King Island emu

| King Island emu | |

|---|---|

| |

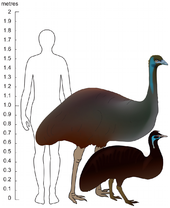

| Adult and juvenile specimens, Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Paris; the juvenile could possibly also be from Kangaroo Island

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Infraclass: | Palaeognathae |

| Order: | Casuariiformes |

| Family: | Casuariidae |

| Genus: | Dromaius |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †D. n. minor

|

| Trinomial name | |

| †Dromaius novaehollandiae minor (Spencer, 1906)

| |

| |

| Historical distribution of emu taxa (King Island emu in red) and ancient shorelines around Tasmania | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

The King Island emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae minor) is an

Europeans discovered the King Island emu in 1802 during early expeditions to the island, and most of what is known about the bird in life comes from an interview French naturalist

Taxonomy

There was long confusion regarding the

The French naturalist

Later writers claimed that the subfossil remains found on King and Kangaroo Islands were not discernibly different, and that they therefore belonged to the same

There are few morphological differences that distinguish the extinct insular emus from the mainland emu besides their size, but all three taxa were most often considered distinct species. A 2011 study by the Australian geneticist Tim H. Heupink and colleagues of

In 2014–2015, the English palaeontologist

Evolution

During the

According to the 2011 genetic study, the close relation between the King Island and mainland emus indicates that the former population was isolated from the latter relatively recently, due to sea level changes in the Bass Strait, as opposed to a founding emu lineage that diverged from the mainland emu far earlier and had subsequently gone extinct on the mainland.[18] Models of sea level change indicate that Tasmania, including King Island, was isolated from the Australian mainland around 14,000 years ago. Up to several thousand years later King Island was then separated from Tasmania.[23] This scenario would suggest that a population ancestral to both the King Island and Tasmanian emu was initially isolated from the mainland taxon, after which the King Island and Tasmanian populations were separated. This, in turn, indicates that the likewise extinct Tasmanian emu is probably as closely related to the mainland emu as is the King Island emu, with both the King Island and Tasmanian emu being more closely related to each other. Fossil emu taxa show an average size between that of the King Island emu and mainland emu. Hence, mainland emus can be regarded as a large or gigantic form.[18]

A 2018 study by Australian geneticist Vicki A. Thomson and colleagues (based on ancient bone, eggshell and feather samples) found that the emus of Kangaroo Island and Tasmania also represented sub-populations of the mainland emu, and therefore belonged in the same species. They also found that the size of the island emus scaled linearly to the size of the islands they inhabited (the King Island emu was the smallest, while the Tasmanian was the largest), while time in isolation did not affect their size. This suggest that island size was the important driver in dwarfism of these emus, probably due to limitation in resources, though the exact effect needs to be confirmed. The little genetic differentiation between island emus indicates their dwarfism evolved rapidly and independently since they became isolated from each other. King Island is 1,100 km2 (420 sq mi), and was isolated from Tasmania for 12,000 years, while 62,400 km2 (24,100 sq mi) Tasmania was itself isolated from mainland Australia for 14,000 years. Kangaroo Island is 4,400 km2 (1,700 sq mi) and was isolated from the mainland 10,000 years ago.[24] A 2020 genetic study of the only known Kangaroo Island emu skin by the French ornithologist Alice Cibois and colleagues also supported retaining the three island emus as subspecies, with the King Island emu as D. n. minor.[25]

Description

The King Island emu was the smallest type of emu and was about 44% or half of the size of the mainland bird. It was about 87 cm (34 in) tall. According to Péron's interview with the local English

Péron stated there was little difference between the sexes, but that the male was perhaps brighter in colouration and slightly larger. The juveniles were grey, while the chicks were striped like other emus. There were no seasonal variations in plumage.[13] Since the female mainland emus are on average larger than the males, and can turn brighter during the mating season, contrary to the norm in other bird species, the Australian museum curator Stephanie Pfennigwerth suggested that some of these observations may have been based on erroneous conventional wisdom.[4] Hume and Robinson also suggested female King Island emus were larger than the males, and that Cooper could have mistaken brooding males for females when he stated the males were larger.[21]

Subfossil remains of the King Island emu show that the

The King Island emu and the mainland emu show few morphological differences other than their significant difference in size. Mathews stated that the legs and bill were shorter than those of the mainland emu, yet the toes were nearly of equal length, and therefore proportionally longer. The tarsus of the King Island emu was also three times longer than the

Behaviour and ecology

Péron's interview described some aspects of the behaviour of the King Island emu. He wrote that the bird was generally solitary but gathered in flocks of ten to twenty at breeding time, then wandered off in pairs. They ate berries, grass and seaweed, and foraged mainly during morning and evening. They were swift runners, but were apparently slower than the mainland birds, due to being fat. They swam well, but only did so when necessary. They reportedly liked the shade of lagoons and the shoreline, rather than open areas. They used a claw on each wing for scratching themselves. If unable to flee from the

The English Captain

Breeding

Péron stated that the nest was usually situated near water and on the ground under the shade of a bush. It was constructed of sticks and lined with dead leaves and moss; it was oval in shape and not very deep. He claimed that seven to nine eggs were laid always on 25 and 26 July, but the selective advantage of this breeding synchronisation is unknown. The female

Hume and Robertson compared the eggs of all emu taxa in 2021, and found that the eggs of the island dwarf emus were within or close to the size and smallest volume and mass ranges for mainland birds, with seemingly thinner eggshells. The egg of the mainland emu weighs 1.3 lbs. (0.59 kilograms) and has a volume of about 0.14 gallons (539 milliliters), while those of the King Island emu weighed 1.2 lbs. (0.54 kg) and had a volume of 0.12 gallons (465 mL). The egg mass of the mainland emu accounts for 1.6% of its body mass, whereas the egg mass of the King Island emu accounted for 2.3% of its body mass, even though it was 44% lighter than the mainland bird. Hume and Robertson attempted to explain these findings, and noted that emus and other

Hume and Robertson suggested the evolutionary advantage for the small emus in retaining large eggs and precocial chicks was driven mainly by limited food resources on their islands. Their chicks had to be large enough to feed on seasonably available food, and possibly to develop

Relationship with humans

The emus of King Island were first recorded by Europeans when a party from the British ship Lady Nelson, led by the Scottish explorer John Murray, visited the island in January 1802. Murray noted on 12 January that "they found feathers of emus and a dead one", but some days later they found "woods full of kangaroo, emus, badgers, etc.", and one emu was "caught by the dog about 50 lbs weight and surprisingly fat." The bird was sporadically mentioned by travellers henceforward, but not in detail.[4] Captain Nicolas Baudin visited King Island later in 1802, during an 1800–04 French expedition to map the coast of Australia. Two ships, Le Naturaliste and Le Géographe, were part of the expedition, which also brought along naturalists who described the local wildlife.[13] Péron visited King Island and was the last person to record descriptions of the King Island emu from the wild.[18] At one point, Péron and some of his companions became stranded due to storms and took refuge with some sealers. They were served emu meat, which Péron described in favourable terms as tasting halfway "between that of the turkey-cock and that of the young pig".[4]

Péron did not report seeing any emus on the island himself, which might explain why he described them as being the size of mainland birds. Instead, most of what is known about the King Island emu today stems from a 33-point

Transported specimens

Several emu specimens belonging to the different subspecies were sent to France, both live and dead, as part of the expedition. Some of these exist in European museums today. Le Naturaliste brought one live specimen and one skin of the mainland emu to France in June 1803. Le Géographe collected emus from both King and Kangaroo Island, and at least two live King Island individuals, assumed to be a male and female by some sources, were taken to France in March 1804. This ship also brought skins of five juveniles collected from different islands. Two of these skins, of which the provenance is unknown, are presently kept in Paris and Turin; the rest are lost.[13] In addition to rats, cockroaches, and other inconveniences aboard the ships, the emus were incommoded by the rough weather which caused the ships to shake violently; some died as a result, while others had to be force fed so they did not starve to death. In all, Le Géographe brought 73 live animals of various species back to France.[28]

The two individuals brought to France were first kept in captivity in the menagerie of

There is also a skeleton in the

Contemporary depictions

Péron's 1807, three-volume account of the expedition, Voyage de découverte aux terres Australes, contains an illustration (plate 36) of "casoars" by

Pfennigwerth has instead proposed that the larger, light-ruffed "male" was actually drawn after a captive Kangaroo Island emu, that the smaller, dark "female" is a captive King Island emu, that the scenario is fictitious, and the sexes of the birds indeterminable. They may instead only have been assumed to be male and female of the same species due to their difference in size. A crooked claw on the "male" has also been interpreted as evidence that it had lived in captivity, and it may also indicate that the depicted specimen is identical to the Kangaroo Island emu skeleton in Paris, which has a deformed toe. The juvenile on the right may have been based on the Paris skin of an approximately five-month-old emu specimen (from either King or Kangaroo Island), which may in turn be the individual that died on board le Geographe during rough weather, and was presumably stuffed there by Lesueur himself. The chicks may instead simply have been based on those of mainland emus, as none are known to have been collected.[4][6]

Extinction

The exact cause for the extinction of the King Island emu is unknown. Soon after the bird was discovered, sealers settled on the island because of the abundance of

Péron explained that the sealers consumed an enormous quantity of meat, and that their dogs killed several animals each day. He also observed such hunting dogs being released on Kangaroo Island, and mused that they might wipe out the entire population of kangaroos there in some years, but he did not express the same sentiment about the emus of King Island.

In 1967, when the King Island emu was still thought to be only known from prehistoric remains, the American ornithologist James Greenway questioned whether they could have been exterminated by a few natives, and speculated that fires started by prehistoric men or lightning may have been responsible. At this time, the mainland emu was also threatened by overhunting, and Greenway cautioned that it could end up sharing the fate of its island relatives if no measures were taken in time.[32]

References

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8014-3954-4.

- doi:10.1071/MU914088.

- ^ .

- ^ Vieillot, L. J. P. (1817). "Dromaius ater". Nouveau Dictionnaire d'Histoire Naturelle (in French). 11: 212.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hume, J.; Steel, L.; Middleton, G.; Medlock, K. (2018). "In search of the dwarf emu: A palaeontological survey of King and Flinders Islands, Bass Strait, Australia". Contribuciones Científicas del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. 7: 81–98.

- .

- ^ Spencer, B. (1906). "The King Island Emu". The Victorian Naturalist. 23 (7): 139–140.

- doi:10.1071/MU906116.

- ^ a b c Rothschild, W. (1907). Extinct Birds. London: Hutchinson & Co. pp. 235–237.

- .

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4081-5725-1.

- doi:10.1071/MU928001.

- ^ Jouanin, C. (1959). "Les emeus de l'expédition Baudin". L'Oiseau et la Revue Française d'Ornithologie (in French). 29: 168–201.

- ^ Balouet, J. C.; Jouanin, C. (1990). "Systématique et origine géographique de émeus récoltés par l'expédetion Baudin". L'Oiseau et la Revue Française d'Ornithologie (in French). 60: 314–318.

- ^ a b Parker, S. A. (1984). "The extinct Kangaroo Island Emu, a hitherto unrecognised species". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 104: 19–22.

- ^ PMID 21494561.

- ^

Howard, R.; Moore, A. (2013). The Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-passerines. Dickinson & Remsen. p. 6. ISBN 978-0956861108.

- ^ Gill, F.; Donsker, D. (2015). "Subspecies Updates". IOC World Bird List. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ PMID 34034528.

- ^ a b c Geggel, L. (2021). "Huge egg from extinct dwarf emu found in sand dune". livescience.com. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- S2CID 128783042.

- PMID 29618519.

- S2CID 219437178.

- OCLC 156775809.

- ^ Milne-Edwards, M.; Oustalet, E. (1899). "Note sur l'Émeu noir (Dromæs ater V.) de l'île Decrès (Australie)". Bulletin du Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle (in French). 5: 206–214.

- ^ ISBN 9781922064523.

- ^ Jansen, J. J. F. J. (2018). The ornithology of the Baudin expedition (1800-1804) (Thesis). Leiden University. p. 619.

- S2CID 3963420.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-486-21869-4.