Johannes Oporinus

This article includes a improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (August 2022) ) |

Johannes Oporinus | |

|---|---|

classical philology | |

| Institutions | University of Basel |

Johannes Oporinus (also Johannes Oporin; Latinised from the original German name: Johannes Herbster or Hans Herbst) (25 January 1507 – 7 July 1568) was a humanist printer in Basel.

Life

Johannes Oporinus, the son of the painter Hans Herbst, was born in Basel.[1] He completed his academic training in Strasbourg and Basel. After working as a teacher in the Cistercian convent of St. Urban,[2] he returned to Basel, where he taught at the school of Leonhard.[2] In Basel, he enrolled into the University of Basel, where he studied law under Bonifacius Amerbach and Hebrew with Thomas Platter.[2] Concordantly he worked as a proofer in the workshop of Johann Froben, the most important printer of Basel the early 16th Century. In addition, he taught at the Basel Latin school from 1526. In 1527 he was temporarily famulus to the physician Paracelsus.[1]

From 1538, Oporinus was the professor for Greek and Latin at the University of Basel.[1] In 1542 he resigned his academic post to devote himself full-time to his printing workshop.[1] In addition, he completed a medical studies. In 1567, he sold his printshop to the Gemuseus family. Theodor Zwinger

Publications

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

He published a Latin version of the Gesta Danorum in 1534, entitled Saxonis grammatici Danorum historiae libri XVI.

In 1542, he attempted to print the first

The most important publication of his workshop was the anatomical atlas

In addition, his press published numerous polemical theological works, classics, and historiographical works. His fine knowledge of ancient languages served the quality of consistently correct textual editions. Oporinus later printed a work on church history by

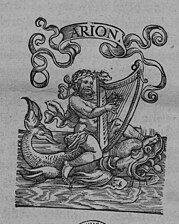

Oporinus' mark

Looking at title page or at the colophon of an Oporinus edition, the printer's device shows the mythological lyre player Arion of Lesbos, which is supported by a Dolphin on the sea. There are more variant forms of it, some are shown below.

Personal life

He was born to Hans Herbst (also spelled Herbster) and Barbara Lupfart.[2] His father was a painter from Strasbourg and lost most of his work with the reformation.[6] He was married four times, each time with a widow. The third wife was a sister of the publisher Johan Hervagius the younger (died 1564)[7] and the fourth a sister of Basilius Amerbach.[1] He died deeply in debt on the 7 July 1568 and all his possessions were confiscated by the authorities in order to pay his creditors.[8] Theodor Zwinger was his nephew.[9] He had an extensive library of 4000 books, which was auctioned.[9] His manuscript collection and his extensive correspondence are preserved in the Basel University Library.[citation needed]

References

- ^ ISBN 3-7643-1173-8.

- ^ a b c d "Johannes Oporinus". University of Basel. Retrieved 2022-12-10.

- ^ James Kritzeck (1964), Peter the Venerable and Islam (Princeton University Press), pp. vii–viii.

- ^ Kusukawa, Sachiko. "De humani corporis fabrica. Epitome". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ a b Gilly, Carlos (2001).pp.18–19

- ^ Gilly, Carlos (2001),p.7

- ^ Klemm, Heinrich (1884). Beschreibender catalog des Bibliographischen museums. Getty Research Institute. Dresden, H. Klemm. pp. 232–233.

- ^ Gilly, Carlos (2001). Die Manuskripte in der Bibliothek des Johannes Oporinus (in German). Basel: Schwabe Verlag. p. 9.

- ^ a b Gilly, Carlos (2001).p.10

Further reading

- Harry Clark (1984), The Publication of the Koran in Latin: A Reformation Dilemma. The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol.15, No.1, (Spring 1984), pp. 3–12. Available via JSTOR

- Carlos Gilly (2001), Die Manuskripte in der Bibliothek des Johannes Oporinus: Verzeichnis der Manuskripte und Druckvorlagen aus dem Nachlass Oporins anhand des von Theodor Zwinger und Basilius Amerbach erstellten Inventariums. (Schriften der Universitätsbibliothek Basel 3). Schwabe, Basel, ISBN 3-7965-1088-4

- Martina Hartmann (2001), Humanismus und Kirchenkritik. Matthias Flacius Illyricus als Erforscher des Mittelalters. (Beiträge zur Geschichte und Quellenkunde des Mittelalters 19) Thorbecke, Stuttgart, ISBN 3-7995-5719-9

- Martina Hartmann, Arno Mentzel-Reuters (2005), Die Magdeburger Centurien und die Anfänge der quellenbezogenen Geschichtsforschung. Ausstellung. Monumenta Germaniae Historica (MGH), Munich.

- Andreas Jociscus (1569) Oratio De Ortv, Vita, Et Obitv Ioannis Oporini Basiliensis, Typographicoru[m] Germaniæ Principis. Rihelius, Strasbourg (digitized, also contains the Catalogvs Librorvm Per Ioannem Oporinium excusorum)

- Oliver K. Olson (2002) Matthias Flacius and the survival of Luther’s Reform. (Wolfenbütteler Abhandlungen zur Renaissanceforschung 20). Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel, ISBN 3-447-04404-7

- Karl Steiff (1887), "Oporinus, Johannes", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 24, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 381–387

- Martin Steinmann (1967) Johannes Oporinus. Ein Basler Buchdrucker um die Mitte des 16. Jahrhunderts. (Basler Beiträge zur Geschichtswissenschaft 105). Helbing & Lichtenhahn, Basel.

- Martin Steinmann (1969), Aus dem Briefwechsel des Basler Druckers Johannes Oporinus. Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde 69 (1969): 104–203

External links

- Sample pages from Vesalius' De humani corporis fabrica

- Digitized Magdeburg Centuries

- Oporinus, Johannes in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Digital edition of De humani corporis fabrica; Epitome published by Oporinus in 1543, in Cambridge Digital Library