Kawasaki disease

| Kawasaki disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Kawasaki syndrome, immunoglobulin[1] |

| Prognosis | Mortality 0.2% with treatment[4] |

| Frequency | 8–124 per 100,000 people under five[5] |

| Named after | Tomisaku Kawasaki |

Kawasaki disease (also known as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome) is a

While the specific cause is unknown, it is thought to result from an excessive

Typically, initial treatment of Kawasaki disease consists of high doses of

Kawasaki disease is rare.[1] It affects between 8 and 67 per 100,000 people under the age of five except in Japan, where it affects 124 per 100,000.[5] Boys are more commonly affected than girls.[1] The disorder is named after Japanese pediatrician Tomisaku Kawasaki, who first described it in 1967.[5][14]

Signs and symptoms

Kawasaki disease often begins with a high and persistent fever that is not very responsive to normal treatment with paracetamol (acetaminophen) or ibuprofen.[15][16] This is the most prominent symptom of Kawasaki disease, and is a characteristic sign that the disease is in its acute phase; the fever normally presents as a high (above 39–40 °C) and remittent, and is followed by extreme irritability.[16][17] Recently, it is reported to be present in patients with atypical or incomplete Kawasaki disease;[18][19] nevertheless, it is not present in 100% of cases.[20]

The first day of fever is considered the first day of the illness,

Bilateral

Kawasaki disease also presents with a set of mouth symptoms, the most characteristic of which are a red tongue, swollen lips with vertical cracking, and bleeding.

| Less common manifestations | |

|---|---|

| System | Manifestations |

GIT

|

|

MSS

|

Polyarthritis and arthralgia |

| CVS | Myocarditis, pericarditis, tachycardia,[31] valvular heart disease |

| GU | |

| CNS | sensorineural deafness

|

| RS | Shortness of breath,[31] influenza-like illness, pleural effusion, atelectasis |

| Skin | BCG vaccination site, Beau's lines, and finger gangrene

|

| Source: review,[31] table.[35] | |

In the acute phase of the disease, changes in the

The most common skin manifestation is a diffuse

In the acute stage of Kawasaki disease, systemic inflammatory changes are evident in many organs.

Other reported

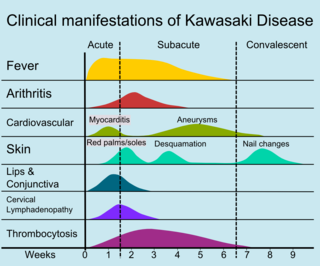

The course of the disease can be divided into three clinical phases.[47]

- The aneurysms are generally not yet visible by echocardiography.

- The

- The convalescent stage begins when all clinical signs of illness have disappeared, and continues until the sedimentation rate returns to normal, usually at six to eight weeks after the onset of illness.[31]

Adult onset of Kawasaki disease is rare.

Some children, especially young

Cardiac

Heart complications are the most important aspect of Kawasaki disease, which is the leading cause of heart disease acquired in childhood in the United States and Japan.

Even when treated with high-dose

Many risk factors predicting coronary artery aneurysms have been identified, Coronary artery lesions resulting from Kawasaki disease change dynamically with time.

MI caused by thrombotic occlusion in an aneurysmal, stenotic, or both aneurysmal and stenotic coronary artery is the main cause of death from Kawasaki disease.[61] The highest risk of MI occurs in the first year after the onset of the disease.[61] MI in children presents with different symptoms from those in adults. The main symptoms were shock, unrest, vomiting, and abdominal pain; chest pain was most common in older children.[61] Most of these children had the attack occurring during sleep or at rest, and around one-third of attacks were asymptomatic.[15]

Other

Other Kawasaki disease complications have been described, such as aneurysm of other arteries:

Gastrointestinal complications in Kawasaki disease are similar to those observed in

The neurological complications per central nervous system lesions are increasingly reported.

Causes

The specific cause of Kawasaki disease is unknown.

Circumstantial evidence points to an infectious cause.

Seasonal trends in the appearance of new cases of Kawasaki disease have been linked to tropospheric wind patterns, which suggests wind-borne transport of something capable of triggering an immunologic cascade when inhaled by genetically susceptible children.[6] Winds blowing from central Asia correlate with numbers of new cases of Kawasaki disease in Japan, Hawaii, and San Diego.[109] These associations are themselves modulated by seasonal and interannual events in the El Niño–Southern Oscillation in winds and sea surface temperatures over the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean.[110] Efforts have been made to identify a possible pathogen in air-filters flown at altitude above Japan.[111] One source has been suggested in northeastern China.[6][112]

Genetics

Genetic susceptibility is suggested by increased incidence among children of Japanese descent around the world, and also among close and extended family members of affected people.

SNPs in

Diagnosis

| Criteria for diagnosis |

|---|

| Fever of ≥5 days' duration associated with at least four† of these five changes |

| Bilateral nonsuppurative conjunctivitis |

| One or more changes of the mucous membranes of the "strawberry" tongue

|

| One or more changes of the arms and legs, including redness, swelling, skin peeling around the nails, and generalized peeling |

| Polymorphous rash, primarily truncal |

| Large lymph nodes in the neck (>15 mm in size) |

| Disease cannot be explained by some other known disease process |

| †A diagnosis of Kawasaki disease can be made if fever and only three changes are present if coronary artery disease is documented by two-dimensional coronary angiography .

|

| Source: Nelson's essentials of pediatrics,[117] Review[118] |

Since no specific laboratory test exists for Kawasaki disease, diagnosis must be based on clinical

Classically, five days of fever[121] plus four of five diagnostic criteria must be met to establish the diagnosis. The criteria are:[122]

- erythema of the lips or oral cavity or cracking of the lips

- rash on the trunk

- swelling or erythema of the hands or feet

- red eyes (conjunctival injection)

- swollen lymph node in the neck of at least 15 mm

Many children, especially infants, eventually diagnosed with Kawasaki disease, do not exhibit all of the above criteria. In fact, many experts now recommend treating for Kawasaki disease even if only three days of fever have passed and at least three diagnostic criteria are present, especially if other tests reveal abnormalities consistent with Kawasaki disease. In addition, the diagnosis can be made purely by the detection of coronary artery aneurysms in the proper clinical setting.[citation needed]

Investigations

A physical examination will demonstrate many of the features listed above.

Blood tests

- thrombocytosis.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate will be elevated.

- C-reactive protein will be elevated.

- Liver function tests may show evidence of hepatic inflammation and low serum albumin levels.[123]

Other optional tests include:

- arrhythmiadue to myocarditis.

- Echocardiogram may show subtle coronary artery changes or, later, true aneurysms.

- computerized tomography may show hydrops (enlargement) of the gallbladder.

- Urinalysis may show white blood cells and protein in the urine (pyuria and proteinuria) without evidence of bacterial growth.

- Lumbar puncture may show evidence of aseptic meningitis.

- Angiography was historically used to detect coronary artery aneurysms, and remains the gold standard for their detection, but is rarely used today unless coronary artery aneurysms have already been detected by echocardiography.

Biopsy is rarely performed, as it is not necessary for diagnosis.[8]

Subtypes

Based on clinical findings, a diagnostic distinction may be made between the 'classic' / 'typical' presentation of Kawasaki disease and 'incomplete' / 'atypical' presentation of a "suspected" form of the disease.[6] Regarding 'incomplete' / 'atypical' presentation, American Heart Association guidelines state that Kawasaki disease "should be considered in the differential diagnosis of prolonged unexplained fever in childhood associated with any of the principal clinical features of the disease, and the diagnosis can be considered confirmed when coronary artery aneurysms are identified in such patients by echocardiography."[6]

A further distinction between 'incomplete' and 'atypical' subtypes may also be made in the presence of non-typical symptoms.[47]

Case definition

For study purposes, including

Differential diagnosis

The broadness of the differential diagnosis is a challenge to timely diagnosis of Kawasaki disease.

Kawasaki-like disease temporally associated with COVID-19

In 2020, reports of

Several reported cases suggest that this Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory syndrome is not limited to children; there is the possibility of an analogous disease in adults, which has been termed MIS-A. Some suspected patients have presented with positive test results for SARS-CoV-2 and reports suggest intravenous immunoglobulin, anticoagulation, tocilizumab, plasmapheresis and steroids are potential treatments.[128][129][130]

Classification

Debate has occurred about whether Kawasaki disease should be viewed as a characteristic immune response to some infectious

Inflammation, or

Other diseases involving necrotizing vasculitis include polyarteritis nodosa, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis.[132]

Kawasaki disease may be further classified as a medium-sized vessel vasculitis, affecting medium- and small-sized blood vessels,

It can also be classed as an autoimmune form of vasculitis.[4] It is not associated with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, unlike other vasculitic disorders associated with them (such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis).[132][138] This form of categorization is relevant for appropriate treatment.[139]

Treatment

Children with Kawasaki disease should be hospitalized and cared for by a physician who has experience with this disease. In an academic medical center, care is often shared between pediatric

High-dose aspirin is associated with anemia and does not confer benefit to disease outcomes.[146]

About 15-20% of children following the initial IVIG infusion show persistent or recurrent fever and are classified as IVIG-resistant. While the use of

Prognosis

With early treatment, rapid recovery from the acute symptoms can be expected, and the risk of coronary artery aneurysms is greatly reduced. Untreated, the acute symptoms of Kawasaki disease are self-limited (i.e. the patient will recover eventually), but the risk of coronary artery involvement is much greater, even many years later. Many cases of myocardial infarction in young adults have now been attributed to Kawasaki disease that went undiagnosed during childhood.[6] Overall, about 2% of patients die from complications of coronary vasculitis.[citation needed]

Laboratory evidence of increased inflammation combined with demographic features (male sex, age less than six months or greater than eight years) and incomplete response to IVIG therapy create a profile of a high-risk patient with Kawasaki disease.

A

Rarely, recurrence can occur in Kawasaki disease with or without treatment.[160][161]

Epidemiology

Kawasaki disease affects boys more than girls, with people of Asian ethnicity, particularly Japanese people. The higher incidence in Asian populations is thought to be linked to

Currently, Kawasaki disease is the most commonly diagnosed pediatric vasculitis in the world. By far, the highest incidence of Kawasaki disease occurs in Japan, with the most recent study placing the attack rate at 218.6 per 100,000 children less than five years of age (about one in 450 children). At this present attack rate, more than one in 150 children in Japan will develop Kawasaki disease during their lifetimes.[citation needed]

However, its incidence in the United States is increasing. Kawasaki disease is predominantly a disease of young children, with 80% of patients younger than five years of age. About 2,000–4,000 cases are identified in the U.S. each year (9 to 19 per 100,000 children younger than five years of age).[140][163][164] In the continental United States, Kawasaki disease is more common during the winter and early spring, boys with the disease outnumber girls by ≈1.5–1.7:1, and 76% of affected children are less than 5 years of age.[165]

In the United Kingdom, prior to 2000, it was diagnosed in fewer than one in every 25,000 people per year.[166] Incidence of the disease doubled from 1991 to 2000, however, with four cases per 100,000 children in 1991 compared with a rise of eight cases per 100,000 in 2000.[167] By 2017, this figure had risen to 12 in 100,000 people with 419 diagnosed cases of Kawasaki disease in the United Kingdom.[168]

In Japan, the rate is 240 in every 100,000 people.[169]

Coronary artery aneurysms due to Kawasaki disease are believed to account for 5% of acute coronary syndrome cases in adults under 40 years of age.[6]

History

The disease was first reported by Tomisaku Kawasaki in a four-year-old child with a rash and fever at the Red Cross Hospital in Tokyo in January 1961, and he later published a report on 50 similar cases.[14] Later, Kawasaki and colleagues were persuaded of definite cardiac involvement when they studied and reported 23 cases, of which 11 (48%) patients had abnormalities detected by an electrocardiogram.[170] In 1974, the first description of this disorder was published in the English-language literature.[171] In 1976, Melish et al. described the same illness in 16 children in Hawaii.[172] Melish and Kawasaki had independently developed the same diagnostic criteria for the disorder, which are still used today to make the diagnosis of classic Kawasaki disease. Dr. Kawasaki died on June 5, 2020, at the age of 95.[173]

A question was raised whether the disease only started during the period between 1960 and 1970, but later a preserved heart of a seven-year-old boy who died in 1870 was examined and showed three aneurysms of the coronary arteries with clots, as well as pathologic changes consistent with Kawasaki disease.[174] Kawasaki disease is now recognized worldwide. Why cases began to emerge across all continents around the 1960s and 1970s is unclear.[175] Possible explanations could include confusion with other diseases such as scarlet fever, and easier recognition stemming from modern healthcare factors such as the widespread use of antibiotics.[175] In particular, old pathological descriptions from Western countries of infantile polyarteritis nodosa coincide with reports of fatal cases of Kawasaki disease.[6]

In the United States and other developed nations, Kawasaki disease appears to have replaced acute rheumatic fever as the most common cause of acquired heart disease in children.[176]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Kawasaki Disease". PubMed Health. NHLBI Health Topics. 11 June 2014. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ^ a b c Guidance – Paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 (PDF), The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2020

- ^ PMID 17191303.

- ^ ISBN 9781118742488. Archivedfrom the original on 11 September 2017.

- ^ PMID 31356128.

- ^ Owens, AM (2023). Kawasaki Disease. StatPearls Publishing.

- ^ PMID 30725848. Archived from the originalon 6 May 2020.

- ^ S2CID 54477877.

- ^ PMID 32499548.

- PMID 32768466.

- ^ a b "Merck Manual, Online edition: Kawasaki Disease". 2014. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- PMID 31843876.

- ^ PMID 6062087.

- ^ PMID 9665974.

- ^ PMID 7760506.

- ISBN 0721652441.

- S2CID 40359434.

- PMID 3819942.

- S2CID 1471650.

- ^ PMID 10931408.

- PMID 1709446.

- ^ PMID 21860641.

- PMID 14519302.

- PMID 18401983.

- S2CID 40875550.

- PMID 10653425.

- PMID 2468129.

- ^ S2CID 32280647.

- ^ PMID 18059239.

- ^ PMID 19851663.

- S2CID 32616639.

- PMID 3316594.

- PMID 19997548.

- PMID 19851663.

- PMID 19483521.

- PMID 10999876.

- ^ PMID 18053534.

- PMID 10083641.

- S2CID 22194695.

- PMID 18043462.

- PMID 8491037.

- ^ S2CID 12989507.

- PMID 20359606.

- PMID 12006960.

- ^ "Clinical manifestations of Kawasaki disease". Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2011.[non-primary source needed][full citation needed]

- ^ PMID 30157897.

- ^ PMID 7264399.

- ^ PMID 17443379.

- PMID 3772656.

- S2CID 6125622.

- S2CID 20301847.

- S2CID 22210926. Archived from the originalon 2 May 2020.

- PMID 9427895.

- PMID 8313588.

- PMID 18260333.

- S2CID 56991692.

- ^ PMID 3950818.

- ^ PMID 8822996.

- ^ PMID 3802442.

- ^ PMID 3712157.

- PMID 3341217.

- PMID 2382613.

- PMID 3958349.

- PMID 8665019.

- PMID 11274955.

- S2CID 30968335.

- S2CID 30747089.

- ^ PMID 21691693.

- S2CID 11627024.

- ^ PMID 8901658.

- PMID 16820386.

- S2CID 21586626.

- ^ PMID 14715193.

- due to ethical violations.

- PMID 16150324.

- PMID 18756065.

- PMID 11283899.

- PMID 15121996.

- PMID 12838207.

- PMID 7201245.

- PMID 7299613.

- PMID 15206604.

- PMID 17913174.

- PMID 1571415.

- PMID 11587880.

- PMID 2223179.

- PMID 3344468.

- PMID 11589317.

- ^ PMID 9660380.

- ^ PMID 1622525.

- S2CID 19461613.

- S2CID 207161115.

- PMID 11562886.

- PMID 14647816.

- PMID 15916701.

- PMID 10807296.

- PMID 18364728.

- ^ "Kawasaki Disease". American Heart Association. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ "Kawasaki Disease: Causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ PMID 30619331.

- PMID 30619784.

- ^ PMID 32173601.

- PMID 19075496.

- PMID 29105346.

- S2CID 24155085.

- PMID 32546853.

- S2CID 211034768.

- PMID 22355668.

- .

- PMID 22481336.

- PMID 24843117.

- ^ PMID 28656474.

- ^ PMC 7161397.

- ^ PMID 32095191.

- PMID 27506874.

- ISBN 1-4160-0159-X.

- ^ PMID 16322081.

- PMID 27056781.

- mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- from the original on 17 May 2008.

- ^ "Kawasaki Disease Diagnostic Criteria". Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- S2CID 13412642.

- PMID 27863715.

- PMID 34716418.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b "Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents with COVID-19". www.who.int. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) Associated with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". emergency.cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 May 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- PMID 35031265.

- PMID 33031361.

- PMID 32659211.

- PMID 32511667.

- ^ PMID 18524103.

- ^ "necrotizing vasculitis – definition of necrotizing vasculitis". Free Online Medical Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- PMID 19946711.

- S2CID 15223179.

- PMID 19377760.

- PMID 18761873.

- PMID 17408915.

- S2CID 25260955.

- ^ Children's Hospital Boston. Archived from the originalon 23 November 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ PMID 14584002.

- PMID 37092277.

- PMID 15545617.

- PMID 17054199.

- ^ "Kawasaki Disease Treatment & Management". Medscape – EMedicine. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- PMID 26658843.

- PMID 31425625.

- S2CID 72335365.

- PMID 12838187.

- PMID 17301297.

- PMID 35622534.

- PMID 9605052.

- PMID 3423060.

- PMID 4061324.

- PMID 3668739.

- S2CID 39330448.

- PMID 10931409.

- S2CID 29371025. Archived from the original(PDF) on 9 August 2017.

- PMID 9310527.

- S2CID 186231502.

- ISBN 9780323296991.

- S2CID 37677965.

- ^ "Kawasaki Disease". ucsfbenioffchildrens.org.

- ^ "Kawasaki Syndrome". CDC. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- PMID 12949272.

- ^ "BBC Health: Kawasaki Disease". 31 March 2009. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011.

- ^ "Rare heart disease rate doubles". BBC. 17 June 2002. Archived from the original on 26 May 2004.

- .

- ^ "Kawasaki disease in kids at record high". The Japan Times. 17 March 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Yamamoto T, Oya T, Watanabe A (1968). "Clinical features of Kawasaki disease". Shonika Rinsho (in Japanese). 21: 291–97.

- S2CID 13221240.

- PMID 7134.

- ^ "Pediatrician who discovered Kawasaki disease dies at 95". Kyodo News+. 10 June 2020. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020.

- ^ Gee SJ (1871). "Cases of morbid anatomy: aneurysms of coronary arteries in a boy". St Bartholomew's Hosp Rep. 7: 141–8, See p. 148.

- ^ S2CID 34446653.

- ISSN 0531-5131.

External links

- Kawasaki disease at Curlie