Jewish culture

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2023) |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Jewish culture |

|---|

|

| Judaism portal |

Jewish culture is the culture of the

History

There has not been a political unity of Jewish society since the

While there has been communication and traffic between these Jewish communities, many Sephardic exiles blended into the Ashkenazi communities which existed in Central Europe following the

Medieval Jewish communities in Eastern Europe continued to display distinct cultural traits over the centuries. Despite the universalist leanings of the Enlightenment (and its echo within Judaism in the Haskalah movement), many Yiddish-speaking Jews in Eastern Europe continued to see themselves as forming a distinct national group — " 'am yehudi", from the Biblical Hebrew – but, adapting this idea to Enlightenment values, they assimilated the concept as that of an ethnic group whose identity did not depend on religion, which under Enlightenment thinking fell under a separate category.

Constantin Măciucă writes of the existence of "a differentiated but not isolated Jewish spirit" permeating the culture of Yiddish-speaking Jews.[4] This was only intensified as the rise of Romanticism amplified the sense of national identity across Europe generally. Thus, for example, members of the General Jewish Labour Bund in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were generally non-religious, and one of the historical leaders of the Bund was the child of converts to Christianity, though not a practicing or believing Christian himself.[citation needed]

The

Defining secular culture among those who practice traditional Judaism is difficult, because the entire culture is, by definition, entwined with religious traditions: the idea of separate ethnic and religious identity is foreign to the Hebrew tradition of an " 'am yisrael". (This is particularly true for Orthodox Judaism.) Gary Tobin, head of the Institute for Jewish and Community Research, said of traditional Jewish culture:

The dichotomy between religion and culture doesn't really exist. Every religious attribute is filled with culture; every cultural act filled with religiosity. Synagogues themselves are great centers of Jewish culture. After all, what is life really about? Food, relationships, enrichment … So is Jewish life. So many of our traditions inherently contain aspects of culture. Look at the Passover Seder — it's essentially great theater. Jewish education and religiosity bereft of culture is not as interesting.[5]

Yaakov Malkin, Professor of Aesthetics and Rhetoric at Tel Aviv University and the founder and academic director of Meitar College for Judaism as Culture[6] in Jerusalem, writes:

Today very many secular Jews take part in Jewish cultural activities, such as celebrating Jewish holidays as historical and nature festivals, imbued with new content and form, or marking life-cycle events such as birth, bar/bat mitzvah, marriage, and mourning in a secular fashion. They come together to study topics pertaining to Jewish culture and its relation to other cultures, in havurot, cultural associations, and secular synagogues, and they participate in public and political action coordinated by secular Jewish movements, such as the former movement to free Soviet Jews, and movements to combat pogroms, discrimination, and religious coercion. Jewish secular humanistic education inculcates universal moral values through classic Jewish and world literature and through organizations for social change that aspire to ideals of justice and charity.[7]

In North America, the secular and cultural Jewish movements are divided into three umbrella organizations: the

Philosophy and religion

Jewish philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. The Jewish philosophy is extended over several main eras in Jewish history, including the ancient and biblical era, medieval era and modern era (see Haskalah).

The ancient Jewish philosophy is expressed in the bible. According to Prof. Israel Efros the principles of the Jewish philosophy start in the bible, where the foundations of the Jewish monotheistic beliefs can be found, such as the belief in

During the

Between the

Philosophy by Jews in

| Philo (c. 25 BCE–c. 50 CE)) |

Nahmanides (1194–1270) |

Maimonides (1135/1138–1204) |

Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) |

Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1786) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Schneur Zalman of Liadi (1745–1812) |

Emma Goldman (1869–1940) |

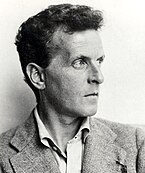

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) |

Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) |

Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902–1994) |

|

|

|

|

|

Education and politics

A range of moral and political views is evident early in the history of Judaism, that serves to partially explain the diversity that is apparent among secular Jews who are often influenced by moral beliefs that can be found in Jewish scripture, and traditions. In recent centuries, secular Jews in Europe and the Americas have tended towards the

Economic activity

In the

However, in almost every instance where large amounts were acquired by Jews through banking transactions the property thus acquired fell either during their life or upon their death into the hands of the king. This happened to Aaron of Lincoln in England, Ezmel de Ablitas in Navarre, Heliot de Vesoul in Provence, Benveniste de Porta in Aragon, etc. It was often for this reason that kings supported the Jews, and even objected to them becoming Christians (because in that case their fortunes earned by usury could not be seized by the crown after their deaths). Thus, both in England and in France the kings demanded to be compensated by the church for every Jew converted. This type of royal trickery was one factor in creating the stereotypical Jewish role of banker and/or merchant.

As a modern system of capital began to develop, loans became necessary for commerce and industry. Jews were able to gain a foothold in the new field of finance by providing these services: as non-Catholics, they were not bound by the ecclesiastical prohibition against "usury"; and in terms of Judaism itself, Hillel had long ago re-interpreted the Torah's ban on charging interest, allowing interest when it is needed to make a living.[citation needed]

Science and technology

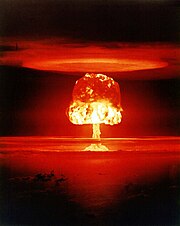

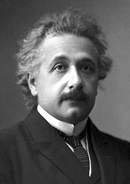

The strong Jewish tradition of religious scholarship often left Jews well prepared for secular scholarship. In some times and places, this was countered by banning Jews from studying at universities, or admitting them only in limited numbers (see Jewish quota). Over the centuries, Jews have been poorly represented among land-holding classes, but far better represented in academia, professions, finance, commerce and many scientific fields. The strong representation of Jews in science and academia is evidenced by the fact that 193 persons known to be Jews or of Jewish ancestry have been awarded the Nobel Prize, accounting for 22% of all individual recipients worldwide between 1901 and 2014.[21] Of whom, 26% in physics,[22] 22% in chemistry[23] and 27% in Physiology or Medicine.[24] In the fields of mathematics and computer science, 31% of Turing Award recipients[25] and 27% of Fields Medal in mathematics[26] were or are Jewish.

The early Jewish activity in science can be found in the

The Torah proscribes Intercropping (Lev. 19:19, Deut 22:9), a practice often associated with sustainable agriculture and organic farming in modern agricultural science.[31][32] The Mosaic code has provisions concerning the conservation of natural resources, such as trees (Deuteronomy 20:19–20) and birds (Deuteronomy 22:6–7).

During Medieval era astronomy was a primary field among Jewish scholars and was widely studied and practiced.

The

The mathematician and physicist

More remarkable contributors include

.Beside Scientific discoveries and researches, Jews have created significant and influential innovations in a large variety of fields such as the listed samples:

| Garcia de Orta (1501/2–1568) |

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) |

Albert Einstein (1879–1955) |

Emmy Noether (1882–1935) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |

| Niels Bohr (1885–1962) |

John von Neumann (1903–1957) |

Robert Oppenheimer (1904–1967) |

Richard Feynman (1918–1988) |

|

|

|

|

Literature and poetry

In some places where there have been relatively high concentrations of Jews, distinct secular Jewish subcultures have arisen.[52] For example, ethnic Jews formed an enormous proportion of the literary and artistic life of Vienna, Austria at the end of the 19th century, or of New York City 50 years later (and Los Angeles in the mid-late 20th century). Many of these creative Jews were not particularly religious people. In general, Jewish artistic culture in various periods reflected the culture in which they lived.

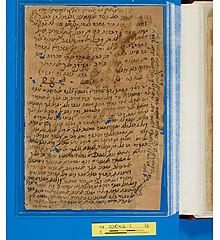

Literary and theatrical expressions of secular Jewish culture may be in specifically Jewish languages such as

Jewish authors have both created a unique Jewish literature and contributed to the national literature of many of the countries in which they live. Though not strictly secular, the Yiddish works of authors like Sholem Aleichem (whose collected works amounted to 28 volumes) and Isaac Bashevis Singer (winner of the 1978 Nobel Prize), form their own canon, focusing on the Jewish experience in both Eastern Europe, and in America. In the United States, Jewish writers like Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, and many others are considered among the greatest American authors, and incorporate a distinctly secular Jewish view into many of their works. The poetry of Allen Ginsberg often touches on Jewish themes (notably the early autobiographical works such as Howl and Kaddish). Other famous Jewish authors that made contributions to world literature include Heinrich Heine, German poet, Mordecai Richler, Canadian author, Isaac Babel, Russian author, Franz Kafka, of Prague, and Harry Mulisch, whose novel The Discovery of Heaven was revealed by a 2007 poll as the "Best Dutch Book Ever".[54]

In Modern Judaism: An Oxford Guide,

Other notable contributors are

Among recipient of Nobel Prize in Literature, 13% were or are Jewish.[58]

Another aspect of Jewish literature is the ethical, called Musar literature. This literature has been composed by both religious and secular authors.[59]

Yehuda Halevi (c. 1075–1141) |

Heinrich Heine (1797–1856) |

Sholem Aleichem (1859–1916) |

Franz Kafka (1883–1924) |

Boris Pasternak (1890–1960) |

Ayn Rand (1905–1982) |

Isaac Asimov (1920–1992) |

Allen Ginsberg (1926–1997) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Theatre

Yiddish theatre

The

in 1876. The next year, his troupe achieved enormous success inYiddish theater in New York in the early 20th century rivalled English-language theater in quantity and often surpassed it in quality. A 1925

In fact, however, the next generation of American Jews spoke mainly English to the exclusion of Yiddish; they brought the artistic energy of Yiddish theater into the American theatrical mainstream, but usually in a less specifically Jewish form.

Yiddish theater, most notably

Montreal's Dora Wasserman Yiddish Theatre continues to thrive after 50 years of performance.

European theatre

From their

The area where Jewish influence was strongest was the theatre, especially in Berlin. Playwrights like

Max Reinhardt, appeared at times to dominate the stage, which tended to be modishly left-wing, pro-republican, experimental and sexually daring. But it was certainly not revolutionary, and it was cosmopolitan rather than Jewish.[62]

Jews also made similar, if not as massive, contributions to theatre and drama in Austria, Britain, France, and Russia (in the national languages of those countries). Jews in Vienna, Paris and German cities found cabaret both a popular and effective means of expression, as German cabaret in the Weimar Republic "was mostly a Jewish art form".[63] The involvement of Jews in Central European theatre was halted during the rise of the Nazis and the purging of Jews from cultural posts, though many emigrated to Western Europe or the United States and continued working there.

English-language theatre

In the early 20th century the traditions of New York's vibrant Yiddish Theatre District both rivaled and fed into Broadway. In the English-speaking theatre Jewish émigrés brought novel theatrical ideas from Europe, such as the

…the Jewish experience has always been best expressed by music, and Broadway has always been an integral part of the Jewish American experience… The difference is that one can expand the definition of "Jewish Broadway" to include an interdisciplinary roadway with a wide range of artistic activities packed onto one avenue—theatre, opera, symphony, ballet, publishing companies, choirs, synagogues and more. This vibrant landscape reflects the life, times and creative output of the Jewish American artist.[68]

In the 19th and early 20th centuries the European

By 1910 Jews (the vast majority of them immigrants from Eastern Europe) already composed a quarter of the population of New York City, and almost immediately Jewish artists and intellectuals began to show their influence on the cultural life of that city, and through time, the country as a whole. Likewise, while the modern musical can best be described as a fusion of operetta, earlier American entertainment and African-American culture and music, as well as Jewish culture and music, the actual authors of the first "book musicals" were the Jewish

One explanation of the affinity of Jewish composers and playwrights to the musical is that "traditional Jewish religious music was most often led by a single singer, a cantor while Christians emphasize choral singing."[72] Many of these writers used the musical to explore issues relating to

The ranks of prominent Jewish producers, directors, designers and performers include

The

Hebrew and Israeli theatre

The earliest known

Modern Hebrew theatre and drama, however, began with the development of

Judeo-Tat theatre

The first theatrical event by Mountain Jews took place in December 1903,[81] when Asaf Agarunov, a teacher and a Zionist, staged a story by Naum Shoykovich, translated from Hebrew, "The Burn for Burn," and staged it in honor of schoolteacher Nagdimuna ben Simona's (Shimunov) wedding.[81]

In 1918, a drama studio was opened in Derbent, Soviet Union headed by Rabbi Yashaiyo Rabinovich.[81]

In 1935, the first Soviet Union theatre opened in Derbent, which included three troupes – Russian, Mountain Jews and Turk. It was based on drama circles, which were led by Manashir and Khanum Shalumov. Initially, in the circle, men played the female roles. Later, women began to take part in the theatre.[82] In 1939, the Judeo-Tat theatre was the winner of the festival of theatres in Dagestan.

During World War II, most of the actors were drafted into the army. Many theatre actors died in the war.[83] In 1943, the theatre resumed its work, and in 1948 it was closed. The official reason was its unprofitability.[83]

In the 1960s, the theatre resumed its activities and experienced its second heyday. The actress, Akhso Ilyaguevna Shalumova (1909-1985), "Honored Artist of the

In the 1970s, the People's Judeo-Tat theatre was organized. For many years, its director was Abram Avdalimov, "Honored Cultural Worker of the Dagestan ASSR," singer, actor and playwright. His successor was Roman Izyaev, who was awarded the Order of the Badge of Honour for his meritorious service.[83]

In the 1990s, the Judeo-Tat theatre experienced another crisis: it rarely held performances and did not have any premieres. Only in 2000, when it became a municipal theater, was it able to resume its activity. From 2000 to 2002, the theatre was headed by actor and musician Raziil Semenovich Ilyaguev (1945-2016), "Honored Worker of Culture of the Republic of Dagestan." For the next two years the theatre was headed by Alesya Isakova.

In 2004, Lev Yakovlevich Manakhimov (1950-2021), "Honored Artist of the Republic of Dagestan," became the artistic director of the theatre. After the death of Manakhimov, Boris Yudaev became the head of the theatre.

Cinema

In the era when Yiddish theatre was still a major force in the world of theatre, over 100 films were made in Yiddish. Many are now lost. Prominent films included

The roster of Jewish entrepreneurs in the English-language American film industry is legendary:

It would be ... pointless to look for consciously Jewish elements in the songs of Irving Berlin or the Hollywood movies of the era of the great studios, all of which were run by immigrant Jews: their object, in which they succeeded, was precisely to make songs or films which found a specific expression for 100 per cent Americanness.

A more specifically Jewish sensibility can be seen in the films of the Marx Brothers, Mel Brooks, or Woody Allen; other examples of specifically Jewish films from the Hollywood film industry are the Barbra Streisand vehicle Yentl (1983), or John Frankenheimer's The Fixer (1968). More recently, Call Me By Your Name (2017) can be given as an example of a movie with Jewish sensibility. Jewish film festivals are nowadays conducted in many major cities around the world as vehicles of introducing such films to wider audiences, including among others the Boston JFF, San Francisco JFF, Jerusalem JFF, etc

Radio and television

The first radio chains, the

Although there is little specifically Jewish television in the United States (National Jewish Television, largely religious, broadcasts only three hours a week), Jews have been involved in American television from its earliest days. From Sid Caesar and Milton Berle to Joan Rivers, Gilda Radner, and Andy Kaufman to Billy Crystal to Jerry Seinfeld, Jewish stand-up comedians have been icons of American television. Other Jews that held a prominent role in early radio and television were Eddie Cantor, Al Jolson, Jack Benny, Walter Winchell and David Susskind. More figures are Larry King, Michael Savage and Howard Stern. In the analysis of Paul Johnson, "The Broadway musical, radio and TV were all examples of a fundamental principle in Jewish diaspora history: Jews opening up a completely new field in business and culture, a tabula rasa on which to set their mark, before other interests had a chance to take possession, erect guild or professional fortifications and deny them entry."[86]

One of the first televised

More recently, American Jews have been instrumental to "novelistic" television series such as

Music

Jewish musical contributions also tend to reflect the cultures of the countries in which Jews live, the most notable examples being

.Classical music

Before

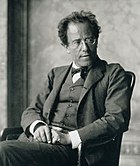

While orchestral and operatic music works by Jewish composers would in general be considered secular, many Jewish (as well as non-Jewish) composers have incorporated Jewish themes and motives into their music. Sometimes this is done covertly, such as the klezmer band music that many critics and observers believe lies in the third movement of Mahler's Symphony No. 1, and this type of Jewish reference was most common during the 19th century when openly displaying one's Jewishness would most likely hamper a Jew's chances at assimilation. During the 20th century, however, many Jewish composers wrote music with direct Jewish references and themes, e.g. David Amram (Symphony – "Songs of the Soul"), Leonard Bernstein (Kaddish Symphony, Chichester Psalms), Ernest Bloch (Schelomo), Arnold Schoenberg, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (Violin Concerto no. 2) Kurt Weill (The Eternal Road) and Hugo Weisgall (Psalm of the Instant Dove).

| Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791–1864) |

Fanny Mendelssohn (1805–1847) |

Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) |

Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813–1888) |

Jacques Offenbach (1819–1880) |

Anton Rubinstein (1829–1894) |

Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) |

Clara Haskil (1895–1960) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In the late twentieth century, prominent composers like Morton Feldman, Gyorgy Ligeti or Alfred Schnittke gave significant contributions to the history of contemporary music.

Popular music

The

Dance

Deriving from Biblical traditions, Jewish dance has long been used by Jews as a medium for the expression of joy and other communal emotions.[88] Each Jewish diasporic community developed its own dance traditions for wedding celebrations and other distinguished events. For Ashkenazi Jews in Eastern Europe, for example, dances, whose names corresponded to the different forms of klezmer music that were played, were an obvious staple of the wedding ceremony of the shtetl.[89] Jewish dances both were influenced by surrounding Gentile traditions and Jewish sources preserved over time. "Nevertheless the Jews practiced a corporeal expressive language that was highly differentiated from that of the non-Jewish peoples of their neighborhood, mainly through motions of the hands and arms, with more intricate legwork by the younger men."[90] In general, however, in most religiously traditional communities, members of the opposite sex dancing together or dancing at times other than at these events was frowned upon.

Humor

The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (April 2017) |

Jewish humor is the long tradition of humor in Judaism dating back to the Torah and the Midrash, but generally refers to the more recent stream of verbal, frequently self-deprecating and often anecdotal humor originating in Europe.[91] Jewish humor took root in the United States over the last hundred years, beginning with vaudeville[citation needed], and continuing through radio, stand-up, film, and television.[92] A significant number of American comedians have been or are Jewish.[citation needed] Notable Jewish-American comedians include Jerry Seinfeld, Larry David, Sammy Davis Jr, Rachel Dratch, Gilbert Gottfried, Ilana Glazer, Jan Murray, Julie Klausner, Don Rickles, Andy Samberg, Gene Wilder, Groucho Marx, Gianmarco Soresi, and several others.

Visual arts

Compared to music or theater, there is less of a specifically Jewish tradition in the visual arts. The most likely and accepted reason is that, as has been previously shown with Jewish music and literature, before

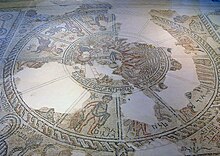

A Jewish tradition of

Again, the arrival of the Jewish artist was a strange phenomenon. It is true that, over the centuries, there had been many animals (though few humans) depicted in Jewish art: lions on

There were few Jewish secular artists in Europe prior to the

During the early 20th century, Jews figured particularly prominently in the École de Paris centered in the Montparnasse movement (including Chaim Soutine, Marc Chagall, Jules Pascin, Yitzhak Frenkel Frenel and Michel Kikoine),[103] and after World War II among the abstract expressionists: Alexander Bogen, Helen Frankenthaler, Adolph Gottlieb, Philip Guston, Al Held, Lee Krasner, Barnett Newman, Milton Resnick, Jack Tworkov, Mark Rothko, and Louis Schanker, as well as among Contemporary artists, Modernists and Postmodernists.[104] Many Russian Jews were prominent in the art of scenic design, particularly the aforementioned Chagall and Aronson, as well as the revolutionary Léon Bakst, who like the other two also painted. One Mexican Jewish artist was Pedro Friedeberg; historians disagree as to whether Frida Kahlo's father was Jewish or Lutheran. Among major artists Chagall may be the most specifically Jewish in his themes. But as art fades into graphic design, Jewish names and themes become more prominent: Leonard Baskin, Al Hirschfeld, Peter Max, Ben Shahn, Art Spiegelman and Saul Steinberg.

The collage artist

Jews have also played a very important role in media other than painting; their involvement in sculpture came rather later, perhaps due to lingering feelings against "graven images". But there were many notable Jewish sculptors in the later 19th and 20th centuries, including Moses Jacob Ezekiel (American, d 1917), Sir Jacob Epstein (American-British, d 1959), Ossip Zadkine (French, d 1967) Naum Gabo (Russian, d 1977), Oscar Nemon (Croatian, d 1985), Louise Nevelson (American, d 1988), Herbert Ferber (American, d 1991).

In photography some notable figures are André Kertész, Robert Frank, Helmut Newton, Garry Winogrand, Cindy Sherman, Steve Lehman,[108] and Adi Nes; in installation art and street art some notable figures are Sigalit Landau,[109] Dede,[110] and Michal Rovner.

| Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) |

Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920) |

Diego Rivera (1886–1957) |

Alexander Bogen (1916–2010) |

Marc Chagall (1887–1985) |

Isaac Frenkel Frenel (1899–1981) |

Chaim Soutine (1893–1943) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Comics, cartoons, and animation

Graphic art, as expressed in the art of comics, has been a key field for Jewish artists as well. In the Golden and Silver ages of American comic books, the Jewish role was overwhelming and a large number of the medium's foremost creators have been Jewish.[111]

Max Gaines was a pioneering figure in the creation of the modern comic book when in 1935 he published the first one called Famous Funnies.[112] In 1939, he founded, with Jack Liebowitz and Harry Donenfeld, All-American Publications (the AA Group).[113] The publication is known for the creation of several superheroes such as the original Atom, Flash, Green Lantern, Hawkman, and Wonder Woman. Donenfeld and Liebowitz were also the owners of National Allied Publications which distributed Detective Comics and Action Comics. That company was also a precursor of DC Comics.

In 1939, the pulp magazine publisher Martin Goodman formed Timely Publications,[114] a company to be known, since the 1960s, as Marvel Comics. At Marvel, Artists such as Stan Lee, Jack Kirby,[115] Larry Lieber and Joe Simon created a large variety of characters and cultural icons including Spider-Man, Hulk, Captain America, Iron Man, Thor, Daredevil, and the teams Fantastic Four, Avengers, X-Men (including many of its characters) and S.H.I.E.L.D.. Stan Lee attributed the Jewish role in comics to the Jewish culture.[116]

At DC Comics Jewish role was significant as well; the character of Superman, which was created by the Jewish artists Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel,[111] is partly based on the biblical figure of Samson.[117] It was also suggested the Superman is partly influenced by Moses,[118][119] and other Jewish elements. More at DC Comics are

In 1944, Max Gaines founded EC Comics.[121] The company is known for specializing in horror fiction, crime fiction, satire, military fiction and science fiction from the 1940s through the mid-1950s, notably the Tales from the Crypt series, The Haunt of Fear, The Vault of Horror, Crime SuspenStories and Shock SuspenStories. Jewish artists that are associated with the publisher include Al Feldstein, Dave Berg, and Jack Kamen.

In 1952, William Gaines and Harvey Kurtzman founded Mad, an American humor magazine. It was widely imitated and influential, affecting satirical media as well as the cultural landscape of the 20th century, with editor Al Feldstein increasing readership to more than two million during its 1970s circulation peak.[123] Other known cartoonists are Lee Falk creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician; The Hebrew comics of Michael Netzer creator of Uri-On and Uri Fink creator of Zbeng!; William Steig, creator of Shrek!; Daniel Clowes, creator of Eightball; Art Spiegelman creator of graphic novel Maus and Raw (with Françoise Mouly).

In animation, Jewish animators role is expressed by many: Genndy Tartakovsky is the creator of several animation TV series such as Dexter's Laboratory and Samurai Jack;[124] Matt Stone co-creator of South Park; David Hilberman who helped animate Bambi and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs; Friz Freleng, Looney Tunes;C. H. Greenblatt,Chowder; and Harvey Beaks; Ralph Bakshi, Fritz the Cat, Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures, Wizards, The Lord of the Rings, Heavy Traffic, Coonskin, Hey Good Lookin', Fire and Ice, and Cool World;[125] Alex Hirsch, creator of Gravity Falls; Dave Fleischer and Lou Fleischer, founders of Fleischer Studios; Max Fleischer, animation of Betty Boop, Popeye and Superman; Rebecca Sugar, creator of Steven Universe.[126] Several companies producing animation were founded by Jews, such as DreamWorks, which its products include Shrek, Madagascar, Kung Fu Panda and The Prince of Egypt; Warner Bros., whose animation division is known for cartoons such as Looney Tunes, Tiny Toon Adventures, Animaniacs, Pinky and the Brain and Freakazoid! .

Cuisine

Jewish cooking combines the food of many cultures in which Jews have lived, including

.Philo-Semitism

Very few Jews live in East Asian countries, but Jews are viewed in an especially positive light in some of them, partly owing to their shared wartime experiences during the Second World War. Examples include South Korea[135] and China.[136] In general, Jews are positively stereotyped as being intelligent, business savvy and committed to family values and responsibilities, but in the Western world, the first of the two aforementioned stereotypes more frequently have the negatively interpreted equivalents of guile and greed. In South Korean primary schools, students are required to read the Talmud.[135]

See also

- Culture of Israel

- Visual arts in Israel

- Humanistic Judaism

- Jewish folklore

- Jewish studies

- Jews and Christmas

- Secular Culture & Ideas

- Traditional Jewish chronology

- Yiddishkeit

References

- ^ Lawrence Schiffman, Understanding Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism. KTAV Publishing House, 2003. p. 3.

- ^ Biale, David, Not in the Heavens: The Tradition of Jewish Secular Thought, Princeton University Press, 2011, pp.5–6, 15

- ^ Torstrick, Rebecca L., Culture and customs of Israel, Greenwood Press, 2004

- ISBN 973-98272-2-5. See the article on the authorfor further information.

- ^ The Emergence of a Jewish Cultural Identity Archived 2005-10-28 at the Wayback Machine, undated (2002 or later) on MyJewishLearning.com, reprinted from the National Foundation for Jewish Culture. Accessed 11 February 2006.

- ^ "Meitar.org". meitar.org.il. Archived from the original on May 10, 2006. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Malkin, Y. "Humanistic and secular Judaisms." Modern Judaism An Oxford Guide, p. 107.

- ^ "Medieval Philosophy and the Classical Tradition: In Islam, Judaism and Christianity" by John Inglis, Page 3

- ^ "Introduction to Philosophy" by Dr Tom Kerns

- ISSN 2161-0002. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ^ Keener, Craig S (2003). The Gospel of John: A Commentary. Vol. 1. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson. pp. 343–347.

- ^ Yalom, Irvin (February 21, 2012). "The Spinoza Problem". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013.

- ^ "Mendelssohn". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ^ Wein (1997), p. 44. (Google books)

- ^ Daniel J. Elazar, Judaism and Democracy: The Reality. Undated. Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Accessed February 11, 2006.

- ^ "A Jewish Fight for Public Education". September 2, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ "The Jewish Americans". PBS. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ Sowell, Thomas (2006). On classical economics. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- ^ "David Ricardo – Policonomics". www.policonomics.com. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- Jewish Encyclopedia(1901–1906).

- ^ "Jewish Nobel Prize Laureates". jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ JINFO. "Jewish Nobel Prize Winners in Physics". jinfo.org.

- ^ JINFO. "Jewish Nobel Prize Winners in Chemistry". www.jinfo.org.

- ^ JINFO. "Jewish Nobel Prize Winners in Medicine". jinfo.org.

- ^ JINFO. "Jewish Recipients of the ACM Turing Award". jinfo.org.

- ^ "Jewish Recipients of the Fields Medal". jinfo.org.

- ^ "Rosalind Franklin :: DNA from the Beginning". www.dnaftb.org. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "Rosalind Franklin: A Crucial Contribution". www.nature.com. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "Rosalind Franklin's contributions to the study of DNA". gmu.edu. Archived from the original on September 6, 2006. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Kurtz, J. H.; Simonton, T. D. (1857). "The Bible and Astronomy; An Exposition of the Biblical Cosmology, and Its Relations to Natural Science". Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston.

- ^ Andrews, D.J., A.H. Kassam. 1976. The importance of multiple cropping in increasing world food supplies. pp. 1–10 in R.I. Papendick, A. Sanchez, G.B. Triplett (Eds.), Multiple Cropping. ASA Special Publication 27. American Society of Agronomy, Madison, Wisconsin.

- JSTOR 2403292.

- ^ "Science in Medieval Jewish Scholarship". myjewishlearning.com. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "Zacuto, Abraham" in Glick, T., S.J. Livesy and F. Williams, editors, (2005) Medieval science, technology, and medicine: an encyclopedia, New York Routledge.

- ISBN 978-0743258210.

- ^ Boaz Tsaban and David Garber. "The proof of Rabbi Abraham Bar Hiya Hanasi". Archived from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ "Garcia de Orta (1501/02-68)". www.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Will, Clifford M (August 1, 2010). "Relativity". Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Will, Clifford M (August 1, 2010). "Space-Time Continuum". Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Will, Clifford M (August 1, 2010). "Fitzgerald–Lorentz contraction". Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ "Jews and the Atom Bomb". May 20, 2015. Archived from the original on May 20, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Ford & Urban 1965, p. 109

- ^ Mannoni, Octave, Freud: The Theory of the Unconscious, London: NLB 1971, p. 49-51

- ^ Mannoni, Octave, Freud: The Theory of the Unconscious, London: NLB 1971, pp. 146–47

- S2CID 4224209.

- Townes, Charles Hard. "The first laser". University of Chicago. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- ^ Regis, Ed (November 8, 1992). "Johnny Jiggles the Planet". The New York Times. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ Glimm, p. vii

- ^ Einstein, Albert (May 1, 1935), "Professor Einstein Writes in Appreciation of a Fellow-Mathematician", New York Times (May 5, 1935), retrieved April 13, 2008. Online at the MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- ^ Alexandrov 1981, p. 100.

- OCLC 223099225

- ^ "Literature, Jewish". Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ "biblical literature". britannica.com. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "Leading Dutch writer Mulisch dies". Gulf Daily News. November 1, 2010. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Kamin, Debra (May 20, 2014). "The Jewish legacy behind Game of Thrones". The Times of Israel. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- ^ Martin, George R. R. (April 3, 2013). "My hero: Maurice Druon by George RR Martin". The Guardian. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ Milne, Ben (April 4, 2014). "Game of Thrones: The cult French novel that inspired George RR Martin". BBC. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ JINFO. "Jewish Nobel Prize Winners in Literature". www.jinfo.org.

- ISBN 978-0-8276-1887-9.

- ^ Melamed, S.M., "The Yiddish Stage", New York Times, September 27, 1925 (X2).

- ^ Berlin Metropolis: Jews and the New Culture, 1890–1918 Archived November 5, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, on the site of The Jewish Museum, New York. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- ^ Johnson, Paul (1987). A History of the Jews, pg. 479. New York: Harper Perennial. – Erwin Piscator was a Lutheran Protestant (Nazi propagandists had claimed since 1927 that he was a "Jewish Bolshevik", though).

- ^ Suzanne Weiss, Jewish cabaret singer brings songs of Berlin to Berkeley, The Jewish News Weekly of Northern California, September 27, 1996. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- ^ "Broadway Celebrates 100 Years of National Yiddish Theatre Tonight – Playbill". Playbill. August 5, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Stephen J. Whitfield, Musical Theater (PDF). Brandeis Review, Winter/Spring 2000. Accessed February 11, 2006.

- ^ Samantha M. Shapiro, The Arts: A Jewish Street Called Broadway Archived December 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Hadassah Magazine, October 2004 Vol. 86 No.2. Accessed February 11, 2006.

- ^ Charyn, Jerome. "Early Broadway's un-Jewish Jews." Midstream 50.1 (January 2004): 19(7). Expanded Academic ASAP. Thomson Gale. UC Irvine (CDL). March 9, 2006

- ^ The Klezmer Company Breaks New Ground with Orchestral Klezmer Production "Jewish Broadway with Orchestra and Chorus" at FAU Archived 2006-09-09 at the Wayback Machine. Florida Atlantic University press release, February 8, 2005. Accessed 11 February 2006.

- ^ Raphael Mostel, Carmen Comes Home Archived May 17, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, The Forward, May 7, 2004. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- ^ Dr. Kenneth Libo Ph. D and Michael Skakun, The Persecution of Creativity: Jews, Music and Vienna Archived September 26, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Center for Jewish History, April 16, 2004. Accessed February 12, 2006

- ^ Michael Billig, Creating the American Musical Archived September 28, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Originally from Rock 'N' Roll Jews (Five Leaves Publications), extracted on myjewishlearning.com. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- ^ Jacob Baron, Jewish Composers Archived December 28, 2004, at the Wayback Machine, Machar, The Washington Congregation for Secular Humanistic Judaism, June 2, 2005. Accessed February 15, 2006.

- ^ Alan Gomberg, op. cit.

- ^ Arthur Laurents, Theater: West Side Story; The Growth of an Idea, New York Herald Tribune, August 4, 1957. Reproduced on leonardbernstein.com. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- ^ JINFO. "Jewish Recipients of the Pulitzer Prize for Drama". www.jinfo.org.

- ^ Shimon Levy, The Development of Israeli Theatre– a brief overview Archived August 16, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Credited to Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Jerusalem, 2000. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- Jewish Encyclopedia. Could not access February 12, 2006.

- ^ Shimon Levy, op. cit. Archived August 16, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Orna Ben-Meir, Biblical Thematics in Stage Design for the Hebrew Theatre Archived April 15, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Assaph, Section C, no. 11 (July 1999), p. 141 et. seq.. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- Geocities site, credits habima.org.il Archived November 24, 2005, at the Wayback Machine and cameri.co.il.

- ^ a b c Musakhanova G. B. Judeo-Tat literature. Makhachkala: Dagestan Book Publishing House, 1993.

- ^ P. Agarunov. Theatrical art of Mountain Jews. // Magazine "Minyan", №5.

- ^ a b c d Book (ru:«Самородки Дагестана») – "Gifted of Dagestan". Author: I. Mikhailova. Makhachkala, Russia. 2014.

- ISBN 9780375422348

- ^ Johnson, op. cit.' p. 462-463.

- ^ Johnson, op. cit. p. 462-463.

- ^ "JEWISH MUSIC INSTITUTE – Western Classical Music". www.jmi.org.uk. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Landa, M. J. (1926). The Jew in Drama, p. 17. New York: Ktav Publishing House (1969). Each Jewish diasporic community developed its own dance traditions for wedding celebrations and other distinguished events.

- ^ Yiddish, Klezmer, Ashkenazic or 'shtetl' dances Archived August 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Le Site Genevois de la Musique Klezmer. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- ^ Yiddish, Klezmer, Ashkenazic or 'shtetl' dances, Le Site Genevois de la Musique Klezmer. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- S2CID 162195868. Archived from the originalon October 24, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Leo Rosten, The Joys of Yinglish

- ^ Ismar Schorsch, Shabbat Shekalim Va-Yakhel 5755 Archived October 26, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, commentary on Exodus 35:1 – 38:20. February 25, 1995. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- ^ Velvel Pasternak, Music and Art, part of "12 Paths" on Judaism.com. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- ^ "Not a Pretty Picture". Haaretz. June 27, 2002. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Jessica Spitalnic Brockman, A Brief History of Jewish Art Archived January 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine on MyJewishLearning.com. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- ^ Michael Schirber, Did Christians copy Jewish catacombs?, NBC News, July 20, 2005. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- ^ Jona Lendering, The Jewish diaspora: Rome Archived April 18, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Livius.org. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- ^ Roza Bieliauskiene and Felix Tarm, Brief History of Jewish Art, Jewish Art Network. Accessed January 14, 2010.

- ^ Johnson, op.cit., p. 411.

- ^ "GW Libraries at the George Washington University – GW Libraries". www.gwu.edu. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Rebecca Assoun, Jewish artists in Montparnasse Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. European Jewish Press, July 19, 2005. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- ^ "artnet Galleries: A House in Safed by Yitzhak Frenkel-Frenel from Jordan-Delhaise Gallery". December 3, 2013. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Jewish Artists, Jewish Virtual Library, 2005. Accessed February 12, 2006.

- ^ Mark Bloch (2007). "Semina Culture: Wallace Berman and his Circle at the Grey Art Gallery, New York University". Whitehot Magazine. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ Candida Smith, Richard. (2023). "Utopia and Dissent," Ch 9 Wallace Berman on Public Culture in the Kennedy Years.

- ^ Tom Teicholz (2003). "Kitaj the 'Diasporist'". Jewish Journal. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ foto8.com, John Levy, "Review of The Tibetans", photo 8, amazon.com, Lehman, Steve, The Tibetans: A Struggle to Survive (New York: How Town / Umbrage), 1998.

- ^ See: Ohad Meromi in the online exhibition "Real Time" <http://www.imj.org.il/exhibitions/2008/realtime/Meromi_e.html Archived April 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine>.

- ^ Boulos, Nick (October 5, 2013). "Show and Tel Aviv: Israel's artistic coastal city". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 8, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ ISBN 9780313357473. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ Markstein, Donald D. "Don Markstein's Toonopedia: Famous Funnies". www.toonopedia.com. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "UAHC – Reform Judaism Magazine". reformjudaismmag.net. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ISBN 9781416598459. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ Groth, Gary (May 23, 2012). "Jack Kirby Interview". The Comics Journal. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ Hoffman, Jordan (April 29, 2012). "A marvel in comics". The Times of Israel. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ Petrou, David Michael (1978). The Making of Superman the Movie, New York: Warner Books

- ^ Jacobson, Howard (March 5, 2005). "Up, up and oy vey". The Times (UK). p. 5.

- ^ The Mythology of Superman (DVD). Warner Bros. 2006.

- ^ Baylen, Ashley (May 5, 2012). "Top 10 Jewish Marvel & DC Comics' Superheroes". Shalom Life. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ Markstein, Donald D. "Don Markstein's Toonopedia: EC Comics". www.toonopedia.com. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Inc., Will Eisner Studios. "A short biography - WillEisner.com". willeisner.com. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Winn, Marie (January 25, 1981). "What Became of Childhood Innocence?". The New York Times. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ "The Way of the Samurai". The Jewish Journal. August 3, 2001. Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- ^ "filmography". ralphbakshi.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Screenshot (October 11, 2017). "The Secret Jewish History Of Steven Universe". The Forward. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ Roden, Claudia (1996). "The Book of Jewish Food: An Odyssey from Samarkand to New York”. Excerpt, retrieved April 7, 2015, from My Jewish Learning

- ^ Vered, Ronit (May 13, 2017). "Why are Israeli Jews obsessed with hummus?". Haaretz.

- ^ Eileen M. Lavine (September–October 2011). "Stuffed Cabbage: A Comfort Food for All Ages". Moment Magazine. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ Zeldes, Leah A. (September 1, 2010). "Eat this! Tzimmes, A sweet start to the Jewish New Year". Dining Chicago. Chicago's Restaurant & Entertainment Guide, Inc. Archived from the original on December 30, 2010. Retrieved September 1, 2010.

- ^ Marks, Gil. Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. Houghton Mifflin.

- ^ Roman, Alison (April 2, 2014). "How to Master Matzo Ball Soup". Bon Appetit.

- ^ "The Genealogy of Morals", Part I, Section 16, tr. Walter Kaufmann

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 4 by Erwin Fahlbusch, Geoffrey William Bromiley

- ^ a b Alper, Tim. "Why South Koreans are in love with Judaism". The Jewish Chronicle. May 12, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ^ Nagler-Cohen, Liron. "Chinese: 'Jews make money'". Ynetnews. April 23, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

Sources

- OCLC 7837628.

Further reading

- Landa, M.J. (1926). The Jew in Drama. New York: Ktav Publishing House (1969).

- Stevens, Matthew. Jewish Film Directory: a guide to more than 1200 films of Jewish interest from 32 countries over 85 years. Trowbridge: Flicks Books, 1992 ISBN 0-9489117-2-7298p.

- ISBN 0-385-26557-3.

- Veidlinger, Jeffrey. Jewish Public Culture in the Late Russian Empire. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009.

External links

- The center for Jewish Art Collection

- The City Congregation for Humanistic Judaism

- Congress of Secular Jewish Organizations

- Global Directory of Jewish Museums

- News and reviews about Jewish literature and books

- Festival of Jewish Theater and Ideas Archived January 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- The Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art Archived March 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Heeb – an online magazine about Jewish culture

- Gesher Galicia