Keratinocyte

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (November 2020) |

Keratinocytes are the primary type of

Function

The primary function of keratinocytes is the formation of a barrier against environmental damage by heat, UV radiation, dehydration, pathogenic bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses.

Pathogens invading the upper layers of the epidermis can cause keratinocytes to produce

Structure

A number of

Cell differentiation

Epidermal stem cells reside in the lower part of the epidermis (stratum basale) and are attached to the basement membrane through

During this differentiation process, keratinocytes permanently withdraw from the cell cycle, initiate expression of epidermal differentiation markers, and move suprabasally as they become part of the stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, and eventually corneocytes in the stratum corneum.

Corneocytes are keratinocytes that have completed their differentiation program and have lost their

At each stage of differentiation, keratinocytes express specific

In humans, it is estimated that keratinocytes

Factors promoting keratinocyte differentiation are:

- A

- genes involved in keratinocyte differentiation.[17][18] Keratinocytes are the only cells in the body with the entire vitamin D metabolic pathway from vitamin D production to catabolism and vitamin D receptor expression.[19]

- Cathepsin E.[20]

- TALE transcription factors.[21]

- Hydrocortisone.[22]

Since keratinocyte differentiation inhibits keratinocyte proliferation, factors that promote keratinocyte proliferation should be considered as preventing differentiation. These factors include:

- The transcription factor p63, which prevents epidermal stem cells from differentiating into keratinocytes.[23] Mutations in the p63 DNA-binding domain are associated with ectrodactyly, ectodermal dysplasia, and cleft lip/palate (EEC) syndrome. The transcriptome of p63 mutant keratinocytes deviated from the normal epidermal cell identity. [24]

- Vitamin A and its analogues.[25]

- Epidermal growth factor.[26]

- Transforming growth factor alpha.[27]

- Cholera toxin.[22]

Interaction with other cells

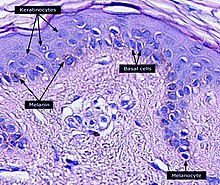

Within the epidermis keratinocytes are associated with other cell types such as

Keratinocytes contribute to protecting the body from

Role in wound healing

At the opposite, epidermal keratinocytes, can contribute to de novo hair follicle formation during the healing of large wounds.[31]

Functional keratinocytes are needed for tympanic perforation healing.[32]

Sunburn cells

A sunburn

Aging

With age, tissue homeostasis declines partly because stem/progenitor cells fail to self-renew or differentiate. DNA damage caused by exposure of stem/progenitor cells to reactive oxygen species (ROS) may play a key role in epidermal stem cell aging. Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) ordinarily protects against ROS. Loss of SOD2 in mouse epidermal cells was observed to cause cellular senescence that irreversibly arrested proliferation in a fraction of keratinocytes.[35] In older mice, SOD2 deficiency delayed wound closure and reduced epidermal thickness.[35]

Civatte body

A Civatte body (named after the French dermatologist Achille Civatte, 1877–1956)

See also

- Epidermis

- Skin

- Corneocyte

- Keratin

- HaCaT

- List of human cell types derived from the germ layers

- Epidermidibacterium keratini

- List of distinct cell types in the adult human body

References

- ISBN 978-0-632-06429-8. Archived from the originalon 2020-05-20. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6. Archived from the originalon 2010-10-11. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- ^ ISBN 978-0878932436.

Throughout life, the dead keratinized cells of the cornified layer are shed (humans lose about 1.5 grams of these cells each day*) and are replaced by new cells, the source of which is the mitotic cells of the Malpighian layer. Pigment cells (melanocytes) from the neural crest also reside in the Malpighian layer, where they transfer their pigment sacs (melanosomes) to the developing keratinocytes.

- ^ S2CID 25671082.

- ^ PMID 11250888.

- ^ PMID 19686098.

- ^ S2CID 30165907.

- )

- S2CID 22475141.

- S2CID 31353914.

- PMID 2702726.

- S2CID 21264605.

- S2CID 25858560.

- S2CID 8072916.

- S2CID 13063458.

- PMID 10469331.

- S2CID 23896865.

- PMID 7910167.

- PMID 9415400.

- S2CID 21148292.

- PMID 21511732.

- ^ S2CID 53294766.

- PMID 17114587.

- PMID 30566872.

- S2CID 23796587.

- S2CID 27427541.

- S2CID 21054962.

- ^

Brenner M; Hearing VJ. (May–June 2008). "The Protective Role of Melanin Against UV Damage in Human Skin". PMID 18435612.

- S2CID 52869761.

- PMID 16203973.

- S2CID 887738.

- ^ Y Shen, Y Guo, C Du, M Wilczynska, S Hellström, T Ny, Mice Deficient in Urokinase-Type Plasminogen Activator Have Delayed Healing of Tympanic Membrane Perforations, PLOS ONE, 2012

- ^

Young AR (June 1987). "The sunburn cell". PMID 3317295.

- ^

Sheehan JM, Young AR (June 2002). "The sunburn cell revisited: an update on mechanistic aspects". S2CID 21184034.

- ^ PMID 26240345.

- ISBN 1-84214-100-7.

- ^ PMID 23919028.

External links

- Tang L, Wu JJ, Ma Q, et al. (July 2010). "Human lactoferrin stimulates skin keratinocyte function and wound re-epithelialization". The British Journal of Dermatology. 163 (1): 38–47. S2CID 2387064.