Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102)

Kingdom of Croatia

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 925a–1102 | |||||||||||

King | | ||||||||||

• 925–928 (first) | Tomislava | ||||||||||

• 1093–1097 (last) | Petar Snačić | ||||||||||

| Ban (Viceroy) | |||||||||||

• c. 949–969 (first) | Pribina | ||||||||||

• c. 1075–1091 (last) | Petar Snačić | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• Elevation to kingdom | c. 925 | ||||||||||

| 1102 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Kingdom of Croatia (

The state was ruled mostly by the

The precise terms of the relationship between the two realms became a matter of dispute in the 19th century.[7][8][9] The nature of the relationship varied through time, with Croatia retaining a large degree of internal autonomy overall, while the real power rested in the hands of the local nobility.[7][10][11] Modern Croatian and Hungarian historiographies mostly view the relations between the Kingdom of Croatia and the Kingdom of Hungary from 1102 as a form of unequal personal union of two internally autonomous kingdoms united by a common Hungarian king.[12]

Name

The first official name of the country was "Kingdom of the Croats" (

Background

The

Kingdom

Establishment

Croatia was elevated to the status of kingdom somewhere around 925. Tomislav was the first Croatian ruler whom the papal chancellery honoured with the title "king".[17] It is generally said that Tomislav was crowned in 925, but it is not known when or by whom he was crowned, or, indeed, if he was crowned at all.[1] Tomislav is mentioned as a king in two preserved documents published in the Historia Salonitana. First in a note preceding the text of the conclusions of the Council of Split in 925, where it is written that Tomislav is the "king" ruling "in the province of the Croats and in the Dalmatian regions" (in prouintia Croatorum et Dalmatiarum finibus Tamisclao rege),[18][19][20] while in the 12th canon of the Council conclusions the ruler of the Croats is called "king" (rex et proceres Chroatorum).[20] In a letter sent by Pope John X, Tomislav is named "King of the Croats" (Tamisclao, regi Crouatorum).[18][21] The Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja titled Tomislav as a king and specified his rule at 13 years.[18] Although there are no inscriptions of Tomislav to confirm the title, later inscriptions and charters confirm that his 10th century successors called themselves "kings".[19] Under his rule, Croatia became one of the most powerful kingdoms in the Balkans.[22][23]

Tomislav, a descendant of

Croatia soon came into conflict with the Bulgarian Empire under

10th century

Croatian society underwent major changes in the 10th century. Local leaders, the župani, were replaced by the retainers of the king, who took land from the previous landowners, essentially creating a

Tomislav was succeeded by

Michael Krešimir II was succeeded by his son

11th century

As soon as Stjepan Držislav had died in 997, his three sons,

During the reign of

However, in 1072, Krešimir assisted the Bulgarian and Serb uprising against their Byzantine masters. The Byzantines retaliated in 1074 by sending the

Krešimir was succeeded by

Zvonimir's kinghood is carved in stone on the

There was no permanent

Succession crisis

The widow of the late King Zvonimir, Helen, tried to keep power in Croatia during the succession crisis.

Ladislaus died in 1095, leaving his nephew

Unification

In 1102, after the succession crisis, the crown passed into the hands of the

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations and the

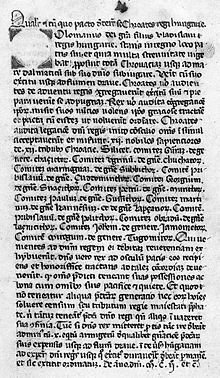

The alleged agreement called Pacta conventa (English: Agreed accords) or Qualiter (first word of the text) is today viewed as a 14th-century forgery by most modern Croatian historians. According to the document King Coloman and the twelve heads of the Croatian nobles made an agreement, in which Coloman recognised their autonomy and specific privileges. Although it is not an authentic document from 1102, nonetheless there was at least a non-written agreement that regulated the relations between Hungary and Croatia in approximately the same way,[45][52] while the content of the alleged agreement is concordant with the reality of rule in Croatia in more than one respect.[54]

The official entering of Croatia into a personal union with Hungary, later becoming part of the

Union with Hungary

In the union with Hungary, the crown was held by the

Timeline (925–1102)

See also

- Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg)

- Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia

- History of Croatia

- Pacta conventa (Croatia)

- Crown of Zvonimir

- Bans of Croatia

- Timeline of Croatian history

- List of rulers of Croatia

References

- ^ ISBN 0472081497.

- ^ "Who were Bogomils". Archived from the original on 29 May 2001. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ^ a b Larousse online encyclopedia, Histoire de la Croatie: "Liée désormais à la Hongrie par une union personnelle, la Croatie, pendant huit siècles, formera sous la couronne de saint Étienne un royaume particulier ayant son ban et sa diète." (in French)

- ^ Clifford J. Rogers: The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, Volume 1, Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 293

- ISBN 0-521-41411-3.

- ^ a b Kristó Gyula: A magyar–horvát perszonálunió kialakulása [The formation of Croatian-Hungarian personal union] Archived 31 October 2005 at the Wayback Machine(in Hungarian)

- ^ ISBN 9780719065026. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ ISBN 0415161126. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-0295800646. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-27485-2.

- ^ John Van Antwerp Fine: The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, 1991, p. 288

- ^ a b c Barna Mezey: Magyar alkotmánytörténet, Budapest, 1995, p. 66

- ^ a b Ferdo Šišić: Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara, p. 651

- ^ Monumenta spectantia historiam Slavorum meridionalium, Edidit Academia Scienciarum et Artium Slavorum Meridionalium vol VIII, Zagreb, 1877, p. 199

- ^ Lujo Margetić: Hrvatska i Crkva u srednjem vijeku, Pravnopovijesne i povijesne studije, Rijeka, 2000, p. 88-92

- ^ Lujo Margetić: Regnum Croatiae et Dalmatiae u doba Stjepana II., p. 19

- ^ Neven Budak – Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1994., p. 22

- ^ a b c Ivo Goldstein: Hrvatski rani srednji vijek, Zagreb, 1995, p. 274-275

- ^ a b c Florin Curta: Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250, Cambridge University Press. 2006, p. 196

- ^ a b Codex Diplomaticus Regni Croatiæ, Dalamatiæ et Slavoniæ, Vol I, p. 32

- ^ Codex Diplomaticus Regni Croatiæ, Dalamatiæ et Slavoniæ, Vol I, p. 34

- Yugoslavian Lexicographical Institute. 1982.

- ^ "Zoran Lukić – Hrvatska Povijest". Archived from the original on 26 September 2009.

- ^ a b John Van Antwerp Fine: The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, 1991, p. 262

- ^ De Administrando Imperio: XXXII. Of the Serbs and of the country they now dwell in

- ^ Ivo Goldstein: Hrvatski rani srednji vijek, Zagreb, 1995, p. 289-291

- ^ Clifford J. Rogers: The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, p. 162

- ^ De Administrando Imperio: 31. Of the Croats and of the country they now dwell in. "Baptized Croatia musters as many as 60 thousand horse and 100 thousand foot, and galleys up to 80 and cutters up to 100."

- ^ Vedriš, Trpimir (2007). "Povodom novog tumačenja vijesti Konstantina VII. Porfirogeneta o snazi hrvatske vojske" [On the occasion of the new interpretation of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus'report concerning the strength of the Croatian army]. Historijski zbornik (in Croatian). 60: 1–33. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ISBN 978-953-340-061-7.

- ^ Ivo Goldstein: Hrvatski rani srednji vijek, Zagreb, 1995, p. 302

- ^ John Van Antwerp Fine: The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, 1991, p. 265

- ^ Ivo Goldstein: Hrvatski rani srednji vijek, Zagreb, 1995, p. 314-315

- ^ a b Neven Budak – Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1994., p. 24-25

- ^ "festa della sensa – Veniceworld.com". Archived from the original on 1 December 2007. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ISBN 0-521-34157-4.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 279.

- ^ Curta, Florin pp. 261

- ^ Budak 1994, pp. 41–42.

- ISBN 953-214-197-9

- ISBN 978-953-169-032-4.

- ^ a b Neven Budak – Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1994., page 80 (in Croatian)

- ^ a b c d Nada Klaić: Povijest Hrvata u ranom srednjem vijeku, II Izdanje, Zagreb 1975., page 492 (in Croatian)

- ^ Pavičić, Ivana Prijatelj; Karbić, Damir (2000). "Prikazi vladarskog dostojanstva: likovi vladara u dalmatinskoj umjetnosti 13. i 14. stoljeća" [Presentation of the rulers' dignity: images of rulers in dalmatian art of the 13th and 14th centuries]. Acta Histriae (in Croatian). 8 (2): 416–418.

- ^ a b c d e f Bárány, Attila (2012). "The Expansion of the Kingdom of Hungary in the Middle Ages (1000–1490)". In Berend, Nóra. The Expansion of Central Europe in the Middle Ages. Ashgate Variorum. page 344-345

- ^ Márta Font – Ugarsko Kraljevstvo i Hrvatska u srednjem vijeku (Hungarian Kingdom and Croatia in the Middlea Ages) Archived 1 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, p. 8-9

- ^ Archdeacon Thomas of Split: History of the Bishops of Salona and Split (ch. 17.), p. 93.

- ^ Nada Klaić: Povijest Hrvata u ranom srednjem vijeku, II Izdanje, Zagreb 1975., page 508-509 (in Croatian)

- ^ ISSN 1332-4853.

- ^ Trpimir Macan: Povijest hrvatskog naroda, 1971, p. 71 (full text of Pacta conventa in Croatian)

- ^ Ferdo Šišić: Priručnik izvora hrvatske historije, Dio 1, čest 1, do god. 1107., Zagreb 1914., p. 527-528 (full text of Pacta conventa in Latin)

- ^ a b c d e "Croatia (History)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 March 2024.

- ^ Neven Budak – Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1994., page 39 (in Croatian)

- ^ a b Pál Engel: Realm of St. Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 2005, p. 35-36

- ^ "Croatia (History)". Encarta. Archived from the original on 29 June 2006.

- ^ Márta Font – Ugarsko Kraljevstvo i Hrvatska u srednjem vijeku [Hungarian Kingdom and Croatia in the Middlea Ages] Archived 1 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine "Medieval Hungary and Croatia were, in terms of public international law, allied by means of personal union created in the late 11th century."

- ^ Lukács István – A horvát irodalom története, Budapest, Nemzeti Tankönyvkiadó, 1996.[The history of Croatian literature] Archived 21 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine(in Hungarian)

- ^ ISBN 9780719065026.

- ^ Klaić, Nada (1975). Povijest Hrvata u ranom srednjem vijeku [History of the Croats in the Early Middle Ages]. p. 513.

- ^ Heka, László (October 2008). "Hrvatsko-ugarski odnosi od sredinjega vijeka do nagodbe iz 1868. s posebnim osvrtom na pitanja Slavonije" [Croatian-Hungarian relations from the Middle Ages to the Compromise of 1868, with a special survey of the Slavonian issue]. Scrinia Slavonica (in Croatian). 8 (1): 155.

- ^ Jeszenszky, Géza. "Hungary and the Break-up of Yugoslavia: A Documentary History, Part I." Hungarian Review. II (2).

- ^ Banai Miklós, Lukács Béla: Attempts for closing up by long range regulators in the Carpathian Basin

- ^ "Croatia | Encyclopedia.com". encyclopedia.com.

- ^ a b Curtis, Glenn E. (1992). "A Country Study: Yugoslavia (Former) – The Croats and Their Territories". Library of Congress. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-19-925312-8.

- ^ Desetljeće od godine 1091. do 1102. u zrcalu vrela., Mladen Ančić, Povij, pril., 17, Zagreb 1998, pp. 255

- ^ Curta, Stephenson, p. 267

- ISBN 978-0-19-533343-5.

Further reading

- Neven Budak – Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1994. (in Croatian)

- ISBN 978-0-521-81539-0.

- ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Singleton, Frederick Bernard (1985). A short history of the Yugoslav peoples. ISBN 978-0-521-27485-2.

- Curtis, Glenn E. (1992). "A Country Study: Yugoslavia (Former) – The Croats and Their Territories". Library of Congress. Retrieved 16 March 2009.