John the Apostle

| Influences | Jesus |

|---|---|

| Influenced | Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp, Papias of Hierapolis, Odes of Solomon [11] |

John the Apostle

John the Apostle is traditionally held to be the author of the

Although the authorship of the Johannine works has traditionally been attributed to John the Apostle,[15] only a minority of contemporary scholars believe he wrote the gospel,[16] and most conclude that he wrote none of them.[15][17][18] Regardless of whether or not John the Apostle wrote any of the Johannine works, most scholars agree that all three epistles were written by the same author and that the epistles did not have the same author as the Book of Revelation, although there is widespread disagreement among scholars as to whether the author of the epistles was different from that of the gospel.[19][20][21]

References to John in the New Testament

John the Apostle was the son of Zebedee and the younger brother of James the Great. According to church tradition, their mother was Salome.[22][23] Also according to some traditions, Salome was the sister of Mary, Jesus' mother,[23][24] making Salome Jesus' aunt, and her sons John the Apostle and James were Jesus' cousins.[25]

John the Apostle is traditionally believed to be one of two disciples (the other being Andrew) recounted in John 1:35–39, who upon hearing the Baptist point out Jesus as the "Lamb of God", followed Jesus and spent the day with him, thus becoming the first two disciples called by Jesus. On this basis some traditions believe that John was first a disciple of John the Baptist, even though he is not named in this episode.[26]

According to the

John is traditionally believed to have lived on for more than fifty years after the martyrdom of his brother James, who became the first Apostle to die a martyr's death in AD 44.

Position among the apostles

John is always mentioned in the

John, along with his brother James and

Jesus sent only Peter and John into the city to make the preparation for the final Passover meal (the Last Supper).[37][38]

Many traditions identify the "disciple whom Jesus loved" in the Gospel of John as the Apostle John, but this identification is debated. At the meal itself, the "disciple whom Jesus loved" sat next to Jesus. It was customary to recline on couches at meals, and this disciple leaned on Jesus.[39] Tradition identifies this disciple as John.[40]

After the arrest of Jesus in the

After Jesus'

While he remained in Judea and the surrounding area, the other disciples returned to Jerusalem for the

The disciple whom Jesus loved

The phrase "the disciple whom Jesus loved as a brother" (ὁ μαθητὴς ὃν ἠγάπα ὁ Ἰησοῦς, ho mathētēs hon ēgapā ho Iēsous), or in John 20:2; "whom Jesus loved as a friend" (ὃν ἐφίλει ὁ Ἰησοῦς, hon ephilei ho Iēsous), is used six times in the Gospel of John,[47] but in no other New Testament accounts of Jesus. John 21:24 claims that the Gospel of John is based on the written testimony of this disciple.

The disciple whom Jesus loved is specifically referred to six times in the Gospel of John:

- It is this disciple who, while reclining beside Jesus at the Last Supper, asks Jesus, after being requested by Peter to do so, who it is that will betray him.[40]

- Later at the mother, "Woman, here is your son", and to the Beloved Disciple he says, "Here is your mother."[48]

- When Mary Magdalene discovers the empty tomb, she runs to tell the Beloved Disciple and Peter. The two men rush to the empty tomb and the Beloved Disciple is the first to reach the empty tomb. However, Peter is the first to enter.[42]

- In John 21, the last chapter of the Gospel of John, the Beloved Disciple is one of seven fishermen involved in the miraculous catch of 153 fish.[49][50]

- Also in the book's final chapter, after Jesus hints to Peter how Peter will die, Peter sees the Beloved Disciple following them and asks, "What about him?" Jesus answers, "If I want him to remain until I come, what is that to you? You follow Me!"[51]

- Again in the Gospel's last chapter, it states that the very book itself is based on the written testimony of the disciple whom Jesus loved.[52]

None of the other Gospels includes anyone in the parallel scenes that could be directly understood as the Beloved Disciple. For example, in Luke 24:12, Peter alone runs to the tomb. Mark, Matthew and Luke do not mention any one of the twelve disciples having witnessed the crucifixion.

There are also two references to an unnamed "other disciple" in John 1:35–40 and John 18:15–16, which may be to the same person based on the wording in John 20:2.[53]

New Testament author

| Part of a series of articles on |

| John in the Bible |

|---|

|

| Johannine literature |

| Authorship |

| Related literature |

| See also |

Church tradition has held that John is the author of the

In his 4th century

Until the 19th century, the authorship of the Gospel of John had been attributed to the Apostle John. However, most modern critical scholars have their doubts.[58] Some scholars place the Gospel of John somewhere between AD 65 and 85;[59][page needed] John Robinson proposes an initial edition by 50–55 and then a final edition by 65 due to narrative similarities with Paul.[60]: pp.284, 307 Other scholars are of the opinion that the Gospel of John was composed in two or three stages.[61]: p.43 Most contemporary scholars consider that the Gospel was not written until the latter third of the first century AD, and with the earliest possible date of AD 75–80: "...a date of AD 75–80 as the earliest possible date of composition for this Gospel."[62] Other scholars think that an even later date, perhaps even the last decade of the first century AD right up to the start of the 2nd century (i.e. 90 – 100), is applicable.[63]

Nonetheless, today many theological scholars continue to accept the traditional authorship. Colin G. Kruse states that since John the Evangelist has been named consistently in the writings of early Church Fathers, "it is hard to pass by this conclusion, despite widespread reluctance to accept it by many, but by no means all, modern scholars."[64]

Modern, mainstream Bible scholars generally assert that the Gospel of John has been written by an anonymous author.[65][66][67]

Regarding whether the author of the Gospel of John was an eyewitness, according to Paul N. Anderson, the gospel "contains more direct claims to eyewitness origins than any of the other Gospel traditions."[68] F. F. Bruce argues that 19:35 contains an "emphatic and explicit claim to eyewitness authority."[69] The gospel nowhere claims to have been written by direct witnesses to the reported events.[67][70][71]

Mainstream Bible scholars assert that all four gospels from the New Testament are fundamentally anonymous and most of mainstream scholars agree that these gospels have not been written by eyewitnesses.[72][73][74][75] As The New Oxford Annotated Bible (2018) has put it, "Scholars generally agree that the Gospels were written forty to sixty years after the death of Jesus."[75]

Book of Revelation

According to the

The author of the Book of Revelation identifies himself as "Ἰωάννης" ("John" in standard English translation).[77] The early 2nd-century writer Justin Martyr was the first to equate the author of Revelation with John the Apostle.[78] However, most biblical scholars now contend that these were separate individuals since the text was written around 100 AD, after the death of John the Apostle,[58][79][80] although many historians have defended the identification of the Author of the Gospel of John with that of the Book of Revelation based on the similarity of the two texts.[81]

John is considered to have been exiled to Patmos, during the persecutions under Emperor Domitian. Revelation 1:9 says that the author wrote the book on Patmos: "I, John, both your brother and companion in tribulation, ... was on the island that is called Patmos for the word of God and for the testimony of Jesus Christ." Adela Yarbro Collins, a biblical scholar at Yale Divinity School, writes:

Early tradition says that John was banished to Patmos by the Roman authorities. This tradition is credible because banishment was a common punishment used during the Imperial period for a number of offenses. Among such offenses were the practices of magic and astrology. Prophecy was viewed by the Romans as belonging to the same category, whether Pagan, Jewish, or Christian. Prophecy with political implications, like that expressed by John in the book of Revelation, would have been perceived as a threat to Roman political power and order. Three of the islands in the Sporades were places where political offenders were banished. (Pliny Natural History 4.69–70; Tacitus Annals 4.30)[83]

Some modern critical scholars have raised the possibility that John the Apostle, John the Evangelist, and John of Patmos were three separate individuals.[84] These scholars assert that John of Patmos wrote Revelation but neither the Gospel of John nor the Epistles of John. The author of Revelation identifies himself as "John" several times, but the author of the Gospel of John never identifies himself directly. Some Catholic scholars state that "vocabulary, grammar, and style make it doubtful that the book could have been put into its present form by the same person(s) responsible for the fourth gospel."[85]

Extrabiblical traditions

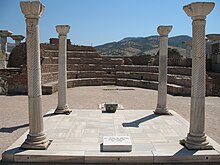

There is no information in the Bible concerning the duration of John's activity in

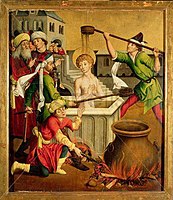

A messianic community existed at Ephesus before Paul's first labors there (cf. "the brethren"),[88] in addition to Priscilla and Aquila. The original community was under the leadership of Apollos (1 Corinthians 1:12). They were disciples of John the Baptist and were converted by Aquila and Priscilla.[89] According to tradition, after the Assumption of Mary, John went to Ephesus. Irenaeus writes of "the church of Ephesus, founded by Paul, with John continuing with them until the times of Trajan."[90] From Ephesus he wrote the three epistles attributed to him. John was banished by the Roman authorities to the Greek island of Patmos, where, according to tradition, he wrote the Book of Revelation. According to Tertullian (in The Prescription of Heretics) John was banished (presumably to Patmos) after being plunged into boiling oil in Rome and suffering nothing from it. It is said that all in the audience of Colosseum were converted to Christianity upon witnessing this miracle. This event would have occurred in the late 1st century, during the reign of the Emperor Domitian, who was known for his persecution of Christians.

When John was aged, he trained

John, the disciple of the Lord, going to bathe at Ephesus, and perceiving Cerinthus within, rushed out of the bath-house without bathing, exclaiming, "Let us fly, lest even the bath-house fall down, because Cerinthus, the enemy of the truth, is within."[91]

It is traditionally believed that John was the youngest of the apostles and survived all of them. He is said to have lived to old age, dying of natural causes at Ephesus sometime after AD 98, during the reign of Trajan, thus becoming the only apostle who did not die as a martyr.[92]

An alternative account of John's death, ascribed by later Christian writers to the early second-century bishop

John is also associated with the pseudepigraphal apocryphal text of the Acts of John, which is traditionally viewed as written by John himself or his disciple, Leucius Charinus. It was widely circulated by the second century CE but deemed heretical at the Second Council of Nicaea (787 CE). Varying fragments survived in Greek and Latin within monastic libraries. It contains strong docetic themes, but is not considered in modern scholarship to be Gnostic.[98][99]

Liturgical commemoration

The

Until 1960, another feast day which appeared in the General Roman Calendar is that of "Saint John Before the Latin Gate" on 6 May, celebrating a tradition recounted by Jerome that St John was brought to Rome during the reign of the Emperor Domitian, and was thrown in a vat of boiling oil, from which he was miraculously preserved unharmed. A church (San Giovanni a Porta Latina) dedicated to him was built near the Latin gate of Rome, the traditional site of this event.[103]

The

Other views

Islamic view

The

Latter-day Saint view

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints teaches that John the Apostle is the same person as John the Evangelist, John of Patmos, and the Beloved Disciple.[116]

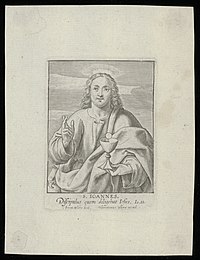

In art

As he was traditionally identified with the beloved apostle, the evangelist, and the author of the Revelation and several Epistles, John played an extremely prominent role in art from the early Christian period onward.[117] He is traditionally depicted in one of two distinct ways: either as an aged man with a white or gray beard, or alternatively as a beardless youth.[118][119] The first way of depicting him was more common in Byzantine art, where it was possibly influenced by antique depictions of Socrates;[120] the second was more common in the art of Medieval Western Europe, and can be dated back as far as 4th century Rome.[119]

Legends from the Acts of John, an apocryphal text attributed to John, contributed much to Medieval iconography; it is the source of the idea that John became an apostle at a young age.[119] One of John's familiar attributes is the chalice, often with a serpent emerging from it.[117] This symbol is interpreted as a reference to a legend from the Acts of John,[121] in which John was challenged to drink a cup of poison to demonstrate the power of his faith (the poison being symbolized by the serpent).[117] Other common attributes include a book or scroll, in reference to the writings traditionally attributed to him, and an eagle,[119] which is argued to symbolize the high-soaring, inspirational quality of these writings.[117]

In Medieval and through to Renaissance works of painting, sculpture and literature, Saint John is often presented in an androgynous or feminized manner.[122] Historians have related such portrayals to the circumstances of the believers for whom they were intended.[123] For instance, John's feminine features are argued to have helped to make him more relatable to women.[124] Likewise, Sarah McNamer argues that because of his status as an androgynous saint, John could function as an "image of a third or mixed gender"[125] and "a crucial figure with whom to identify"[126] for male believers who sought to cultivate an attitude of affective piety, a highly emotional style of devotion that, in late-medieval culture, was thought to be poorly compatible with masculinity.[127] After the Middle Ages, feminizing portrayals of Saint John continued to be made; a case in point is an etching by Jacques Bellange, shown to the right, described by art critic Richard Dorment as depicting "a softly androgynous creature with a corona of frizzy hair, small breasts like a teenage girl, and the round belly of a mature woman."[128]

In the realm of popular media, this latter phenomenon was brought to notice in Dan Brown's novel The Da Vinci Code (2003), where one of the book's characters suggests that the feminine-looking person to Jesus' right in Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper is actually Mary Magdalene rather than St. John.

Gallery of art

- John the Apostle

-

A portrait from the Book of Kells, c. 800

-

John the Apostle and St Francis by El Greco, c. 1600–1614

-

Martyrdom of Saint John the Evangelist by Master of the Winkler Epitaph

-

Valentin de Boulogne, John and Jesus

-

St. John the Evangelist in meditation by Simone Cantarini (1612–1648), Bologna

-

Saint John and the Poisoned Cup by El Greco, c. 1610–1614

-

The Last Supper, anonymous painter

See also

- Basilica of St. John

- Four Evangelists

- List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sources

- Names of John

- St. John the Evangelist on Patmos

- Vision of St. John on Patmos, 1520–1522 frescos by Antonio da Correggio

- Acts of John, a pseudepigraphal account of John's miracle work

- Saint John the Apostle, patron saint archive

References

- ^ ISBN 978-1-889814-09-4

- ISBN 978-0-06-210454-0.

- ^

Nor do we have reliable accounts from later times. What we have are legends, about some of the apostles – chiefly Peter, Paul, Thomas, Andrew, and John. But the apocryphal Acts that tell their stories are indeed highly apocryphal.

— Bart D. Ehrman, "Were the Disciples Martyred for Believing the Resurrection? A Blast From the Past", ehrmanblog.orgBart Ehrman

— Emerson Green, "Who Would Die for a Lie?", The big problem with this argument [of who would die for a lie] is that it assumes precisely what we don't know. We don't know how most of the disciples died. The next time someone tells you they were all martyred, ask them how they know. Or better yet, ask them which ancient source they are referring to that says so. The reality is [that] we simply do not have reliable information about what happened to Jesus' disciples after he died. In fact, we scarcely have any information about them while they were still living, nor do we have reliable accounts from later times. What we have are legends. - ISBN 9780810872837.

Though not in complete agreement, most scholars believe that John died of natural causes in Ephesus

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Prophets In Islam And Judaism, Brandon M. Wheeler, Disciples of Christ: "Islam identifies the disciples of Jesus as Peter, Philip, Andrew, Matthew, Thomas, John, James, Bartholomew, and Simon"

- ISBN 9780810868366.

- ISBN 9780816528400.

Saint John the Evangelist is patron of miners (in Carinthia), Turkey (Asia Minor), sculptors, art dealers, bookbinders ...

- ISBN 9781684510474.

John is a patron saint of Asia Minor and Turkey and Turks because of his missionary work there.

- ^ ISBN 9780190208684.

- ^ Brian Bartholomew Tan. "On Envy". Church of Saint Michael. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- JSTOR 27900527.

- ^ Henry Chadwick (2021). "Saint John the Apostle". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Imperial Aramaic: ܝܘܚܢܢ ܫܠܝܚܐ, Yohanān Shliḥā; Hebrew: יוחנן בן זבדי, Yohanan ben Zavdi; Coptic: ⲓⲱⲁⲛⲛⲏⲥ or ⲓⲱ̅ⲁ; Հովհաննես[citation needed]

- ^ Ivanoff, Jonathan. "Life of St. John the Theologian". www.stjt.org. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-87484-696-6.

Although ancient traditions attributed to the Apostle John the Fourth Gospel, the Book of Revelation, and the three Epistles of John, modern scholars believe that he wrote none of them.

- ^ Lindars, Edwards & Court 2000, p. 41.

- ISBN 978-0-8146-5999-1.

- ISBN 978-0-87484-472-6. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ISBN 9781433530814.

- ISBN 9780814612835.

- ISBN 9781467422321.

- ^ by comparing Matthew 27:56 to Mark 15:40

- ^ a b "Topical Bible: Salome". biblehub.com. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "John 19 Commentary – William Barclay's Daily Study Bible". StudyLight.org. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "The Disciples of Our Saviour". biblehub.com. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "John, The Apostle – International Standard Bible Encyclopedia". Bible Study Tools. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ Media, Franciscan (27 December 2015). "Saint John the Apostle". Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ Lk 9:51–56

- ^ Luke 9:49–50 NKJV

- ^ Acts 1:13

- ^ Mark 3:13–19

- ^ Matthew 10:2–4

- ^ Lk 6:14–16

- ^ Mark 5:37

- ^ Matthew 17:1

- ^ Matthew 26:37

- ^ Lk 22:8

- ^ While Luke states that this is the Passover (Lk 22:7–9) the Gospel of John specifically states that the Passover meal occurs on the following day (Jn 18:28)

- ^ a b "St John The Evangelist". www.ewtn.com.

- ^ a b Jn 13:23–25

- ^ Jn 19:25–27

- ^ a b Jn 20:1–10

- ^ Acts 3:1 et seq.

- ^ Acts 4:3

- ^ Acts 8:14

- ^ "Fonck, Leopold. "St. John the Evangelist." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 6 Feb. 2013". Newadvent.org. 1 October 1910. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ John 13:23, 19:26, 20:2, 21:7, 21:20, 21:24

- ^ Jn 19:26–27

- ^ Jn 21:1–25

- ISBN 0-8028-3711-5.

- ^ John 21:20–23

- ^ John 21:24

- ^ Brown, Raymond E. 1970. "The Gospel According to John (xiii–xxi)". New York: Doubleday & Co. Pages 922, 955

- ^ Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical History Book vi. Chapter xxv.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Apocalypse".

- ^ The History of the Church by Eusibius. Book three, point 24.

- ^ Thomas Patrick Halton, On illustrious men, Volume 100 of The Fathers of the Church, CUA Press, 1999. P. 19.

- ^ a b Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible (Palo Alto: Mayfield, 1985) p. 355

- ISBN 978-0-07-296548-3

- ISBN 978-0-334-02300-5.

- ISBN 0-664-25703-8/ 978-0664257033

- ^ Gail R. O'Day, introduction to the Gospel of John in New Revised Standard Translation of the Bible, Abingdon Press, Nashville, 2003, p.1906

- ^ Reading John, Francis J. Moloney, SDB, Dove Press, 1995

- ISBN 0-8028-2771-3, p. 28.

- ^ E P Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus, (Penguin, 1995) page 63 – 64.

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2000:43) The New Testament: a historical introduction to early Christian writings. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Bart D. Ehrman (2005:235) Lost Christianities: the battles for scripture and the faiths we never knew Oxford University Press, New York.

- ^ Paul N. Anderson, The Riddles of the Fourth Gospel, p. 48.

- ^ F. F. Bruce, The Gospel of John, p. 3.

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2004:110) Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code: A Historian Reveals What We Really Know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman(2006:143) The lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot: a new look at betrayer and betrayed. Oxford University Press.

- ISBN 978-0199254255.

The historical narratives, the Gospels and Acts, are anonymous, the attributions to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John being first reported in the mid-second century by Irenaeus

- ^ Reddish 2011, pp. 13, 42.

- ^ Perkins & Coogan 2010, p. 1380.

- ^ a b Coogan et al. 2018, p. 1380.

- ^ Rev. 1:9

- ^ "Revelation, Book of." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, 81.4

- ISBN 0-19-515462-2.

- ^ a b "Church History, Book III, Chapter 39". The Fathers of the Church. NewAdvent.org. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ISBN 9781118050866.

other contemporary scholars have vigorously defended the traditional view of apostolic authorship.

- ^ saint, Jerome. "De Viris Illustribus (On Illustrious Men) Chapter 9 & 18". newadvent.org. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Adela Collins. "Patmos". Harper's Bible Dictionary. Paul J. Achtemeier, gen. ed. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1985. p755.

- Deseret Book, 1992) p. 379. Griggs favors the "one John" theory but mentions that some modern scholars have hypothesized that there are multiple Johns.

- ^ Introduction. Saint Joseph Edition of the New American Bible: Translated from the Original Languages with Critical Use of All the Ancient Sources: including the Revised New Testament and the Revised Psalms. New York: Catholic Book Pub., 1992. 386. Print.

- ^ "Heilige Johannes". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ cf. Ac 12:1–17

- ^ Acts 18:27

- The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New advent. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Grant, Robert M. (1997). Irenaeus of Lyons. London: Routledge. p. 2.

- Against Heresies, III.3.4.

- ^ a b "John the Apostle". CCEL.

- ^ Cheyne, Thomas Kelly (1901). "John, Son of Zebedee". Encyclopaedia Biblica. Vol. 2. Adam & Charles Black. pp. 2509–11. Although Papias' works are no longer extant, the fifth-century ecclesiastical historian Philip of Side and the ninth-century monk George Hamartolos both stated that Papias had written that John was "slain by the Jews."

- ISBN 978-9-00417633-1. Rasimus finds corroborating evidence for this tradition in "two martyrologies from Edessa and Carthage" and writes that "Mark 10:35–40//Matt. 20:20–23 can be taken to portray Jesus predicting the martyrdom of both the sons of Zebedee."

- ISBN 9780567087423.

- ^ Swete, Henry Barclay (1911). The Apocalypse of St. John (3 ed.). Macmillan. pp. 179–180.

- Procopius of Caesarea, On Buildings General Index, trans. H. B. Dewing and Glanville Downey, vol. 7, Loeb Classical Library343 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1940), 319

- ^ "The Acts of John". gnosis.org. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- )

- ^ "The Calendar". 16 October 2013. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ General Roman Calendar of Pope Pius XII

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Saint Andrew Daily Missal with Vespers for Sundays and Feasts by Dom. Gaspar LeFebvre, O.S.B., Saint Paul, Minnesota: The E.M. Lohmann Co., 1952, pp.1325–1326

- ^ "Repose of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian". www.oca.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian". www.oca.org. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "Synaxis of the Holy, Glorious and All-Praised Twelve Apostles". www.oca.org. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "February 15, 2020. + Orthodox Calendar". orthochristian.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Qur'an 3:52

- ^ Prophet's Sirah by Ibn Hisham, Chapter: Sending messengers of Allah's Messenger to kings, p.870

- ISBN 978-0810843059.

Muslim exegesis identifies the disciples of Jesus as Peter, Andrew, Matthew, Thomas, Philip, John, James, Bartholomew, and Simon

- ^ Musnad el Imam Ahmad Volume 4, Publisher: Dar al Fikr, p.72, Hadith#17225

- ^ "John, Son of Zebedee". wwwchurchofjesuschrist.org.

- ^ Doctrine and Covenants 27:12

- ^ Priesthood restoration. CES Letter.

- ^ A CES Letter Reply: Faithful Answers For Those Who Doubt

- ^ LDS Church, 1979

- ^ a b c d James Hall, "John the Evangelist", Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, rev. ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1979)

- ^ Sources:

- James Hall, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), 129, 174–75.

- Carolyn S. Jerousek, "Christ and St. John the Evangelist as a Model of Medieval Mysticism", Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 6 (2001), 16.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ Jadranka Prolović, "Socrates and St. John the Apostle: the interchangеable similarity of their portraits" Zograf, vol. 35 (2011), 9: "It is difficult to locate when and where this iconography of John originated and what the prototype was, yet it is clearly visible that this iconography of John contains all of the main characteristics of well-known antique images of Socrates. This fact leads to the conclusion that Byzantine artists used depictions of Socrates as a model for the portrait of John."

- ^ J.K. Elliot (ed.), A Collection of Apocryphal Christian Literature in an English Translation Based on M.R. James (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993/2005), 343–345.

- ^ *James Hall, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), 129, 174–75.

- Jeffrey F. Hamburger, St. John the Divine: The Deified Evangelist in Medieval Art and Theology. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), xxi–xxii; ibidem, 159–160.

- Carolyn S. Jerousek, "Christ and St. John the Evangelist as a Model of Medieval Mysticism", Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 6 (2001), 16.

- Annette Volfing, John the Evangelist and Medieval Writing: Imitating the Inimitable. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 139.

- ^ *Jeffrey F. Hamburger, St. John the Divine: The Deified Evangelist in Medieval Art and Theology. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), xxi–xxii.

- Carolyn S. Jerousek, "Christ and St. John the Evangelist as a Model of Medieval Mysticism" Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 6 (2001), 20.

- Sarah McNamer, Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 142–148.

- Annette Volfing, John the Evangelist and Medieval Writing: Imitating the Inimitable. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 139.

- ^ *Carolyn S. Jerousek, "Christ and St. John the Evangelist as a Model of Medieval Mysticism" Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 6 (2001), 20.

- Annette Volfing, John the Evangelist and Medieval Writing: Imitating the Inimitable. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 139.

- ^ Sarah McNamer, Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 142.

- ^ Sarah McNamer, Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 145.

- ^ Sarah McNamer, Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 142–148.

- ^ Richard Dorment (15 February 1997). "The Sacred and the Sensual". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 26 February 2016.

Sources

- Coogan, Michael; Brettler, Marc; Newsom, Carol; Perkins, Pheme (1 March 2018). The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press. p. 1380. ISBN 978-0-19-027605-8.

- Lindars, Barnabas; Edwards, Ruth; Court, John M. (2000). The Johannine Literature. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84127-081-4.

- ISBN 978-0-521-48593-7.

- Perkins, Pheme; Coogan, Michael D. (2010). Brettler, Marc Z.; Newsom, Carol (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press. p. 1380.

- Reddish, Mitchell (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-1426750083.

External links

- Eastern Orthodox icon and Synaxarion of Saint John the Apostle and Evangelist (May 8)

- John the Apostle in Art

- John in Art

- Repose of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian Orthodox synaxarionfor 26 September

- Works by John the Apostle at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John the Apostle at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Saint John at Internet Archive