Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861)

Kingdom of Sardinia Regnum Sardiniae () | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1720–1861 | |||||||||||||||||

Coat of arms

(1833–1848) | |||||||||||||||||

| Motto: FERT (Motto for the House of Savoy) | |||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: S'hymnu sardu nationale "The Sardinian national anthem" | |||||||||||||||||

Kingdom of Sardinia in 1859 including conquest of Lombardy; client state in light green | |||||||||||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Since the Iberian period in Sardinia: Arpitan | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Catholic Church (official)[8] | ||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Sardinian | ||||||||||||||||

| Government |

| ||||||||||||||||

Victor Emmanuel II | |||||||||||||||||

Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||

• 1848 (first) | Cesare Balbo | ||||||||||||||||

• 1860–1861 (last) | Camillo Benso | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Perfect fusion | 1848 | |||||||||||||||

| 1860 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1861 | |||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||

• 1821 | 3,974,500[9] | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||

|

| History of Sardinia |

The Kingdom of Sardinia is a term used to denote the

Before becoming a possession of the House of Savoy, the medieval

Under Savoyard rule, the kingdom's government, ruling class, cultural models and center of population were entirely situated in the peninsula.

When the peninsular domains of the House of Savoy were occupied and eventually annexed by Napoleonic France, the king of Sardinia temporarily resided on the island for the first time in Sardinia's history under Savoyard rule. The Congress of Vienna (1814–15), which restructured Europe after Napoleon's defeat, returned to Savoy its peninsular possessions and augmented them with Liguria, taken from the Republic of Genoa. Following Geneva's accession to Switzerland, the Treaty of Turin (1816) transferred Carouge and adjacent areas to the newly-created Swiss Canton of Geneva. In 1847–48, through an act of Union analogous to the one between Great Britain and Ireland, the various Savoyard states were unified under one legal system with their capital in Turin, and granted a constitution, the Statuto Albertino.

By the time of the

Terminology

The Kingdom of Sardinia was the title with the highest rank among the territories possessed by the

The situation changed with the Perfect Fusion of 1847, an act of King Charles Albert of Sardinia which abolished the administrative differences between the mainland states and the island of Sardinia, creating a unitary kingdom.

History

Early history of Savoy

During the 3rd century BC, the Allobroges settled down in the region between the Rhône and the Alps. This region, named Allobrigia and later "Sapaudia" in Latin, was integrated to the Roman Empire. In the 5th century, the region of Savoy was ceded by the Western Roman Empire to the Burgundians and became part of the Kingdom of Burgundy.

In 1046,

Exchange of Sardinia for Sicily

The Spanish domination of Sardinia ended at the beginning of the 18th century, as a result of the

During the War of the Quadruple Alliance, Victor Amadeus II, Duke of Savoy and Prince of Piedmont (and now King of Sicily too), had to agree to yield Sicily to the Austrian Habsburgs and receive Sardinia in exchange. The exchange was formally ratified in the Treaty of The Hague of 17 February 1720. Because the Kingdom of Sardinia had existed since the 14th century, the exchange allowed Victor Amadeus to retain the title of king in spite of the loss of Sicily.

Victor Amadeus initially resisted the exchange, and until 1723 continued to style himself King of Sicily rather than King of Sardinia. The state took the official title of Kingdom of Sardinia, Cyprus and Jerusalem, as the House of Savoy still claimed the thrones of Cyprus and Jerusalem, although both had long been under Ottoman rule.

In 1767–1769,

Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna

In 1792, the Kingdom of Sardinia and the other states of the Savoy crown joined the

The refusal by the Savoyards of recognizing the Sardinian's rights and representaion in government[24][25][26] caused the Sardinian Vespers (also known as the "Three years of revolution") started by sa dii de s'aciappa[27] ("the day of the pursuit and capture"), commemorated today as Sa die de sa Sardigna, when people in Cagliari started chasing any Piedmontese functionaries they could find and expelled them from the island. Thus, Sardinia became the first European country to have engaged in a revolution of its own, the episode not being the result of a foreign military importation like in most of Europe.[28]

In 1814, the Crown of Savoy enlarged its territories with the addition of the former

In the reaction after Napoleon, the country was ruled by conservative monarchs:

The Kingdom of Sardinia industrialized from 1830 onward. A constitution, the

Savoyard struggle for the Italian unification

Like all the various

In 1852, a liberal ministry under

In 1859, France sided with the Kingdom of Sardinia in a war against

Due to the Austrian government's refusal to cede any lands to the Kingdom of Sardinia, they agreed to cede Lombardy to Napoleon, who in turn then ceded the territory to the Kingdom of Sardinia to avoid "embarrassing" the defeated Austrians. Cavour angrily resigned from office when it became clear that Victor Emmanuel would accept this arrangement.

Garibaldi and the Thousand

On 5 March 1860,

In 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi started his campaign to conquer southern Italy in the name of the Kingdom of Sardinia. He quickly toppled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which was the largest of the states in the region, stretching from Abruzzo and Naples on the peninsula to Messina and Palermo on Sicily. He then marched to Gaeta in the central peninsula. Cavour was satisfied with the unification, while Garibaldi, who was too revolutionary for the king and his prime minister, wanted to conquer Rome as well.

Garibaldi was disappointed in this development, as well as in the loss of his home province, Nice, to France. He also failed to fulfill the promises that had gained him popular and military support by the Sicilians: that the new nation would be a republic, not a kingdom, and that the Sicilians would see great economic gains after unification. The former did not come to pass until 1946.

Towards the Kingdom of Italy

On 17 March 1861, law no. 4671 of the

Economy

Major progress in the economy was achieved during the government of

Currency

The currency in use in Savoy was the Piedmontese scudo. During the Napoleonic era, it was replaced in general circulation by the French franc. In 1816, after regaining their peninsular domains, the scudo was replaced by the Sardinian lira, which in 1821 also replaced the Sardinian scudo, the coins that had been in use on the island throughout the period.

Government

Before 1847, only the island of Sardinia proper was part of the

The Perfect Fusion (Fusione perfetta) was the 1847 act of the Savoyard King Charles Albert of Sardinia which abolished the administrative differences between the mainland states and the island of Sardinia, in a fashion similar to the Nueva Planta decrees between the Crown of Castile and the realms of the Crown of Aragon between 1707 and 1716 and the Acts of Union between Great Britain and Ireland in 1800.

In 1848, King Charles Albert granted the

The head of state was the King of Sardinia, while the head of the government was the Prime minister of the Kingdom of Sardinia.

Military

The Royal Sardinian Army and the Royal Sardinian Navy functioned as the military of Kingdom of Sardinia until they became the Royal Italian Army on 4 May 1861 and the Regia Marina on 17 March 1861.

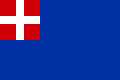

Flags, royal standards and coats of arms

When the Duchy of Savoy acquired the

Eventually, King

- Coats of arms

-

(1720–1815)

-

(1815–1831)

-

(1831–1848)

-

(1848–1861)

- State Flags

-

Royal Standard of the Savoyard kings of Sardinia of Savoy dynasty (1720-1848) and State Flag of the Savoyard States (late 16th - late 18th century)

-

State Flag and War Ensign (1816–1848): Civil Flag "crowned"

-

State and war flag (1848–1851)

-

State flag and war ensign (1851–1861)

- Other Flags

-

Merchant Flag

(c.1799–1802) -

War Ensign of the Royal Sardinian Navy (1785–1802)

-

Merchant Flag

(1802–1814) -

War Ensign

(1802–1814) -

Merchant Flag and War Ensign (1814–1816)

-

Civil Flag and Civil Ensign (1816–1848)

-

War Ensign of the Kingdom of Sardinia (1816–1848) aspect ratio 31:76

-

Civil and merchant flag (1851–1861), the Italian tricolore with the coat of arms of Savoy as an inescutcheon

- Royal Standards

-

(1848–1861) and Kingdom of Italy (1861–1880)

-

Crown Prince (1848–1861) and Crown Prince of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1880)

Maps

Territorial evolution of the Kingdom of Sardinia from 1859 to 1860

-

1859:Kingdom of Sardinia

-

1860:Kingdom of Sardinia

After the annexation of Lombardy and before the annexation of the United Provinces of Central Italy -

1861:Kingdom of Sardinia

After the Expedition of the Thousand, and on the eve of the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy.

See also

- List of monarchs of Sardinia

- List of viceroys of Sardinia

- Spanish Empire

- S'hymnu sardu nationale

- Kingdom of Sardinia (1324–1720)

- Kingdom of Sardinia (1700–1720)

Notes and references

Footnotes

Notes

- ^ a b "Bandiere degli Stati preunitari italiani: Sardegna.". Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Flags of the World: Kingdom of Sardinia – Part 2 (Italy).". Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Storia della lingua sarda, vol. 3, a cura di Giorgia Ingrassia e Eduardo Blasco Ferrer

- ^ The phonology of Campidanian Sardinian : a unitary account of a self-organizing structure, Roberto Bolognesi, The Hague : Holland Academic Graphics

- ^ S'italianu in Sardìnnia, Amos Cardia, Iskra

- ^ Settecento sardo e cultura europea: Lumi, società, istituzioni nella crisi dell'Antico Regime; Antonello Mattone, Piero Sanna; FrancoAngeli Storia; pp.18

- ^ "Limba Sarda 2.0S'italianu in Sardigna? Impostu a òbligu de lege cun Boginu – Limba Sarda 2.0". Limba Sarda 2.0. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-3-643-99894-1.

In 1848, the Statute or constitution issued by King Carlo Alberto for the kingdom of Sardinia proclaimed "the only State religion" the Roman Catholic one.

- ISBN 978-1-341-37795-2. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-511-52329-8, archivedfrom the original on 2023-05-10, retrieved 2023-05-10

- JSTOR 10.5325/j.ctv1c9hnc2.

- ISBN 978-0-271-09100-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-08-16. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ISBN 978-1-350-15219-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-08-16. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- ^ "Sardinia-Piedmont, Kingdom of, 1848–1849". www.ohio.edu. Archived from the original on 2023-01-19. Retrieved 2023-01-19.

- ISBN 978-1-315-83683-6. Archived from the original on 2023-01-19. Retrieved 2023-01-19.)

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help - ISBN 978-0-19-995106-2.

- ^ "Sardinia, Historical Kingdom". Archived from the original on 2023-06-05. Retrieved 2023-01-19., Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Aldo Sandulli; Giulio Vesperini (2011). "L'organizzazione dello Stato unitario" (PDF). Rivista trimestrale di diritto pubblico (in Italian): 47–49. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-350-15219-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-08-16. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- ISBN 978-0-271-09100-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-08-16. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-271-09100-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-08-16. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-139-42519-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-08-16. Retrieved 2023-05-18.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-107-14770-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-08-16. Retrieved 2023-05-18.

- ^ "The resentment of the Sardinian Nation towards the Piedmontese had been growing for more than half a century, when they [Piedmontese] began to keep for themselves all the lucrative employments on the island, to violate the ancient privileges granted to the Sardinians by the Kings of Aragon, to promote to the highest positions people of their own kind while leaving to the Sardinians only the episcopates of Ales, Bosa and Castelsardo, that is Ampurias. The arrongance and scorn with which the Piedmontese had been treating the Sardinians by calling them bums, dirty, cowards and other similar and irritating names, and above all the most common expression of Sardi molenti, that is "Sardinian donkeys", did little but worsen their disposition as the days passed, and gradually alienated them from this nation." Tommaso Napoli, Relazione ragionata della sollevazione di Cagliari e del Regno di Sardegna contro i Piemontesi

- ^ "The hostility against the Piedmontese was no longer a matter of employments, like the last period of Spanish rule, the dispatches of the viceroy Balbiano and the demands of the Stamenti may paint it out to be. The Sardinians wanted to get rid of them not only because they stood as a symbol of an anachronistic dominion, hostile to both the autonomy and the progress of the island, but also and perhaps especially because their presumptuosness and intrusiveness had already become insufferable." Raimondo Carta Raspi, Storia della Sardegna, Editore Mursia, Milano, 1971, pp.793

- ^ "Che qualcosa bollisse in pentola, in Sardegna, poteva essere compreso fin dal 1780. Molte delle recriminazioni contro il governo piemontese erano ormai più che mature, con una casistica di atti, fatti, circostanze a sostenerle, tanto per la classe aristocratica, quanto per le altre componenti sociali." Onnis, Omar (2015). La Sardegna e i sardi nel tempo, Arkadia, Cagliari, p.149

- ^ Sa dì de s´acciappa – Dramma storico in due tempi e sette quadri Archived 2018-06-25 at the Wayback Machine, Piero Marcialis, 1996, Condaghes

- ^ "Mentre a Parigi si ghigliottinava Robespierre e il governo repubblicano prendeva una piega più moderata, la Sardegna era in piena rivoluzione. Primo paese europeo a seguire l'esempio della Francia, peraltro dopo averne respinto le avance militari. La rivoluzione in Sardegna, insomma, non era un fenomeno d'importazione. [...] Le rivoluzioni altrove furono suscitate dall'arrivo delle armi francesi e da esse protette (come la rivoluzione napoletana del 1799). È un tratto peculiare, quasi sempre trascurato, della nostra stagione rivoluzionaria." Onnis, Omar (2015). La Sardegna e i sardi nel tempo, Arkadia, Cagliari, p.152

- ^ Wells, H. G., Raymond Postgate, and G. P. Wells. The Outline of History, Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1956. p. 753

- ^ Wambaugh, Sarah & Scott, James Brown (1920), A Monograph on Plebiscites, with a Collection of Official Documents, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 599

- ISBN 978-0-7190-6996-3. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ "Coppa, Frank J., "Cavour, Count Camillo Benso di (1810–1861)", Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions, Ohio University, 1998". Archived from the original on 2010-06-09. Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- ^ Beales & Biagini, The Risorgimento and the Unification of Italy, p. 108.

- ^ "Flags of the World: Kingdom of Sardinia – Part 1 (Italy).". Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

Bibliography

- Antonicelli, Aldo. "From Galleys to Square Riggers: The modernization of the navy of the Kingdom of Sardinia." The Mariner's Mirror 102.2 (2016): 153–173 online[dead link].

- Hearder, Harry (1986). Italy in the Age of the Risorgimento, 1790–1870. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-49146-0.

- Luttwak Edward, The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire, The Belknap Press, 2009, ISBN 9780674035195

- Martin, George Whitney (1969). The Red Shirt and the Cross of Savoy. New York: Dodd, Mead and Co. ISBN 0-396-05908-2.

- Murtaugh, Frank M. (1991). Cavour and the Economic Modernization of the Kingdom of Sardinia. New York: Garland Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-0-8153-0671-9.

- Romani, Roberto. "The Reason of the Elites: Constitutional Moderatism in the Kingdom of Sardinia, 1849–1861." in Sensibilities of the Risorgimento (Brill, 2018) pp. 192–244.

- Romani, Roberto. "Reluctant Revolutionaries: Moderate Liberalism in the Kingdom of Sardinia, 1849–1859." Historical Journal (2012): 45–73. online

- Schena, Olivetta. "The role played by towns in parliamentary commissions in the kingdom of Sardinia in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries." Parliaments, Estates and Representation 39.3 (2019): 304–315.

- Smith, Denis Mack. Victor Emanuel, Cavour and the Risorgimento (Oxford UP, 1971) online.

- Storrs, Christopher (1999). War, Diplomacy and the Rise of Savoy, 1690–1720. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55146-3.

- Thayer, William Roscoe (1911). The Life and Times of Cavour vol 1. old interpretations but useful on details; vol 1 goes to 1859]; volume 2 online covers 1859–62

In Italian

- AAVV. (a cura di F. Manconi), La società sarda in età spagnola, Cagliari, Consiglio Regionale della Sardegna, 2 voll., 1992-3

- Blasco Ferrer Eduardo, Crestomazia Sarda dei primi secoli, collana Officina Linguistica, Ilisso, Nuoro, 2003, ISBN 9788887825657

- Boscolo Alberto, La Sardegna bizantina e alto giudicale, Edizioni Della TorreCagliari 1978

- ISBN 8871380843

- Coroneo Roberto, Arte in Sardegna dal IV alla metà dell'XI secolo, edizioni AV, Cagliari, 2011

- Coroneo Roberto, Scultura mediobizantina in Sardegna, Nuoro, Poliedro, 2000,

- Gallinari Luciano, Il Giudicato di Cagliari tra XI e XIII secolo. Proposte di interpretazioni istituzionali, in Rivista dell'Istituto di Storia dell'Europa Mediterranea, n°5, 2010

- Manconi Francesco, La Sardegna al tempo degli Asburgo, Il Maestrale, Nuoro, 2010, ISBN 9788864290102

- Manconi Francesco, Una piccola provincia di un grande impero, CUEC, Cagliari, 2012, ISBN 8884677882

- Mastino Attilio, Storia della Sardegna Antica, Il Maestrale, Nuoro, 2005, ISBN 9788889801635

- Meloni Piero, La Sardegna Romana, Chiarella, Sassari, 1980

- Motzo Bachisio Raimondo, Studi sui bizantini in Sardegna e sull'agiografia sarda, Deputazione di Storia Patria della Sardegna, Cagliari, 1987

- Ortu Gian Giacomo, La Sardegna dei Giudici, Il Maestrale, Nuoro, 2005, ISBN 9788889801024

- Paulis Giulio, Lingua e cultura nella Sardegna bizantina: testimonianze linguistiche dell'influsso greco, Sassari, L'Asfodelo, 1983

- Spanu Luigi, Cagliari nel seicento, Edizioni Castello, Cagliari, 1999

- Zedda Corrado – Pinna Raimondo, La nascita dei Giudicati. Proposta per lo scioglimento di un enigma storiografico, in Archivio Storico Giuridico di Sassari, seconda serie, n° 12, 2007