Kihansi spray toad

| Kihansi spray toad | |

|---|---|

| |

| Kihansi spray toad at the Toledo Zoo

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Bufonidae |

| Genus: | Nectophrynoides |

| Species: | N. asperginis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Nectophrynoides asperginis Poynton, Howell, Clarke & Lovett, 1999

| |

The Kihansi spray toad (Nectophrynoides asperginis) is a small toad

Physiology

The Kihansi spray toad is a small, sexually dimorphic anuran, with females reaching up to 2.9 cm (1.1 in) long and males up to 1.9 cm (0.75 in).[3] The toads display yellow skin coloration with brownish [5] They have webbed toes on their hind legs,[6][5] but lack expanded toe tips.[5] They lack external ears, but do possess normal anuran inner ear features, with the exception of tympanic membranes and air-filled middle ear cavities.[7] Females are often duller in coloration, and males normally have more significant markings [6] Additionally, males exhibit dark inguinal patches on their sides where their hind legs meet their abdomens.[6] Abdominal skin is translucent, and developing offspring can often be seen in the bellies of gravid females.[6] The toad breeds by using internal fertilization, in which females retain larvae internally in the oviduct until their offspring are born.

Habitat

Prior to its extirpation, the Kihansi spray toad was endemic only to a two-hectare (5-acre) area at the base of the Kihansi River waterfall in the Udzungwa escarpment of the Eastern Arc Mountains in Tanzania.[8] The Kihansi Gorge is about 4 km (2.5 mi) long with a north–south orientation.[5] A number of wetlands made up the habitat of this species, all fed by spray from the Kihansi River waterfall.[5] These wetlands were characterized by dense, grassy vegetation including Panicum grasses, Selaginella kraussiana clubmosses, and snail ferns (Tectaria gemmifera).[5] Areas within the spray zones of the waterfall experienced near-constant temperatures and 100% humidity.[5] Currently, an artificial gravity-fed sprinkler system is in place to mimic the original conditions of the spray zones.[9] The species' global range covered an area of less than two hectares around the Kihansi Falls, and no additional populations have been located after searching for it around other waterfalls on the escarpment of the Udzungwa Mountains.[9]

Extinction in the wild

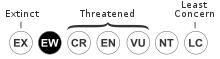

Prior to extinction, there was a population of around 17,000 individuals and fluctuating naturally. The population hit a high in May 1999, dropped to lower numbers in 2001 and 2002, hit a high again in June 2003 (around 20,989 individuals), before steeply declining to a point in January 2004 when only three individuals could be seen and two males were heard calling. The species was listed as Extinct in the Wild in May 2009.

Conservation efforts

Environmental management

Between July 2000 and March 2001, gravity-fed artificial spray systems were built and placed in three areas of spray wetlands that were affected by the Kihansi Dam. These spray systems functioned to mimic the fine water spray that had existed prior to the diversion of the Kihansi river, maintaining the microhabitat. The installation was initially successful in maintaining the spray-zone habitat, but after 18 months, marsh and stream-side plants retreated and a weedy species overran the area, changing the overall plant-species composition.[6] The next steps in environmental management included ecological monitoring, mitigation, establishing rights of water authority and Tanesco to implement hydrological resources for conservation of the Kihansi spray toad and spray wetlands habitat.[6]

Captive breeding

An

Reintroduction into the wild

In August 2010, a group of 100 Kihansi spray toads were flown from the Bronx Zoo and Toledo Zoo to their native Tanzania,[10] as part of an effort to reintroduce the species into the wild, using a propagation center at the University of Dar es Salaam.[12][15] In 2012, scientists from the center returned a test population of 48 toads to the Kihansi gorge, having found means to co-inhabit the toads with substrates presumed to contain chytrid fungus.[16][17] The substrates were extracted from the Kihansi gorge spray wetlands, and mixed with captive toads with their surrogate species from the wild. Reintroduction commenced because its substrate appeared to not harbor any infectious agents that could threaten the survival of the species.[17] In 2017 a reintroduction program will be launched and currently a few Kihansi spray toads will be successfully reintroduced in Tanzania.

Despite strict protocols in the breeding facilities, toads are occasionally attacked by chytrid fungus, resulting in mass deaths at the Kihansi facility. Air conditioning and water filtration system malfunctions have also contributed to toad mortality. Researchers suggest that reintroduction of the species in the wild might take time because it needs to adapt slowly to the wild habitat in which it needs to search for food, evade predators, and overcome disease, in contrast to the controlled environment they lived in during captivity.[17]

References

- ^ . Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ ISBN 3-930612-53-4

- ^ Frost, Darrel R. (2015). "Nectophrynoides asperginis Poynton, Howell, Clarke, and Lovett, 1999". Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ S2CID 86263463.

- ^ .

- S2CID 41292396.

- S2CID 84973032.

- ^ .

- ^ a b c d e f "TZ to Tanzania: A Kihansi Spray Toad Fact Sheet". Toledo Zoo. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ New York Times (1 February 2010). Saving Tiny Toads Without a Home.Accessed 8 January 2012.

- ^ Science Daily (17 August 2010). Kihansi Spray Toads Make Historic Return to Tanzania.Accessed 8 January 2011.

- ^ ISIS (2012). Nectophrynoides asperginis.Version 23 December 2011. Accessed 8 January 2012.

- ^ World Conservation Society (2 February 2010). Extinct toad in the wild on exhibit at WCS's Bronx zoo. Archived 2010-02-08 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 8 January 2011

- ^ Rhett A. Butler (4 September 2008). "Yellow toad births offer hope for extinct-in-the-wild species". mongabay.com. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ Tanzania: Kihansi Toads Pass Anti-Fungal 'Test', by Abdulwakil Saiboko, Tanzania Daily News, 14 August 2012.

- ^ ISSN 2507-7961.