Mortals thy Mills seem everything, and the Harrow of Shaddai / A scheme of human conduct invisible and incomprehensible".[20]

"Chariots of fire"

The line from the poem "Bring me my Chariot of fire!" draws on the story of 2 Kings 2:11, where the Old Testament prophet Elijah is taken directly to heaven: "And it came to pass, as they still went on, and talked, that, behold, there appeared a chariot of fire, and horses of fire, and parted them both asunder; and Elijah went up by a whirlwind into heaven." The phrase has become a byword for divine energy, and inspired the title of the 1981 film Chariots of Fire, in which the hymn "Jerusalem" is sung during the final scenes. The plural phrase "chariots of fire" refers to 2 Kings 6:17.

"Green and pleasant land"

Blake lived in London for most of his life, but wrote much of Milton while living in a cottage, now

The phrase "green and pleasant land" has become a common term for an identifiably English landscape or society. It appears as a headline, title or sub-title in numerous articles and books. Sometimes it refers, whether with appreciation, nostalgia or critical analysis, to idyllic or enigmatic aspects of the English countryside.[24] In other contexts it can suggest the perceived habits and aspirations of rural middle-class life.[25] Sometimes it is used ironically,[26] e.g. in the Dire Straits song "Iron Hand".

Revolution

Several of Blake's poems and paintings express a notion of universal humanity: "As all men are alike (tho' infinitely various)". He retained an active interest in social and political events for all his life, but was often forced to resort to cloaking social idealism and political statements in Protestant mystical allegory. Even though the poem was written during the Napoleonic Wars, Blake was an outspoken supporter of the French Revolution, and Napoleon claimed to be continuing this revolution.[27] The poem expressed his desire for radical change without overt sedition. In 1803 Blake was charged at Chichester with high treason for having "uttered seditious and treasonable expressions", but was acquitted. The trial was not a direct result of anything he had written, but comments he had made in conversation, including "Damn the King!".[28]

The poem is followed in the preface by a quotation from Numbers 11:29: "Would to God that all the Lords people were prophets." Christopher Rowland has argued that this includes

everyone in the task of speaking out about what they saw. Prophecy for Blake, however, was not a prediction of the end of the world, but telling the truth as best a person can about what he or she sees, fortified by insight and an "honest persuasion" that with personal struggle, things could be improved. A human being observes, is indignant and speaks out: it's a basic political maxim which is necessary for any age. Blake wanted to stir people from their intellectual slumbers, and the daily grind of their toil, to see that they were captivated in the grip of a culture which kept them thinking in ways which served the interests of the powerful.[8]

The words of the poem "stress the importance of people taking responsibility for change and building a better society 'in Englands green and pleasant land.' "[8]

Popularisation

The poem, which was little known during the century which followed its writing,[29] was included in the patriotic anthology of verse The Spirit of Man, edited by the Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Robert Bridges, and published in 1916, at a time when morale had begun to decline because of the high number of casualties in World War I and the perception that there was no end in sight.[30]

Under these circumstances, Bridges, finding the poem an appropriate hymn text to "brace the spirit of the nation [to] accept with cheerfulness all the sacrifices necessary,"[31] asked Sir Hubert Parry to put it to music for a Fight for Right campaign meeting in London's Queen's Hall. Bridges asked Parry to supply "suitable, simple music to Blake's stanzas – music that an audience could take up and join in", and added that, if Parry could not do it himself, he might delegate the task to George Butterworth.[32]

The poem's idealistic

Setting to music

By Hubert Parry

| "Jerusalem" | |

|---|---|

| Anthem by Hubert Parry | |

The composer, c. 1916 | |

| Key | D major |

| Text | "And did those feet in ancient time" by William Blake (1804) |

| Language | English |

| Composed | 10 March 1916 |

| Duration | 2:45 |

| Scoring | |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 28 March 1916 |

| Location | Queen's Hall, Langham Place, London |

| Conductor | Hubert Parry |

| Audio sample | |

Parry’s arrangement rendered electronically | |

In adapting Blake's poem as a unison song, Parry deployed a two-stanza format, each taking up eight lines of Blake's original poem. He added a four-bar musical introduction to each verse and a coda, echoing melodic motifs of the song. The word "those" was substituted for "these" before "dark satanic mills".

Parry was initially reluctant to supply music for the campaign meeting, as he had doubts about the ultra-patriotism of Fight for Right; but knowing that his former student Walford Davies was to conduct the performance, and not wanting to disappoint either Robert Bridges or Davies, he agreed, writing it on 10 March 1916, and handing the manuscript to Davies with the comment, "Here's a tune for you, old chap. Do what you like with it."[35] Davies later recalled,

We looked at [the manuscript] together in his room at the Royal College of Music, and I recall vividly his unwonted happiness over it ... He ceased to speak, and put his finger on the note D in the second stanza where the words 'O clouds unfold' break his rhythm. I do not think any word passed about it, yet he made it perfectly clear that this was the one note and one moment of the song which he treasured ...[36]

Davies arranged for the vocal score to be published by Curwen in time for the concert at the Queen's Hall on 28 March and began rehearsing it.[37] It was a success and was taken up generally.

But Parry began to have misgivings again about Fight for Right, and in May 1917 wrote to the organisation's founder Sir Francis Younghusband withdrawing his support entirely. There was even concern that the composer might withdraw the song from all public use, but the situation was saved by Millicent Fawcett of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). The song had been taken up by the Suffragists in 1917 and Fawcett asked Parry if it might be used at a Suffrage Demonstration Concert on 13 March 1918. Parry was delighted and orchestrated the piece for the concert (it had originally been for voices and organ). After the concert, Fawcett asked the composer if it might become the Women Voters' Hymn. Parry wrote back, "I wish indeed it might become the Women Voters' hymn, as you suggest. People seem to enjoy singing it. And having the vote ought to diffuse a good deal of joy too. So they would combine happily".[36]

Accordingly, he assigned the copyright to the NUWSS. When that organisation was wound up in 1928, Parry's executors reassigned the copyright to the

The song was first called "And Did Those Feet in Ancient Time" and the early scores have this title. The change to "Jerusalem" seems to have been made about the time of the 1918 Suffrage Demonstration Concert, perhaps when the orchestral score was published (Parry's manuscript of the orchestral score has the old title crossed out and "Jerusalem" inserted in a different hand).

By Wallen

In 2020 a new musical arrangement of the poem by Errollyn Wallen, a British composer born in Belize, was sung by South African soprano Golda Schultz at the Last Night of the Proms. Parry's version was traditionally sung at the Last Night, with Elgar's orchestration; the new version, with different rhythms, dissonance, and reference to the blues, caused much controversy.[4]

Use as a hymn

Although Parry composed the music as a unison song, many churches have adopted "Jerusalem" as a four-part hymn; a number of English entities, including the BBC, the Crown, cathedrals, churches, and chapels regularly use it as an office or recessional hymn on Saint George's Day.[40][citation needed]

However, some clergy in the Church of England, according to the

Many schools use the song, especially

It has been sung on BBC's