Kenorland

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2016) |

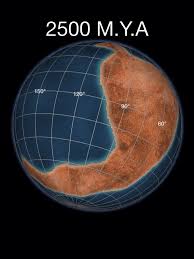

Map of Kenorland supercontinent 2.5 billion years ago[citation needed] | |

| Historical continent | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 2.72 Ga |

| Type | Supercontinent |

| Today part of | Era c. 2.72 billion years ago (2.72 Ga) by the accretion of Neoarchaean cratons and the formation of new continental crust. It comprised what later became Laurentia (the core of today's North America and Greenland), Baltica (today's Scandinavia and Baltic), Western Australia and Kalaharia.[1]

Swarms of volcanic paleomagnetic orientation as well as the existence of similar stratigraphic sequences permit this reconstruction. The core of Kenorland, the Baltic/Fennoscandian Shield, traces its origins back to over 3.1 Ga. The Yilgarn Craton (present-day Western Australia) contains zircon crystals in its crust that date back to 4.4 Ga.

Kenorland was named after the Kenoran orogeny (also called the Algoman orogeny),[2] which in turn was named after the town of Kenora, Ontario.[3] FormationKenorland was formed around 2.72 billion years ago (2.72 Ga) as a result of a series of accretion events and the formation of new continental crust.[4] The accretion events are recorded in the greenstone belts of the Yilgarn Craton as metamorphosed basalt belts and granitic domes accreted around the high grade metamorphic core of the Western Gneiss Terrane, which includes elements of up to 3.2 Ga in age and some older portions, for example the Narryer Gneiss Terrane. Breakup or disassemblyPaleomagnetic studies show Kenorland was in generally low sedimentary rift-basins and rift-margins on many continents.[1] On early Earth, this type of bimodal deep mantle plume rifting was common in Archaean and Neoarchaean crust and continent formation.

The geological time period surrounding the breakup of Kenorland is thought by many geologists to be the beginning of the transition point from the deep-mantle-plume method of continent formation in the core) to the subsequent two-layer core-mantle plate tectonics convection theory. However, the findings of an earlier continent, Ur, and a supercontinent of around 3.1 Gya, Vaalbara , indicate this transition period may have occurred much earlier.

The Kola and Karelia cratons began to drift apart around 2.45 Gya, and by 2.4 Gya the Kola craton was at about 30 degrees south latitude and the Karelia craton was at about 15 degrees south latitude. Paleomagnetic evidence shows that at 2.45 Gya the Yilgarn craton (now the bulk of Western Australia) was not connected to Fennoscandia-Laurentia and was at about ~5 degrees south latitude.[citation needed ]

This implies that at 2.515 Gya an ocean existed between the Kola and Karelia cratons, and that by 2.45 Gya there was no longer a supercontinent. Also, there is speculation based on the rift margin spatial arrangements of Laurentia, that at some time during the breakup, the Neoarchaean landmasses (supercratons) on opposite ends of a very large Kenorland. This is based on how drifting assemblies of various constituent pieces should flow reasonably together toward the amalgamation of the new subsequent continent. The Slave and Superior cratons now constitute the northwest and southeast portions of the Canadian Shield , respectively.

The breakup of Kenorland was contemporary with the glaciation which persisted for up to 60 million years. The banded iron formations (BIF) show their greatest extent at this period, thus indicating a massive increase in oxygen build-up from an estimated 0.1% of the atmosphere to 1%. The rise in oxygen levels caused the virtual disappearance of the greenhouse gas methane (oxidized into carbon dioxide and water).

The simultaneous breakup of Kenorland generally increased continental rainfall everywhere, thus increasing erosion and further reducing the other greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide. With the reduction in greenhouse gases, and with solar output being less than 85% its current power, this led to a runaway Snowball Earth scenario, where average temperatures planet-wide plummeted to below freezing. Despite the anoxia indicated by the BIF, photosynthesis continued, stabilizing climates at new levels during the second part of the Proterozoic Era. References

Bibliography

|