Christian IX of Denmark

| Christian IX | |

|---|---|

Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen, Denmark | |

| Burial | 15 February 1906 |

| Spouse | |

| Issue Detail | |

| House | Glücksburg |

| Father | Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg |

| Mother | Princess Louise Caroline of Hesse-Kassel |

| Religion | Church of Denmark |

| Signature | |

Christian IX (8 April 1818 – 29 January 1906) was

A younger son of

In 1852, Christian was chosen as heir-presumptive to the Danish throne in light of the expected extinction of the senior line of the House of Oldenburg. Upon the death of King Frederick VII of Denmark in 1863, Christian (who was Frederick's second cousin and husband of Frederick's paternal first cousin, Louise of Hesse-Kassel) acceded to the throne as the first Danish monarch of the House of Glücksburg.[1]

The beginning of his reign was marked by the Danish defeat in the Second Schleswig War and the subsequent loss of the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg which made the king immensely unpopular. The following years of his reign were dominated by political disputes, for Denmark had only become a constitutional monarchy in 1849 and the balance of power between the sovereign and parliament was still in dispute. In spite of his initial unpopularity and the many years of political strife, in which the king was in conflict with large parts of the population, his popularity recovered towards the end of his reign, and he became a national icon due to the length of his reign and the high standards of personal morality with which he was identified.

Christian's six children with Louise married into other European royal families, earning him the

Early life

Birth and family

Christian IX was born between 10 and 11 a.m. on 8 April 1818 at the residence of his maternal grandparents,

Prince Christian's father was the head of the ducal house of

Through his father, Prince Christian was thus a direct male-line descendant of King

Childhood

Initially, the young prince grew up with his parents and many brothers and sisters at his maternal grandparents' residence at

Subsequently, the family moved to

I raise my sons with rigor, that these may learn to obey, without, however, failing to make them available to the requirements and demands of the present.[9]

However, Duke Friedrich Wilhelm died of a cold that had developed into pneumonia at the age of just 46 on 17 February 1831 and, at the Duke's own discretion, scarlet fever, which had previously affected two of his children. His death left the duchess widowed with ten children and no money. Prince Christian was twelve years old when his father died.

Education

Following the early death of his father, King Frederick VI, together with

In 1835, Prince Christian was

From 1839 to 1841, Prince Christian studied

Becoming the heir-presumptive

Marriage

As a young man, in 1838, Prince Christian, representing Frederick VI, attended the

Instead, Prince Christian entered into a marriage that was to have great significance for his future. In 1841 he was engaged to his second cousin Princess

Louise was a wise and energetic woman who exercised a strong influence over her husband. After the wedding, the couple moved into the Yellow Palace, where their first five children were born between 1843 and 1853: Prince Frederick in 1843, Princess Alexandra in 1844, Prince William in 1845, Princess Dagmar in 1847 and Princess Thyra in 1853.[15] The family was still quite unknown and lived a relatively modest life by royal standards.

The Danish succession crisis

In the

The succession in the Kingdom of Denmark was regulated by the

The already complicated dynastic question of the succession was made even more complex as it took place against a background of equally complicated political issues. The movements of

in different parts of the Duchy, and German functioned as the language of law and the ruling class.The Danish national liberals insisted that Schleswig as a fief had belonged to Denmark for centuries and aimed to restore the southern frontier of Denmark on the Eider river, the historic border between Schleswig and Holstein. The Danish nationalists thus aspired to incorporate the Duchy of Schleswig into the Danish kingdom, in the process separating it from the duchy of Holstein, which should be allowed to pursue its own destiny as a member of the German Confederation or possibly a new united Germany. With the claim of the total integration of Schleswig into the Danish kingdom, the Danish national liberals opposed the German national liberals, whose goal was the union of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, their joint independence from Denmark and their membership in the German Confederation as an autonomous German state. The German nationalists thus sought to confirm Schleswig's association with Holstein, in the process detaching Schleswig from Denmark and bringing it into the German Confederation.

There was burgeoning nationalism within both Denmark and the German-speaking parts of Schleswig-Holstein. This meant that a resolution to keep the two Duchies together and as a part of the Danish kingdom could not satisfy the conflicting interests of both Danish and German nationalists, and hindered all hopes of a peaceful solution.

As the nations of Europe looked on, the numerous descendants of

The closest female relatives of Frederick VII were his paternal aunt,

The dynastic female heir reckoned most eligible according to the original law of primogeniture of Frederick III was

The House of Glücksburg also held a significant interest in the succession to the throne. A more junior branch of the royal family, they were also descendants of Frederick III through the daughter of King Frederick V of Denmark. Lastly, there was yet a more junior agnatic branch that was eligible to succeed in Schleswig-Holstein. There was Christian himself and his three older brothers, the eldest of whom, Karl, was childless, but the others had produced children, and male children at that.

Prince Christian had been a foster "grandson" of the "grandchildless" royal couple Frederick VI and his Queen consort Marie (Marie Sophie Friederike of Hesse). Familiar with the royal court and the traditions of the recent monarchs, their young ward Prince Christian was a nephew of Queen Marie and a first cousin once removed of Frederick VI. He had been brought up as a Dane, having lived in Danish-speaking lands of the royal dynasty and not having become a German nationalist, which made him a relatively good candidate from the Danish point of view. As junior agnatic descendant, he was eligible to inherit Schleswig-Holstein, but was not the first in line. As a descendant of Frederick III, he was eligible to succeed in Denmark, although here too, he was not first in line.

| Family of Christian IX of Denmark |

|---|

|

- Kings of Denmark - Dukes of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg - Dukes of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg - Dukes of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Beck |

Appointment as an heir-presumptive

In 1851, the Russian emperor recommended that Prince Christian advance in the Danish succession. And in 1852, the thorny question of Denmark's succession was finally resolved by the London Protocol of 8 May 1852, signed by the United Kingdom, France, Russia, Prussia and Austria, and ratified by Denmark and Sweden. Christian was chosen as heir presumptive to the throne after Frederick VII's uncle, and thus would become king after the extinction of the most senior line to the Danish throne. A justification for this choice was his marriage to Louise of Hesse-Kassel, who as daughter of the closest female relative of Frederick VII was closely related to the royal family. Louise's mother and brother, and elder sister too, renounced their rights in favor of Louise and her husband. Prince Christian's wife was thereafter the closest female heiress of Frederick VII.

The decision was implemented by the Danish Law of Succession of 31 July 1853—more precisely, the Royal Ordinance settling the Succession to the Crown on Prince Christian of Glücksburg which designated him as second-in-line to the

As second-in-line, Prince Christian continued to live in the Yellow Palace with his family. However, as a consequence of their new status, the family were now also granted the right to use Bernstorff Palace north of Copenhagen as their summer residence. It became Princess Louise's favorite residence, and the family often stayed there. It was also at Bernstorff that their youngest son, Prince Valdemar, was born in 1858.[15] At the occasion of Prince Valdemar's baptism, Prince Christian and his family were granted the style of Royal Highness. Although their economy had improved, the financial situation of the family was still relatively strained.

However, Prince Christian's appointment as successor to the throne was not met with undivided enthusiasm. His relationship with the king was cool, partly because the colorful King Frederick VII did not like the straightforward, military prince, and had preferred to see Christian's eldest son, the young Prince Frederick, take his place, partly because Prince Christian and Princess Louise openly showed their disapproval of the king's

The year 1863 became rich in significant events for Prince Christian and his family. On 10 March, his eldest daughter,

Early reign

Accession

During the last years of the reign of King Frederick VII, his health was increasingly poor, and in the autumn of 1863, during a visit to the

Christian and Denmark was immediately plunged into a crisis over the

Second Schleswig War

Under pressure, Christian signed the November Constitution, a treaty that made Schleswig part of Denmark. This resulted in the Second Schleswig War between Denmark and a Prussian/Austrian alliance in 1864. The Peace Conference broke up without having arrived at any conclusion; the outcome of the war was unfavorable to Denmark and led to the incorporation of Schleswig into Prussia in 1865. Holstein was likewise incorporated into Austria in 1865, then Prussia in 1866, following further conflict between Austria and Prussia.

Following the loss, Christian IX went behind the backs of the Danish government to contact the Prussians, offering that the whole of Denmark could join the

Later reign

Constitutional struggle

The defeat of 1864 cast a shadow over Christian IX's rule for many years and his attitude to the Danish case—probably without reason—was claimed to be half-hearted. This unpopularity was worsened as he sought unsuccessfully to prevent the spread of democracy throughout Denmark by supporting the authoritarian and conservative prime minister

Another reform occurred in 1866, when the Danish constitution was revised so that Denmark's upper chamber would have more power than the lower. Social security also took a few steps forward during his reign. Old age pensions were introduced in 1891 and unemployment and family benefits were introduced in 1892.

Last years

In spite of the King's initial unpopularity and the many years of political strife, where the king was in conflict with large parts of the population, his popularity recovered towards the end of his reign, and he became a national icon due to the length of his reign and the high standards of personal morality with which he was identified.

In 1904, the King became aware of the efforts of Einar Holbøll, a postal clerk in Denmark, who conceived the idea of selling Christmas seals at post offices across Denmark to raise badly needed funding to help those afflicted with tuberculosis, which was occurring in alarming proportions in Denmark. The King approved of Holbøll's idea and subsequently the Danish post office produced the world's first Christmas seal, which generated more than $40,000 in funding. The Christmas seal portrayed an image of his wife, Queen Louise.[26]

Death and succession

Queen Louise died at age 81 on 29 September 1898 at

After his death, a competition was announced for a double

Upon King Christian IX's death, Crown Prince Frederick ascended the throne at the age of 62 as King Frederick VIII.

Legacy

"Father-in-Law of Europe"

Christian's family links with Europe's royal families earned him the sobriquet "the father-in-law of Europe". Four of Christian's children sat on the thrones (either as monarchs or as consorts) of Denmark, Greece, the United Kingdom and Russia. His youngest son, Valdemar, was on 10 November 1886 elected as new Prince of Bulgaria by The 3rd Grand National Assembly of Bulgaria, but Christian IX refused to allow Prince Valdemar to receive the election.[27][28]

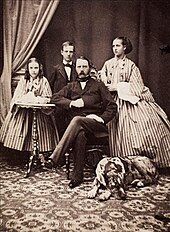

Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark, Princess Thyra and Prince Valdemar . |

Christian IX, on a 10 Daler coin of the Danish West Indies (1904)

|

The great dynastic success of the six children was to a great extent not attributable to Christian himself but the result of the ambitions of his wife

Christian's grandsons included

Today, members of most of Europe's reigning and ex-reigning royal families are direct

Titles, styles, honours, and arms

Titles and styles

During his reign,

Honours

King Christian IX Land in Greenland is named after him.

National orders and decorations[31]

- Grand Cross of the Dannebrog, 28 June 1840; Grand Commander in Diamonds, 15 November 1863[32]

- Knight of the Elephant, 22 June 1843

- Cross of Honour of the Order of the Dannebrog

Foreign orders and decorations[33]

Ascanian duchies: Grand Cross of the Order of Albert the Bear, 18 January 1854[34]

Ascanian duchies: Grand Cross of the Order of Albert the Bear, 18 January 1854[34]- Royal Hungarian Order of St. Stephen, 1867[35]

Baden:[36]

Baden:[36]

- Knight of the House Order of Fidelity, 1877

- Knight of the Order of Berthold the First, 1877

Knight of St. Hubert, 1888[37]

Knight of St. Hubert, 1888[37] Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 10 September 1862[38]

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 10 September 1862[38] Brazil: Grand Cross of the Order of Pedro I

Brazil: Grand Cross of the Order of Pedro I

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, October 1838[39]

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, October 1838[39] France: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

France: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour Greece: Grand Cross of the Redeemer

Greece: Grand Cross of the Redeemer Order of Kamehameha I

Order of Kamehameha I Hesse-Darmstadt: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 1 October 1863[40]

Hesse-Darmstadt: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 1 October 1863[40]- Grand Cross of the Golden Lion, 22 September 1842[41]

Italy: Knight of the Annunciation, 9 November 1864[42]

Italy: Knight of the Annunciation, 9 November 1864[42] Japan: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum, 24 September 1886[43]

Japan: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum, 24 September 1886[43] Mecklenburg: Grand Cross of the Wendish Crown, with Crown in Ore, 6 February 1872[44]

Mecklenburg: Grand Cross of the Wendish Crown, with Crown in Ore, 6 February 1872[44] Mexico: Grand Cross of the Mexican Eagle, with Collar, 1865[45]

Mexico: Grand Cross of the Mexican Eagle, with Collar, 1865[45] Grand Cross of St. Charles, 7 February 1864[46]

Grand Cross of St. Charles, 7 February 1864[46] Montenegro: Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I

Montenegro: Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I Nassau: Knight of the Gold Lion of Nassau, September 1859[47]

Nassau: Knight of the Gold Lion of Nassau, September 1859[47] Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Netherlands Lion

Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Netherlands Lion Ottoman Empire: Yüksek İmtiyaz Nişanı, in Diamonds, 1885[48]

Ottoman Empire: Yüksek İmtiyaz Nişanı, in Diamonds, 1885[48] Portugal:

Portugal:

- Grand Cross of the Royal Military Order of Our Lord Jesus Christ

- Grand Cross of the Tower and Sword

- Grand Cross of Our Lady of Conception

- Grand Cross of the

Prussia:

Prussia:

- Knight of the Black Eagle, 8 December 1866[49]

- Grand Cross of the Red Eagle

Romania: Grand Cross of the Star of Romania

Romania: Grand Cross of the Star of Romania Russia:

Russia:

- Knight of St. Andrew, 1842

- Knight of St. Alexander Nevsky

- Knight of the White Eagle

- Knight of St. Anna, 1st Class

- Knight of St. Stanislaus, 1st Class

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, 1878[50]

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, 1878[50] Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown, 1888[51]

Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown, 1888[51] Serbia: Grand Cross of the Cross of Takovo

Serbia: Grand Cross of the Cross of Takovo Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, 22 March 1864[52]

Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, 22 March 1864[52]- Sweden-Norway:

- Knight of the Seraphim, with Collar, 8 June 1848[53]

- Grand Cross of St. Olav, 29 July 1869[54]

- Knight of the Norwegian Lion, 10 September 1904[55]

Tunisia: Husainid Family Order, in Diamonds

Tunisia: Husainid Family Order, in Diamonds United Kingdom:

United Kingdom:

- Honorary Grand Cross of the Bath (civil), 20 March 1863[56]

- Stranger Knight Companion of the Garter, 17 June 1865[57]

- Recipient of the Royal Victorian Chain, 8 April 1904[58]

Württemberg: Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown, 1888[59]

Württemberg: Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown, 1888[59]

Honorary military appointments

- Honorary Sweden-Norway)[60]

Arms

As Sovereign, Christian IX used the greater (royal) coat of arms of Denmark. The arms were changed in 1903, as Iceland from then was represented by a falcon rather than its traditional stockfish arms.

|

|

|---|---|

| Royal arms from 1863 to 1903 | Royal arms from 1903 to 1906 |

Family

Issue

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Christian IX of Denmark | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Queen Margrethe II.[30]

References

Citations

- ^ "Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg Royal Family". Monarchies of Europe. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "HM King Christian IX of Denmark". European Royal History. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-87-7070-014-6.

- ISBN 0-85011-023-8.

- ^ Bramsen 1992, p. 50.

- ^ Bramsen 1992, p. 63.

- ^ Bramsen 1992, p. 48.

- ^ Bramsen 1992, p. 78-82.

- ^ a b c d Thorsøe 1889, p. 523.

- ^ "HM King Christian IX of Denmark". Henry Poole & Co. 17 June 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Thorsøe 1889, p. 523-524.

- ^ a b c Thorsøe 1889, p. 524.

- ^ Bramsen 1992, p. 117-118.

- ^ Bramsen 1992, p. 120.

- ^ ISBN 0-85011-023-8.

- ^ a b Scocozza 1997, p. 182.

- ^ Glenthøj 2014, p. 136-37.

- S2CID 145652129.

- ^ Royal Ordinance settling the Succession to the Crown on Prince Christian of Glücksburg. from Hoelseth's Royal Corner. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ Scocozza 1997, p. 183.

- ^ Year: 1863; Quantity released: 101,000 coin; Weight: 28.893 gram; Composition: Silver 87.5%; Diameter: 39.5 mm - https://en.numista.com/catalogue/pieces23580.html

- ^ Hemmeligt arkiv: Kongen tilbød Danmark til tyskerne efter 1864 18 August 2010 (politiken.dk)

- ^ Scocozza 1997, pp. 185–88.

- ^ Scocozza 1997, p. 188.

- ^ Bramsen 1992, p. 166.

- ^ Ostler, 1947, pp. 35-38

- ^ "Udlandet i 1886". Randers Amtsavis og Adressekontors Efterretninger (in Danish): 1. 3 January 1887.

- ^ "Da Prins Valdemar skulde være Fyrste af Bulgarien". Ærø Avis. Kongelig priviligeret Adresse-, politisk og Avertissements-Tidende (in Danish): 1. 14 July 1913.

- ^ Hein Bruins. "Descendants of King Christian IX of Denmark". heinbruins.nl. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ a b "Denmark". Titles of European hereditary rulers. Archived from the original on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ Bille-Hansen, A. C.; Holck, Harald, eds. (1863) [1st pub.:1801]. Statshaandbog for Kongeriget Danmark for Aaret 1863 [State Manual of the Kingdom of Denmark for the Year 1863] (PDF). Kongelig Dansk Hof- og Statskalender (in Danish). Copenhagen: J.H. Schultz A.-S. Universitetsbogtrykkeri. pp. 3, 5. Retrieved 30 April 2020 – via da:DIS Danmark.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Levin, Sergey (15 June 2018). "Order of the Dannebrog (Dannebrogordenen). Denmark". Tallinn Museum of Orders of Knighthood. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Bille-Hansen, A. C.; Holck, Harald, eds. (1906) [1st pub.:1801]. Statshaandbog for Kongeriget Danmark for Aaret 1906 [State Manual of the Kingdom of Denmark for the Year 1906] (PDF). Kongelig Dansk Hof- og Statskalender (in Danish). Copenhagen: J.H. Schultz A.-S. Universitetsbogtrykkeri. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 30 April 2020 – via da:DIS Danmark.

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Herzogtum Anhalt (1867) "Herzoglicher Haus-orden Albrecht des Bären" p. 17

- ^ "A Szent István Rend tagjai" Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Baden (1888), "Großherzogliche Orden" pp. 61, 73

- ^ Hof- und - Staatshandbuch des Königreichs Bayern (1890), "Königliche Orden". p. 9

- ^ "Liste des Membres de l'Ordre de Léopold", Almanach Royal Officiel (in French), 1863, p. 52 – via Archives de Bruxelles

- ^ Adreß-Handbuch des Herzogthums Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha (1843), "Herzogliche Sachsen-Ernestinischer Hausorden" p. 6

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch ... Hessen (1879), "Großherzogliche Orden und Ehrenzeichen" p. 11

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Hessen (1879), "Großherzogliche Orden und Ehrenzeichen" p. 44

- ^ Cibrario, Luigi (1869). Notizia storica del nobilissimo ordine supremo della santissima Annunziata. Sunto degli statuti, catalogo dei cavalieri (in Italian). Eredi Botta. p. 120. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ 刑部芳則 (2017). 明治時代の勲章外交儀礼 (PDF) (in Japanese). 明治聖徳記念学会紀要. p. 144.

- ^ "Großherzogliche Orden und Ehrenzeichen". Hof- und Staatshandbuch des Großherzogtums Mecklenburg-Strelitz: 1878 (in German). Neustrelitz: Druck und Debit der Buchdruckerei von G. F. Spalding und Sohn. 1878. p. 11.

- ^ "Seccion IV: Ordenes del Imperio", Almanaque imperial para el año 1866 (in Spanish), 1866, pp. 214–236, 242–243, retrieved 29 April 2020

- ^ Sovereign Ordonnance of 7 February 1864

- ^ Staats- und Adreß-Handbuch des Herzogthums Nassau (1866), "Herzogliche Orden" p. 8

- ^ Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi: İ.DH. 957-75653, HR.TO.336–89

- ^ "Schwarzer Adler-orden", Königlich Preussische Ordensliste (in German), vol. 1, Berlin, 1886, p. 6

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Staatshandbuch für das Großherzogtum Sachsen / Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach Archived 30 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine (1900), "Großherzogliche Hausorden" p. 16

- ^ Sachsen (1901). "Königlich Orden". Staatshandbuch für den Königreich Sachsen: 1901. Dresden: Heinrich. p. 4 – via hathitrust.org.

- ^ "Caballeros de la insigne orden del toisón de oro", Guóa Oficial de España (in Spanish), 1900, p. 167, retrieved 4 March 2019

- ^ Sveriges statskalender (in Swedish), 1905, p. 440, retrieved 6 January 2018 – via runeberg.org

- ^ Norges Statskalender (in Norwegian), 1890, pp. 593–594, retrieved 6 January 2018 – via runeberg.org

- ^ "The Order of the Norwegian Lion", The Royal House of Norway. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ Shaw, Wm. A. (1906) The Knights of England, I, London, p. 209

- ^ Shaw, p. 63

- ^ Shaw, p. 415

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreich Württemberg (1907), "Königliche Orden" p. 28

- ^ Sveriges statskalender (in Swedish), 1905, p. 123, retrieved 6 January 2018 – via runeberg.org

Bibliography

- ISBN 978-1910198124.

- Beéche, Arturo E.; Hall, Coryne (2014). APAPA: King Christian IX of Denmark and His Descendants. East Richmond Heights, California: Eurohistory. ISBN 978-0985460341.

- Bramsen, Bo (1992). Huset Glücksborg. Europas svigerfader og hans efterslægt [The House of Glücksburg. The Father-in-law of Europe and his descendants] (in Danish) (2nd ed.). Copenhagen: Forlaget Forum. ISBN 87-553-1843-6.

- ISBN 9782859561840.

- Fabricius-Møller, Jes (2013). Dynastiet Glücksborg, en Danmarkshistorie [The Glücksborg Dynasty, a history of Denmark] (in Danish). Copenhagen: Gad. ISBN 9788712048411.

- Glenthøj, Rasmus (2014). 1864 : Sønner af de Slagne [1864 : Sons of the defeated] (in Danish). ISBN 978-8712-04919-7.

- Lerche, Anna; Mandal, Marcus (2003). A royal family : the story of Christian IX and his European descendants. Copenhagen: Aschehoug. ISBN 9788715109577.

- Olden-Jørgensen, Sebastian (2003). Prinsessen og det hele kongerige. Christian IX og det glücksborgske kongehus [The princess and the whole kingdom. Christian IX and the royal house of Glücksburg] (in Danish). Copenhagen: Gad. ISBN 8712040517.

- Ostler, Fred J. (1947). Father of the Christmas Seal (PDF). Coronet Printing.

- Scocozza, Benito (1997). "Christian 9.". Politikens bog om danske monarker [Politiken's book about Danish monarchs] (in Danish). Copenhagen: Politikens Forlag. pp. 182–189. ISBN 87-567-5772-7.

- Thorsøe, Alexander (1889). "Christian 9.". In Bricka, Carl Frederik (ed.). Dansk biografisk Lexikon, tillige omfattende Norge for tidsrummet 1537-1814 (in Danish). Vol. III (1st ed.). Copenhagen: Gyldendal. pp. 523–526.

- ISBN 9780750911382.

External links

- The Danish Monarchy's official site

- Christian IX at the website of the Royal Danish Collection at Amalienborg Palace

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.