Kansas

Kansas | |

|---|---|

|

Plains cottonwood |

Kansas (

For thousands of years, what is now Kansas was home to numerous and diverse Indigenous tribes. The first settlement of non-indigenous people in Kansas occurred in 1827 at Fort Leavenworth. The pace of settlement accelerated in the 1850s, in the midst of political wars over the slavery debate. When it was officially opened to settlement by the U.S. government in 1854 with the Kansas–Nebraska Act, conflict between abolitionist Free-Staters from New England and pro-slavery settlers from neighboring Missouri broke out over the question of whether Kansas would become a free state or a slave state, in a period known as Bleeding Kansas. On January 29, 1861,[15][16] Kansas entered the Union as a free state, hence the unofficial nickname "The Free State". Passage of the Homestead Acts in 1862 brought a further influx of settlers, and the booming cattle trade of the 1870s attracted some of the Wild West's most iconic figures to western Kansas.[17][18]

As of 2015, Kansas was among the most productive agricultural states, producing high yields of wheat, corn, sorghum, and soybeans.[19] In addition to its traditional strength in agriculture, Kansas possesses an extensive aerospace industry. Kansas, which has an area of 82,278 square miles (213,100 square kilometers) is the 15th-largest state by area, the 36th most-populous of the 50 states, with a population of 2,940,865[20] according to the 2020 census, and the 10th least densely populated. Residents of Kansas are called Kansans. Mount Sunflower is Kansas's highest point at 4,039 feet (1,231 meters).[21]

Etymology

The name Kansas derives from the

History

Before

Between 1763 and 1803 the territory of Kansas was integrated into

In 1803, most of modern Kansas was

In 1827, Fort Leavenworth became the first permanent settlement of white Americans in the future state.[26] The Kansas–Nebraska Act became law on May 30, 1854, establishing Nebraska Territory and Kansas Territory, and opening the area to broader settlement by whites. Kansas Territory stretched all the way to the Continental Divide and included the sites of present-day Denver, Colorado Springs, and Pueblo.

Bleeding Kansas and the Civil War

The first non-military settlement of Euro-Americans in Kansas Territory consisted of abolitionists from Massachusetts and other Free-Staters who founded the town of Lawrence and attempted to stop the spread of slavery from neighboring Missouri.

Missouri and Arkansas continually sent settlers into Kansas Territory along its eastern border to sway votes in favor of slavery prior to Kansas statehood elections. Directly presaging the American Civil War these forces collided, entering into skirmishes and guerrilla conflicts that earned the territory the nickname Bleeding Kansas. These included John Brown's Pottawatomie massacre of 1856.

Kansas was

Settlement and the Wild West

Passage of the

At the same time, the

20th century

In response to demands of

Kansas suffered severe and environmental damage in the 1930s due to the combined effects of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, and large numbers of people left southwestern Kansas in particular for better opportunities elsewhere.[31] The outbreak of World War II spurred rapid growth in aircraft manufacturing near Wichita in the so-called Battle of Kansas, and the aerospace sector remains a significant portion of the Kansan economy to this day.

Geography

Kansas is bordered by

Geology

Kansas is underlain by a sequence of horizontal to gently westward

Topography

The western two-thirds of the state, lying in the great central plain of the United States, has a generally flat or undulating surface, while the eastern third has many hills and forests. The land gradually rises from east to west; its altitude ranges from 684 ft (208 m) along the Verdigris River at Coffeyville in Montgomery County, to 4,039 ft (1,231 m) at Mount Sunflower, 0.5 miles (0.80 kilometers) from the Colorado border, in Wallace County. It is a common misconception that Kansas is the flattest state in the nation—in 2003, a tongue-in-cheek study famously declared the state "flatter than a pancake".[33] In fact, Kansas has a maximum topographic relief of 3,360 ft (1,020 m),[34] making it the 23rd flattest U.S. state measured by maximum relief.[35]

Rivers

Around 74 mi (119 km) of the state's northeastern boundary is defined by the Missouri River. The Kansas River (locally known as the Kaw), formed by the junction of the Smoky Hill and Republican rivers at appropriately-named Junction City, joins the Missouri River at Kansas City, after a course of 170 mi (270 km) across the northeastern part of the state.

The

Kansas's other rivers are the Saline and Solomon Rivers, tributaries of the Smoky Hill River; the Big Blue, Delaware, and Wakarusa, which flow into the Kansas River; and the Marais des Cygnes, a tributary of the Missouri River. Spring River is located between Riverton and Baxter Springs.

National parks and historic sites

Areas under the protection of the National Park Service include:[36]

- Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Sitein Topeka

- Fort Larned National Historic Site in Larned

- Fort Scott National Historic Site in Bourbon County

- Nicodemus National Historic Site at Nicodemus

- Pony Express National Historic Trail

- Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve near Strong City

Flora and fauna

In Kansas, there are currently 238 species of rare animals and 400 rare plants.

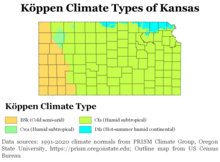

Climate

In the

The western third of the state—from roughly the U.S. Route 83 corridor westward—has a semi-arid steppe climate. Summers are hot, often very hot, and generally less humid. Winters are highly changeable between warm and very cold. The western region receives an average of about 16 inches (410 millimeters) of precipitation per year. Chinook winds in the winter can warm western Kansas all the way into the 80 degrees Fahrenheit (27 degrees Celsius) range.

The south-central and southeastern portions of the state, including the Wichita area, have a humid subtropical climate with hot and humid summers, milder winters, and more precipitation than elsewhere in Kansas. Some features of all three climates can be found in most of the state, with droughts and changeable weather between dry and humid not uncommon, and both warm and cold spells in the winter.

Temperatures in areas between U.S. Routes 83 and 81, as well as the southwestern portion of the state along and south of U.S. 50, reach 90 °F (32 °C) or above on most days of June, July, and August. High humidity added to the high temperatures sends the heat index into life-threatening territory, especially in Wichita, Hutchinson, Salina, Russell, Hays, and Great Bend. Temperatures are often higher in Dodge City, Garden City, and Liberal, but the heat index in those three cities is usually lower than the actual air temperature.

Although temperatures of 100 °F (38 °C) or higher are not as common in areas east of U.S. 81, higher humidity and the urban heat island effect lead most summer days to heat indices between 107 °F (42 °C) and 114 °F (46 °C) in Topeka, Lawrence, and the Kansas City metropolitan area. Also, combined with humidity between 85 and 95 percent, dangerous heat indices can be experienced at every hour of the day.

Precipitation ranges from about 47 inches (1,200 mm) annually in the state's southeast corner to about 16 inches (410 mm) in the southwest. Snowfall ranges from around 5 inches (130 mm) in the fringes of the south, to 35 inches (890 mm) in the far northwest. Frost-free days range from more than 200 days in the south, to 130 days in the northwest. Thus, Kansas is the country's ninth or tenth sunniest state, depending on the source. Western Kansas is as sunny as parts of California and Arizona.

Kansas is prone to severe weather, especially in the spring and the early-summer. Despite the frequent sunshine throughout much of the state, due to its location at a climatic boundary prone to intrusions of multiple air masses, the state is vulnerable to strong and severe thunderstorms. Some of these storms become supercell thunderstorms; these can produce some tornadoes, occasionally those of EF3 strength or higher. Kansas averages more than 50 tornadoes annually.[43] Severe thunderstorms sometimes drop some very large hail over Kansas as well. Furthermore, these storms can even bring in flash flooding and damaging straight line winds.

According to NOAA, the all-time highest temperature recorded in Kansas is (121 °F or 49.4 °C) on July 24, 1936, near Alton in Osborne County, and the all-time low is −40 °F (−40 °C) on February 13, 1905, near Lebanon in Smith County. Alton and Lebanon are approximately 50 miles (80 km) apart.

Kansas's record high of 121 °F (49.4 °C) ties with North Dakota for the fifth-highest record high in an American state, behind California (134 °F or 56.7 °C), Arizona (128 °F or 53.3 °C), Nevada (125 °F or 51.7 °C), and New Mexico (122 °F or 50 °C).

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concordia | 36/17 | 43/22 | 54/31 | 64/41 | 74/52 | 85/62 | 91/67 | 88/66 | 80/56 | 68/44 | 51/30 | 40/21 |

| Dodge City | 41/19 | 48/24 | 57/31 | 67/41 | 76/52 | 87/62 | 93/67 | 91/66 | 82/56 | 70/44 | 55/30 | 44/22 |

| Goodland | 39/16 | 45/20 | 53/26 | 63/35 | 72/46 | 84/56 | 89/61 | 87/60 | 78/50 | 66/38 | 50/25 | 41/18 |

| Topeka | 37/17 | 44/23 | 55/33 | 66/43 | 75/53 | 84/63 | 89/68 | 88/65 | 80/56 | 69/44 | 53/32 | 41/22 |

| Wichita | 40/20 | 47/25 | 57/34 | 67/44 | 76/54 | 87/64 | 93/69 | 92/68 | 82/59 | 70/47 | 55/34 | 43/24 |

Settlement

|

Known as rural flight, the last few decades have been marked by a migratory pattern out of the countryside into cities. Out of all the cities in these Midwestern states, 89% have fewer than 3,000 people, and hundreds of those have fewer than 1,000. In Kansas alone, there are more than 6,000 ghost towns and dwindling communities,[45] according to one Kansas historian, Daniel C. Fitzgerald. At the same time, some of the communities in Johnson County (metropolitan Kansas City) are among the fastest-growing in the country.

| City | Population* | Growth rate** | Metro area | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wichita | 397,532 | 3.97% | Wichita |

| 2 | Overland Park | 197,238 | 13.77% | Kansas City, MO-KS |

| 3 | Kansas City | 156,607 | 7.42% | Kansas City |

| 4 | Olathe | 141,290 | 12.25% | Kansas City |

| 5 | Topeka | 126,587 | −0.70% | Topeka |

| 6 | Lawrence | 94,934 | 8.32% | Lawrence |

| 7 | Shawnee | 67,311 | 8.20% | Kansas City |

| 8 | Lenexa | 57,434 | 19.18% | Kansas City |

| 9 | Manhattan | 54,100 | 3.48% | Manhattan |

| 10 | Salina | 46,889 | -1.71% | ‡ |

| 11 | Hutchinson | 40,006 | −4.93% | ‡ |

| 12 | Leavenworth | 37,351 | 5.96% | Kansas City |

| 13 | Leawood | 33,902 | 6.39% | Kansas City |

| 14 | Garden City | 28,151 | 5.60% | ‡ |

| 15 | Dodge City | 27,788 | 1.64% | ‡ |

| 16 | Derby | 25,625 | 15.65% | Wichita |

| 17 | Emporia | 24,139 | -3.12% | ‡ |

| 18 | Gardner | 23,287 | 21.77% | Kansas City |

| 19 | Prairie Village | 22,957 | 7.04% | Kansas City |

| 20 | Junction City | 22,932 | -1.80% | Manhattan |

| 21 | Hays | 21,116 | 2.95% | ‡ |

| 22 | Pittsburg | 20,646 | 2.04% | ‡ |

| 23 | Liberal | 19,825 | −3.41% | ‡ |

| 24 | Newton | 18,602 | −2.77% | Wichita |

| *2020 census micropolitan area

| ||||

Kansas has 627 incorporated cities. By state statute, cities are divided into three classes as determined by the population obtained "by any census of enumeration". A city of the third class has a population of less than 5,000, but cities reaching a population of more than 2,000 may be certified as a city of the second class. The second class is limited to cities with a population of less than 25,000, and upon reaching a population of more than 15,000, they may be certified as a city of the first class. First and second class cities are independent of any township and are not included within the township's territory.

Birth data

Note: Births in table don't add up, because Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

Race

|

2013[47] | 2014[48] | 2015[49] | 2016[50] | 2017[51] | 2018[52] | 2019[53] | 2020[54] | 2021[55] | 2022[56] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White: | 34,178 (88.0%) | 34,420 (87.7%) | 34,251 (87.5%) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| > Non-Hispanic White | 28,281 (72.8%) | 28,504 (72.7%) | 28,236 (72.1%) | 26,935 (70.8%) | 25,594 (70.1%) | 25,323 (69.8%) | 24,549 (69.4%) | 23,663 (68.8%) | 24,056 (69.3%) | 23,669 (68.8%) |

| Black | 2,967 (7.6%) | 3,097 (7.9%) | 3,090 (7.9%) | 2,543 (6.7%) | 2,657 (7.3%) | 2,575 (7.1%) | 2,458 (6.9%) | 2,412 (7.0%) | 2,316 (6.7%) | 2,208 (6.4%) |

| Asian | 1,401 (3.6%) | 1,359 (3.5%) | 1,483 (3.8%) | 1,299 (3.4%) | 1,255 (3.4%) | 1,228 (3.4%) | 1,216 (3.4%) | 1,146 (3.3%) | 1,031 (3.0%) | 1,055 (3.1%) |

| American Indian | 293 (0.7%) | 347 (0.9%) | 330 (0.8%) | 173 (0.5%) | 248 (0.7%) | 217 (0.6%) | 214 (0.6%) | 162 (0.5%) | 183 (0.5%) | 241 (0.7%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 6,143 (15.8%) | 6,132 (15.6%) | 6,300 (16.1%) | 6,298 (16.5%) | 5,963 (16.3%) | 5,977 (16.5%) | 6,071 (17.2%) | 5,970 (17.4%) | 6,122 (17.6%) | 6,309 (18.3%) |

| Total Kansas | 38,839 (100%) | 39,223 (100%) | 39,154 (100%) | 38,053 (100%) | 36,519 (100%) | 36,261 (100%) | 35,395 (100%) | 34,376 (100%) | 34,705 (100%) | 34,401 (100%) |

- Since 2016, data for births of White Hispanic origin are not collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

Life expectancy

The residents of Kansas have a life expectancy near the U.S. national average. In 2013, males in Kansas lived an average of 76.6 years compared to a male national average of 76.7 years and females lived an average of 81.0 years compared to a female national average of 81.5 years. Increases in life expectancy between 1980 and 2013 were below the national average for males and near the national average for females. Male life expectancy in Kansas between 1980 and 2014 increased by an average of 5.2 years, compared to a male national average of a 6.7-year increase. Life expectancy for females in Kansas between 1980 and 2014 increased by 4.3 years, compared to a female national average of a 4.0 year increase.[57]

Using 2017–2019 data, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation calculated that life expectancy for Kansas counties ranged from 75.8 years for Wyandotte County to 81.7 years for Johnson County. Life expectancy for the state as a whole was 78.5 years.[58] Life expectancy for the United States as a whole in 2019 was 78.8 years.[59]

Regions

Northeast Kansas

The northeastern portion of the state, extending from the eastern border to Junction City and from the Nebraska border to south of Johnson County is home to more than 1.5 million people in the Kansas City (Kansas portion), Manhattan, Lawrence, and Topeka metropolitan areas. Overland Park, a young city incorporated in 1960, has the largest population and the largest land area in the county. It is home to Johnson County Community College.

Olathe is the county seat and home to Johnson County Executive Airport. The cities of Olathe, Shawnee, De Soto and Gardner have some of the state's fastest growing populations. The cities of Overland Park, Lenexa, Olathe, De Soto, and Gardner are also notable because they lie along the former route of the Santa Fe Trail. Among cities with at least one thousand residents, Mission Hills has the highest median income in the state.

Several institutions of higher education are located in Northeast Kansas including Baker University (the oldest university in the state, founded in 1858 and affiliated with the United Methodist Church) in Baldwin City, Benedictine College (sponsored by St. Benedict's Abbey and Mount St. Scholastica Monastery and formed from the merger of St. Benedict's College (1858) and Mount St. Scholastica College (1923)) in Atchison, MidAmerica Nazarene University in Olathe, Ottawa University in Ottawa and Overland Park, Kansas City Kansas Community College and KU Medical Center in Kansas City, and KU Edwards Campus in Overland Park. Less than an hour's drive to the west, Lawrence is home to the University of Kansas, the largest public university in the state, and Haskell Indian Nations University.

To the north,

To the west, nearly a quarter million people reside in the Topeka metropolitan area.

South Central Kansas

In south-central Kansas, the Wichita metropolitan area is home to more than 600,000 people.[61] Wichita is the largest city in the state in terms of both land area and population. 'The Air Capital' is a major manufacturing center for the aircraft industry and the home of Wichita State University. Before Wichita was 'The Air Capital' it was a Cowtown.[62] With a number of nationally registered historic places, museums, and other entertainment destinations, it has a desire to become a cultural mecca in the Midwest. Wichita's population growth has grown by double digits and the surrounding suburbs are among the fastest growing cities in the state. The population of Goddard has grown by more than 11% per year since 2000.[63] Other fast-growing cities include Andover, Maize, Park City, Derby, and Haysville.

Wichita was one of the first cities to add the city commissioner and city manager in their form of government.[62] Wichita is also home of the nationally recognized Sedgwick County Zoo.[62]

Up river (the

Southeast Kansas

Southeast Kansas has a unique history with a number of nationally registered historic places in this coal-mining region. Located in Crawford County (dubbed the Fried Chicken Capital of Kansas), Pittsburg is the largest city in the region and the home of Pittsburg State University. The neighboring city of Frontenac in 1888 was the site of the worst mine disaster in the state in which an underground explosion killed 47 miners. "Big Brutus" is located 1.5 miles (2.4 km) outside the city of West Mineral. Along with the restored fort, historic Fort Scott has a national cemetery designated by President Lincoln in 1862. The region also shares a Media market with Joplin, Missouri, a city in Southwest Missouri.

Central and North-Central Kansas

Northwest Kansas

Westward along the Interstate, the city of Russell, traditionally the beginning of sparsely-populated northwest Kansas, was the base of former U.S. Senator Bob Dole and the boyhood home of U.S. Senator Arlen Specter. The city of Hays is home to Fort Hays State University and the Sternberg Museum of Natural History, and is the largest city in the northwest with a population of around 20,001.

Two other landmarks are located in smaller towns in Ellis County: the "Cathedral of the Plains" is located 10 miles (16 km) east of Hays in Victoria, and the boyhood home of Walter Chrysler is 15 miles (24 km) west of Hays in Ellis. West of Hays, population drops dramatically, even in areas along I-70, and only two towns containing populations of more than 4,000: Colby and Goodland, which are located 35 miles (56 km) apart along I-70.

Southwest Kansas

Dodge City, famously known for the cattle drive days of the late 19th century, was built along the old Santa Fe Trail route. The city of Liberal is located along the southern Santa Fe Trail route. The first wind farm in the state was built east of Montezuma. Garden City has the Lee Richardson Zoo. In 1992, a short-lived secessionist movement advocated the secession of several counties in southwest Kansas.[65]

Around the state

Located midway between Kansas City, Topeka, and Wichita in the heart of the Bluestem Region of the Flint Hills, the city of Emporia has several nationally registered historic places and is the home of Emporia State University, well known for its Teachers College. It was also the home of newspaper man William Allen White.

Demographics

Population

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of Kansas was 2,913,314 on July 1, 2019, a 2.11% increase since the 2010 United States census and an increase of 58,387, or 2.05%, since 2010.[66] This includes a natural increase since the last census of 93,899 (246,484 births minus 152,585 deaths) and a decrease due to net migration of 20,742 people out of the state. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 44,847 people, and migration within the country produced a net loss of 65,589 people.[67] At the 2020 census, its population was 2,937,880.

In 2018, The top countries of origin for Kansas's immigrants were Mexico, India, Vietnam, Guatemala and China.[68]

The population density of Kansas is 52.9 people per square mile.[69] The center of population of Kansas is located in Chase County, at 38°27′N 96°32′W / 38.450°N 96.533°W, approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) north of the community of Strong City.[70]

The focus on labor-efficient grain-based agriculture—such as a large wheat farm that requires only one or a few people with large

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 2,397 homeless people in Kansas.[72][73]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 107,206 | — | |

| 1870 | 364,399 | 239.9% | |

| 1880 | 996,096 | 173.4% | |

| 1890 | 1,428,108 | 43.4% | |

| 1900 | 1,470,495 | 3.0% | |

| 1910 | 1,690,949 | 15.0% | |

| 1920 | 1,769,257 | 4.6% | |

| 1930 | 1,880,999 | 6.3% | |

| 1940 | 1,801,028 | −4.3% | |

| 1950 | 1,905,299 | 5.8% | |

| 1960 | 2,178,611 | 14.3% | |

| 1970 | 2,246,578 | 3.1% | |

| 1980 | 2,363,679 | 5.2% | |

| 1990 | 2,477,574 | 4.8% | |

| 2000 | 2,688,418 | 8.5% | |

| 2010 | 2,853,118 | 6.1% | |

| 2020 | 2,937,880 | 3.0% | |

| 1910–2020[74] | |||

Race and ethnicity

According to the 2021 United States census estimates, the racial makeup of the population was: (3.2%), and American Indian and Alaska Native (1.2%). At the 2020 census, its racial and ethnic makeup was 75.6% White, 5.7% African American, 2.9% Asian American, 1.1% Native American, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 4.9% some other race, and 9.5% two or more races.

| Racial composition | 1990[76] | 2000[77] | 2010[78] | 2020[79] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

White |

90.1% | 86.1% | 83.8% | 75.6% |

Black |

5.8% | 5.8% | 5.9% | 5.7% |

Asian |

1.3% | 1.7% | 2.4% | 2.9% |

| Native | 0.9% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 1.1% |

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

– | – | 0.1% | 0.1% |

Other race |

2.0% | 3.4% | 3.9% | 4.9% |

Two or more races |

– | 2.1% | 3.0% | 9.5% |

Non-Hispanic White 30–40%50–60%60–70%70–80%80–90%90%+Hispanic or Latino 50–60%60–70%

As of 2004, the population included 149,800 foreign-born (5.5% of the state population). The ten largest reported ancestry groups, which account for nearly 90% of the population, in the state are:

Mexicans are present in the southwest and make up nearly half the population in certain counties. Many African Americans in Kansas are descended from the Exodusters, newly freed blacks who fled the South for land in Kansas following the Civil War.[82]

There is a growing Asian community in Kansas. Since 1965, more and more Asian families have moved to Kansas from countries such as the Philippines, China, Korea, India, and Vietnam.[83]

- Birth data

Race

|

2013[84] | 2014[85] | 2015[86] | 2016[87] | 2017[88] | 2018[89] | 2019[90] | 2020[91] | 2021[92] | 2022[93] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White: | 34,178 (88.0%) | 34,420 (87.7%) | 34,251 (87.5%) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| > non-Hispanic White | 28,281 (72.8%) | 28,504 (72.7%) | 28,236 (72.1%) | 26,935 (70.8%) | 25,594 (70.1%) | 25,323 (69.8%) | 24,549 (69.4%) | 23,663 (68.8%) | 24,056 (69.3%) | 23,669 (68.8%) |

| Black | 2,967 (7.6%) | 3,097 (7.9%) | 3,090 (7.9%) | 2,543 (6.7%) | 2,657 (7.3%) | 2,575 (7.1%) | 2,458 (6.9%) | 2,412 (7.0%) | 2,316 (6.7%) | 2,208 (6.4%) |

| Asian | 1,401 (3.6%) | 1,359 (3.5%) | 1,483 (3.8%) | 1,299 (3.4%) | 1,255 (3.4%) | 1,228 (3.4%) | 1,216 (3.4%) | 1,146 (3.3%) | 1,031 (3.0%) | 1,055 (3.1%) |

| American Indian | 293 (0.7%) | 347 (0.9%) | 330 (0.8%) | 173 (0.5%) | 248 (0.7%) | 217 (0.6%) | 214 (0.6%) | 162 (0.5%) | 183 (0.5%) | 163 (0.5%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 6,143 (15.8%) | 6,132 (15.6%) | 6,300 (16.1%) | 6,298 (16.5%) | 5,963 (16.3%) | 5,977 (16.5%) | 6,071 (17.2%) | 5,970 (17.4%) | 6,122 (17.6%) | 6,309 (18.3%) |

| Total Kansas | 38,839 (100%) | 39,223 (100%) | 39,154 (100%) | 38,053 (100%) | 36,519 (100%) | 36,261 (100%) | 35,395 (100%) | 34,376 (100%) | 34,705 (100%) | 34,401 (100%) |

As of 2011, 35.0% of Kansas's population younger than one year of age belonged to minority groups (i.e., did not have two parents of non-Hispanic white ancestry).[94]

Language

English is the most-spoken language in Kansas, with 91.3% of the population speaking only English at home as of the year 2000. 5.5% speak Spanish, 0.7% speak German, and 0.4% speak Vietnamese.[95]

Religion

The 2014 Pew Religious Landscape Survey showed the religious makeup of adults in Kansas was as follows:[96] 57% Protestant, 18% Catholic, 1% Mormon, 1% Jehovah's Witness, 20% unaffiliated, 1% Buddhism, and 2% other religions. In 2010, the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) reported that the Catholic Church had the highest number of adherents in Kansas (at 426,611), followed by the United Methodist Church with 202,989 members, and the Southern Baptist Convention, reporting 99,329 adherents.[97]

In 2020, ARDA reported 414,939 Catholics, 165,658 United Methodists, and 164,486 Southern Baptists.[98] In 2022, the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI)'s study revealed 74% of the total population were Christian; among them, 59% were Protestant, 13% Catholic, and 2% Mormon. The religiously unaffiliated were 23% of the population, Unitarian Universalists 1%, and New Agers 1%.[99]

Kansas's capital Topeka is sometimes cited as the home of

Kansas is the location of the second Baha'i community west of Egypt, when the Baha'i community of

Topeka is also home of the Westboro Baptist Church, a hate group according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.[101][102][103] The church has garnered worldwide media attention for picketing the funerals of U.S. servicemen and women for what church members claim as "necessary to combat the fight for equality for gays and lesbians". They have sometimes successfully raised lawsuits against the city of Topeka.

Economy

Total Employment of the metropolitan areas in the State of Kansas by total Non-farm Employment in 2016[104]

- Kansas Portion of the Kansas City MO-KS MSA: 468,400 non-farm, accounting for 40.9% of state GDP in 2015[105]

- Wichita, KS MSA: 297,300 non-farm

- Topeka, KS MSA: 112,600 non-farm

- Lawrence KS, MSA: 54,000 non-farm

- Manhattan, KS MSA: 44,200 non-farm

- Total employment: 1,184,710

Total Number of employer establishments in 2016: 74,884[106]

The Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates that Kansas's total gross domestic product in 2014 was US$140.964 billion.[107] In 2015, the job growth rate was 0.8%, among the lowest rates in America with only "10,900 total nonfarm jobs" added that year.[108] According to the Kansas Department of Labor's 2016 report, the average annual wage was $42,930 in 2015.[109] As of April 2016, the state's unemployment rate was 4.2%.[110]

The State of Kansas had a $350 million budget shortfall in February 2017.[111] In February 2017, S&P downgraded Kansas's credit rating to AA−.[112]

Nearly 90% of Kansas's land is devoted to agriculture.

By far, the most significant agricultural crop in the state is wheat. Eastern Kansas is part of the

The industrial outputs are transportation equipment, commercial and private aircraft, food processing, publishing, chemical products, machinery, apparel, petroleum, and mining.

| Rank | Business | Employees | Location | Industry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spirit AeroSystems | 12,000 | Wichita | Aviation |

| 2 | Sprint Corporation | 7,600 | Overland Park | Telecommunications |

| 3 | Textron Aviation | 6,812 | Wichita | Aviation |

| 4 | General Motors | 4,000 | Kansas City | Automotive manufacturing |

| 5 | Bombardier Aerospace

|

3,500 | Wichita | Aviation |

| 6 | Black & Veatch | 3,500 | Overland Park | Engineering Consulting |

| 7 | National Beef

|

3,500 | Liberal | Food Products |

| 8 | Tyson Foods | 3,200 | Holcomb | Food Products |

| 9 | Performance Contracting | 2,900 | Lenexa | Roofing & siding |

| 10 | National Beef

|

2,500 | Dodge City | Food Products |

The state's economy is also heavily influenced by the aerospace industry. Several large aircraft corporations have manufacturing facilities in Wichita and Kansas City, including

Major companies headquartered in Kansas include the

Kansas is also home to three major military installations: Fort Leavenworth (Army), Fort Riley (Army), and McConnell Air Force Base (Air Force). Approximately 25,000 active duty soldiers and airmen are stationed at these bases which also employ approximately 8,000 civilian DoD employees. The US Army Reserve also has the 451st Expeditionary Sustainment Command headquartered in Wichita that serves reservists and their units from around the region. The Kansas Air National Guard has units at Forbes Field in Topeka and the 184th Intelligence Wing in Wichita. The Smoky Hill Weapons Range, a detachment of the Intelligence Wing, is one of the largest and busiest bombing ranges in the nation. During World War II, Kansas was home to numerous Army Air Corps training fields for training new pilots and aircrew. Many of those airfields live on today as municipal airports.

Energy

Kansas has vast renewable resources and is a top producer of

Kansas is ranked eighth in

Kansas is also ranked eighth in US natural gas production. Production has steadily declined since the mid-1990s with the gradual depletion of the

Taxes

Tax is collected by the Kansas Department of Revenue.

Revenue shortfalls resulting from lower than expected tax collections and slower growth in personal income following a 1998 permanent tax reduction have contributed to the substantial growth in the state's debt level as bonded debt increased from $1.16 billion in 1998 to $3.83 billion in 2006. Some increase in debt was expected as the state continues with its 10-year Comprehensive Transportation Program enacted in 1999.

In 2003, Kansas had three income brackets for income tax calculation, ranging from 3.5% to 6.45%.

The state sales tax in Kansas is 6.15%. Various cities and counties in Kansas have an additional local sales tax. Except during the 2001

As of June 2004,

During his campaign for the 2010 election, Governor Sam Brownback called for a complete "phase out of Kansas's income tax".[117] In May 2012, Governor Brownback signed into law the Kansas Senate Bill Substitute HB 2117.[118] Starting in 2013, the "ambitious tax overhaul" trimmed income tax, eliminated some corporate taxes, and created pass-through income tax exemptions, he raised the sales tax by one percent to offset the loss to state revenues but that was inadequate. He made cuts to education and some state services to offset lost revenue.[119] The tax cut led to years of budget shortfalls, culminating in a $350 million budget shortfall in February 2017. From 2013 to 2017, 300,000 businesses were considered to be pass-through income entities and benefited from the tax exemption. The tax reform "encouraged tens of thousands of Kansans to claim their wages and salaries as income from a business rather than from employment."[111]

The economic growth that Brownback anticipated never materialized. He argued that it was because of "low wheat and oil prices and a downturn in aircraft sales".[117] The state general fund debt load was $83 million in fiscal year 2010 and by fiscal year 2017 the debt load sat at $179 million.[120] In 2016, Governor Brownback earned the title of "most unpopular governor in America". Only 26 percent of Kansas voters approved of his job performance, compared to 65 percent who said they did not.[121] In the summer of 2016 S&P Global Ratings downgraded Kansas's credit rating.[112] In February 2017, S&P lowered it to AA−.[112]

In February 2017, a bi-partisan coalition presented a bill that would repeal the pass-through income exemption, the "most important provisions of Brownback's overhaul", and raise taxes to make up for the budget shortfall. Brownback vetoed the bill but "45 GOP legislators had voted in favor of the increase, while 40 voted to uphold the governor's veto."[111] On June 6, 2017, a coalition of Democrats and newly elected Republicans overrode [Brownback's] veto and implemented tax increases to a level close to what it was before 2013.[117] Brownback's tax overhaul was described in a June 2017 article in The Atlantic as the United States' "most aggressive experiment in conservative economic policy".[117] The drastic tax cuts had "threatened the viability of schools and infrastructure" in Kansas.[117]

Transportation

Highways

Kansas is served by two Interstate highways with one beltway, two spur routes, and three bypasses, with over 874 miles (1,407 km) in all. The first section of Interstate in the nation was opened on Interstate 70 (I-70) just west of Topeka on November 14, 1956.[122]

I-70 is a major east–west route connecting to Denver, Colorado and Kansas City, Missouri. Cities along this route (from west to east) include Colby, Hays, Salina, Junction City, Topeka, Lawrence, Bonner Springs, and Kansas City.

I-35 is a major north–south route connecting to Oklahoma City, Oklahoma and Des Moines, Iowa. Cities along this route (from south to north) include Wichita, El Dorado, Emporia, Ottawa, and Kansas City (and suburbs).

Spur routes serve as connections between the two major routes.

U.S. Route 69 (US-69) travels south to north, from Oklahoma to Missouri. The highway passes through the eastern section of Kansas, traveling through Baxter Springs, Pittsburg, Frontenac, Fort Scott, Louisburg, and the Kansas City area.

Kansas also has the country's third largest state highway system after Texas and California. This is because of the high number of counties and county seats (105) and their intertwining.

In January 2004, the Kansas Department of Transportation (KDOT) announced the new Kansas 511 traveler information service.[123] By dialing 511, callers will get access to information about road conditions, construction, closures, detours and weather conditions for the state highway system. Weather and road condition information is updated every 15 minutes.

Interstate Highways

U.S. Routes

Aviation

The state's only major commercial (

In the state's southeastern part, people often use

Dotted across the state are smaller regional and municipal airports, including the

Rail

Up through the mid 20th century, railroads connected most cities in Kansas. During World War II, less profitable links were abandoned for scrap metal drives, then additional mileage was reduced as passenger service was halted caused by the wide spread use of automobiles and trucking on the expanding highway system.

For passenger service, currently the

For freight service, there are three

Transit

| Local transit map |

|---|

Local Transit Systems (Only systems with fixed-route services are shown)

|

Law and government

State and local politics

Executive branch: The executive branch consists of one officer and five elected officers. The governor and lieutenant governor are elected on the same ticket. The attorney general, secretary of state, state treasurer, and state insurance commissioner are each elected separately.

Political culture

Since the 1930s, Kansas has remained one of the most socially conservative states in the nation. The 1990s brought the defeat of prominent Democrats, including

19th-century state politics

Starting in 1887 Kansas women could vote in city elections and hold certain offices.[133]

20th-century state politics

Kansas was the first state to institute a system of workers' compensation (1910) and to regulate the securities industry (1911). Kansas also permitted women's suffrage in 1912, almost a decade before the federal constitution was amended to require it.[134] Suffrage in all states would not be guaranteed until ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920.

The council–manager government model was adopted by many larger Kansas cities in the years following World War I while many American cities were being run by political machines or organized crime, notably the Pendergast Machine in neighboring Kansas City, Missouri. Kansas was also at the center of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, a 1954 Supreme Court decision that banned racially segregated schools throughout the U.S., though, infamously, many Kansas residents opposed the decision, and it led to protests in Topeka after the verdict.[135]

The state backed Republican Presidential Candidates Wendell Willkie and Thomas E. Dewey in 1940 and 1944, respectively, breaking ranks with the majority of the country in the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Kansas also supported Dewey in 1948 despite the presence of incumbent president Harry S. Truman, who hailed from Independence, Missouri, approximately 15 miles (24 km) east of the Kansas–Missouri state line. After Roosevelt carried Kansas in 1936, only one Democrat has won the state since, Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964.

21st-century state politics

| Party | Number of voters | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | 869,391 | 44.48% | |

Unaffiliated

|

554,236 | 28.35% | |

| Democratic | 506,640 | 25.92% | |

| Libertarian | 24,088 | 1.23% | |

| Total | 1,954,355 | 100.00% | |

In 2008, Democrat Governor Kathleen Sebelius vetoed permits for the construction of new coal-fired energy plants in Kansas, saying: "We know that greenhouse gases contribute to climate change. As an agricultural state, Kansas is particularly vulnerable. Therefore, reducing pollutants benefits our state not only in the short term—but also for generations of Kansans to come."[137] However, shortly after Mark Parkinson became governor in 2009 upon Sebelius's resignation to become Secretary of U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Parkinson announced a compromise plan to allow construction of a coal-fired plant.

In 2010, Republican Sam Brownback was elected governor with 63 percent of the state vote. He was sworn in as governor in 2011, Kansas's first Republican governor in eight years. Brownback had established himself as a conservative member of the U.S. Senate in years prior, but made several controversial decisions after becoming governor, leading to a 23% approval rating among registered voters – the lowest of any governor in the United States.[138] In May 2011, much to the opposition of art leaders and enthusiasts in the state, Brownback eliminated the Kansas Arts Commission, making Kansas the first state without an arts agency.[139] In July 2011, Brownback announced plans to close the Lawrence branch of the Kansas Department of Social and Rehabilitation Services as a cost-saving measure. Hundreds rallied against the decision.[140] Lawrence City Commission later voted to provide the funding needed to keep the branch open.[141]

Democrat Laura Kelly defeated former Secretary of State of Kansas Kris Kobach in the 2018 election for Governor with 48.0% of the vote.[142][143]

In August 2022, Kansas voters rejected the controversial

In a 2020 study, Kansas was ranked as the 13th hardest state for citizens to vote in.[145]

National politics

Parts of this article (those related to Section) need to be updated. The reason given is: The margin and % numbers are inaccurate for a few elections.. (February 2023) |

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 771,406 | 56.00% | 570,323 | 41.40% | 35,755 | 2.60% |

| 2016 | 671,018 | 56.03% | 427,005 | 35.66% | 99,547 | 8.31% |

| 2012 | 689,809 | 59.59% | 439,908 | 38.00% | 27,815 | 2.40% |

| 2008 | 699,655 | 56.48% | 514,765 | 41.55% | 24,453 | 1.97% |

| 2004 | 736,456 | 62.00% | 434,993 | 36.62% | 16,307 | 1.37% |

| 2000 | 622,332 | 58.04% | 399,276 | 37.24% | 50,608 | 4.72% |

| 1996 | 583,245 | 54.29% | 387,659 | 36.08% | 103,396 | 9.62% |

| 1992 | 449,951 | 38.88% | 390,434 | 33.74% | 316,851 | 27.38% |

| 1988 | 554,049 | 55.79% | 422,636 | 42.56% | 16,359 | 1.65% |

| 1984 | 677,296 | 66.27% | 333,149 | 32.60% | 11,546 | 1.13% |

| 1980 | 566,812 | 57.85% | 326,150 | 33.29% | 86,833 | 8.86% |

| 1976 | 502,752 | 52.49% | 430,421 | 44.94% | 24,672 | 2.58% |

| 1972 | 619,812 | 67.66% | 270,287 | 29.50% | 25,996 | 2.84% |

| 1968 | 478,674 | 54.84% | 302,996 | 34.72% | 91,113 | 10.44% |

| 1964 | 386,579 | 45.06% | 464,028 | 54.09% | 7,294 | 0.85% |

| 1960 | 561,474 | 60.45% | 363,213 | 39.10% | 4,138 | 0.45% |

| 1956 | 566,878 | 65.44% | 296,317 | 34.21% | 3,048 | 0.35% |

| 1952 | 616,302 | 68.77% | 273,296 | 30.50% | 6,568 | 0.73% |

| 1948 | 423,039 | 53.63% | 351,902 | 44.61% | 13,878 | 1.76% |

| 1944 | 442,096 | 60.25% | 287,458 | 39.18% | 4,222 | 0.58% |

| 1940 | 489,169 | 56.86% | 364,725 | 42.40% | 6,403 | 0.74% |

| 1936 | 397,727 | 45.95% | 464,520 | 53.67% | 3,267 | 0.38% |

| 1932 | 349,498 | 44.13% | 424,204 | 53.56% | 18,276 | 2.31% |

| 1928 | 513,672 | 72.02% | 193,003 | 27.06% | 6,525 | 0.91% |

| 1924 | 407,671 | 61.54% | 156,319 | 23.60% | 98,464 | 14.86% |

| 1920 | 369,268 | 64.75% | 185,464 | 32.52% | 15,586 | 2.73% |

| 1916 | 277,658 | 44.09% | 314,588 | 49.95% | 37,567 | 5.96% |

| 1912 | 74,845 | 20.47% | 143,663 | 39.30% | 147,052 | 40.23% |

| 1908 | 197,216 | 52.46% | 161,209 | 42.88% | 17,521 | 4.66% |

| 1904 | 212,955 | 64.81% | 86,174 | 26.23% | 29,432 | 8.96% |

| 1900 | 185,955 | 52.56% | 162,601 | 45.96% | 5,210 | 1.47% |

| 1896 | 159,345 | 47.63% | 171,675 | 51.32% | 3,527 | 1.05% |

| 1892 | 157,241 | 48.40% | 0 | 0.00% | 167,664 | 51.60% |

| 1888 | 182,904 | 55.23% | 102,745 | 31.03% | 45,500 | 13.74% |

| 1884 | 154,406 | 58.08% | 90,132 | 33.90% | 21,310 | 8.02% |

| 1880 | 121,549 | 60.40% | 59,801 | 29.72% | 19,886 | 9.88% |

| 1876 | 78,324 | 63.10% | 37,902 | 30.53% | 7,908 | 6.37% |

| 1872 | 66,805 | 66.46% | 32,970 | 32.80% | 737 | 0.73% |

| 1868 | 30,027 | 68.82% | 13,600 | 31.17% | 3 | 0.01% |

| 1864 | 17,089 | 79.19% | 3,836 | 17.78% | 655 | 3.04% |

The state's current delegation to the

Historically, Kansas has been strongly Republican, dating from the

The only non-Republican presidential candidates Kansas has given its electoral vote to are Populist

Abilene was the boyhood home to Republican president Dwight D. Eisenhower, and he maintained lifelong ties to family and friends there. Kansas was the adult home of two losing Republican candidates (Governor Alf Landon in 1936 and Senator Bob Dole in 1996).

The New York Times reported in September 2014 that as the Democratic candidate for Senator has tried to drop out of the race, independent Greg Orman has attracted enough bipartisan support to seriously challenge the reelection bid of Republican Pat Roberts:

- Kansas politics have been roiled in recent years. The rise of the Tea Party and the election of President Obama have prompted Republicans to embrace a purer brand of conservatism and purge what had long been a robust moderate wing from its ranks. Mr. Roberts has sought to adapt to this new era, voting against spending bills that included projects for the state that he had sought.[148]

State laws

The

On May 12, 2022, Gov. Laura Kelly signed legislation (Senate Bill 84) that legalizes sports betting in the state, making Kansas the 35th state to approve sports wagering in the US. This would give the four state-owned casinos the right to partner with online bookmakers and up to 50 retailers, including gas stations and restaurants, to engage in sports betting.[151]

Education

Education in Kansas is governed at the primary and secondary school level by the

Twice since 1999 the Board of Education has approved changes in the state science curriculum standards that encouraged the teaching of intelligent design. Both times, the standards were reversed after changes in the composition of the board in the next election.

Culture

Music

The rock band Kansas was formed in the state capital of Topeka, the hometown of several of the band's members.

Joe Walsh, guitarist for the famous rock band the Eagles, was born in Wichita. Danny Carey, drummer for the band Tool, was raised in Paola.

Singers from Kansas include Leavenworth native Melissa Etheridge, Sharon native Martina McBride, Chanute native Jennifer Knapp (whose first album was titled Kansas), Kansas City native Janelle Monáe, Prairie Village native Joyce DiDonato, and Liberal native Jerrod Niemann.

The state anthem is the American classic Home on the Range, written by Kansan Brewster Higley. Another song, the official state march adopted by the Kansas Legislature in 1935 is called The Kansas March, which features the lyrics, "Blue sky above us, silken strands of heat, Rim of the far horizon, where earth and heaven meet, Kansas as a temple, stands in velvet sod, Shrine which the sunshine, sanctifies to God."[152]

Literature

The state's most famous appearance in literature was as the home of Dorothy Gale, the main character in the novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House on the Prairie, published in 1935, is another well-known tale about Kansas.

Kansas was also the setting of the 1965 best-seller

The fictional town of

The science fiction novella A Boy and His Dog, as well as the film based on it,[153] take place in post-apocalyptic Topeka.

The winner of the 2011 Newbery Medal for excellence in children's literature, Moon Over Manifest, tells the story of a young and adventurous girl named Abilene who is sent to the fictional town of Manifest, Kansas, by her father in the summer of 1936. It was written by Kansan Clare Vanderpool.

Art

Kansas is home to a number of art museums. The Wichita Art Museum collection focuses on American art.[154] The Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art in Overland Park exhibits artists of national and international recognition.[155] The Spencer Museum of Art, at University of Kansas in Lawrence, has a diverse permanent collection and Ingrid & J.K. Lee Study Center as an education space.[156]

Film

The first film theater in Kansas was the Patee Theater in Lawrence. Most theaters at the time showed films only as part of vaudeville acts but not as an exclusive and stand alone form of entertainment. Though the Patee family had been involved in vaudeville, they believed films could carry the evening without other variety acts, but to show the films it was necessary for the Patee's to establish a generating plant (back in 1903 Lawrence was not yet fully electrified). The Patee Theater was one of the first of its kind west of the Mississippi River. The specialized equipment like the projector came from New York City.[157]

Kansas has been the setting of many award-winning and popular American films, as well as being the home of some of the oldest operating cinemas in the world. The Plaza Cinema in Ottawa, Kansas, located in the northeastern portion of the state, was built on May 22, 1907, and it is listed by the

- As was the case with the novel, The Wizard of Oz was a young girl who lived in Kansas with her aunt and uncle. The line, "We're not in Kansas anymore", has entered into the English lexicon as a phrase describing a wholly new or unexpected situation.[161]

- The 1967 feature film In Cold Blood, like the book on which it was based, was set in various locations across Kansas. Many of the scenes in the film were filmed at the exact locations where the events profiled in the book took place. A 1996 TV miniseries was also based on the book.

- The 1988 film Kansas starred Andrew McCarthy as a traveler who met up with a dangerous wanted drifter played by Matt Dillon.

- The 2005 film Capote, for which Philip Seymour Hoffman was awarded the Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of the title character, profiled the author as he traveled across Kansas while writing In Cold Blood (although most of the film itself was shot in the Canadian province of Manitoba).

- The setting of The Day After, a 1983 made-for-television movie about a fictional nuclear attack, was the city of Lawrence.

- Due to the super hero Superman growing up in the fictional Smallville, Kansas, multiple films featuring the super hero have been entirely or at least partially set in Kansas including Superman (1978), Superman III (1983), Man of Steel (2013), Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016), and Justice League (2017).

- The 2012 film Looper is set in Kansas.

- The 1973 film Saint Joseph, Missouri.

- Scenes of the 1996 film Mars Attacks! took place in the fictional town of Perkinsville. Scenes taking place in Kansas were filmed in Burns, Lawrence, and Wichita.

- The 2007 film The Lookout is set mostly in Kansas (although filmed in Canada). Specifically two locations; Kansas City and the fictional town of Noel, Kansas.[162]

- The 2012 documentary The Gridiron was filmed at The University of Kansas

- The 2014 ESPN documentary No Place Like Home was filmed in Lawrence and the countryside of Douglas County, Kansas

- The 2017 film Topeka and Junction City.

- The 2017 documentary When Kings Reigned was filmed in Lawrence.

- The 2019 film Brightburn took place in the fictional town of Brightburn. As is evident with scenes in the film depicting mountains (Kansas has no mountain ranges), it was filmed in Georgia instead of in Kansas.

Television

- The protagonist brothers of the 2005 TV show Supernaturalhail from Lawrence, with the city referenced numerous times on the show.

- Most of the second season of the TV Series Prison Break had scenes that took place in Kansas. Specifically the towns of Ness City and Tribune as the character T–Bag searches for his for his ex-girlfriend who turned him in to the police. A season 1 episode also briefly took place in Topeka.

- 2006 TV series Jericho was based in the fictitious town of Jericho, Kansas, surviving post-nuclear America.

- Early seasons of Smallville, about Superman as a teenager, were based in a fictional town of Smallville, Kansas. Unlike most other adaptations of the Superman story, the series also places the fictional city of Metropolis in western Kansas, a few hours from Smallville.

- Gunsmoke, a radio series western, ran from 1952 to 1961, took place in Dodge City, Kansas.

- Gunsmoke, television series, the longest running prime time show of the 20th century, ran from September 10, 1955, to March 31, 1975, for a total of 635 episodes.

- The 2009 Overland Park, a suburb of Kansas City.

Sports

Professional

| Team | Sport | League | City |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sporting Kansas City | Soccer | Major League Soccer | Kansas City |

| Sporting Kansas City II | Soccer | MLS Next Pro | Kansas City |

| Kansas City Monarchs | Baseball | American Association

|

Kansas City |

| Garden City Wind | Baseball | Pecos League | Garden City |

| Kaw Valley FC | Soccer | USL League Two | Lawrence, and Topeka |

| Salina Liberty | Indoor football

|

Champions Indoor Football | Salina |

| Southwest Kansas Storm | Indoor football | Champions Indoor Football | Dodge City

|

| Topeka Tropics | Indoor football | Champions Indoor Football | Topeka |

| Wichita Thunder | Ice hockey | ECHL | Wichita |

| Wichita Wind Surge | Baseball | Double-A Central

|

Wichita |

Sporting Kansas City, who have played their home games at

Historically, Kansans have supported the

Some Kansans, mostly from the westernmost parts of the state, support the professional sports teams of Denver, particularly the Denver Broncos of the NFL.

Two major

History

The history of professional sports in Kansas probably dates from the establishment of the

In 1887, the Western League was dominated by a reorganized Topeka team called the

The first night game in the history of professional baseball was played in Independence on April 28, 1930, when the Muscogee (Oklahoma) Indians beat the Independence Producers 13–3 in a minor league game sanctioned by the Western League of the Western Baseball Association with 1,500 fans attending the game. The permanent lighting system was first used for an exhibition game on April 17, 1930, between the Independence Producers and House of David semi-professional baseball team of Benton Harbor, Michigan with the Independence team winning 9–1 before a crowd of 1,700 spectators.[166]

College

The governing body for intercollegiate sports in the United States, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), was headquartered in Johnson County, Kansas from 1952 until moving to Indianapolis in 1999.[167][168]

NCAA Division I schools

While there are no franchises of the four major professional sports within the state, many Kansans are fans of the state's major college sports teams, especially the Jayhawks of the University of Kansas (KU), and the Wildcats of Kansas State University (KSU or "K-State"). The teams are rivals in the Big 12 Conference.

Both KU and K-State have tradition-rich programs in men's basketball. The Jayhawks are a perennial national power, ranking first in all-time victories among NCAA programs. The Jayhawks have won six national titles, including NCAA tournament championships in 1952, 1988, 2008, and 2022. They also were retroactively awarded national championships by the

Conversely, success on the

Wichita State University, which also fields teams (called the Shockers) in Division I of the NCAA, is best known for its baseball and basketball programs. In baseball, the Shockers won the College World Series in 1989. In men's basketball, they appeared in the Final Four in 1965 and 2013, and entered the 2014 NCAA tournament unbeaten. The school also fielded a football team from 1897 to 1986. The Shocker football team is tragically known for a plane crash in 1970 that killed 31 people, including 14 players.

NCAA Division II schools

Notable success has also been achieved by the state's smaller schools in football. Pittsburg State University, an NCAA Division II participant, has claimed four national titles in football, two in the NAIA and most recently the 2011 NCAA Division II national title. Pittsburg State became the winningest NCAA Division II football program in 1995. PSU passed Hillsdale College at the top of the all-time victories list in the 1995 season on its march to the national runner-up finish. The Gorillas, in 96 seasons of intercollegiate competition, have accumulated 579 victories, posting a 579–301–48 overall mark.

Washburn University, in Topeka, won the NAIA Men's Basketball Championship in 1987. The Fort Hays State University men won the 1996 NCAA Division II title with a 34–0 record, and the Washburn women won the 2005 NCAA Division II crown. St. Benedict's College (now Benedictine College), in Atchison, won the 1954 and 1967 Men's NAIA Basketball Championships.

The Kansas Collegiate Athletic Conference has its roots as one of the oldest college sport conferences in existence and participates in the NAIA and all ten member schools are in the state of Kansas. Other smaller school conferences that have some members in Kansas are the Mid-America Intercollegiate Athletics Association the Midlands Collegiate Athletic Conference, the Midwest Christian College Conference, and the Heart of America Athletic Conference. Many junior colleges also have active athletic programs.

Junior colleges

The

High school

The Kansas State High School Activities Association (KSHSAA) is the organization which oversees interscholastic competition in the state of Kansas at the high school level. It oversees both athletic and non-athletic competition, and sponsors championships in several sports and activities.

See also

- Index of Kansas-related articles

- Outline of Kansas

- List of Kansas landmarks

- List of people from Kansas

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Kansas

- USS Kansas, 2 ships

Notes

- Wichita metropolitan areais the largest centered in the state.

- ^ a b Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988.

References

- ^ Riney-Kehrberg, Pamela. "Wholesome, Home-Baked Goodness: Kansas, the Wheat State" (PDF). Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains (Spring 2011). Kansas State Historical Society: 60–69.

- ^ "New vanity tag rule spurs drivers' creativity".

- ^ a b c Geography, US Census Bureau. "State Area Measurements and Internal Point Coordinates". Archived from the original on March 16, 2018. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ Perlman, Howard. "Area of each state that is water". Archived from the original on June 25, 2016.

- ^ a b "Kansas Geography from NETSTATE". Archived from the original on June 4, 2016.

- ^ a b "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ a b "Median Annual Household Income". The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ "Governor's Signature Makes English the Official Language of Kansas". US English. May 11, 2007. Archived from the original on July 10, 2007. Retrieved August 6, 2008.

- ^ "Kansas". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Current Lists of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas and Delineations". Archived from the original on January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Kansas Historical Quarterly—A Review of Early Navigation on the Kansas River—Kansas Historical Society". Kshs.org. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ "Kansas history page". Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ISBN 0-403-09921-8

- ^ John Koontz, p.c.

- ^ "Today in History: January 29". Memory.loc.gov. Archived from the original on July 27, 2010. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ "Kansas Quick Facts". governor.ks.gov. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ISBN 978-1-250-07148-4.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian. "How Dodge City Became a Symbol of Frontier Lawlessness". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ "Kansas Agriculture". Kansas Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on September 20, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ "2020 Census" (PDF). Census.gov. April 26, 2021.

- ^ "Mount Sunflower—Kansas, United States • peakery". April 3, 2011. Archived from the original on April 3, 2011.

- OCLC 53019644.

- ^ Rankin, Robert. 2005. "Quapaw". In Native Languages of the Southeastern United States, eds. Heather K. Hardy and Janine Scancarelli. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, p. 492.

- ^ Connelley, William E. 1918. "Indians Archived February 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine". A Standard History of Kansas and Kansans, ch. 10, vol. 1.

- ^ Cazorla, Frank, G. Baena, Rosa, Polo, David, Reder Gadow, Marion (2019) Luis de Unzaga (1717–1793) Pioneer in the birth of the United States and in the liberalism. Foundation Malaga

- ^ Partin, John W. Partin (1983). "A Brief History of Fort Leavenworth" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ Jones, Gray Ghosts and Rebel Riders Holt & Co. 1956, p. 76

- ^ "Less of Oratory and More Work Novel Platform." Alliance, Ohio: The Alliance Review and Leader, April 21, 1922.

- ^ "Mrs. W.D. Mowry Dies." Emporia, Kansas: The Emporia Gazette, August 2, 1923, p. 5.

- ^ "Pioneer Woman Candidate for Governor Dies: Mrs. W.D. Mowry on Republican Ticket in Primary Last Year." Concordia, Kansas: Concordia Blade-Empire, August 2, 1923, front page.

- ^ "The Dust Bowl | Great Depression and World War II, 1929-1945 | U.S. History Primary Source Timeline | Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ "Kansas Land Area County Rank". www.usa.com.

- ^ "Kansas Is Flatter Than a Pancake". Improbable.com. Archived from the original on July 30, 2010. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ "Highest, Lowest, and Mean Elevations in the United States". infoplease.com. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ "Fracas over Kansas pancake flap". Geotimes.org. Archived from the original on January 24, 2004. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ "Kansas". National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 17, 2006. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Kansas Natural Heritage Inventory: Rare plants and animals, and natural communities". Kansas Biological Survey. February 12, 2013. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Kansas, Natural Heritage Inventory (January 9, 2014). "Rare Vertebrates Kansas" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Kansas, Natural Heritage Inventory (January 9, 2014). "Rare Vertebrates of Kansas" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ K-State Research, and Extension. "Native Plants" (PDF). www.johnson.k-state.edu.

- ^ "Kansas Wildflowers and Grasses". www.kswildflower.org. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ "Kansas Hardiness Zones Map - 2023". Plantmaps. Archived from the original on January 17, 2024. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ^ "Annual Average Number of Tornadoes, 1953–2004". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on October 16, 2011. Retrieved October 25, 2006.

- ^

- "Concordia Weather—Kansas—Average Temperatures and Rainfall". Country Studies US. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- "Dodge City Weather—Kansas—Average Temperatures and Rainfall". Country Studies US. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- "Goodland Weather—Kansas—Average Temperatures and Rainfall". Country Studies US. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- "Topeka Weather—Kansas—Average Temperatures and Rainfall". Country Studies US. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- "Wichita Weather—Kansas—Average Temperatures and Rainfall". Country Studies US. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Daniel C. "KS extinct locations". Archived from the original on December 6, 2012.

- ^ "Population Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved August 4, 2022.[dead link]

- ^ "Births: Final Data for 2013" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. CDC. January 15, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ "Births: Final Data for 2014" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. CDC. December 23, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ "Births: Final Data for 2015" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. CDC. January 5, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ "data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ "US Health Map". Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. University of Washington. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ "Kansas: Life Expectancy". Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ "Mortality in the United States, 2019" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-4671-1043-3.

- ^ N/A. "Wichita (city), Kansas".

- ^ a b c "Go Wichita Convention and Visitors Bureau". Gowichita.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- ^ "Annual estimates of the population through July 1, 2006". Population Estimates. Census Bureau, Population Division. June 28, 2007. Archived from the original on December 6, 2006.

- ^ "The Blackwell Tornado of 25 May 1955". NWS Norman, Oklahoma. June 13, 2006. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved January 28, 2007.

- ^ McCORMICK, PETER J. "THE 1992 SECESSION MOVEMENT IN SOUTHWEST KANSAS". digitalcommons.unl.edu/.

- ^ "QuickFacts Kansas; UNITED STATES". 2018 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 3, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ "Cumulative Estimates of the Components of Population Change for the United States, Regions and States: April 1, 2000, to July 1, 2006", Population Estimates, US: Census Bureau, Population Division, December 22, 2006, NST-EST2006-04, archived from the original on September 16, 2004,

Kansas population has increased at a decreasing rate, reducing the number of congressmen from 5 to 4 in 1992 (Congressional Redistricting Act, eff. 1992).

- ^ "Immigrants in Kansas" (PDF).

- ISBN 9780143112334.

- ^ "Population and Population Centers by State". U.S. Census Bureau. 2000. Archived from the original on February 23, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brown, Corie (April 26, 2018). "Rural Kansas is dying. I drove 1,800 miles to find out why". New Food Economy. Archived from the original on May 17, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ^ "2007–2022 PIT Counts by State".

- ^ "The 2022 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress" (PDF).

- ^ "Historical Population Change Data (1910–2020)". Census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Kansas". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ "Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For The United States, Regions, Divisions, and States". July 25, 2008. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008.

- ^ Kansas Statistical Abstract. "Population in Kansas and the U.S., by Race/ Page 7" (PDF). ipsr.ku.edu.

- U.S. Census Bureau.

- U.S. Census Bureau. August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "Kansas—Social demographics". American Community Survey Office. 2006. Archived from the original on September 10, 2004. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ "Czechs in Kansas - Kansapedia".

- ^ Painter, Nell Irvin. Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction. United States, W. W. Norton, 1992. p.146

- ^ "Asian Americans in Kansas - Kansapedia".

- ^ "Births: Final Data for 2013" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. CDC. January 15, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ "Births: Final Data for 2014" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. CDC. December 23, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ "Births: Final Data for 2015" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. CDC. January 5, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ "data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.cdc.gov. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ Exner, Rich (June 3, 2012). "Americans under age 1 now mostly minorities, but not in Ohio: Statistical Snapshot". The Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on July 14, 2016.

- ^ "Languages—Kansas". City-data.com. Retrieved September 4, 2019.

- ^ Pew Research Center, Religious Landscape Study: Religious composition of adults in Kansas Archived May 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine (2014).

- ^ "The Association of Religion Data Archives | State Membership Report". www.thearda.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ^ "2020 Congregational Membership". www.thearda.com. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ^ "PRRI – American Values Atlas". ava.prri.org. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ISBN 1-879448-11-4.

- ^ "Westboro Baptist protests at Atlanta HBCU graduation ceremonies". 11Alive.com. May 19, 2019. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ "Anti-LGBTQ hate groups on the rise in U.S., report warns". NBC News. March 30, 2020. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ "Westboro Baptist Church". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on March 6, 2011.

- ^ 2017 Kansas Economic Report Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ 2020 Economic Forecast Archived November 16, 2019, at the Wayback Machine Greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Kansas". www.census.gov.

- ^ "U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)". Bea.gov. 2016. Archived from the original on July 7, 2010. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ^ Abouhalkah, Yael T. (November 30, 2015), Kansas has low but misleading unemployment rate under Gov. Sam Brownback, archived from the original on February 27, 2017, retrieved February 26, 2017

- ^ Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) OES Home 2016 Kansas Wage Survey (PDF), 2016, archived (PDF) from the original on January 24, 2017, retrieved February 26, 2017

- ^ "Local Area Unemployment Statistics". Bls.gov. Archived from the original on August 28, 2010. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c Max Ehrenfreund (February 22, 2017), "Republicans' 'real-live experiment' with Kansas's economy survives a revolt from their own party", The Washington Post, archived from the original on February 24, 2017, retrieved February 25, 2017

- ^ a b c Blinder, Alan (February 22, 2017), "Kansas Lawmakers Uphold Governor's Veto of Tax Increases", The New York Times, retrieved February 25, 2017

- ^ "Kansas Department of Commerce—Official Website—Economic Overview Charts". Kansascommerce.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ "Publication 1700". Kansas Department of Revenue. Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ "Streamlined Sales Tax—Kansas". Streamlined Sales Tax. Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Berman, Russell (June 7, 2017). "The Death of Kansas's Conservative Experiment". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on June 12, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ "Senate Substitute for HB 2117 by Committee on Taxation—Reduction of income tax rates for individuals and determination of income tax credits; severance tax exemptions; homestead property tax refunds; food sales tax refunds". Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ Editorial Board (April 13, 2013). "Editorial: Louisiana's lawmakers realize what Missouri's don't: Income tax cuts are suicidal". Archived from the original on August 20, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ Carpenter, Tim. "Kansas state government bond debt surges $2 billion since 2010". The Topeka Capital. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "America's Most (and Least) Popular Governors—Morning Consult". Morning Consult. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ I-70—the First Open Interstate, Kansas Department of Transportation, July 24, 2014, archived from the original on October 26, 2016, retrieved October 7, 2016

- ^ "KDOT Launches New Traveler Information Service" (Press release). Kansas Department of Transportation. January 22, 2004. Archived from the original on January 18, 2006. Retrieved July 14, 2006.

- ^ "Manhattan Airport Official Site". Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2010.

- ^ "Amtrak Southwest Chief". Amtrak. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ^ "Wichita Returns to the Amtrak Map". Amtrak. April 18, 2016. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ^ Ben Kuebrich, Amtrak May End Passenger Rail Service in West Kansas. Moran: "Amtrak Is Not Doing Its Job", KCUR. June 28, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ "Heartland Flyer Extension". storymaps.arcgis.com. Amtrak Connect Us. September 17, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ "Could Kansans soon hop a train to Texas? Billions in federal funding might mean yes". Topeka Capital-Journal. January 30, 2023. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023.

- ^ "Kansas State Railroad Map 2017" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- ^ "Vote by Kansas School Board Favors Evolution's Doubters". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013.

- ^ "Kansas Lawmakers Set Minimum Marriage Age to 15". Fox News. May 5, 2006. Archived from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Society, Kansas State Historical (1912). Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society.

- ISBN 978-0-252-01005-7.

- ^ "Civil Rights Movement". NCpedia. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "Voter Registration Statistics". Kansas Secretary of State. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ "Kansas Governor Rejects Two Coal-Fired Power Plants". Ens-newswire.com. March 21, 2008. Archived from the original on February 2, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ "Here Are America's Least (and Most) Popular Governors". MorningConsultant.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Kansas governor eliminates state's art funding". Los Angeles Times. May 31, 2011. p. m. Archived from the original on September 17, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ Hittle, Shaun (July 16, 2011). "Hundreds rally against closing SRS office". ljworld.com. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ "Lawrence City Commission approves funding for SRS office". ljworld.com. August 9, 2011. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Mitch (November 6, 2018). "Laura Kelly, a Kansas Democrat, Tops Kobach in Governor's Race". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Shorman, Jonathan; Woodall, Hunter (November 8, 2018). "Democrat Laura Kelly defeats Kris Kobach to become Kansas' next governor". The Wichita Eagle. Material. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Kansas abortion vote: Major victory for pro-choice groups". BBC News. August 3, 2022. Retrieved October 30, 2022.

- S2CID 225139517.

- ^ Leip, David. "Presidential General Election Results Comparison – Kansas". US Election Atlas. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ "2008 Election Results—Kansas". CNN. Archived from the original on November 7, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ Jonathan Martin, "National G.O.P. Moves to Take Over Campaign of Kansas Senator", New York Times September 4, 2014 Archived September 11, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Liquor Licensee and Supplier Information". Alcoholic Beverage Control, Kansas Department of Revenue. Archived from the original on December 8, 2006. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ^ "History of Alcoholic Beverages in Kansas". Alcoholic Beverage Control, Kansas Department of Revenue. 2000. Archived from the original on January 17, 2007. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ^ "Kansas Legalizes Online and Retail Sports Wagering". casinoreviews.net. May 16, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "Kansas March—Kansapedia—Kansas Historical Society". www.kshs.org.

- ^ Eder, Richard (June 17, 1976). "A Boy and His Dog". The New York Times.

- ^ "The Best Art Museum in Every U.S. State (slide 44 of 51)". Art & Object. June 27, 2023. Archived from the original on February 17, 2024. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- ^ Thorson, Alice (April 24, 2017). "A 'Game-Changing Asset'". Flatland. Archived from the original on December 1, 2023. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ Denesha, Julie (January 24, 2023). "Spencer Museum of Art's new redesign brings a 'broader range of voices' to Lawrence". KCUR - Kansas. Archived from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ISBN 9780826217493.

- ^ "Guinness World Records: Kansas venue is world's oldest cinema". Kansas City Star. March 8, 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ "Oldest purpose-built cinema in operation". Guinness World Records. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ "Data". npgallery.nps.gov. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ "PBR: Toto—we're not in Kansas any more ..." BBC Newsnight. December 9, 2009. Archived from the original on February 11, 2014.

- ^ "The Lookout" (PDF). dailyscript.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 12, 2013.