Jewish religious movements

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

Jewish religious movements, sometimes called "

In Israel, variation is moderately similar,[2][3][4][5] differing from the west in having roots in the Old Yishuv and pre-to-early-state Yemenite infusion, among other influences. For statistical and practical purposes, the distinctions there are based upon a person's attitude to religion. Most Jewish Israelis classify themselves as "secular" (hiloni), "traditional" (masortim), "religious" (dati) or ultra-religious (haredi).[6][5]

The western and Israeli movements

Other divisions of Judaism in the world reflect being more

Terminology

Some Jews reject the term denomination as a label for different groups and ideologies within Judaism, arguing that the notion of denomination has a specifically Christian resonance that does not translate easily into the Jewish context. However, in recent years the American Jewish Year Book has adopted "denomination", as have many scholars and theologians.[7]

Commonly used terms are movements,[8][9][10][11][12][13][14][3][15][16][17][18] as well as denominations,[19][20][21][22][7][15][23][24] varieties,[1] traditions,[25] groupings,[17][26] streams,[27] branches,[28] sectors and sects (for some groups),[29][30] trends,[31] and such. Sometimes, as an option, only three main currents of Judaism (Orthodox, Conservative and Reform) are named traditions, and divisions within them are called movements.

The Jewish groups themselves reject characterization as

Sects in the Second Temple period

Prior to the destruction of the

The main internal struggles during this era were between the Pharisees and the Sadducees, as well as the early Christians, and also the Essenes and Zealots. The Pharisees wanted to maintain the authority and traditions of classical Torah teachings and began the early teachings of the

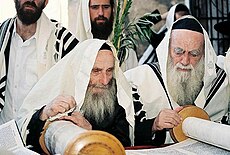

Rabbinic Judaism

Most streams of modern Judaism developed from the Pharisaic movement, which became known as Rabbinic Judaism (in

Non-Rabbinic Judaism

Non-Rabbinic Judaism—Sadducees, Nazarenes, Karaite Judaism, and Haymanot—contrasts with Rabbinic Judaism and does not recognize the Oral Torah as a divine authority nor the rabbinic procedures used to interpret Jewish scripture.[36]

Karaite Judaism

The tradition of the Qara'im survives in Karaite Judaism, started in the early 9th century when non-rabbinic sages like Benjamin Nahawandi and their followers took the rejection of the Oral Torah by Anan ben David to the new level of seeking the plain meaning of the Tanakh's text. Karaite Jews accept only the Tanakh as divinely inspired, not recognizing the authority that Rabbinites ascribe to basic rabbinic works like the Talmud and the Midrashim.[37][38]

Ethno-cultural divisions' movements

Although there are numerous Jewish ethnic communities, there are several that are large enough to be considered predominant. Generally, they do not constitute separate religious branches within Judaism, but rather separate cultural traditions (

The Enlightenment had a tremendous effect on Jewish identity and on ideas about the importance and role of Jewish observance.[40] Due to the geographical distribution and the geopolitical entities affected by the Enlightenment, this philosophical revolution essentially affected only the Ashkenazi community; however, because of the predominance of the Ashkenazi community in Israeli politics and in Jewish leadership worldwide, the effects have been significant for all Jews.[40]

Sephardic and Mizrahi Judaism

Sephardim are primarily the descendants of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula, such as most Jews from France and the Netherlands. They may be divided into the families that left in the Expulsion of 1492 and those that remained as crypto-Jews, Marranos and those who left in the following few centuries. In religious parlance, and by many in modern Israel, the term is used in a broader sense to include all Jews of Ottoman or other Asian or African backgrounds (Mizrahi Jews), whether or not they have any historic link to Spain, although some prefer to distinguish between Sephardim proper and Mizraḥi Jews.

Sephardic and Mizrachi Jewish synagogues are generally considered Orthodox or Sephardic Haredim by non-Sephardic Jews, and are primarily run according to the Orthodox tradition, even though many of the congregants may not keep a level of observance on par with traditional Orthodox belief. For example, many congregants will drive to the synagogue on the Shabbat, in violation of halakha, while discreetly entering the synagogue so as not to offend more observant congregants. However, not all Sephardim are Orthodox; among the pioneers of the Reform Judaism movement in the 1820s there was the Sephardic congregation Beth Elohim in Charleston, South Carolina.[44][45] A part of the European Sephardim were also linked with the Judaic modernization.[46]

Unlike the predominantly Ashkenazic Reform, and Reconstructionist denominations, Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews who are not observant generally believe that Orthodox Judaism's interpretation and legislation of halakha is appropriate, and true to the original philosophy of Judaism. That being said, Sephardic and Mizrachi rabbis tend to hold different, and generally more lenient, positions on halakha than their Ashkenazi counterparts, but since these positions are based on rulings of Talmudic scholars as well as well-documented traditions that can be linked back to well-known codifiers of Jewish law, Ashkenazic and Hasidic Rabbis do not believe that these positions are incorrect, but rather that they are the appropriate interpretation of halakha for Jews of Sephardic and Mizrachi descent.[41][43][47]

The

The Shas, a religious political party in Israel, represents the interests of the Orthodox/Haredi Sephardim and Mizrahim.[49]

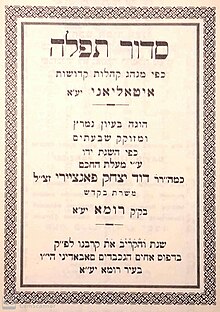

Italian and Romaniote Judaism

A relatively small but influential ethnoreligious group in the intellectual circles of Israel are Italian rite Jews (Italkim) who are neither Ashkenazi nor Sephardi. These are exclusively descendants of the ancient Roman Jewish community, not including later Ashkenazic and Sephardic migrants to Italy. They practice traditional Orthodox Judaism. The liturgy is served according to a special Italian Nusach (Nusach ʾItalqi, a.k.a. Minhag B'nei Romì) and it has similarities with the nusach of the Greek Romaniote Jews.

The Romaniote Jews or the Romaniotes (Romanyotim) native to the Eastern Mediterranean is the oldest Jewish community in Europe, whom name is refers to the Eastern Roman Empire. They are also distinct from the Ashkenazim and Sephardim. But, nowadays, few synagogues still use the Romaniote nusach and minhag.

Ashkenazic movements

Hasidic Judaism

Lithuanian (Lita'im)

In the late 18th century, there was a serious schism between Hasidic and non-Hasidic Jews. European traditionalist Jews who rejected the Hasidic movement were dubbed

Post-Enlightenment movements

Late-18th-century Europe, and then the rest of the world, was swept by a group of intellectual, social and political movements that taken together were referred to as the Enlightenment. These movements promoted scientific thinking, free thought, and allowed people to question previously unshaken religious dogmas. The emancipation of the Jews in many European communities, and the Haskalah movement started by Moses Mendelssohn, brought the Enlightenment to the Jewish community.[40]

In response to the challenges of integrating Jewish life with Enlightenment values, German Jews in the early 19th century began to develop the concept of Reform Judaism, adapting Jewish practice to the new conditions of an increasingly urbanized and secular community. Staunch opponents of the Reform movement became known as Orthodox Jews. Later, members of the Reform movement who felt that it was moving away from tradition too quickly formed the Conservative movement.[63]

At the same time, the notion "traditional Judaism" includes the Orthodox with Conservative[17] or solely the Orthodox Jews[16] or exclusively pre-Hasidic pre-modern forms of Orthodoxy.[64]

Over time, three main movements emerged (Orthodox, Reform and Conservative Judaism).[17][16]

Orthodoxy

Orthodox Jews generally see themselves as practicing normative Judaism, rather than belonging to a particular movement. Within Orthodox Judaism, there is a spectrum of communities and practices, ranging from ultra-Orthodox

In Israel, Orthodox Judaism occupies a privileged position: solely an Orthodox rabbi may become the Chief rabbi and Chief military rabbi; and only Orthodox synagogues have the right to conduct Jewish marriages.[5][68]

Reform

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal (the "Liberal" label can refer only to the British branch)[28] or Progressive Judaism, originally began in Germany, the Netherlands and the United States c. 1820 as a reaction to modernity, stresses assimilation and integration with society and a personal interpretation of the Torah. The German rabbi and scholar Abraham Geiger with principles of Judaism as religion and not ethnicity, progressive revelation, historical-critical approach, the centrality of the Prophetic books, and superiority of ethical aspects to the ceremonial ones has become the main ideologist of the "Classical" Reform. Unlike traditional Judaism, the Reform rejects the concept of the Jews as the chosen people.[8][75][11][76][13][77][78][79][80][45] There are transformations from the purism of "Classical" European to the "New Reform" in America with reincorporation some traditional Jewish elements.[81][82]

In the United States, at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, the Reform movement became the first in terms of numbers, ahead of Conservative Judaism.[83][84] In contrast, Israeli Reform is smaller one.[2][3]

Conservative (Masorti)

Conservative or Masorti Judaism, originated in Germany in the 19th century on the ideological foundation of the Historical School studies,[85] but became institutionalized in the United States, where it was to become the largest Jewish movement[16][18][86] (however, in 1990 Reform Judaism already outpaced Conservatism by 3 percent).[83] After the division between Reform and Orthodox Judaism, the Conservative movement tried to provide Jews seeking liberalization of Orthodox theology and practice, such as female rabbi ordination, with a more traditional and halakhically-based alternative to Reform Judaism. It has spread to Ashkenazi communities in Anglophone countries and Israel.[9][87][11][88][2][3][89][90][18]

Neolog Judaism, a movement in the Kingdom of Hungary and in its territories ceded in 1920, is similar to the more traditional branch of American Conservative Judaism.[91]

Communal Judaism (Ḥevrati)

Communal Judaism, also referred to as יהדות חברתי (Yahadut Ḥevrati) in Hebrew, is a denomination that intertwines the ethnoreligious identity and indigenous tradition within the broader Jewish community. Unlike other movements which may emphasize theological nuances, Communal Judaism places a substantial focus on the social and communal aspects of Jewish life, alongside personal spiritual practices.

Practitioners are diverse, found globally with significant numbers in Israel and the United States, extending to European and Middle Eastern countries. This spread is reflective of the movement's inclusive approach to Jewish identity, welcoming those who align with its core values of maintaining communal traditions and customs without the stringent adherence to rabbinical interpretations that some other denominations might require.[92][93]

In terms of religious observance, adherents commonly engage in the lighting of Shabbat candles, recitation of Kiddush, and the enjoyment of communal meals replete with traditional zemirot. This practice is designed to foster a sense of community and spiritual reflection, particularly on Shabbat where the use of technology is often set aside to maintain a contemplative state.[94][95]

Dietary laws within Communal Judaism adhere to kashrut, the set of Jewish dietary laws, with a focus on traditional observance. This includes abstaining from pork and shellfish and not mixing meat with dairy products, as outlined in the Torah.[96]

The connection to Israel stands as a central tenet of Communal Judaism, emphasizing a deep ethnic heritage and historical relationship with the land. This connection is celebrated and remembered through the observance of holidays and commemorations that reflect on the Jewish people's historical experiences of dispersal and return.[97][98]

Spiritually, Communal Judaism advocates for the integration of tradition into daily life, upholding a heart-centered approach to religious practice. While individual prayer is encouraged, the emphasis is placed on communal worship and support, reflecting the movement's overarching commitment to a life lived in close connection with one's community and heritage.[92][93]

Migration

The particular forms which the denominations have taken on have been shaped by immigration of the Ashkenazi Jewish communities, once concentrated in eastern and central Europe, to western and mostly Anglophone countries (in particular, in North America). In the middle of the 20th century, the institutional division of North American Jewry between Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox movements still reflected immigrant origins. Reform Jews at that time were predominantly of German or western European origin, while both Conservative and Orthodox Judaism came primarily from eastern European countries.[99]

Zionists (Datim-leumi) and anti-Zionists

The issue of Zionism was once very divisive in the Jewish community. Religious Zionism, a.k.a. "Nationalist Orthodoxy" (Dati-leumi) combines Zionism and Orthodox Judaism, based on the teachings of rabbis Zvi Hirsch Kalischer and Abraham Isaac Kook. The name Hardalim or Haredi-leumi ("Nationalist Haredim") refers to the Haredi-oriented variety of Religious Zionism.[100][101][102][103][104][105] Another mode is Reform Zionism as Zionist arm of Reform Judaism.[103]

Non-Orthodox Conservative leaders joined Zionist mission.[15] Reconstructionist Judaism also supports Zionism and "the modern state of Israel plays a central role in its ideology."[106]

Religious Zionists (datim) have embraced the Zionist movement, including Religious Kibbutz Movement, as part of the divine plan to bring or speed up the messianic era.[17][101][107]

Zionism was rejected by most ultra-Orthodox and Reform Jews.

Among most religious non-Zionists, such as Chabad, there is a de facto recognition of Israel, but only as a secular non-religious state.

A few of the fringe groups of the anti-Zionists, with marginal ideology, does not recognize the legitimacy of the Israeli state. Among them are both the Orthodox (the

In addition, according to some contemporary scholars, Religious Zionism stands at least outside of Rabbinic Judaism or ever shoots off Judaism as such.[109][102]

Pressures of assimilation

Among the most striking differences between the Jewish movements in the 21st century is their response to pressures of assimilation, such as

Crypto-Judaism

The secret adherence to Judaism while publicly professing to be of another faith; practitioners are referred to as "crypto-Jews" (origin from Greek kryptos – κρυπτός, 'hidden').[112] Nowadays, in whole, Crypto-Judausm movements are a historical phenomenon.

In the United States,

The Crypto-Jews subgroups are as follows:

- Anusim

- Beta Abraham

- Chala (Jews)

- Sabbateanism

- Frankism

- Dönmeh

- Kaifeng Jews

- Mashhadi Jews

- Neofiti

Other ethnic movements

Beta Israel (Haymanot)

The Beta Israel (House of Israel), also known as Ethiopian Jews, are a Jewish community that developed in Ethiopia and lived there for centuries. Most of the Beta Israel emigrated to Israel in the late 20th century. They practiced Haymanot, a religion which is generally recognized as a non-Rabbinic form of Judaism (in Israel, they practice a mixture of Haymanot and Rabbinic Judaism). To the Beta Israel, the holiest book is the Orit (a word which means the "law"), and it consists of the Torah and the Books of Joshua, Judges and Ruth. Until the middle of the 20th century, the Beta Israel of Ethiopia were the only modern Jewish group which practiced a monastic tradition which the monks adhered to by living in monasteries which were separated from the Jewish villages.[114]

Crimean Karaites

The Crimean Karaites (a.k.a. Karaims) are an ethnicity which is derived from Turkic Karaim-speaking adherents of Karaite Judaism in Eastern Europe, especially in Crimea. They were probably Jewish by origin, but due to political pressure and other reasons, many of them began to claim that they were Turks, descendants of the Khazars. During the era when Crimea was a part of the Russian Empire, the Crimean Karaite leaders persuaded the Russian rulers to exempt Karaites from the anti-Semitic regulations which were imposed upon Jews. These Karaites were recognized as non-Jews during the Nazi occupation. Some of them even served in the SS. The ideology of de-Judaization and the revival of Tengrism were imbued with the works of the contemporary leaders of the Karaites in Crimea. While the members of several Karaite congregations were registered as Turks, some of them retained Jewish customs. In the 1990s, many Karaites emigrated to Israel, under the Law of Return.[115][116] The largest Karaite community has since then resided in Israel.

Igbo Jews

Igbo people of Nigeria who practice a form of Judaism are referred to as Igbo Jews. Judaism has been documented in parts of Nigeria since the precolonial period, from as early as the 1500s, but is not known to have been practiced in the Igbo region in precolonial times. Nowadays, up to 30,000 Igbos are practicing some form of Judaism.[117]

Subbotniks

The Subbotniks are a movement of Jews of Russian ethnic origin which split off from other Sabbatarians in the late 18th century. The majority of the Subbotniks practiced Rabbinic and Karaite Judaism, a minority of them practiced Spiritual Christianity.[118][119] Subbotnik families settled in the Holy Land which was then a part of the Ottoman Empire, in the 1880s, as part of the Zionist First Aliyah in order to escape oppression in the Russian Empire and later, most of them married other Jews. Their descendants included Israeli Jews such as Alexander Zaïd, Major-General Alik Ron,[120] and the mother of Ariel Sharon.[121]

20th/21st-century movements

20th-century movements

Additionally, a number of smaller groups have emerged:

A type of Judaism that is predominantly practiced in African communities, both inside and outside Africa (such as North America). It is theologically characterized by the selective acceptance of the Judaic faith (in some cases, such selective acceptance has historical circumstances), and the belief system of Black Judaism is significantly different from the belief system of the mainstream movements of Judaism. In addition, although Black Judaic communities adopt Judaic practices such as the celebration of Jewish holidays and the recital of Jewish prayers, some of them are generally not considered legitimate Jews by mainstream Jewish societies.[122][123]

Rather than a type, Judaism as practiced by the

Formed in the early 20th century by Alfred G. Moses and Morris Lichtenstein, Jewish Science was founded as a counterweight Jewish movement to Christian Science. Jewish Science sees God as a force or energy penetrating the reality of the Universe and emphasis is placed upon the role of affirmative prayer in personal healing and spiritual growth. The Society of Jewish Science in New York is the institutional arm of the movement regularly publishing The Interpreter, the movement's primary literary publication.[130]

Founded by rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, the 1922 American split from Conservative Judaism that views Judaism as a progressively evolving civilization with focus on Jewish community.[11][131][132][133][106][134] The central organization is "Reconstructing Judaism". Assessments of its impact range from being recognized as the 4th major stream of Judaism[11][131][132][135][16] to described as a smaller movement.[136] As noted, Reconstructionism is a smaller movement, but its ideas significantly impacted Jewish life in the America.[15][137]

A nontheistic worldwide movement that emphasizes Jewish culture and history as the sources of Jewish identity. Originated in Detroit in 1963 with the founding figure, Reform rabbi Sherwin Wine, in 1969 was established the Society for Humanistic Judaism.[138][139]

The

Partly syncretistic movement founded in the mid-1970s by ex-Lubavich's Hasidic rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi and rooted in the counterculture of the 1960s and the Havurat Shalom group. The "Bnei ʻOr" (Songs of Light) in Philadelphia—the first Renewal community—later was established the ambrella organisation "ALEPH: the Alliance for Jewish Renewal". Its syncretism includes Kabbalah, neo-Hasidism, Reconstructionist Judaism, Western Buddhist meditation, Sufism, New Age, feminism, liberalism, and so on, tends to embrace the ecstatic worship style. Renewal congregations tend to be inclusive on the subject of who is a Jew and had avoided affiliation with any Jewish communities.[140][142]

The term is occasionally applied to describe either individuals or new congregations, especially congregations which were established in the US in 1984 by rabbi David Weiss Halivni, such as the Union for Traditional Judaism, located between the Conservative and Modern Orthodox.[143][144] While most scholars consider "Union for Traditional Judaism" (formerly Union for Traditional Conservative Judaism) as a new movement, some attribute it to the right wing of Conservative Judaism.[145]

A "New Age Judaism"[146] worldwide organisation established in 1984 by American rabbi Philip Berg, that popularizes Jewish mysticism among a universal audience.[147][148]

A Haredi sect formed in the 1980s by Israeli-Canadian rabbi Shlomo Helbrans, follows a strict version of halakha, including its own unique practices such as lengthy prayer sessions, arranged marriages between teenagers, and head-to-toe coverings for females.[149]

A movement founded by Avi Weiss in the late 1990s in US, with its own schools for religious ordination, both for men (Yeshivat Chovevei Torah) and women (Yeshivat Maharat). The movement declarates liberal, or inclusive Orthodoxy with women's ordination, full accepting LGBT members, and reducing stringent rules for conversion.[150]

A controversial ultra-Orthodox group with a Jewish burqa-style covering of a woman's entire body, including a veil covering the face.[151] Also known as the "Taliban Women" and the "Taliban Mothers" (נשות הטאליבן).[152]

Made up of followers who seek to combine parts of Rabbinic Judaism with a belief in Jesus as the Messiah and other

Remark: Baal teshuva movement—a description of the return of secular Jews to religious Judaism and involved with all the Jewish movements.

Trans- and post-denominational Judaism

Already in the 1980s, 20–30 percent of members of the largest American Jewish communities, such as of New York City or Miami, rejected a denominational label.[158] And "Israeli Democracy Index" commissioned in 2013 by the Israel Democracy Institute found that the two thirds of respondents said they felt no connection to any denomination, or declined to respond.[159]

The very idea of Jewish denominationalism is contested by some Jews and Jewish non-denominational organisations, which consider themselves to be "trans-denominational" or "post-denominational".[160][142][161][162][163] The term "trans-denominational" also applied to describe new movements located on the religious continuum between some major streams, as an instance, Conservadox (Union for Traditional Judaism).[143][144]

A variety of new Jewish organisations are emerging that lack such affiliations:

- Havurah movement is the number of small egalitarian experimental spiritual groups (first in 1960 in California) for prayer as autonomous alternatives to Jewish movements. Most notable of them is the Havurat Shalom in Somerville, Massachusetts;[142]

- Independent minyan movement is a lay-led Jewish worship and study community that has developed independently of established denominational and synagogue structures and combines halakha with egalitarianism;[164]

- International Federation of Rabbis (IFR), a non-denominational rabbinical organization for rabbis of all movements and backgrounds;[162]

- Some Jewish day schools lack affiliation with any one movement;[165][162]

- There are several seminaries which are not controlled by a denomination (see List of rabbinical schools § Non-denominational and Rabbi § Seminaries unaffiliated with main denominations):

- Academy for Jewish Religion (California) (AJRCA) is a transdenominational seminary based in Los Angeles, California. It draws faculty and leadership from all denominations of Judaism. It has programs for rabbis, cantors, chaplains, community leadership and Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE);[162]

- Academy for Jewish Religion (New York) (AJR) is a transdenominational seminary in Yonkers, NY, that trains rabbis and cantors and also offers Master's Program in Jewish Studies;[citation needed]

- Hebrew College, a seminary in Newton Centre, Massachusetts, near Boston;[162]

- Hebrew Seminary in Skokie, Illinois[citation needed]

- Other smaller, less traditional institutions include:[166]

- Rimmon Rabbinical School

- Mesifta Adath Wolkowiskaimed at community professionals with significant knowledge and experience.

Organizations such as these believe that the formal divisions that have arisen among the "denominations" in contemporary Jewish history are unnecessarily divisive, as well as religiously and intellectually simplistic. According to Rachel Rosenthal, "the post-denominational Jew refuses to be labeled or categorized in a religion that thrives on stereotypes. He has seen what the institutional branches of Judaism have to offer and believes that a better Judaism can be created."[167] Such Jews might, out of necessity, affiliate with a synagogue associated with a particular movement, but their own personal Jewish ideology is often shaped by a variety of influences from more than one denomination.

Bnei Noah

List of contemporary movements

- Orthodox Judaism

- Haredi Judaism (ultra-Orthodox)

- Hasidic Judaism

- Hasidic dynasties

- Belz

- Bobov

- Breslov

- Chabad-Lubavitch

- Ger

- Karlin-Stolin

- Sanz-Klausenburg

- Satmar

- Shomer Emunim

- Skver

- Vizhnitz

- Other dynasties

- Misnagdim (Lita'im, Lithuanian)

- Sephardic Haredim

- Dor Daim

- Other Haredim

- Hasidic Judaism

- Modern Orthodox Judaism

- Haredi Judaism (ultra-Orthodox)

- Conservative Judaism (Masorti)

- Reform Judaism

- Other Rabbinic

- Non-Rabbinic

See also

- Genetic studies on Jews

- Groups claiming affiliation with Israelites

- Jewish diaspora

- Jewish prayer

- Jewish schisms

- Jewish views on religious pluralism

- List of religious organizations#Jewish organizations

- Who is a Jew?

Notes

- ^ "Messianic Judaism is a Protestant movement that emerged in the last half of the 20th century among believers who were ethnically Jewish but had adopted an Evangelical Christian faith… By the 1960s, a new effort to create a culturally Jewish Protestant Christianity emerged among individuals who began to call themselves Messianic Jews."[155]

References

- ^ ISBN 0-23108-668-7.

- ^ ISBN 1-59244-943-3.

- ^ a b c d Tabory, Ephraim (2004). "The Israel Reform and Conservative Movements and the Marker for the Liberal Judaism". In Rebhum, Uzi; Waxman, Chaim I. (eds.). Jews in Israel: Contemporary Social and Cultural Patterns. Brandeis University Press. pp. 285–314.

- ^ Deshen, Liebman & Shokeid 2017, Ch. 18 "Americans in the Israeli Reform and Conservative Denominations".

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-975927-9.

- ^ Deshen, Liebman & Shokeid 2017, pp. 33–62, Ch. 3 "Demensions of Jewish Religiosity".

- ^ ISBN 9780300129106.

- ^ a b Philipson, David (1907). The Reform Movement in Judaism. London; New York: Macmillan. Archived from the original on 2009-06-16.

- ^ ISBN 0819144800.

- ISBN 0-87441-286-2.

- ^ ISBN 0870682792.

- ISBN 978-0-8276-0892-4.

- ^ ISBN 9780195051674.

- ISBN 0-8147-9261-8.

- ^ ISBN 0-8160-5457-6.

- ^ ISBN 9780787666118 – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4 – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ ISBN 9780791492024.

- ISBN 0-664-25348-2.

- ISBN 978-0-691-18129-5.

- ISBN 978-1-56000-178-2.

- ISBN 978-0-7914-3581-6.

- ISBN 978-606-072-000-3.

- ]

- ISBN 0-06066801-6.

- ^ Wertheimer 2018, p. 103.

- ^ Neusner 1975, "The Orthodox stream".

- ^ ISBN 9780191726446.

- ^ Neusner 1975, "Orthodox sectarians".

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8143-3953-4.

- ^ ISBN 9780191726446.

- ^ ISBN 9780881258134.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-567-05161-5.

- ISBN 0-391-04143-6.

- ^ "Rabbinic Judaism". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- S2CID 162698361.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kohler, Kaufmann; Harkavy, Abraham de (1901–1906). "Karaites and Karaism". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kohler, Kaufmann; Harkavy, Abraham de (1901–1906). "Karaites and Karaism". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ISBN 978-0-9700775-4-7.

- ISBN 978-0-19-975927-9.

- ^ a b c Rudavsky 1979, pp. 50–78.

- ^ ISBN 0-88125-031-7.

- ISBN 0-8147-9705-9.

- ^ a b Weiner, Rebecca. "Judaism: Sephardim". Jewish Virtual Library. A Project of AICE. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ Meyer 1988, pp. 232–235.

- ^ ISBN 9-78-0-415-26707-6.

- JSTOR 41482436.

- ^ Deshen, Liebman & Shokeid 2017, Part 5 "The Sephardic Pattern".

- ^ Simon, Reeva; Laskier, Michael; Reguer, Sara, eds. (2002). The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa In Modern Times. New York: Columbia University Press, s.v. Ch. 8 and 21.

- ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- ^ Rudavsky 1979, pp. 116–155.

- ^ ISBN 0-8147-9261-8.

- ISBN 9780191726446.

- YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

- ^ a b [Telushkin, Joseph]. "Orthodox Judaism: Hasidim and Mitnagdim". Jewish Virtual Library. A Project of AICE. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- ^ Rudavsky 1979, pp. 135–139.

- ISBN 9780801861826.

- YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- ISBN 9780191726446.

- ^ Karz, Dov (1977). The Musar Movement: Its History, Leading Personalities, and Doctrines. Vol. 1. Translated by Leonard Oschry. Tel Aviv: Orly Press.

- ^ Bacon, Gershon C. (2005). "Musar Movement". In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion: 15-volume Set (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, Mi: Macmillan Reference USA – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ISBN 9780191726446.

- YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ Lazerwitz et al. 1998, pp. 15–24.

- ^ Rudavsky 1979, pp. 98–115.

- ^ Rudavsky 1979, pp. 218–270, 367–402.

- ^ Raphael 1984, pp. 125–176.

- ISBN 1-57718-058-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ISBN 0-8173-0485-1.

- ^ a b Wertheimer 2018, pp. 67–100, 143–159.

- ^ Schweid, Eliezer (1984–1985). "Two Neo-Orthodox Responses to Secularization. Part I: Samson Raphael Hirch" (PDF). Immanuel (19). Translated by Yohanan Eldad: 107–117. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-05. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- ISSN 0196-7053.

- ISBN 9780765799531.

- ^ Rudavsky 1979, pp. 156–185, 285–316.

- ^ Raphael 1984, pp. 1–78.

- ISBN 1-59244-943-3.

- ISBN 1-57718-058-5.

- ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- ISBN 0-8160-5457-6.

- ISBN 9780815300762.

- ISBN 9781461940500.

- ^ ISBN 0-8135-2821-6.

- ^ Wertheimer 2018, pp. 103–120.

- ^ Rudavsky 1979, pp. 186–217.

- ^ Wertheimer 2018, pp. 121–142.

- ^ Rudavsky 1979, pp. 317–346.

- ^ Raphael 1984, pp. 79–124.

- ISBN 0-87441-547-0.

- ISBN 1-57718-058-5.

- ISBN 978-0-19-975927-9.

- ^ a b Syme, Daniel B. (1988). The Jewish Home: A Guide for Jewish Living. URJ Press. ISBN 0874419883.

- ^ a b Donin, Hayim Halevy (1972). To Be a Jew: A Guide to Jewish Observance in Contemporary Life. Basic Books. ISBN 1541674022.

- ^ Roden, Claudia (1996). The Book of Jewish Food: An Odyssey from Samarkand to New York. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-53258-9.

- ^ Johnson, Paul (1987). A History of the Jews. Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-091533-1.

- ^ Hazony, Yoram (2000). The Jewish State: The Struggle for Israel's Soul. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-02966-3.

- ^ Kushner, Lawrence (2001). Jewish Spirituality: A Brief Introduction for Christians. Jewish Lights Publishing. ISBN 1580231500.

- ^ Morinis, Alan (2007). Everyday Holiness: The Jewish Spiritual Path of Mussar. Trumpeter. ISBN 1590306090.

- OCLC 9686985.

- ^ Ticker, Jay (1975). The Centrality of Sacrifices as an Answer to Reform in the Thought of Zvi Hirsch Kalischer. Working Papers in Yiddish and East European Studies, vol. 15. New York: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

- ^ ISBN 1-59244-943-3.

- ^ ISBN 1-59244-943-3.

- ^ ISBN 0-226-70577-3.

- ^ Deshen, Liebman & Shokeid 2017, Part 4 "Nationalist Orthodoxy".

- ISBN 978-1-60280-022-9.

- ^ ISBN 0-8160-5457-6.

- ^ Deshen, Liebman & Shokeid 2017, Ch. 10 "Religious Kibbutzim: Judaism and Modernization".

- ^ ISBN 9780826411778– via Myjewishlearning.com.

- ISBN 0-664-25348-2.

- OCLC 44759291.

- OCLC 179259677.

- ISBN 978-0-19-975927-9.

- ^ "Are American Jews the New Secret Jews? Interview with Rabbi Jacques Cukierkorn". Chicago Jewish Cafe. 2018-10-03. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ^ "Beta Israel". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ Kizilov, Mikhail. "Karaites and Karaism: Recent Developments". Religion and Democracy: An Axchange of Experiences between East and West. The CESNUR 2003 International Conference organized by CESNUR, Center for Religious Studies and Research at Vilnius University, and New Religions Research and Information Center. Vilnius, Lithuania, April 9–12, 2003. CESNUR.

- ^ Moroz, Eugeny (2004). "От иудаизма к тенгрианству. Ещё раз о духовных поисках современных крымчаков и крымских караимов»" [From Judaism to Tengrism. Once again about the spiritual quest of the contemporary Krymchaks and Crimean Karaites]. Народ Книги в мире книг [People of the Book in the world of books] (in Russian) (52): 1–6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-533356-5. p. 143.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rosenthal, Herman; Hurwitz, S. (1901–1906). "Subbotniki ("Sabbatarians")". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rosenthal, Herman; Hurwitz, S. (1901–1906). "Subbotniki ("Sabbatarians")". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ISBN 9780814335970. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-10.

- ^ Weiss, Ruchama; Brackman, Levi (December 9, 2010). "Russia's Subbotnik Jews get rabbi". Israel Jewish Scene. Archived from the original on 2021-05-01. Retrieved 2015-08-22.

- ^ Eichner, Itamar (March 11, 2014). "Subbotnik Jews to resume aliyah". Israel Jewish Scene. Archived from the original on 2014-04-09. Retrieved 2014-04-09.

- ^ Bruder 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-89089-820-8.

- ^ Maltz, Judy (2020-01-05). "In First, a Ugandan-Jewish Wedding in Israel". Haaretz. Retrieved 2020-01-07.

- ^ "Over 250 Africans convert to Judaism in Uganda", Jerusalem Post, July 16, 2008[permanent dead link]

- ^ http://fr.jpost.com/servlet/Satellite?cid=1215331079553&pagename=JPost/JPArticle/ShowFull[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kestenbaum, Sam (2016-02-27) [last updated April 10, 2018]. "Rabbi From Tiny Ugandan Jewish Community Wins Seat in Parliament". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2021-01-26.

- ^ The Abayuday:Judaism Emerging, A Spiritual Journey Into Africa, by Menachem Kuchar.

- ^ The Committee To Save Ugandan Jewry - A First Hand Account of The History of the Abayudaya Archived 2007-12-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 0-19-504400-2.

- ^ a b Rudavsky 1979, pp. 347–366.

- ^ a b Raphael 1984, pp. 177–194.

- ISBN 9780815300786.

- ^ Alpert, Rebecca (2011). "Judaism, Reconstructionist". The Cambridge Dictionary of Judaism and Jewish Culture. Cambridge University Press. p. 346.

- ^ Mittleman 1993, p. 169.

- ^ Niebuhr, Gustav (January 18, 1997). "A Jewish Movement Takes Stock of Itself at Age 40". The New York Times.

- ^ Liebman, Charles S. (1970). "Reconstructionism in American Jewish Life" (PDF). American Jewish Year Book: 3–99.

- ISBN 0-8160-5457-6.

- ISBN 9-78-0-415-26707-6.

- ^ ISBN 0-02-865740-3.

- ISBN 9780253008022.

- ^ a b c Magid 2013.

- ^ a b Ament, Jonathon (2004). The Union for Traditional Judaism: A Case Study of Contemporary Challenges to a New Religious Movement (PhD thesis). Waltham, Mass.: Department of Near Eastern and Jewish Studies, Brandeis University.

- ^ a b Michaelson, Jay (October 13, 2006). "Old Labels Feel Stiff for 'Flexidox'". The Jewish Daily Forward. Archived from the original on 2006-10-18.

- ^ Lazerwitz et al. 1998, p. 24.

- ISBN 1-57718-058-5.

- ISBN 9-78-0-415-26707-6.

- ISBN 978-0-275-98940-8.

- ^ Fogelman, Shay (March 9, 2012). "Lev Tahor: Pure as the driven snow, or hearts of darkness?". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2014-05-17. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

- The New York Jewish Week. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- ^ "A Jewish Movement to Shroud the Female Form". NPR. March 17, 2008. Archived from the original on July 29, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Novick, Akiva (February 6, 2011). "'Taliban women': A cover story". Ynetnews.com.

- ISBN 9780761989523.

- ISBN 978-0-8264-5458-4.

- ISBN 0-8160-5456-8.

- ^ "Israeli Court Rules Jews for Jesus Cannot Automatically Be Citizens". The New York Times. December 27, 1989. Archived from the original on 2008-05-23. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ISBN 9-78-0-415-26707-6. p. 399.

- ^ Wertheimer 1991, pp. 86–88.

- ^ Ettinger, Yair (June 11, 2013). "Poll: 7.1 Percent of Israeli Jews Define Themselves as Reform or Conservative". Haaretz. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- ^ Ferziger 2012, Lesson 10. Beyond Denominationalism.

- ^ Heilman, Uriel (February 11, 2005). "Beyond Dogma". The Jerusalem Post.

- ^ ISBN 9781543470857.

- ^ Wertheimer 2018, pp. 160–180.

- ^ Salmon, Jackquelin L. (June 6, 2009). "New Judaism". The Washington Post.

- The Jewish Week.

- ^ Lobel, Andrea (2021). "A Different Path to Ordination". Tablet.

- ^ Rosenthal, Rachel (2006). "What's in a name?". Kedma (Winter).

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; Greenstone, Julius H. (1901–1906). "Noachian Laws". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; Greenstone, Julius H. (1901–1906). "Noachian Laws". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ Feldman, Rachel Z. (October 8, 2017). "The Bnei Noah (Children of Noah)". World Religions and Spirituality Project. Archived from the original on 2020-01-21. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

- Project MUSE.

Further reading

- ISBN 9789004105836.

- ISBN 978-002-865-928-2.

External links

- Neusner, Jacob; et al. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Judaism Online.

- Emergence of Jewish Denominations (MyJewishLearning.com)

- Jewish World Today. Overview: State of the Denominations (MyJewishLearning.com)

- Jewing Movements - How Jewish movements will and have evolved

- Orthodox/Haredi

- Orthodox Judaism – The Orthodox Union

- Chabad-Lubavitch

- Rohr Jewish Learning Institute

- The Various Types of Orthodox Judaism Archived 2005-11-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Aish HaTorah

- Ohr Somayach

- Traditional/Conservadox

- Conservative

- The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism

- Masorti (Conservative) Movement in Israel

- United Synagogue Youth

- Reform/Progressive

- The Union for Reform Judaism (USA)

- Reform Judaism (UK)

- Liberal Judaism (UK)

- World Union for Progressive Judaism (Israel)

- Reconstructionist

- Renewal

- Humanistic

- Karaite