Ketubah

A ketubah (

History

According to the

At any rate, the rabbis in ancient times insisted on the marriage couple entering into the ketubah as a protection for the wife. It acted as a replacement of the biblical mohar – the price paid by the groom to the bride, or her parents, for the marriage (i.e., the bride price).[7] The ketubah served as a contract, whereby the amount due to the wife (the bride-price) came to be paid in the event of the cessation of marriage, either by the death of the husband or divorce. The biblical mohar created a major social problem: many young prospective husbands could not raise the mohar at the time when they would normally be expected to marry. So, to enable these young men to marry, the rabbis, in effect, delayed the time that the amount would be payable, when they would be more likely to have the sum.[8] The mechanism adopted was to provide for the mohar to be a part of the ketubah. Both the mohar and the ketubah amounts served the same purpose: the protection for the wife should her support by her husband (either by death or divorce) cease. The only difference between the two systems was the timing of the payment. A modern secular equivalent would be the entitlement to alimony in the event of divorce.

The ketubah amount served as a disincentive for the husband contemplating

Monies pledged in a woman's ketubah can be written in local currencies, but must have the transactional market-value of the aforementioned weight in silver. Most ketubot also contain an additional liability, known as the "additional jointure" (Heb. תוספת = increment), whereby the groom pledges addition money to his bride. In Ashkenazi tradition, the custom is to consolidate these different financial obligations, or pledges, into one single, aggregate sum. In other Jewish communities, the custom was to write out all financial obligations as individual components.

Archaeological discoveries

The ketubah of Babatha, a 2nd-century woman who lived near the Dead Sea, was discovered in 1960 in the Cave of Letters.[12]

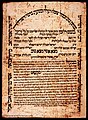

Over two hundred ketubot were discovered, among other manuscripts, in the Cairo Geniza.[13] They date between the 6th and 19th centuries and, whilst many consist of plain text, there are examples that use decorative devices such as micrography[14] and illumination[15] to elaborate them.

Composition

Content

The content of the ketubah is in essence a two-way contract that formalizes the various requirements by

As in most contracts made between two parties, there are mutual obligations, conditions and terms of reciprocity for such a contract to hold up as good. Thus said

Bat-Kohen variation

The

Design and language

The ketubah is a significant popular form of Jewish ceremonial art. Ketubot have been made in a wide range of designs, usually following the tastes and styles of the era and region in which they are made. Today, styles and decorations on ketubahs are chosen by the couple as a representation of their personal styles. This is contrasting to other Jewish legal or sacred texts (such as the Talmud, Mishnah, etc.), which cannot be decorated.

Traditional ketubot are not written in the

In recent years ketubot have become available in a variety of formats as well as the traditional Aramaic text used by the Orthodox community. Available texts include Conservative text, using the

Usage

Role in wedding ceremony

In a traditional Jewish wedding ceremony, the ketubah is signed by two witnesses and traditionally read out loud under the chuppah between the erusin and nissuin. Friends or distant relatives are invited to witness the ketubah, which is considered an honour; close relatives are prohibited from being witnesses. The witnesses must be halakhically valid witnesses, and so cannot be a blood relative of the couple. In Orthodox Judaism, women are also not considered to be valid witnesses. The ketubah is handed to the bride (or, more commonly, to the bride's mother) for safekeeping.

Display

Ketubot are often hung prominently in the home by the married couple as a daily reminder of their vows and responsibilities to each other.

However, in some communities, the ketubah is either displayed in a very[

Conditio sine qua non

According to Jewish law, spouses are prohibited from living together if the ketubah has been destroyed, lost, or is otherwise unretrievable.[25][26] In such case a second ketubah is made up (called a Ketubah De'irkesa), which states in its opening phrase that it comes to substitute a previous ketubah that has been lost.

Illuminated ketubot

-

Marriage contract from Venice, Italy, 1750

-

Yemenite Ketubah from 1794, now at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design

-

Marriage contract from Yemen, 1890

-

Marriage contract from Iraq

See also

References

- ISBN 0-550-10105-5.

- ^ Rabbi Victor S. Appell. "I recently became engaged and my fiancée said we need to get a ketubah. Can you explain what a ketubah is?".

- ^ "The Value and Significance of the Ketubah," Broyde, Michael and Jonathan Reiss. Journal of Halacha and Contemporary Society, XLVII, 2004.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 14b. Cf. Ketubbot 11a; 82b

- ^ Maimonides, Mishneh Torah (Hil. Ishuth 10:7). Cf. Babylonian Talmud, Ketubbot 10a, where R' Simeon ben Gamaliel II held the view that the ketubah was a teaching derived from the Law of Moses.

- OCLC 233044594., mitzvah # 552

- ^ Mentioned in Genesis 34:12, Exodus 22:16–17, Deuteronomy 20:7, Deuteronomy 22:29, Hosea 2:19–20

- ISBN 9783856168476.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - OCLC 60034030., Bekhorot 8:7, s.v. במנה צורי

- OCLC 31818927. (reprinted from Jerusalem editions, 1907, 1917 and 1988)

- OCLC 762505465. Based on the computation of Rabbi Shelomo Qorah, chief Rabbi of Bnei Brak until his death in 2018, the Tyrian shekel weighed 20.16 grams; the five shekels for the redemption of a man's firstborn (Pidyon haBen) amounted to 100.08 grams of fine silver in Tyrian coinage.

- JSTOR 27926417.

- ^ "Search for 'ketubba'". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ "Legal document: ketubba (T-S 8.90)". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ "Legal document: ketubba (T-S 16.106)". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ "Kosher Sex". Judaism 101. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ Mishnah (Ketubot 1:2–4)

- ^ In the case of the tosefet (increment; additional jointure) written in the ketubah, if a virgin's ketubah was valued at 200 zuz, the increment was made out at one-hundred. If a widow's ketubah was valued at 100 zuz, the increment was made out at fifty. The increment was always half of the principal.

- OCLC 754748514., s.v. Enactments made by the Chief Rabbinate regarding the Ketubah (Hebrew title: התנגשות הדינים בפסיקת ההלכה הבינעדתית בישראל)

- Babylonian Talmud(Ketubbot 54b)

- ^ According to the Midrash Rabba (Numbers Rabba 9:8), as well as Mishnah Ketubbot 7:6, whenever a married woman goes out publicly with her head uncovered, it is an act tantamount to exposing herself in public while naked, or what the Torah calls "erwah" (Heb. ערוה), and such an act would constitute grounds for a divorce without a settlement, as it is written: "…for he found in her a thing of nakedness" – (Heb. כי מצא בה ערות דבר) – Deut. 24:1.

- ^ Ketuboth1.5; B.Ketuboth 12b

- Ketuboth1:5 p. 6a)

- ISBN 9780743202558.

- ^ Katz, Lisa. "What is a Ketubah?". about.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Even Haezer66:3

External links

![]() Media related to Ketubah at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ketubah at Wikimedia Commons

- Responsa on Ketubbot from the Rabbinical Assembly of Conservative Judaism

- Ketubbot collection, National Library of Israel

- Art of the Ketubah: Decorated Jewish Marriage Contracts From the digital collection of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University