John II of France

| John II | |

|---|---|

Saint Denis Basilica | |

| Spouses | |

| Issue |

|

| House | Valois |

| Father | Philip VI of France |

| Mother | Joan of Burgundy |

| Signature |  |

John II (

While John was a prisoner in London, his son

Early life

John was nine years old when his father, Philip VI, was crowned king. Philip VI's ascent to the throne was unexpected: all three sons of Philip IV had died without sons and their daughters were passed over. Also passed over was King Edward III of England, Philip IV's grandson through his daughter, Isabella. Thus, as the new king of France, John's father Philip VI had to consolidate his power in order to protect his throne from rival claimants; therefore, he decided to marry off his son John quickly at the age of thirteen to form a strong matrimonial alliance.

Search for a wife and first marriage

Initially a marriage with

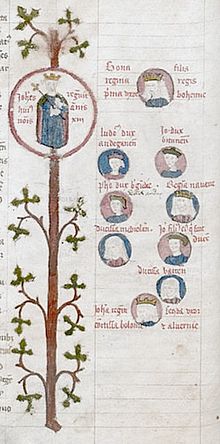

John reached the age of majority, 13 years and one day, on 27 April 1332, and received the Duchy of Normandy, as well as the counties of Anjou and Maine.[1] The wedding was celebrated on 28 July at the church of Notre-Dame in Melun in the presence of six thousand guests. The festivities were prolonged by a further two months when the young groom was finally knighted at the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris. As the new duke of Normandy, John was solemnly granted the arms of a knight in front of a prestigious assembly bringing together the kings of Bohemia and Navarre, and the dukes of Burgundy, Lorraine and Brabant.

Duke of Normandy

Accession and rise of the English and the royalty

Upon his accession as Duke of Normandy in 1332, John had to deal with the reality that most of the Norman nobility was already allied with the English. Effectively, Normandy depended economically more on maritime trade across the English Channel than on river trade on the Seine. Although the duchy had not been in Angevin possession for 150 years, many landowners had holdings across the Channel. Consequently, to line up behind one or other sovereign risked confiscation. Therefore, Norman members of the nobility were governed as interdependent clans, which allowed them to obtain and maintain charters guaranteeing the duchy a measure of autonomy. It was split into two key camps, the counts of Tancarville and the counts of Harcourt, which had been in conflict for generations.[2]

Tension arose again in 1341. King Philip, worried about the richest area of the kingdom breaking into bloodshed, ordered the

Meeting with the Avignon Papacy and the King of England

In 1342, John was in

Relations with Normandy and rising tensions

By 1345, increasing numbers of Norman rebels had begun to pay homage to Edward III, constituting a major threat to the legitimacy of the Valois kings. The defeat at the

Black Death and second marriage

On 11 September 1349, John's wife, Bonne of Bohemia (Bonne de Luxembourg), died at the Maubuisson Abbey near Paris, of the Black Death, which was devastating Europe. To escape the pandemic, John, who was living in the Parisian royal residence, the Palais de la Cité, left Paris.

On 9 February 1350, five months after the death of his first wife, John married Joan I, Countess of Auvergne, in the royal Château de Sainte-Gemme (which no longer exists), at Feucherolles, near Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

King of France

Coronation

Philip VI, John's father, died on 22 August 1350, and John's coronation as John II, king of France, took place in Reims the following 26 September. Joanna, his second wife, was crowned queen of France at the same time.[7]

In November 1350, King John had Raoul II of Brienne, Count of Eu seized and summarily executed,[8] for reasons that remain unclear, although it was rumoured that he had pledged the English the County of Guînes for his release.

In 1354, John's son-in-law and cousin,

The following year, on 10 September 1355 John and Charles signed the

This act, which was largely driven by revenge for Charles of Navarre's and John of Harcourt's pre-meditated plot that killed John's favorite, Charles de La Cerda, would push much of what remaining support the King had from the lords in Normandy away to King Edward and the English camp, setting the stage for the English invasion and the resulting Battle of Poitiers in the months to come.

Battle of Poitiers

In 1355, the

John was confident of victory—his army was probably twice the size of his opponent's—but he did not immediately attack. While he waited, the papal legate went back and forth, trying to negotiate a truce between the leaders. There is some debate over whether the Black Prince wanted to fight at all. He offered his wagon train, which was heavily loaded with loot. He also promised not to fight against France for seven years. Some sources claim that he even offered to return Calais to the French crown. John countered by demanding that 100 of the Prince's best knights surrender themselves to him as hostages, along with the Prince himself. No agreement could be reached. Negotiations broke down, and both sides prepared for combat.

On the day of the battle, John and 17 knights from his personal guard dressed identically. This was done to confuse the enemy, who would do everything possible to capture the sovereign on the field. In spite of this precaution, following the destruction and routing of the massive force of French knights at the hands of the ceaseless English longbow volleys, John was captured as the English force charged to finish their victory. Though he fought with valor, wielding a large battle-axe, his helmet was knocked off. Surrounded, he fought on until Denis de Morbecque, a French exile who fought for England, approached him.

"Sire," Morbecque said. "I am a knight of Artois. Yield yourself to me and I will lead you to the Prince of Wales."

Surrender and capture

King John surrendered by handing him his glove. That night King John dined in the red silk tent of his enemy. The Black Prince attended to him personally. He was then taken to Bordeaux, and from there to England. The Battle of Poitiers would be one of the major military disasters not just for France, but at any time during the Middle Ages.

While negotiating a peace accord, John was at first held in the Savoy Palace, then at a variety of locations, including Windsor, Hertford, Somerton Castle in Lincolnshire, Berkhamsted Castle in Hertfordshire, and briefly at King John's Lodge, formerly known as Shortridges, in East Sussex. Eventually, John was taken to the Tower of London.

Prisoner of the English

As a prisoner of the English, John was granted royal privileges that permitted him to travel about and enjoy a regal lifestyle. At a time when law and order was breaking down in France and the government was having a hard time raising money for the defence of the realm, his account books during his captivity show that he was purchasing horses, pets, and clothes while maintaining an astrologer and a court band.

Treaty of Brétigny

The Treaty of Brétigny (drafted in May 1360) set his ransom at an astounding 3 million crowns, roughly two or three years worth of revenue for the French Crown, which was the largest national budget in Europe during that period. On 30 June 1360 John left the Tower of London and proceeded to Eltham Palace where Queen Philippa had prepared a great farewell entertainment. Passing the night at Dartford, he continued towards Dover, stopping at the Maison Dieu of St Mary at Ospringe, and paying homage at the shrine of St Thomas Becket at Canterbury on 4 July. He dined with the Black Prince—who had negotiated the Treaty of Brétigny[11]—at Dover Castle, and reached English-held Calais on 8 July.[12]

Leaving his son Louis of Anjou in Calais as a replacement hostage to guarantee payment, John was allowed to return to France to raise the funds. The Treaty of Brétigny was ratified in October 1360.

Louis' escape and returning to England

On 1 July 1363, King John was informed that Louis had broken his parole and escaped from Calais. Troubled by the dishonour of this action, and the arrears in his ransom, John gathered his royal council to announce that he would voluntarily return to captivity in England and negotiate with Edward in person.[13][14] When faced with the opposition of his advisors, the king famously replied that "if good faith were banned from the Earth, she ought to find asylum in the hearts of kings".[15] Immediately after he appointed his son Charles the Duke of Normandy to be regent and governor of France until his return.[16]

Death

John landed in England in January 1364 where he was met by Sir

Personality

Physical strength

John suffered from fragile health. He engaged little in physical activity, practised jousting rarely, preferring hunting.[18] Contemporaries report that he was quick to get angry and resort to violence, leading to frequent political and diplomatic confrontations. He enjoyed literature and was patron to painters and musicians.

Image

The image of a "warrior king" probably emerged from the courage he displayed at the Battle of Poitiers, where he dismounted to fight in the forefront of his surrounded men with a poleaxe in his hands,[19] as well as the creation of the Order of the Star. This was guided by political need, as John was determined to prove the legitimacy of his crown, particularly as his reign, like that of his father, was marked by continuing disputes over the Valois claim from both Charles II of Navarre and Edward III of England. From a young age, John was called to resist the decentralising forces affecting the cities and the nobility, each attracted either by English economic influence or the reforming party. He grew up among intrigue and treason, and in consequence he governed in secrecy only with a close circle of trusted advisers.

Personal relationships

He took as his wife

Ancestry

| Ancestors of John II of France |

|---|

| French monarchy |

| Capetian dynasty (House of Valois) |

|---|

|

| Philip VI |

|

| John II |

| Charles V |

|

| Charles VI |

| Charles VII |

|

|

Louis XI |

|

| Charles VIII |

Issue

On 28 July 1332, at the age of 13, John was married to

- Charles V of France (21 January 1338 – 16 September 1380)[27]

- Catherine (1338–1338) died young

- Louis I, Duke of Anjou (23 July 1339 – 20 September 1384), married Marie of Blois[27]

- John, Duke of Berry (30 November 1340 – 15 June 1416), married Jeanne of Auvergne[27]

- Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (17 January 1342 – 27 April 1404), married Margaret of Flanders[27]

- Joan (24 June 1343 – 3 November 1373), married Charles II (the Bad) of Navarre[27]

- Robert I, Duke of Bar[28]

- Agnes (9 December 1345 – April 1350)

- Margaret (20 September 1347 – 25 April 1352)

- Gian Galeazzo I, Duke of Milan[29]

On 19 February 1350, at the royal Château de Sainte-Gemme, John married

- Blanche (b. November 1350)

- Catherine (b. early 1352)

- a son (b. early 1353)

Succession

John II was succeeded by his son, Charles, who reigned as Charles V of France, known as The Wise.

References

- ^ François Autrand (1994). Charles V le Sage. Paris: Fayard. p. 13.

- ^ Autrand, Françoise, Charles V, Fayard, Paris, 1994, 153.

- ^ Favier, Jean, La Guerre de Cent Ans, Fayard, Paris, 1980, p. 140

- ^ Papal Coronations in Avignon, Bernard Schimmelpfennig, Coronations: Medieval and Early Modern Monarchic Ritual, ed. János M. Bak, (University of California Press, 1990), pp. 191–192.

- ^ Sumption, Jonathan, Trial by Battle: The Hundred Years War I, Faber & Faber, 1990, p. 436.

- ^ Autrand, Françoise, Charles V, Fayard, Paris, 1994, p. 60

- ^ Anselme de Sainte-Marie, Père (1726). Histoire généalogique et chronologique de la maison royale de France [Genealogical and chronological history of the royal house of France] (in French). Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). Paris: La compagnie des libraires. p. 105.

- ^ Jones, Michael. "The last Capetians and early Valois Kings, 1314–1364", Michael Jones, The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 6, c. 1300 – c. 1415, (Cambridge University Press, 2000), 391.

- ISBN 2-213-02769-2.

- ^ Borel d’Hauterive, André. Notice Historique de la Noblesse (Tome 2 ed.). p. 391.

- ^ Hunt, William (1889). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 17. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 90–101. , citing Fœdera, iii, 486; Chandos, l. 1539

- ^ Stanley, Arthur Penrhyn (1906). Historical Memorials of Canterbury. London: J. M. Dent & Co. pp. 234, 276–279.

- ^ Autrand, Françoise, Charles V, Fayard, Paris, 1994, p. 446.

- ISBN 9780199651702. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Bouillet, Marie-Nicolas, Dictionnaire universel d'histoire et de géographie, Librairie Hachette, Paris, 1878, p. 954.

- ^ Jean Froissart, Chronicles, translator Geoffrey Brereton, Penguin Classics, Baltimore, 1968, p. 167.

- ^ Jean Froissart, Chronicles, translator Geoffrey Brereton, Penguin Classics, Baltimore, 1968, p. 168.

- ^ Autrand, Françoise, Charles V, Fayard, Paris, 1994, 18.

- ^ Jean Froissart, Chronicles, translator Geoffrey Brereton, Penguin Classics, Baltimore, 1968, p. 138.

- ^ Françoise Autrand, Charles V, Fayard 1994, p. 111

- ^ a b c d Anselme 1726, pp. 100–101.

- ^ a b Anselme 1726, p. 103.

- ^ a b Anselme 1726, pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b Anselme 1726, pp. 542–544

- ^ a b Anselme 1726, pp. 83–87.

- ^ Joni M. Hand, Women, Manuscripts and Identity in Northern Europe, 1350–1550, (Ashgate Publishing, 2013), 12.

- ^ a b c d e Marguerite Keane, Material Culture and Queenship in 14th-century France: The Testament of Blanche of Navarre (1331–1398), (Brill, 2016), 17.

- ^ Jean de Venette, The Chronicle of Jean de Venette, translator Jean Birdsall, editor Richard A. Newhall, (Columbia University Press, 1953), 312.

- ^ Gallo, F. Alberto (1995). Music in the Castle: Troubadours, Books, and Orators in Italian Courts of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Centuries. University of Chicago Press. p. 54.