Jokhang

| Jokhang | |

|---|---|

Barkhor, Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region | |

| Country | China |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Vihara, Tibetan, Nepalese |

| Founder | Songtsen Gampo |

| Date established | 7th century |

Historic Ensemble of the Potala Palace, Lhasa | |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (iv), (vi) |

| Reference | 707ter-002 |

| Inscription | 1994 (18th Session) |

| Extensions | 2000, 2001 |

| Area | 7.5 ha (810,000 sq ft) |

| Buffer zone | 130 ha (14,000,000 sq ft) |

| Coordinates | 29°39′11″N 91°2′51″E / 29.65306°N 91.04750°E |

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

The Jokhang (

Around the 14th century, the temple was associated with the

Location

The temple, considered the "spiritual heart of the city" and the most sacred in Tibet,

Etymology

Rasa Thrulnag Tsuklakang ("House of Mysteries" or "House of Religious Science") was the Jokhang's ancient name.[9] When King Songtsen built the temple his capital city was known as Rasa ("Goats")[citation needed], since goats were used to move earth during its construction. After the king's death, Rasa[citation needed] became known as Lhasa (Place of the Gods); the temple was called Jokhang—"Temple of the Lord"—derived from Jowo Shakyamuni Buddha, its primary image.[10] The Jokhang's Chinese name is Dazhao;[11] it is also known as Zuglagkang, Qoikang Monastery[12] Tsuglakhang[13] and Tsuglhakhange.[8]

History

Tibetans viewed their country as a living entity controlled by srin ma (pronounced "sinma"), a wild demoness who opposed the propagation of Buddhism in the country. To thwart her evil intentions, King Songtsen Gampo (the first king of a unified Tibet)[14] developed a plan to build twelve temples across the country. The temples were built in three stages. In the first stage central Tibet was covered with four temples, known as the "four horns" (ru bzhi). Four more temples, (mtha'dul), were built in the outer areas in the second stage; the last four, the yang'dul, were built on the country's frontiers. The Jokhang temple was finally built in the heart of the srin ma, ensuring her subjugation.[15]

To forge ties with neighboring Nepal, Songtsen Gampo sent envoys to King Amsuvarman seeking his daughter's hand in marriage and the king accepted. His daughter, Bhrikuti, came to Tibet as the king's Nepalese wife (tritsun; belsa in Tibetan). The image of

Gampo, wishing to obtain a second wife from China, sent his ambassador to

The oldest part of the temple was built in 652 by Songtsen Gampo. To find a location for the temple, the king reportedly tossed his hat (a ring in another version)

The temple's design and construction are attributed to Nepalese craftsmen. After Songtsen Gampo's death, Queen Wencheng reportedly moved the statue of Jowo from the Ramoche temple to the Jokhang temple to secure it from Chinese attack. The part of the temple known as the Chapel was the hiding place of the Jowo Sakyamuni.[19]

During the reign of King Tresang Detsan from 755 to 797, Buddhists were persecuted because the king's minister, Marshang Zongbagyi (a devotee of

Beginning in about the 14th century, the temple was associated with the Vajrasana in India. It is said that the image of Buddha deified in the Jokhang is the 12-year-old Buddha earlier located in the Bodh Gaya Temple in India, indicating "historical and ritual" links between India and Tibet. Tibetans call Jokhang the "Vajrasana of Tibet" (Bod yul gyi rDo rje gdani), the "second Vajrasana" (rDo rje gdan pal) and "Vajrasan, the navel of the land of snow" (Gangs can sa yi lte ba rDo rje gdani).[23]

After the occupation of Nepal by the

In Chinese development of Lhasa, Barkhor Square was encroached when the walkway around the temple was destroyed. An inner walkway was converted into a

During the

Two

According to the Dalai Lama, among the many images in the temple was an image of Chenrizi, made of clay in the temple, within which the small wooden statue of the Buddha brought from Nepal was hidden. The image was in the temple for 1300 years, and when Songtsen Gampo died his soul was believed to have entered the small wooden statue. During the Cultural Revolution, the clay image was smashed and the smaller Buddha was given by a Tibetan to the Dalai Lama.[19]

In 2000, the Jokhang became a

On February 17, 2018, the temple caught fire at 6:40 p.m. (local time), before sunset in Lhasa, with the blaze lasting until late that evening. Although photos and videos about the fire were spread on Chinese social media, which showed the eaved roof of a section of the building lit with roaring yellow flames and emitting a haze of smoke, these images were quickly censored and disappeared. The official newspaper Tibet Daily briefly claimed online that the fire was "quickly extinguished" with "no deaths or injuries" at the late night, while The

Architecture

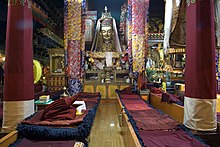

The Jokhang temple covers an area of 2.51 hectares (6.2 acres). When it was built during the seventh century, it had eight rooms on two floors to house scriptures and sculptures of the Buddha. The temple had brick-lined floors, columns and door frames and carvings made of wood. During the Tubo period, there was conflict between followers of Buddhism and the indigenous Bon religion. Changes in dynastic rule affected the Jokhang Monastery; after 1409, during the Ming dynasty, many improvements were made to the temple. The second and third floors of the Buddha Hall and the annex buildings were built during the 11th century. The main hall is the four-story Buddha Hall.[37]

The temple has an east-west orientation, facing Nepal to the west in honour of Princess Bhrikuti.

The central Buddha Hall is tall, with a large, paved courtyard.

In addition to the main hall and its adjoining halls, on both sides of the Buddha Hall are dozens of 20-square-metre (220 sq ft) chapels. The Prince of Dharma chapel is on the third floor, including sculptures of Songtsen Gampo, Princess Wencheng, Princess Bhrikuti, Gar Tongtsan (the Tabo minister) and Thonmi Sambhota, the inventor of Tibetan script. The halls are surrounded by enclosed walkways.[43]

Decorations of winged apsaras, human and animal figurines, flowers and grasses are carved on the superstructure. Images of sphinxes with a variety of expressions are carved below the roof.[43]

The temple complex has more than 3,000 images of the Buddha and other deities (including an 85-foot (26 m) image of the Buddha)[11] and historical figures, in addition to manuscripts and other objects. The temple walls are decorated with religious and historical murals.[38]

On the rooftop and roof ridges are iconic statues of golden deer flanking a

In addition to walking around the temple and spinning prayer wheels, pilgrims prostrate themselves before approaching the main deity;[39] some crawl a considerable distance to the main shrine.[17] The prayer chanted during this worship is "Om mani padme hum" (Hail to the jewel in the lotus). Pilgrims queue on both sides of the platform to place a ceremonial scarf (katak) around the Buddha's neck or touch the image's knee.[39] A walled enclosure in front of the Jokhang, near the Tang Dynasty-Tubo Peace Alliance Tablet, contains the stump of a willow known as the "Tang Dynstay Willow" or the "Princess Willow". The willow was reportedly planted by Princess Wencheng.[28]

Buddhist scriptures and sculptures

The Jokhang has a sizable, significant collection of cultural artifacts, including Tang-dynasty bronze sculptures and finely-sculpted figures in different shapes from the Ming dynasty. The book 108 Buddhist Statues in Tibet by Ulrich von Schroeder, published in 2008, contains a DVD with digital photographs of the 419 most important Buddhist sculptures in the collection of the Jokhang [1]. Among hundreds of

See also

References

- ^ Gyurme Dorje, Review of Jokhang: Tibet's Most Sacred Buddhist Temple, JIATS, #6, December 2011

- ^ a b c "Jokhang". MAPS, Places. University of Virginia.

- ^ a b Mayhew, Kelly & Bellezza 2008, p. 96.

- ^ a b Dorje 2010, p. 160.

- ^ Klimczuk & Warner2009, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d An 2003, p. 69.

- ^ McCue 2011, p. 67.

- ^ a b Mayhew, Kelly & Bellezza 2008, p. 102.

- ^ Dalton 2004, p. 55.

- ^ Barron 2003, p. 487.

- ^ a b Perkins 2013, p. 986.

- ^ Service 1983, p. 120.

- ^ "Contrary to Reports, Fire not at Jokhang Chapel: Central Tibetan Administration". Central Tibetan Administration. 18 February 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-02-18. Retrieved 2018-02-18.

Dharamsala; In light of the news reports of a massive fire that was believed to have emerged from Jokhang chapel (chapel that houses the Jowo-Buddha Shakyamui statue) in the temple premises, in the heart of Lhasa city, reliable sources have told the Central Tibetan Administration leadership that the source of the fire is not the Jowo chapel but from an adjacent chapel within the Jokhang temple premises known in Tibetan as Tsuglakhang. Images and videos circulating last evening on social media show the Jokhang temple premises, one of the holiest Buddhist temples in Tibet engulfed in flames. A bystander is heard wailing and chanting a prayer in the name of Tenzin Gyatso (the 14th Dalai Lama). It is reported that the fire that broke out at 6:40 pm (Lhasa time) was extinguished and there was no casualties and damage to property is yet to be ascertained. CTA President Dr Lobsang Sangay who is currently on a six-day official visit to Japan sighed relief that the fire did not affect Jokhang chapel but cautioned Tibetans in Tibet to remain alert at large public gatherings especially during occasions such as Losar. "At this point in time I cannot comment much until the cause of the fire is brought to light, but it is disturbing to see tragic accidents take place at Jokhang temple premises, one of the most hallowed sites in Tibet and a UNESCO World Heritage site," lamented Ven Karma Gelek Yuthok, Minister for Religion and Culture.

- ^ a b "Jokhang Temple, Lhasa". sacred-destinations.com. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Powers 2007, p. 233.

- ^ a b Powers 2007, p. 146.

- ^ a b Brockman 2011, p. 263.

- ^ a b c d Davidson & Gitlitz 2002, p. 339.

- ^ a b c Buckley 2012, p. 142.

- ISBN 978-7-5085-0232-8.

- ^ a b Barnett 2010, p. 161.

- ^ Jabb 2015, p. 55.

- ^ Huber 2008, p. 119.

- ^ Huber 2008, p. 233.

- ^ "Tibet and the Cultural Revolution". Séagh Kehoe. 30 January 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Woeser (8 August 2017). "My Conversation with Dawa, a Lhasa Red Guard Who Took Part in the Smashing of the Jokhang Temple". High Peaks Pure Earth. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Laird 2007, p. 39.

- ^ a b c An 2003, p. 72.

- ^ a b Representatives 1994, p. 1402.

- ^ a b Buckley 2012, p. 143.

- ^ "China destroys the ancient Buddhist symbols of Lhasa City in Tibet". Tibet Post. 9 May 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ Buckley, Chris (17 February 2018). "Fire Strikes Hallowed Site in Tibet, the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa". The New York Times. New York Times. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "Fire-hit Jokhang temple streets reopen after blaze at Tibet holy site". AFP. 19 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ Finney, Richard (2018-02-20). "Tibet's Jokhang Temple Closes For Three Days, Raising Concerns Over Damage". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ "China says fire in sacred Tibetan monastery not arson". The Associated Press. 22 February 2018. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ "Contrary to Reports, Fire not at Jokhang Chapel". Central Tibetan Administration. February 19, 2018. Archived from the original on March 24, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ a b An 2003, p. 69-70.

- ^ a b "Historic Ensemble of the Potala Palace, Lhasa". UNESCO Organization. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Davidson & Gitlitz 2002, p. 340.

- ^ An 2003, p. 69-71.

- ^ Brockman 2011, p. 263-64.

- ^ An 2003, p. 70.

- ^ a b An 2003, p. 71.

- ^ Mayhew, Kelly & Bellezza 2008, p. 103.

Bibliography

- An, Caidan (2003). Tibet China: Travel Guide. 五洲传播出版社. ISBN 978-7-5085-0374-5.

- Barnett, Robert (2010). Lhasa: Streets with Memories. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13681-5.

- Barron, Richard (10 February 2003). The Autobiography of Jamgon Kongtrul: A Gem of Many Colors. Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 978-1-55939-970-8.

- Brockman, Norbert C. (13 September 2011). Encyclopedia of Sacred Places. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-655-3.

- Buckley, Michael (2012). Tibet. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-382-5.

- Dalton, Robert H. (2004). Sacred Places of the World: A Religious Journey Across the Globe. Abhishek. ISBN 978-81-8247-051-4.

- Davidson, Linda Kay; Gitlitz, David Martin (2002). Pilgrimage: From the Ganges to Graceland : an Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-004-8.

- Dorje, Gyurme (2010). Jokhang: Tibet's Most Sacred Buddhist Temple. Edition Hansjorg Mayer. ISBN 978-5-00-097692-0.

- Huber, Toni (15 September 2008). The Holy Land Reborn: Pilgrimage and the Tibetan Reinvention of Buddhist India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-35650-1.

- Jabb, Lama (10 June 2015). Oral and Literary Continuities in Modern Tibetan Literature: The Inescapable Nation. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-0334-1.

- Klimczuk, Stephen; Warner, Gerald (2009). Secret Places, Hidden Sanctuaries: Uncovering Mysterious Sites, Symbols, and Societies. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4027-6207-9.

- Laird, Thomas (10 October 2007). The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-4327-3.

- Mayhew, Bradley; Kelly, Robert; Bellezza, John Vincent (2008). Tibet. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-569-7.

- McCue, Gary (1 March 2011). Trekking Tibet. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-1-59485-411-8.

- Perkins, Dorothy (19 November 2013). Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-93569-6.

- Powers, John (25 December 2007). Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism. Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 978-1-55939-835-0.

- Representatives, Australia. Parliament. House of (1994). Parliamentary Debates Australia: House of Representatives. Commonwealth Government Printer.

- Service, United States. Foreign Broadcast Information (1983). Daily Report: People's Republic of China. National Technical Information Service.

- von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2001. Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet. Vol. One: India & Nepal; Vol. Two: Tibet & China. (Volume One: 655 pages with 766 illustrations; Volume Two: 675 pages with 987 illustrations). Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, Ltd. ISBN 962-7049-07-7

- von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2008. 108 Buddhist Statues in Tibet. (212 p., 112 colour illustrations) (DVD with 527 digital photographs mostly of Jokhang Bronzes). Chicago: Serindia Publications. ISBN 962-7049-08-5

Further reading

- Vitali, Roberto. 1990. Early Temples of Central Tibet. Serindia Publications. London. ISBN 0-906026-25-3. Chapter Three: "Lhasa Jokhang and its Secret Chapel." Pages 69–88.