Julius Caesar (play)

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (September 2020) |

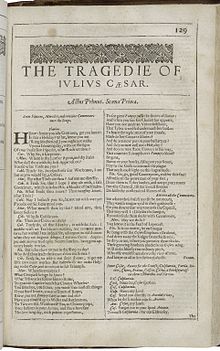

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar (First Folio title: The Tragedie of Ivlivs Cæsar), often abbreviated as Julius Caesar, is a history play and tragedy by William Shakespeare first performed in 1599.

In the play,

Characters

Triumvirs after Caesar's death

- Octavius Caesar

- Mark Antony

- Lepidus

Conspirators against Caesar

Tribunes

Roman Senate Senators

- Cicero

- Publius

- Popilius Lena

Citizens

- Calpurnia – Caesar's wife

- Portia – Brutus' wife

- Soothsayer – a person supposed to be able to foresee the future

- Cinna – poet

- Cobbler

- Carpenter

- Poet (believed to be based on Marcus Favonios)[1]

- Lucius – Brutus' attendant

Loyal to Brutus and Cassius

- Volumnius

- Titinius

- Young Cato – Portia's brother

- Messala – messenger

- Varrus

- Clitus

- Claudio

- Dardanius

- Strato

- Lucilius

- Flavius(non-speaking role)

- Labeo (non-speaking role)

- Pindarus – Cassius' bondman

Other

- servant

- Antony's servant

- servant

- Messenger

- Other attendants

Synopsis

The play opens with two

The conspirators attempt to demonstrate that they killed Caesar for the good of Rome, to prevent an autocrat. They prove this by not attempting to flee the scene. Brutus delivers an oration defending his actions, and for the moment, the crowd is on his side. However, Antony makes a subtle and eloquent speech over Caesar's corpse, beginning "Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears!"[3] He deftly turns public opinion against the assassins by manipulating the emotions of the common people, in contrast to the rational tone of Brutus's speech, yet there is a method in his rhetorical speech and gestures. Antony reminds the crowd of the good Caesar had done for Rome, his sympathy with the poor, and his refusal of the crown at the Lupercal, thus questioning Brutus's claim of Caesar's ambition; he shows Caesar's bloody, lifeless body to the crowd to have them shed tears and gain sympathy for their fallen hero; and he reads Caesar's will, in which every Roman citizen would receive 75 drachmas. Antony, even as he states his intentions against it, rouses the mob to drive the conspirators from Rome. Amid the violence, an innocent poet, Cinna, is confused with the conspirator Lucius Cinna and is taken by the mob, which kills him for such "offenses" as his bad verses.

Brutus then attacks Cassius for supposedly soiling the noble act of

At the Battle of Philippi, Cassius and Brutus, knowing that they will probably both die, smile their last smiles to each other and hold hands. During the battle, Cassius has his servant kill him after hearing of the capture of his best friend, Titinius. After Titinius, who was not captured, sees Cassius's corpse, he commits suicide. However, Brutus wins that stage of the battle, but his victory is not conclusive. With a heavy heart, Brutus battles again the next day. He asks his friends to kill him, but the friends refuse. He loses and commits suicide by running on his sword, held for him by a loyal soldier.

The play ends with a tribute to Brutus by Antony, who proclaims that Brutus has remained "the noblest Roman of them all"[6] because he was the only conspirator who acted, in his mind, for the good of Rome. There is then a small hint at the friction between Antony and Octavius which characterizes another of Shakespeare's Roman plays, Antony and Cleopatra.

Sources

The main source of the play is Thomas North's translation of Plutarch's Lives.[7][8]

Deviations from Plutarch

- Shakespeare makes Caesar's triumph take place on the day of Lupercalia (15 February) instead of six months earlier.

- For dramatic effect, he makes the Capitol the venue of Caesar's death rather than the Curia Pompeia (Curia of Pompey).

- Caesar's murder, the funeral, Antony's oration, the reading of the will, and the arrival of Octavius all take place on the same day in the play. However, historically, the assassination took place on 15 March (The Ides of March), the will was published on 18 March, the funeral was on 20 March, and Octavius arrived only in May.

- Shakespeare makes the Triumvirs meet in Rome instead of near Bononia to avoid an additional locale.

- He combines the two Battles of Philippi although there was a 20-day interval between them.

- Shakespeare has Caesar say Et tu, Brute? ("And you, Brutus?") before he dies. Plutarch and Suetonius each report that he said nothing, with Plutarch adding that he pulled his toga over his head when he saw Brutus among the conspirators,[9] though Suetonius does record other reports that Caesar said in Latin, "Ista quidem vis est" (This is violence).[10][11] The Latin words Et tu, Brute?, however, were not devised by Shakespeare for this play since they are attributed to Caesar in earlier Elizabethan works and had become conventional by 1599.

Shakespeare deviated from these historical facts to curtail time and compress the facts so that the play could be staged more easily. The tragic force is condensed into a few scenes for heightened effect.

Date and text

Julius Caesar was originally published in the First Folio of 1623, but a performance was mentioned by Thomas Platter the Younger in his diary in September 1599. The play is not mentioned in the list of Shakespeare's plays published by Francis Meres in 1598. Based on these two points, as well as several contemporary allusions, and the belief that the play is similar to Hamlet in vocabulary, and to Henry V and As You Like It in metre,[12] scholars have suggested 1599 as a probable date.[13]

The text of Julius Caesar in the First Folio is the only authoritative text for the play. The Folio text is notable for its quality and consistency; scholars judge it to have been set into type from a theatrical prompt-book.[14]

The play contains many

Analysis and criticism

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2021) |

Historical background

Maria Wyke has written that the play reflects the general anxiety of Elizabethan England over a succession of leadership. At the time of its creation and first performance,

Protagonist debate

Critics of Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar differ greatly in their views of Caesar and Brutus. Many have debated whether Caesar or Brutus is the protagonist of the play because the title character dies in Act Three, Scene One. But Caesar compares himself to the

Myron Taylor, in his essay "Shakespeare's Julius Caesar and the Irony of History", compares the logic and philosophies of Caesar and Brutus. Caesar is deemed an intuitive philosopher who is always right when he goes with his instinct; for instance, when he says he fears Cassius as a threat to him before he is killed, his intuition is correct. Brutus is portrayed as a man similar to Caesar, but whose passions lead him to the wrong reasoning, which he realizes in the end when he says in V.v.50–51, "Caesar, now be still:/ I killed not thee with half so good a will".[17]

Joseph W. Houppert acknowledges that some critics have tried to cast Caesar as the protagonist, but that ultimately Brutus is the driving force in the play and is therefore the tragic hero. Brutus attempts to put the republic over his relationship with Caesar and kills him. Brutus makes the political mistakes that bring down the republic that his ancestors created. He acts on his passions, does not gather enough evidence to make reasonable decisions, and is manipulated by Cassius and the other conspirators.[18]

Traditional readings of the play may maintain that Cassius and the other conspirators are motivated largely by

Performance history

The play was probably one of Shakespeare's first to be performed at the Globe Theatre.[21] Thomas Platter the Younger, a Swiss traveler, saw a tragedy about Julius Caesar at a Bankside theatre on 21 September 1599, and this was most likely Shakespeare's play, as there is no obvious alternative candidate. (While the story of Julius Caesar was dramatized repeatedly in the Elizabethan/Jacobean period, none of the other plays known is as good a match with Platter's description as Shakespeare's play.)[22]

After the theatres re-opened at the start of the

Notable performances

- 1864: Winter Garden Theater in New York City. Junius Jr. played Cassius, Edwin played Brutus and John Wilkes played Mark Antony. This landmark production raised funds to erect a statue of Shakespearein Central Park, which remains to this day.

- 29 May 1916: A one-night performance in the natural bowl of Beachwood Canyon, Hollywood drew an audience of 40,000 and starred Tyrone Power Sr. and Douglas Fairbanks Sr. The student bodies of Hollywood and Fairfax High Schools played opposing armies, and the elaborate battle scenes were performed on a huge stage as well as the surrounding hillsides. The play commemorated the tercentenary of Shakespeare's death. A photograph of the elaborate stage and viewing stands can be seen on the Library of Congress website. The performance was lauded by L. Frank Baum.[24]

- 1926: Another elaborate performance of the play was staged as a benefit for the Actors Fund of America at the Hollywood Bowl. Caesar arrived for the Lupercal in a chariot drawn by four white horses. The stage was the size of a city block and dominated by a central tower 80 feet (24 m) in height. The event was mainly aimed at creating work for unemployed actors. Three hundred gladiatorsappeared in an arena scene not featured in Shakespeare's play; a similar number of girls danced as Caesar's captives; a total of three thousand soldiers took part in the battle sequences.

- 1937: National Theater in January 1938,[28]: 341 running a total of 157 performances.[29] A second company made a five-month national tour with Caesar in 1938, again to critical acclaim.[30]: 357

- 1950: film version.

- 1977: Gielgud made his final appearance in a Shakespearean role on stage as Caesar in John Schlesinger's production at the Royal National Theatre. The cast also included Ian Charleson as Octavius.

- 1994: Arvind Gaur directed the play in India with Jaimini Kumar as Brutus and Deepak Ochani as Caesar (24 shows); later on he revived it with Manu Rishi as Caesar and Vishnu Prasad as Brutus for the Shakespeare Drama Festival, Assam in 1998. Arvind Kumar translated Julius Caesar into Hindi. This production was also performed at the Prithvi international theatre festival, at the India Habitat Centre, New Delhi.

- 2005: Denzel Washington played Brutus in the first Broadway production of the play in over fifty years. The production received universally negative reviews but was a sell-out because of Washington's popularity at the box office.[31]

- 2012: The Royal Shakespeare Company staged an all-black production under the direction of Gregory Doran.

- 2012: An all-female production starring Harriet Walter as Brutus and Frances Barber as Caesar was staged at the Donmar Warehouse, directed by Phyllida Lloyd. In October 2013, the production transferred to New York's St. Ann's Warehouse in Brooklyn.

- 2018: The Bridge Theatre staged Julius Caesar as one of its first productions, under the direction of Nicholas Hytner, with Ben Whishaw, Michelle Fairley, and David Morrissey as leads. This mirrors the play's status as one of the first productions at the Globe Theatre in 1599.

Adaptations and cultural references

One of the earliest cultural references to the play came in Shakespeare's own Hamlet. Prince Hamlet asks Polonius about his career as a thespian at university, and Polonius replies: "I did enact Julius Caesar. I was killed in the Capitol. Brutus killed me." This is a likely meta-reference, as Richard Burbage is generally accepted to have played leading men Brutus and Hamlet, and the older John Heminges to have played Caesar and Polonius.

In 1851, the German composer

The Canadian comedy duo

In 1984, the

In 2006, Chris Taylor from the Australian comedy team The Chaser wrote a comedy musical called Dead Caesar which was shown at the Sydney Theatre Company in Sydney.

The line "The Evil That Men Do", from the speech made by Mark Antony following Caesar's death ("The evil that men do lives after them; The good is oft interred with their bones.") has had many references in media, including the titles of:

- A song by Iron Maiden.

- A politically oriented film directed by J. Lee Thompson in 1984.

- A novel in the Buffy the Vampire Slayer series.

The 2008 movie Me and Orson Welles, based on a book of the same name by Robert Kaplow, is a fictional story centered around Orson Welles' famous 1937 production of Julius Caesar at the Mercury Theatre. British actor Christian McKay is cast as Welles, and co-stars with Zac Efron and Claire Danes.

The 2012 Italian drama film Caesar Must Die (Italian: Cesare deve morire), directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, follows convicts in their rehearsals ahead of a prison performance of Julius Caesar.

In the Ray Bradbury book Fahrenheit 451, some of the character Beatty's last words are "There is no terror, Cassius, in your threats, for I am armed so strong in honesty that they pass me as an idle wind, which I respect not!"

The play's line "the fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves", spoken by Cassius in Act I, scene 2, is often referenced in popular culture. The line gave its name to the

The line "And therefore think him as a serpent's egg / Which hatched, would, as his kind grow mischievous; And kill him in the shell" spoken by Brutus in Act II, Scene 1, is referenced in the

The title of Agatha Christie's novel Taken at the Flood, titled There Is a Tide in its American edition, refers to an iconic line of Brutus: "There is a tide in the affairs of men, which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune." (Act IV, Scene III).

The line “There is a tide in the affairs of men, which taken at the flood, leads on to fortune. Omitted, all the voyage of their life is bound in shallows and in miseries. On such a full sea are we now afloat. And we must take the current when it serves, or lose our ventures” is recited by

Film and television adaptations

Julius Caesar has been adapted to a number of film productions, including:

- Julius Caesar (Vitagraph Company of America, 1908), produced by J. Stuart Blackton and directed by William V. Ranous, who also played Antony.[35]

- Julius Caesar (Avon Productions, 1950), directed by David Bradley, who played Brutus; Charlton Heston played Antony and Harold Tasker played Caesar.[36]

- MGM, 1953), directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz and produced by John Houseman; starring James Mason as Brutus, Marlon Brando as Antony and Louis Calhern as Caesar.[36]

- An Honourable Murder (1960), directed by Godfrey Grayson;[37] depicted the play in a modern business setting.[38]

- Antony & Cleopatra.

- Julius Caesar (Commonwealth United, 1969), directed by Stuart Burge, produced by Peter Snell, starring Jason Robards as Brutus, Charlton Heston as Antony and John Gielgud as Caesar.[36]

- British Universities Film & Video Council database states that the work "transforms the play into a modern political conspiracy thriller with modern dialogue and many strong allusions to political events in the early 1970."[40]

- Time-Life TV, 1978), a television adaptation in the BBC Television Shakespeare series, directed by Herbert Wise and produced by Cedric Messina, starring Richard Pasco as Brutus, Keith Michell as Antony and Charles Gray as Caesar.[36]

- Julius Caesar (2010), is a short film starring Randy Harrison as Brutus and John Shea as Julius Caesar. Directed by Patrick J Donnelly and produced by Dan O'Hare.[41]

- playing themselves.[42]

- Julius Caesar (2012), a BBC television film adaptation of the Royal Shakespeare Company stage production of the same year directed by Gregory Doran with an all-Black cast, sets the tragedy in post-independence Africa with echoes of the Arab Spring. The film stars Paterson Joseph as Brutus, Ray Fearon as Antony, Jeffery Kissoon as Caesar, Cyril Nri as Cassius and Adjoa Andoh as Portia.[43]

- Zulfiqar (2016), a Bengali-language Indian film by Srijit Mukherji that is an adaptation of both Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra and a tribute to the film The Godfather.[44]

Contemporary political references

Modern adaptions of the play have often made contemporary political references,[45] with Caesar depicted as resembling a variety of political leaders, including Huey Long, Margaret Thatcher, and Tony Blair,[46] as well as Fidel Castro and Oliver North.[47][48] Scholar A. J. Hartley stated that this is a fairly "common trope" of Julius Caesar performances: "Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, the rule has been to create a recognizable political world within the production. And often people in the title role itself look like or feel like somebody either in recent or current politics."[46] A 2012 production of Julius Caesar by the Guthrie Theater and The Acting Company "presented Caesar in the guise of a black actor who was meant to suggest President Obama."[45] This production was not particularly controversial.[45]

In 2017, however, a modern adaptation of the play at

See also

- 1599 in literature

- Assassinations in fiction

- Caesar's Comet

- Mark Antony's Funeral Speech

- "The dogs of war"

References

Citations

- ISBN 978-0-521-53513-7.

- ^ "Julius Caesar, Act 3, Scene 1, Line 77".

- ^ " Julius Caesar, Act 3, Scene 2, Line 73".

- ^ " Julius Caesar, Act 4, Scene 3, Lines 19–21".

- ^ "Julius Caesar, Act 4, Scene 3, Line 283".

- ^ " Julius Caesar, Act 5, Scene 5, Line 68".

- ISBN 0-19-283606-4.

- ^ Pages from Plutarch, Shakespeare's Source for Julius Caesar.

- ^ Plutarch, Caesar 66.9

- ^ Suetonius, Julius 82.2).

- ^ Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, translated by Robert Graves, Penguin Classic, p. 39, 1957.

- ^ Wells and Dobson (2001, 229).

- ^ Spevack (1988, 6), Dorsch (1955, vii–viii), Boyce (2000, 328), Wells, Dobson (2001, 229)

- ^ Wells and Dobson, ibid.

- ISBN 978-1-4051-2599-4.

- ^ Reynolds 329–333

- ^ Taylor 301–308

- ^ Houppert 3–9

- New Haven and London: Yale University Press, p. 118.

- ^ Wills, Op. cit., p. 117.

- ^ Evans, G. Blakemore (1974). The Riverside Shakespeare. Houghton Mifflin Co. p. 1100.

- Thomas Dekker, Michael Drayton, Thomas Middleton, Anthony Munday, and John Webster, in 1601–02, too late for Platter's reference. Neither play has survived. The anonymous Caesar's Revenge dates to 1606, while George Chapman's Caesar and Pompey date from ca. 1613. E. K. Chambers, Elizabethan Stage, Vol. 2, p. 179; Vol. 3, pp. 259, 309; Vol. 4, p. 4.

- ^ Halliday, p. 261.

- ^ Baum, L. Frank (15 June 1916). "Julius Caesar: An Appreciation of the Hollywood Production". Mercury Magazine. Retrieved 15 March 2024 – via Hungry Tiger Press.

- ^ "Theatre: New Plays in Manhattan: Nov. 22, 1937". TIME. 22 November 1937. Archived from the original on 16 December 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ISBN 0-671-21034-3.

- ^ Lattanzio, Ryan (2014). "Orson Welles' World, and We're Just Living in It: A Conversation with Norman Lloyd". EatDrinkFilms.com. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ ISBN 0-06-016616-9.

- ^ "News of the Stage; 'Julius Caesar' Closes Tonight". The New York Times. 28 May 1938. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-670-86722-6.

- ^ "A Big-Name Brutus in a Caldron of Chaosa". The New York Times. 4 April 2005. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ^ Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5th edition, ed. Eric Blom, Vol. VII, p. 733

- ^ "Rinse the Blood Off My Toga". Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project at the University of Guelph. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Herbert Mitgang of The New York Times, 14 March 1984, wrote: "The famous Mercury Theater production of Julius Caesar in modern dress staged by Orson Welles in 1937 was designed to make audiences think of Mussolini's Blackshirts – and it did. The Riverside Shakespeare Company's lively production makes you think of timeless ambition and antilibertarians anywhere."

- ^ Maria Wyke, Caesar in the USA (University of California Press, 2012), p. 60.

- ^ a b c d Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television (eds. Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells: Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp. 29–31.

- ^ Darryll Grantley, Historical Dictionary of British Theatre: Early Period (Scarecrow Press, 2013), p. 228.

- ^ Stephen Chibnall & Brian McFarlane, The British 'B' Film (Palgrave Macmillan/British Film Institute, 2009), p. 252.

- ^ Michael Brooke. "Julius Caesar on Screen". Screenonline. British Film Institute.

- British Universities Film & Video Council.

- ^ "Julius Caesar (2010) - IMDb". IMDb.

- ^ French, Philip (3 March 2013). "Caesar Must Die – review". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ "Julius Caesar (Royal Shakespeare Company)". Films Media Group. Infobase. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ Anindita Acharya, My film Zulfiqar is a tribute to The Godfather, says Srijit Mukherji, Hindustan Times (20 September 2016).

- ^ a b c d Peter Marks, When 'Julius Caesar' was given a Trumpian makeover, people lost it. But is it any good, Washington Post (16 June 2017).

- ^ a b c d Frank Pallotta, Trump-like 'Julius Caesar' isn't the first time the play has killed a contemporary politician, CNN (12 June 2017).

- ISBN 978-0-472-05577-7.

- ^ "Tragedies - Julius Caesar". Latinx Shakespeares. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ "Delta and Bank of America boycott 'Julius Caesar' play starring Trump-like character". The Guardian. 12 June 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ Alexander, Harriet (12 June 2017). "Central Park play depicting Julius Caesar as Donald Trump causes theatre sponsors to withdraw". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Delta, BofA Drop Support For 'Julius Caesar' That Looks Too Much Like Trump". NPR. 12 June 2017.

- ^ Beckett, Lois (12 June 2017). "Trump as Julius Caesar: anger over play misses Shakespeare's point, says scholar". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- The Raw Story. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ "'Trump death' in Julius Caesar prompts threats to wrong theatres". CNN. 19 June 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ Wahlquist, Calla (17 June 2017). "'This is violence against Donald Trump': rightwingers interrupt Julius Caesar play". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ Link, Taylor (22 June 2017). "Cops investigate death threats made against "Caesar" director's wife". Salon. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ Mantyla, Kyle (20 June 2017). "Sandy Rios Sees No Difference Between Shakespeare And Feeding Christians to the Lions". Right Wing Watch. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

Secondary sources

- Boyce, Charles. 1990. Encyclopaedia of Shakespeare, New York, Roundtable Press.

- ISBN 0-19-811511-3.

- ISBN 0-14-053011-8.

- Houppert, Joseph W. "Fatal Logic in 'Julius Caesar'". South Atlantic Bulletin. Vol. 39, No.4. Nov. 1974. 3–9.

- Kahn, Coppelia. "Passions of some difference": Friendship and Emulation in Julius Caesar. Julius Caesar: New Critical Essays. Horst Zander, ed. New York: Routledge, 2005. 271–283.

- Parker, Barbara L. "The Whore of Babylon and Shakespeares's Julius Caesar." Studies in English Literature (Rice); Spring95, Vol. 35 Issue 2, p. 251, 19p.

- Reynolds, Robert C. "Ironic Epithet in Julius Caesar". Shakespeare Quarterly. Vol. 24. No.3. 1973. 329–333.

- Taylor, Myron. "Shakespeare's Julius Caesar and the Irony of History". Shakespeare Quarterly. Vol. 24, No. 3. 1973. 301–308.

- Wells, Stanley and Michael Dobson, eds. 2001. The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare Oxford University Press

External links

- Complete Annotated Text on One Page

- Text of Julius Caesar, fully edited by John Cox, as well as original-spelling text, facsimiles of the 1623 Folio text, and other resources, at the Internet Shakespeare Editions

- Julius Caesar Navigator Includes Shakespeare's text with notes, line numbers, and a search function.

- No Fear Shakespeare Archived 23 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine Includes the play line by line with interpretation.

- Julius Caesar Archived 21 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine at the British Library

- Julius Caesar at Standard Ebooks

- Julius Caesar at Project Gutenberg

- Julius Caesar – by The Tech

- Julius Caesar – Searchable and scene-indexed version.

- Julius Caesar in modern English

- Julius Caesar translated into Latin by Dr. Hilgers[permanent dead link]

- Lesson plans for Julius Caesar at Web English Teacher

Julius Caesar public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Julius Caesar public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Quicksilver Radio Theater adaptation of Julius Caesar, which may be heard online, at PRX.org (Public Radio Exchange).

- Julius Caesar Read Online in Flash version.

- Clear Shakespeare Julius Caesar – A word-by-word audio guide through the play.