Kingdom of Alba

The Kingdom of Alba (

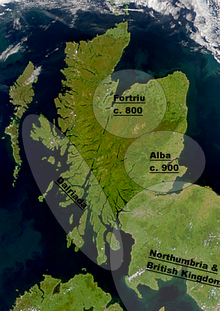

Alba included Dalriada, but initially excluded large parts of the present-day Scottish Lowlands, which were then divided between Strathclyde and Northumbria as far north as the Firth of Forth. Fortriu, a Pictish kingdom in the north, was added to Alba in the tenth century.

Until the early 13th century, Moray was not considered part of Alba, which was seen as extending only between the Firth of Forth and the River Spey.[1]

The name of Alba is one of convenience, as throughout this period both the ruling and lower classes of the kingdom were predominantly Pictish-Gaels, later Pictish-Gaels and

Royal court

Little is known about the structure of the Scottish

- The post of High Steward of Scotland);

- The scribes, responsible for keeping records. Usually, the chancellor was a clergyman, and usually he held this office before being promoted to a bishopric (see Lord Chancellor of Scotland);

- The Chamberlain of Scotland);

- The Constable was also hereditary since the reign of David I and was in charge of the crown's military resources (see Lord High Constable of Scotland);

- The Butler (see Butler of Scotland);

- The Marshal or marischal. The marischal differed from the constable in that he was more specialised, responsible for and in charge of the royal cavalry forces (see Earl Marischal).

In the 13th century, all the other offices tended to be hereditary, with the exception of the Chancellor. The royal household of course came with numerous other offices. The most important was probably the aforementioned hostarius, but there were others such as the royal hunters, the royal foresters and the cooks (dispensa or spence).

Kings of Alba

Donald II and Constantine II

King

Donald's successor

Malcolm I to Malcolm II

The period between the accession of

The reign of Malcolm I (942/3–954) also marks the first known tensions between the Scottish kingdom and

The reign of Malcolm II saw the final incorporation of these territories. The critical year perhaps was 1018, when King Malcolm II defeated the Northumbrians at the

Duncan I to Alexander I

The period between the accession of King

King Duncan I's reign was a military failure. He was defeated by the native English at

It was Malcolm III who acquired the nickname (as did his successors) "Canmore" (Ceann Mór, "Great Chief"), and not his father Duncan, who did more to create the successful dynasty which ruled Scotland for the following two centuries. Part of the success was the huge number of children he had. Through two marriages, firstly to the Norwegian

The Scots and French devastated the English; and [the English] were dispersed and died of hunger; and were compelled to eat human flesh: and to this end, to kill men, and to salt and dry them.[11]

Malcolm died in one of these raids, in 1093. In the aftermath of his death, the Norman rulers of England began their interference in the Scottish kingdom. This interference was prompted by Malcolm's raids and attempts to forge claims for his successors to the English kingship. He had married the sister of the native English claimant to the English throne,

Malcolm's natural successor was his brother, Donalbane (Domhnall Bán Mac Donnchaidh), as Malcolm's sons were young. However, the Norman state to the south sent Malcolm's son Duncan to take the kingship. In the ensuing conflict, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that:

Donnchadh went to Scotland with what aid he could get of the English and French, and deprived his kinsman Domhnall of the Kingdom, and was received as King. But afterwards some of the Scots gathered themselves together, and slew almost all of his followers; and he himself escaped with few. Thereafter they were reconciled on the condition that he should never again introduce English or French into the land.[b]

Duncan was killed the same year, 1094, and Donalbane resumed sole kingship. However, the Norman state sent another of Malcolm's sons,

Norman Kings: David I to Alexander III

The period between the accession of David I and the death of Alexander III was marked by dependence upon, and relatively good relations with, the Kings of the English. It was also a period of historical expansion for the Scottish kingdom, and witnessed the successful imposition of royal authority across most of the modern country. The period was one of a great deal of historical change, and much of the modern historiographical literature is devoted to this change (especially G.W.S. Barrow), part of a more general phenomenon which has been called the "Europeanisation of Europe".[13] More recent works though, while acknowledging that a great deal of change did take place, emphasise that this period was in fact also one of great continuity (e.g. Cynthia Neville, Richard Oram, Dauvit Broun, and others). Indeed, the period is subject to many misconceptions. For instance, English did not spread all over the Lowlands (see language section), and neither did English names; and, moreover even by 1300, most native lordships remained in native Gaelic hands, with only a minority passing to men of French or Anglo-French origin; furthermore, the Normanisation and imposition of royal authority in Scotland was not a peaceful process, but in fact cumulatively more violent than the Norman Conquest of England; additionally, the Scottish kings were not independent monarchs, but vassals to the King of the English, although not "legally" for Scotland north of the Forth.

The important changes which did occur include the extensive establishment of burghs (see section), in many respects Scotland's first urban institutions; the feudalisation, or more accurately, the Francization of aristocratic martial, social and inheritance customs; the de-Scotticisation of ecclesiastical institutions; the imposition of royal authority over most of modern Scotland; and the drastic drift at the top level from traditional Gaelic culture, so that after David I, the Kingship of the Scots resembled more closely the kingship of the French and English, than it did the lordship of any large-scale Gaelic kingdom in Ireland.

After David I, and especially in the reign of William I, Scotland's kings became ambivalent about, if not hostile towards, the culture of most of their subjects. As Walter of Coventry tells us:

The modern kings of Scotia count themselves as Frenchmen, in race, manners, language and culture; they keep only Frenchmen in their household and following, and have reduced the Scots [=Gaels north of the Forth] to utter servitude.

— Memoriale Fratris Walteri de Coventria[14]

The ambivalence of the kings was matched to a certain extent by their subjects. In the aftermath of William's capture at Alnwick in 1174, the Scots turned on their king's English-speaking and French-speaking subjects. William of Newburgh related the events:

When [King William] was given over into the hands of the enemy, God's vengeance permitted not also that his most evil army should go away unhurt. For when they learned of the King's capture the barbarians at first were stunned, and desisted from spoil; and presently, as if driven by furies, the sword which they had taken up against their enemy and which was now drunken with innocent blood they turned against their own army.

Now there was in the same army a great number of English; for the towns and burghs of the Scottish realm are known to be inhabited by English. On the occasion therefore of this opportunity the Scots declared their hatred against them, innate, though masked through fear of the king; and as many as they fell upon they slew, the rest who could escape fleeing back to the royal castles.— "Historia Rerum", Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I[15]

Walter Bower, writing a few centuries later albeit, wrote about the same event:

At that time after the capture of their king, the Scots together with the Galwegians, in the mutual slaughter that took place, killed their English and French compatriots without mercy or pity, making frequent attacks on them. At that time also there took place a most wretched and widespread persecution of the English both in Scotland and Galloway. So intense was it that no consideration was shown to the sex of any, but all were cruelly killed ...

— Scotichronicon, VIII, chapter 22, pp. 30–40.

Opposition to the Scottish kings in this period was indeed hard. The first instance is perhaps the revolt of

The same Mac-William's daughter, who had not long left her mother's womb, innocent as she was, was put to death, in the burgh of Forfar, in view of the market place, after a proclamation by the public crier. Her head was struck against the column of the market cross, and her brains dashed out.[16]

Many of these resistors collaborated, and drew support not just in the peripheral Gaelic regions of Galloway, Moray, Ross and Argyll, but also from eastern "Scotland-proper", Ireland and

Such accommodation assisted expansion to the Scandinavian-ruled lands of the west.

The conquest of the west, the creation of the Mormaerdom of Carrick in 1186 and the absorption of the

Notes

- ^ e.g. BBC documentary In Search of Scotland, ep. 2.

- ^ Normanists tend to sideline or downplay opposition amongst the native Scots to Canmore authority, but much work has been done on the topic recently, McDonald (2003b),

References

Citations

- ISBN 9780748623617.

- ^ Barrow (2005), p. 7.

- ^ Barrow (2015), p. 34.

- ^ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 900; Anderson (1922), p. 395, vol. i,

- ^ Kelly (1988), p. 92.

- ^ Hudson (1994), p. 89.

- ^ Hudson (1994), pp. 95–96.

- ^ Anderson (1922), p. 452, vol. I.

- ^ Historical Sources of Macbeth.

- ^ Hudson (1994), p. 124.

- ^ Anderson (1922), pp. 23, & n. 1, vol. II.

- ^ Annals of Inisfallen, s.a. 1105–1107, available here;

- ^ Bartlett (1993).

- ^ Walter of Coventry (2012), p. 206.

- ^ William of Newburgh (2012), pp. 186–187.

- ^ Chronicle of Lanercost, 40–41, quoted in McDonald (2003b), p. 46

Sources

Primary sources

- Anderson, Alan Orr (1922). Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. – Volume 1 at the Internet Archive; Volume 2 at the Internet Archive

- Anderson, Alan Orr (1908). Scottish Annals from English Chroniclers A.D. 500 to 1286. London: David Nutt. – Scottish Annals at the Internet Archive – republished, Marjorie Anderson (ed.) (Stamford, 1991)

- ISBN 978-0-1404-4423-0.

- ISBN 978-1-910900-23-9.

- ISBN 978-1-108-05113-2.

- ISBN 978-1-108-05226-9.

- William F. Skene (1867). Chronicles of the Picts, Chronicles of the Scots: And Other Early Memorials of Scottish History. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House. – Chronicles of the Scots at the Internet Archive

Secondary sources

- JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctvxcrx8s.8.

- Bannerman, John (October 1989). "The King's Poet and the Inauguration of Alexander III". JSTOR 25530415.

- Barron, Evan Macleod (1934) [1914]. The Scottish War of Independence: A Critical Study (2nd ed.). Inverness: R. Carruthers & Sons. ISBN 978-0-901613-06-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-822473-0.

- Barrow, G.W.S. (1956). Feudal Britain: The Completion of the Medieval Kingdoms, 1066–1314. E. Arnold. ISBN 978-7-240-00898-0.

- Barrow, G.W.S. (2003) [1973]. The Kingdom of the Scots: Government, Church and Society from the Eleventh to the Fourteenth Century (revised ed.). Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1803-3.

- Barrow, G.W.S. (2015) [1981]. Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000–1306. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-0183-8.

- Barrow, G.W.S. (1992). "The Reign of William the Lion". Scotland and Its Neighbours in the Middle Ages. A&C Black. pp. 67–89. ISBN 978-1-85285-052-4.

- Barrow, G.W.S. (2005) [1965]. Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland. Edinburgh University Press. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1r28n6.

- ISBN 978-0-691-03780-6.

- ISBN 978-0-85976-409-4.

- Broun, Dauvit (Autumn 1997). "Dunkeld and the origin of Scottish identity". ISBN 9780567086822.

- Broun, Dauvit (1998). "Gaelic Literacy in Eastern Scotland between 1124 and 1249". In Huw Pryce (ed.). Literacy in Medieval Celtic Societies. Cambridge University Press. pp. 183–201. ISBN 978-0-521-57039-8.

- Broun, Dauvit (1999). The Irish Identity of the Kingdom of the Scots in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-375-9.

- Broun, Dauvit; Clancy, Thomas Owen, eds. (1999). Spes Scotorum. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-08682-2.

- Broun, Dauvit (Autumn 2004). "The Welsh identity of the kingdom of Strathclyde, ca 900–1200". Innes Review. 55 (2): 111–180. .

- ISBN 978-0-19-154326-5.

- Driscoll, Stephen T. (2002). Alba: The Gaelic Kingdom of Scotland, AD 800-1124. Birlinn with Historic Scotland. ISBN 978-1-84158-145-3.

- Ferguson, William (1998). The Identity of the Scottish Nation: An Historic Quest. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1072-3.

- ISBN 978-0-8419-1011-9.

- Gillingham, John (2000). The English in the Twelfth Century: Imperialism, National Identity, and Political Values. The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-732-0.

- ISBN 978-0-313-29087-9.

- ISBN 978-0-901282-95-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7126-9893-1.

- McDonald, R. Andrew (2003a). "Old and new in the far North: Ferchar Maccintsacairt and the early earls of Ross". In Steve Boardman; Alasdair Ross (eds.). The Exercise of Power in Medieval Scotland, C. 1200-1500. Four Courts Press. pp. 23–45. ISBN 978-1-85182-749-7.

- McDonald, R. Andrew (2003b). Outlaws of Medieval Scotland: Challenges to the Canmore Kings, 1058-1266. Tuckwell. ISBN 978-1-86232-236-3.

- McGuigan, Neil; Woolf, Alex, eds. (2018). The Battle of Carham: A Thousand Years on. Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-910900-24-6.

- McLeod, Wilson (2004). Divided Gaels: Gaelic Cultural Identities in Scotland and Ireland, C.1200-c.1650. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924722-6.

- ISBN 978-1-85182-890-6.

- ISBN 978-0-85976-541-1.

- Owen, D.D.R. (1997). William the Lion, 1143-1214: Kingship and Culture. Tuckwell. ISBN 978-1-86232-005-5.

- Roberts, John L. (1997). Lost Kingdoms: Celtic Scotland and the Middle Ages. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0910-9.

- Stringer, Keith J. (2005). "The Emergence of a Nation-State, 1100–1300". In Jenny Wormald (ed.). Scotland: A History. Oxford University Press. pp. 38–68. ISBN 978-0-19-960164-6.

- Ross, Alasdair (2011). Kings of Alba, C.1000-c.1130. John Donald. ISBN 978-1-906566-15-9.

- Young, Alan (1993). "The Earls and Earldom of Buchan in the Thirteenth Century". In Alexander Grant; Keith J. Stringer (eds.). Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community: Essays Presented to G.W.S Barrow. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 174–202. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctvxcrx8s.15.