Karl Kraus (writer)

Karl Kraus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 28 April 1874 Jičín, Kingdom of Bohemia, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 12 June 1936 (aged 62) Vienna, Austria |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | University of Vienna |

| Genre | Satire |

Karl Kraus (28 April 1874 – 12 June 1936)[1] was an Austrian writer and journalist, known as a satirist, essayist, aphorist, playwright and poet. He directed his satire at the press, German culture, and German and Austrian politics. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature three times.[2]

Biography

Early life

Kraus was born into the wealthy Jewish family of Jacob Kraus, a papermaker, and his wife Ernestine, née Kantor, in Jičín, Kingdom of Bohemia, Austria-Hungary (now the Czech Republic). The family moved to Vienna in 1877. His mother died in 1891.

Kraus enrolled as a law student at the University of Vienna in 1892. Beginning in April of the same year, he began contributing to the paper Wiener Literaturzeitung, starting with a critique of Gerhart Hauptmann's The Weavers. Around that time, he unsuccessfully tried to perform as an actor in a small theater. In 1894, he changed his field of studies to philosophy and German literature. He discontinued his studies in 1896. His friendship with Peter Altenberg began about this time.

Career

Before 1900

In 1896, Kraus left university without a diploma to begin work as an actor, stage director and performer, joining the

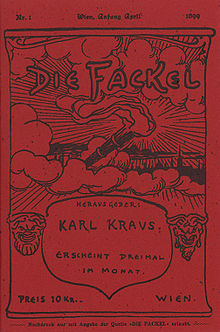

On 1 April 1899, Kraus renounced Judaism, and in the same year he founded his own magazine,

1900–1909

In 1901 Kraus was sued by Hermann Bahr and Emmerich Bukovics, who felt they had been attacked in Die Fackel. Many lawsuits by various offended parties followed in later years. Also in 1901, Kraus found out that his publisher, Moriz Frisch, had taken over his magazine while he was absent on a months-long journey. Frisch had registered the magazine's front cover as a trademark and published the Neue Fackel (New Torch). Kraus sued and won. From that time, Die Fackel was published (without a cover page) by the printer Jahoda & Siegel.

While Die Fackel at first resembled journals like Die Weltbühne, it increasingly became a magazine that was privileged in its editorial independence, thanks to Kraus's financial independence. Die Fackel printed what Kraus wanted to be printed. In its first decade, contributors included such well-known writers and artists as Peter Altenberg, Richard Dehmel, Egon Friedell, Oskar Kokoschka, Else Lasker-Schüler, Adolf Loos, Heinrich Mann, Arnold Schönberg, August Strindberg, Georg Trakl, Frank Wedekind, Franz Werfel, Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Oscar Wilde. After 1911, however, Kraus was usually the sole author. Kraus's work was published nearly exclusively in Die Fackel, of which 922 irregularly issued numbers appeared in total. Authors who were supported by Kraus include Peter Altenberg, Else Lasker-Schüler, and Georg Trakl.

Die Fackel targeted corruption, journalists and brutish behaviour. Notable enemies were

In 1902, Kraus published Sittlichkeit und Kriminalität (Morality and Criminal Justice), for the first time commenting on what was to become one of his main preoccupations: he attacked the general opinion of the time that it was necessary to defend sexual morality by means of criminal justice (Der Skandal fängt an, wenn die Polizei ihm ein Ende macht, The Scandal Starts When the Police Ends It).[3] Starting in 1906, Kraus published the first of his aphorisms in Die Fackel; they were collected in 1909 in the book Sprüche und Widersprüche (Sayings and Gainsayings).

In addition to his writings, Kraus gave numerous highly influential public readings during his career, put on approximately 700 one-man performances between 1892 and 1936 in which he read from the dramas of Bertolt Brecht, Gerhart Hauptmann, Johann Nestroy, Goethe, and Shakespeare, and also performed Offenbach's operettas, accompanied by piano and singing all the roles himself. Elias Canetti, who regularly attended Kraus's lectures, titled the second volume of his autobiography "Die Fackel" im Ohr ("The Torch" in the Ear) in reference to the magazine and its author. At the peak of his popularity, Kraus's lectures attracted four thousand people, and his magazine sold forty thousand copies.[4]

In 1904, Kraus supported Frank Wedekind to make possible the staging in Vienna of his controversial play Pandora's Box;[5] the play told the story of a sexually enticing young dancer who rises in German society through her relationships with wealthy men but later falls into poverty and prostitution.[6] These plays' frank depiction of sexuality and violence, including lesbianism and an encounter with Jack the Ripper,[7] pushed against the boundaries of what was considered acceptable on the stage at the time. Wedekind's works are considered among the precursors of expressionism, but in 1914, when expressionist poets like Richard Dehmel began producing war propaganda, Kraus became a fierce critic of them.[4][5]

In 1907, Kraus attacked his erstwhile benefactor Maximilian Harden because of his role in the Eulenburg trial in the first of his spectacular Erledigungen (Dispatches).[citation needed]

1910–1919

After 1911, Kraus was the sole author of most issues of Die Fackel.

One of Kraus's most influential satirical-literary techniques was his clever

After an obituary for

Kraus's masterpiece is generally considered to be the massive satirical play about the

Also in 1919, Kraus published his collected war texts under the title Weltgericht (World Court of Justice). In 1920, he published the satire Literatur oder man wird doch da sehn (Literature, or You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet) as a reply to Franz Werfel's Spiegelmensch (Mirror Man), an attack against Kraus.[citation needed]

1920–1936

During January 1924, Kraus started a fight against Imre Békessy, publisher of the tabloid Die Stunde (The Hour), accusing him of extorting money from restaurant owners by threatening them with bad reviews unless they paid him. Békessy retaliated with a libel campaign against Kraus, who in turn launched an Erledigung with the catchphrase "Hinaus aus Wien mit dem Schuft!" ("Throw the scoundrel out of Vienna!"). In 1926, Békessy indeed fled Vienna to avoid arrest. Békessy achieved some later success when his novel Barabbas was the monthly selection of an American book club.[citation needed]

A peak in Kraus's political commitment was his sensational attack in 1927 on the powerful Vienna police chief

In 1928, the play Die Unüberwindlichen (The Insurmountables) was published. It included allusions to the fights against Békessy and Schober. During that same year, Kraus also published the records of a lawsuit Kerr had filed against him after Kraus had published Kerr's war poems in Die Fackel (Kerr, having become a pacifist, did not want his earlier enthusiasm for the war exposed). In 1932, Kraus translated Shakespeare's sonnets.

Kraus supported the Social Democratic Party of Austria from at least the early 1920s,[4] but in 1934, hoping Engelbert Dollfuss could prevent Nazism from engulfing Austria, he supported Dollfuss's coup d'état, which established the Austrian fascist regime.[4] This support estranged Kraus from some of his followers.

In 1933 Kraus wrote Die Dritte Walpurgisnacht (The Third

Kraus never married, but from 1913 until his death he had a conflict-prone but close relationship with the Baroness

In 1911 Kraus was

Kraus was the subject of two books by Thomas Szasz, Karl Kraus and the Soul Doctors and Anti-Freud: Karl Kraus's Criticism of Psychoanalysis and Psychiatry, which portray Kraus as a harsh critic of Sigmund Freud and of psychoanalysis in general.[15] Other commentators, such as Edward Timms, have argued that Kraus respected Freud, though with reservations about the application of some of his theories, and that his views were far less black-and-white than Szasz suggests.[16]

Character

Karl Kraus was a subject of controversy throughout his lifetime. Marcel Reich-Ranicki called him 'vain, self-righteous and self-important'.[17] Kraus's followers saw in him an infallible authority who would do anything to help those he supported. Kraus considered posterity his ultimate audience, and reprinted Die Fackel in volume form years after it was first published.[18]

A concern with language was central to Kraus's outlook, and he viewed his contemporaries' careless use of language as symptomatic of their insouciant treatment of the world. Viennese composer Ernst Krenek described meeting the writer in 1932: "At a time when people were generally decrying the Japanese bombardment of Shanghai, I met Karl Kraus struggling over one of his famous comma problems. He said something like: 'I know that everything is futile when the house is burning. But I have to do this, as long as it is at all possible; for if those who were supposed to look after commas had always made sure they were in the right place, Shanghai would not be burning'."[19]

The Austrian author Stefan Zweig once called Kraus "the master of venomous ridicule" (der Meister des giftigen Spotts).[20] Up to 1930, Kraus directed his satirical writings to figures of the center and the left of the political spectrum, as he considered the flaws of the right too self-evident to be worthy of his comment.[18] Later, his responses to the Nazis included The Third Walpurgis Night.

To the numerous enemies he made with the inflexibility and intensity of his partisanship, however, he was a bitter

Giorgio Agamben compared Guy Debord and Kraus for their criticism of journalists and media culture.[22]

Gregor von Rezzori wrote of Kraus, "[His] life stands as an example of moral uprightness and courage which should be put before anyone who writes, in no matter what language... I had the privilege of listening to his conversation and watching his face, lit up by the pale fire of his fanatic love for the miracle of the German language and by his holy hatred for those who used it badly."[23]

Kraus's work has been described as the culmination of a literary outlook. Critic Frank Field quoted the words Bertolt Brecht wrote of Kraus, on hearing of his death: "As the epoch raised its hand to end its own life, he was the hand."[24]

Selected works

- Die demolierte Literatur [Demolished Literature] (1897)

- Eine Krone für Zion[A Crown for Zion] (1898)

- Sittlichkeit und Kriminalität [Morality and Criminal Justice] (1908)

- Sprüche und Widersprüche [Sayings and Contradictions] (1909)

- Die chinesische Mauer [The Wall of China] (1910)

- Pro domo et mundo [For Home and for the World] (1912)

- Nestroy und die Nachwelt [Nestroy and Posterity] (1913)

- Worte in Versen (1916–30)

- Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind) (1918)

- Weltgericht [The Last Judgment] (1919)

- Nachts [At Night] (1919)

- Untergang der Welt durch schwarze Magie [The End of the World Through Black Magic] (1922)

- Literatur (Literature) (1921)

- Traumstück [Dream Piece] (1922)

- Die letzten Tage der Menschheit: Tragödie in fünf Akten mit Vorspiel und Epilog [The Last Days of Mankind: Tragedy in Five Acts with Preamble and Epilogue] (1922)

- Wolkenkuckucksheim [Cloud Cuckoo Land] (1923)

- Traumtheater [Dream Theatre] (1924)

- Epigramme [Epigrams] (1927)

- Die Unüberwindlichen [The Insurmountables] (1928)

- Literatur und Lüge [Literature and Lies] (1929)

- Shakespeares Sonette (1933)

- Die Sprache [Language] (posthumous, 1937)

- Die dritte Walpurgisnacht [The Third Walpurgis Night] (posthumous, 1952)

Some works have been re-issued in recent years:

- Die letzten Tage der Menschheit, Bühnenfassung des Autors, 1992 Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-22091-8

- Die Sprache, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37817-1

- Die chinesische Mauer, mit acht Illustrationen von Oskar Kokoschka, 1999, Insel, ISBN 3-458-19199-2

- Aphorismen. Sprüche und Widersprüche. Pro domo et mundo. Nachts, 1986, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37818-X

- Sittlichkeit und Krimininalität, 1987, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37811-2

- Dramen. Literatur, Traumstück, Die unüberwindlichen u.a., 1989, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37821-X

- Literatur und Lüge, 1999, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37813-9

- Shakespeares Sonette, Nachdichtung, 1977, Diogenes, ISBN 3-257-20381-0

- Theater der Dichtung mit Bearbeitungen von Shakespeare-Dramen, Suhrkamp 1994, ISBN 3-518-37825-2

- Hüben und Drüben, 1993, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37828-7

- Die Stunde des Gerichts, 1992, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37827-9

- Untergang der Welt durch schwarze Magie, 1989, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37814-7

- Brot und Lüge, 1991, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37826-0

- Die Katastrophe der Phrasen, 1994, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37829-5

Works in English translation

- The Last Days of Mankind: A Tragedy in Five Acts (abridged). Translated by Gode, Alexander; Allen Wright, Sue. New York: F. Ungar Pub. Co. 1974. ISBN 9780804424844.

- No Compromise: Selected Writings of Karl Kraus (1977, ed. Frederick Ungar, includes poetry, prose, and aphorisms from Die Fackel as well as correspondences and excerpts from The Last Days of Mankind.)

- In These Great Times: A Karl Kraus Reader (1984), ed. Harry Zohn, contains translated excerpts from Die Fackel, including poems with the original German text alongside, and a drastically abridged translation of The Last Days of Mankind.

- Anti-Freud: Karl Kraus' Criticism of Psychoanalysis and Psychiatry (1990) by Thomas Szasz contains Szasz's translations of several of Kraus' articles and aphorisms on psychiatry and psychoanalysis.

- Half Truths and One-and-a-Half Truths: selected aphorisms (1990) translated by Hary Zohn. Chicago ISBN 0-226-45268-9.

- Dicta and Contradicta, tr. Jonathan McVity (2001), a collection of aphorisms.

- The Last Days of Mankind (1999) a radio drama broadcast on BBC Three. Paul Scofield plays The Voice of God. Adapted and directed by Giles Havergal. The 3 episodes were broadcast from 6 to 13 December 1999.

- Work in progress. An incomplete and extensively annotated English translation by Michael Russell of The Last Days of Mankind is available at http://www.thelastdaysofmankind.org. It consists currently of Prologue, Act I, Act II and the Epilogue, slightly more than 50 percent of the original text. This is part of a project to translate a complete performable text with a focus on performable English that in some (modest) ways reflects Kraus's prose and verse in German, with an apparatus of footnotes explaining and illustrating Kraus's complex and dense references. The all-verse Epilogue is now published as a separate text, available from Amazon as a book and on Kindle. Also on this site will be a complete "working'" translation by Cordelia von Klot, provided as a tool for students and the only version of the whole play accessible online, translated into English with the useful perspective of a German speaker.

- The Kraus Project: Essays by Karl Kraus (2013) translated by Jonathan Franzen, with commentary and additional footnotes by Paul Reitter and Daniel Kehlmann.

- In These Great Times and Other Writings (2014, translated with notes by Patrick Healy, ebook only from November Editions. Collection of eleven essays, aphorisms, and the prologue and first act of The Last Days of Mankind)

- www.abitofpitch.com is dedicated to publishing selected writings of Karl Kraus in English translation with new translations appearing in irregular intervals.

- The Last Days of Mankind (2015), complete text translated by Fred Bridgham and Edward Timms. Yale University Press.

- The Last Days of Mankind (2016), alternate translation by Patrick Healy, November Editions

- Third Walpurgis Night: the Complete Text (2020), translated by Fred Bridgham. Yale University Press.

References

Citations

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ "Nomination Database". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ quoted following Sprüche und Widersprüche (Sayings and Gainsayings), Suhrkamp, Frankfurt/M. 1984, p. 42

- ^ a b c d e Siegfried Mattl (2009) "The Ambivalence of Modernism From the Weimar Republic to National Socialism and Red Vienna", Modern Intellectual History, Volume 6, Issue 01, April 2009, pp. 223–234

- ^ a b c Sascha Bru, Gunther Martens (2006) The invention of politics in the European avant-garde (1906–1940) pp. 52–5

- ^ Carl R. Mueller, Introduction to Frank Wedekind: Four Major Plays, Vol 1, Lyme, NH: Smith and Krauss, 2000

- ^ Willett (1959), p. 73n.

- ^ Die Fackel, No. 404, December 1914, p. 1

- ^ Timms 1986, pp. 374, 380.

- ^ Kraus (1934) Die Fackel Nr. 890, "Warum die Fackel nicht erscheint", p. 26, quotation: "Gewalt kein Objekt der Polemik"

- ^ Kovacsics, Adan (2011) Seleción de artículos de «Die Fackel», p. 524, quotation: "la obra que Kraus escribió en 1933, pero que no publicó, en parte, como él mismo señala, porque no puede ser «la violencia objeto de polémica ni la locura objeto de sátira», en parte porque temía comprometer a sus amigos y seguidores en Alemania y ponerlos en peligro."

- ^ Freschi, Marino (1996) Preface to the Italian translation of The Third Walpurgis Night, pp. XXI–XXII , quotation: "Il progetto venne bloccato dalle remore avvertite da Kraus, preoccupato di coinvolgere amici e conoscenti citati nel libro e ostili a Hitler, che ancora vivevano nel Terzo Reich."

- ^ "The Question of Karl Kraus" (from The Revolt of the Pendulum, 2009), Australian Literary Review, March 2007, via clivejames.com

- ^ Timms 2005, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Szasz, Karl Kraus and the Soul-Doctors, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1977, pp. 19–20

- ^ Timms 1986, chpt. 5, "Sorcerers and Apprentices: The Encounter with Freud", especially pp. 107, 111–112.

- ^ Harry Zohn, Karl Kraus and the Critics, Camden House, 1997, p. 90

- ^ a b Knight, Charles A. (2004) Literature of Satire pp. 252–6

- ^ Hans Weigel, Kraus: Die Macht der Ohnmacht (Kraus or the power of powerlessness), Brandstätter, 1986, p. 128. Original text: "Als man sich gerade über die Beschießung von Shanghai durch die Japaner erregte und ich Karl Kraus bei einem der berühmten Beistrich-Problemen antraf, sagte er ungefähr: Ich weiß, daß das alles sinnlos ist, wenn das Haus in Brand steht. Aber solange das irgend möglich ist, muß ich das machen, denn hätten die Leute, die dazu verpflichtet sind, immer darauf geachtet, daß die Beistriche am richtigen Platz stehen, so würde Shanghai nicht brennen.“

- ^ Stefan Zweig, Die Welt von Gestern. Erinnerungen eines Europäers (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 1986), 127.

- ^ Marmo, Emanuela (March 2004). "Interview with Daniele Luttazzi". Archived from the original on 6 May 2006. Retrieved 6 May 2006.

Quando la satira poi riesce a far ridere su un argomento talmente drammatico di cui si ride perché non c'è altra soluzione possibile, si ha quella che nei cabaret di Berlino degli Anni '20 veniva chiamata la 'risata verde'. È opportuno distinguere una satira ironica, che lavora per sottrazione, da una satira grottesca, che lavora per addizione. Questo secondo tipo di satira genera più spesso la risata verde. Ne erano maestri Kraus e Valentin.

- ^ Giorgio Agamben in Debord Commentari sulla società dello spettacolo, quotation: "Se c'è, nel nostro secolo, uno scrittore con cui Debord accetterebvbe forse di essere paragonato, questi è Karl Kraus. Nessuno ha saputo, come Kraus nella sua caparbia lotta coi giornalisti, portare alla luce le leggi nascoste dello spettacolo, «i fatti che producono notizie e le notizie che sono colpevoli dei fatti». E se si dovesse immaginare qualcosa che corrisponde alla voce fuori campo che nei film di Debord accompagna l'esposizione del deserto di macerie dello spettacolo, nulla di più appropriato che la voce di Kraus (...) È nota la battuta con cui, nella postuma Terza notte di Valpurga, Kraus giustifica il suo silenzio davanti all'avvento del nazismo: «Su Hitler non mi viene in mente nulla»."

- ^ Gregor von Rezzori (1979) Memoirs of an Anti-Semite. Middlesex; Penguin; pp. 219–220.

- ^ Frank Field, The Last Days of Mankind: Karl Kraus and his Vienna, Macmillan, 1967, p. 242

Sources

- Karl Kraus by L. Liegler (1921)

- Karl Kraus by W. Benjamin (1931)

- Karl Kraus by R. von Schaukal (1933)

- Karl Kraus in Sebstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten by P. Schick (1965)

- The Last Days of Mankind: Karl Kraus and His Vienna by Frank Field (1967)

- Karl Kraus by W.A. Iggers (1967)

- Karl Kraus by H. Zohn (1971)

- Wittgenstein's Vienna by A. Janik and S. Toulmin (1973)

- Karl Kraus and the Soul Doctors by T.S. Szasz (1976)

- Masks of the Prophet: The Theatrical World of Karl Kraus by Kari Grimstad (1981)

- McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of World Drama, vol. 3, ed. by Stanley Hochman (1984)

- ISBN 0-300-10751-X.

- Anti-Freud: Karl Kraus's Criticism of Psychoanalysis and Psychiatry by Thomas Szasz (1990)

- The Paper Ghetto: Karl Kraus and Anti-Semitism by John Theobald (1996)

- Karl Kraus and the Critics by Harry Zohn (1997)

- Otto Weininger: Sex, Science, and Self in Imperial Vienna by Chandak Sengoopta pp. 6, 23, 35–36, 39–41, 43–44, 137, 141–45

- Linden, Ari. "Beyond Repetition: Karl Kraus's 'Absolute Satire'." German Studies Review 36.3 (2013): 515–536.

- Linden, Ari. "Quoting The Language Of Nature In Karl Kraus's Satires." Journal of Austrian Studies 46.1 (2013): 1–22.

- Bloch, Albert (1937). "Karl Kraus' Shakespeare". Books Abroad. 11 (1): 21–24. JSTOR 40077864.

- Willett, John (1959). The Theatre of Bertolt Brecht: A Study from Eight Aspects. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-34360-X.

External links

- The Life and Work of Karl Kraus

- Truth and Beauty- a successor publication by his great-nephew, Eric Kraus

- On Jonathan Franzen's Karl Kraus by Joshua Cohen, at The London Review of Books

- Digitalized edition of Die Fackel (registration required) from the Austrian Academy of Science AAC (user interface in German and English)

- Karl Kraus – Weltgericht (The Last Judgement). Polemiken gegen den Krieg (Polemics against the War) – Online-Exhibition in German, including original film footage (2014)

- Works by or about Karl Kraus at Internet Archive

- Works by Karl Kraus at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)