Koala

| Koala Temporal range: Middle Pleistocene – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Phascolarctidae |

| Genus: | Phascolarctos |

| Species: | P. cinereus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Phascolarctos cinereus (Goldfuss, 1817)

| |

| |

| Koala range

Native

Introduced

| |

| Synonyms[2]: 45 [3] | |

The koala (Phascolarctos cinereus), sometimes called the koala bear, is an

Koalas typically inhabit open

Because of their distinctive appearance, koalas, along with

Etymology

The word "koala" comes from the

Adopted by white settlers, "koala" became one of several hundred Aboriginal loan words in Australian English, where it was also commonly referred to as "native bear",[5] later "koala bear", for its supposed resemblance to a bear.[6] It is also one of several Aboriginal words that made it into International English alongside words like "didgeridoo" and "kangaroo".[6] The generic name, Phascolarctos, is derived from the Greek words φάσκωλος (phaskolos) 'pouch' and ἄρκτος (arktos) 'bear'. The specific name, cinereus, is Latin for 'ash coloured'.[7]

Taxonomy

The koala was given its generic name Phascolarctos in 1816 by French zoologist

Evolution

The koala is classified with wombats (family Vombatidae) and several extinct families (including marsupial tapirs, marsupial lions and giant wombats) in the suborder Vombatiformes within the order Diprotodontia.[10] The Vombatiformes are a sister group to a clade that includes macropods (kangaroos and wallabies) and possums.[11] The koala's lineage possibly branched off around 40 million years ago during the Eocene.[12]

The modern koala is the only

: 226P. cinereus may have emerged as a dwarf form of the giant koala (P. stirtoni), following the disappearance of several giant animals in the late Pleistocene. A 2008 study questions this hypothesis, noting that P. cinereus and P. stirtoni were sympatric during the middle to late Pleistocene, and the major difference in the morphology of their teeth.[17] The fossil record of the modern koala extends back at least to the middle Pleistocene.[18]

| Molecular relationship between living Diprotodontia families based on Phillips and collages (2023)[19] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Morphology tree of Phascolarctidae based on Beck and collages (2020)[20] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Genetics and variations

Three

Other studies have found that koala populations have high levels of inbreeding and low genetic variation.[23][24] Such low genetic diversity may have been caused by declines in the population during the late Pleistocene.[25] Rivers and roads have been shown to limit gene flow and contribute to the isolation of southeast Queensland populations.[26] In April 2013, scientists from the Australian Museum and Queensland University of Technology announced they had fully sequenced the koala genome.[27]

Characteristics

The koala is a robust animal with a large head and vestigial or non-existent tail.[9]: 1 [28] It has a body length of 60–85 cm (24–33 in) and a weight of 4–15 kg (9–33 lb),[28] making it among the largest arboreal marsupials.[29] Koalas from Victoria are twice as heavy as those from Queensland.[21]: 7 The species is sexually dimorphic, with males 50% larger than females. Males are further distinguished from females by their more curved noses[29] and the presence of chest glands, which are visible as bald patches.[21]: 55 The female's pouch opening is secured by a sphincter which holds the young in.[30]

The pelage of the koala is denser on the back.

For a mammal, the koala has a

The koala has a broad, dark nose

The koala has several adaptations for its poor, toxic and fibrous diet.

Koalas are

Distribution and habitat

The koala's geographic range covers roughly 1,000,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi), and 30 ecoregions.[39] It ranges throughout mainland eastern and southeastern Australia, including the states of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia. The koala was also introduced to several nearby islands.[1] The population on Magnetic Island represents the northern limit of its range.[39]

Fossil evidence shows that the koala's range stretched as far west as southwestern

Behaviour and ecology

Foraging and activities

Koalas are

Due to their low-energy diet, koalas limit their activity and sleep 20 hours a day.[9]: 93 [44] They are predominantly active at night and spend most of their waking hours foraging. They typically eat and sleep in the same tree, possibly for as long as a day.[21]: 39 On warm days, a koala may rest with its back against a branch or lie down with its limbs dangling.[9]: 93–94 When it gets very hot, the koala rests lower in the canopy and near the trunk, where the surface is cooler than the surrounding air.[45] It curls up when it gets cold and wet.[21]: 39 A koala will find a lower, thicker branch on which to rest when it gets windy. While it spends most of the time in the tree, the animal descends to the ground to move to another tree, with either a walking or leaping gait.[9]: 93–94 The koala usually grooms itself with its hind paws, with their double claws, but sometimes uses its forepaws or mouth.[9]: 97–98

Social life

Koalas are asocial animals and spend just 15 minutes a day on social behaviours. Where there are more koalas and fewer trees,

Adult males communicate with loud bellows — "a long series of deep, snoring inhalations and belching exhalations".[49] Because of their low frequency, these bellows can travel far through the forest.[21]: 56 Koalas may bellow at any time of the year, particularly during the breeding season, when it serves to attract females and possibly intimidate other males.[50] They also bellow to advertise their presence to their neighbours when they climb a different tree.[21]: 57 These sounds signal the male's actual body size, as well as exaggerate it;[51] females pay more attention to bellows that originate from larger males.[52] Female koalas bellow, though more softly, in addition to making snarls, wails, and screams. These calls are produced when in distress and when making defensive threats.[49] Squeaking and sqawking are produced when distraught; the former is made by younger animals and the latter by older ones. When another individual climbs over it, a koala makes a low closed-mouth grunt.[9]: 102–03 [49] Koalas also communicate with facial expressions. When snarling, wailing, or squawking, the animal curls the upper lip and points its ears forward. Screaming koalas pull their lips and ears back. Females form an oval shape with their lips when annoyed.[9]: 104–05

Agonistic behaviour typically consists of quarrels between individuals that are trying to pass each other in the tree. This occasionally involves biting. Strangers may wrestle, chase, and bite each other.[9]: 102 [53] In extreme situations, a male may try to displace a smaller rival from a tree, chasing, cornering and biting it. Once the individual is driven away, the victor bellows and marks the tree.[9]: 101–02 Pregnant and lactating females are particularly aggressive and attack individuals that come too close.[53] In general, however, koalas tend to avoid fighting due to energy costs.[2]: 191

Reproduction and development

Koalas are seasonal breeders, and give birth from October to May. Females in

Koalas are

The joey latches on to one of the female's two teats and suckles it.[21]: 61 The female lactates for as long as a year to make up for her low energy production. Unlike in other marsupials, koala milk becomes less fatty as the joey grows in the pouch.[21]: 62 After seven weeks, the joey has a proportionally large head, clear edges around its face, more colouration, and a visible pouch (if female) or scrotum (male). At 13 weeks, the joey weighs around 50 g (1.8 oz) and its head is twice as big as before. The eyes begin to open and hair begins to appear. At 26 weeks, the fully furred animal resembles an adult and can look outside the pouch.[21]: 63

At six or seven months of age, the joey weighs 300–500 g (11–18 oz) and fully emerges from the pouch for the first time. It explores its new surroundings cautiously, clutching its mother for support.[21]: 65 Around this time, the mother prepares it for a eucalyptus diet by producing a faecal pap that the joey eats from her cloaca. This pap comes from the cecum, is more liquid than regular faeces, and is filled with bacteria.[56] A nine month old joey has its adult coat colour and weighs 1 kg (2.2 lb). Having permanently left the pouch, it rides on its mother's back for transportation, learning to climb by grasping branches.[21]: 65–66 Gradually, it becomes more independent from its mother, who becomes pregnant again after a year, and the young is now around 2.5 kg (5.5 lb). Her bond with her previous offspring is permanently severed and she no longer allows it to suckle, but it will stay nearby until it is one-and-a-half to two years old.[21]: 66–67

Females become sexually mature at about three years of age and can then become pregnant; in comparison, males reach sexual maturity when they are about four years old,[57] although they can experience spermatogenesis as early as two years.[21]: 68 Males do not start marking their scent until they reach sexual maturity, though their chest glands become functional much earlier.[48] Koalas can breed every year if environmental conditions are good, though the long dependence of the young usually leads to year-long gaps in births.[16]: 236

Health and mortality

Koalas may live from 13 to 18 years in the wild. While female koalas usually live this long, males may die sooner because of their more risky lives.

Koalas can be subject to

The animals are vulnerable to

Human relations

History

The first written reference to the koala was recorded by John Price, servant of

Botanist

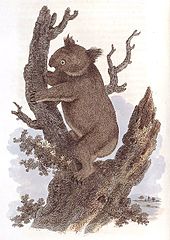

George Perry would officially publish the first image of the koala in his 1810 natural history work Arcana.[2]: 37 Perry called it the "New Holland Sloth", and his dislike for the koala, evident in his description of the animal, was reflected in the contemporary British attitudes towards Australian animals as strange and primitive:[2]: 40

... the eye is placed like that of the Sloth, very close to the mouth and nose, which gives it a clumsy awkward appearance, and void of elegance in the combination ... they have little either in their character or appearance to interest the Naturalist or Philosopher. As Nature however provides nothing in vain, we may suppose that even these torpid, senseless creatures are wisely intended to fill up one of the great links of the chain of animated nature ...[65]

Naturalist and popular artist John Gould illustrated and described the koala in his three-volume work The Mammals of Australia (1845–1863) and introduced the species, as well as other members of Australia's little-known faunal community, to the public.[2]: 87–93 Comparative anatomist Richard Owen, in a series of publications on the physiology and anatomy of Australian mammals, presented a paper on the anatomy of the koala to the Zoological Society of London.[66] In this widely cited publication, he provided an early description of its internal anatomy, and noted its general structural similarity to the wombat.[2]: 94–96 English naturalist George Robert Waterhouse, curator of the Zoological Society of London, was the first to correctly classify the koala as a marsupial in the 1840s, and compared it to fossil species Diprotodon and Nototherium, which had been discovered just recently.[2]: 46–48 Similarly, Gerard Krefft, curator of the Australian Museum in Sydney, noted evolutionary mechanisms at work when comparing the koala to fossil marsupials in his 1871 The Mammals of Australia.[2]: 103–105

Britain finally received a living koala in 1881, which was obtained by the Zoological Society of London. As related by prosecutor to the society, William Alexander Forbes, the animal suffered an accidental demise when the heavy lid of a washstand fell on it and it was unable to free itself. Forbes dissected the fresh specimen and wrote about the female reproductive system, the brain, and the liver — parts not previously described by Owen, who had access only to preserved specimens.[2]: 105–06 Scottish embryologist William Caldwell — well known in scientific circles for determining the reproductive mechanism of the platypus — described the uterine development of the koala in 1884,[67] and used this new information to convincingly map out the evolutionary timeline of the koala and the monotremes.[2]: 111

Cultural significance

The koala is well known worldwide and is a major draw for Australian zoos and wildlife parks. It has been featured in popular culture and as

The koala is featured in the

Early European settlers in Australia considered the koala to be a creeping

The song "Ode to a Koala Bear" appears on the

Koala diplomacy

Several political leaders and members of royal families had their pictures taken with koalas, including

Conservation

The koala was originally classified as Least Concern on the Red List, and reassessed as Vulnerable in 2014.[1] In the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales and Queensland, the species was listed under the EPBC Act in February 2022 as endangered by extinction.[75][76] The described population was determined in 2012 to be "a species for the purposes of the EPBC Act 1999" in Federal legislation.[77]

Australian policymakers had declined a 2009 proposal to include the koala in the

The koala was heavily hunted by European settlers in the early 20th century,[2]: 121–128 largely for its fur. Australia exported as many as two million pelts by 1924. Koala furs were used to make rugs, coat linings, muffs, and on women's garment trimmings.[2]: 125 The first successful efforts at conserving the species were initiated by the establishment of Brisbane's Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary and Sydney's Koala Park Sanctuary in the 1920s and 1930s. The owner of the latter park, Noel Burnet, created the first successful breeding program and earned a reputation as a top expert on the species.[2]: 157–159

One of the biggest anthropogenic threats to the koala is habitat destruction and fragmentation. Near the coast, the main cause of this is urbanisation, while in rural areas, habitat is cleared for agriculture. Its favoured trees are also taken down to be made into wood products.[21]: 104–107 In 2000, Australia had the fifth highest rate of land clearance globally, having removed 564,800 hectares (1,396,000 acres) of native plants.[9]: 222 The distribution of the koala has shrunk by more than 50% since European arrival, largely due to fragmentation of habitat in Queensland.[39] Nevertheless, koalas live in many protected areas.[1]

While urbanisation can pose a threat to koala populations, the animals can survive in urban areas provided enough trees are present.

See also

- Drop bear - A predatory and dangerous version of the koala in popular folklore

- Fauna of Australia

- List of monotremes and marsupials of Australia

- Sam (koala), a female koala known for being rescued during the Black Saturday bushfires in 2009

References

- ^ . Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- OCLC 62265494.

- ISBN 978-0-19-554073-4.

- ^ Edward E. Morris (1898). Dictionary of Australian Words (orig) Austral English. This author strongly deprecated use of another synonym, "sloth".

- ^ .

Dixon et al. (1990) believe there to be some 400 loans in Mainstream Australian English [...] Some Aboriginal expressions have entered the stock of world English vocabulary; witness kangaroo, didgeridoo, koala, [...] Sometimes popular usage deviated markedly from scientific taxonomies, as in the case of the koala which became known as koala bear. [...] Both mallee and mallee scrub, koala, and koala bear are common today.

- ISBN 978-0-00-458641-0.

- ^ de Blainville, H. (1816). "Prodrome d'une nouvelle distribution systématique du règne animal". Bulletin de la Société Philomáthique, Paris (in French). 8: 105–24. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-74237-323-2. Archivedfrom the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8018-7223-5.

- PMID 15324852.

- .

- ^ S2CID 86356713.

- doi:10.1071/AM99001. Archivedfrom the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- S2CID 86152273.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-643-06257-3. Archivedfrom the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-642-25037-8.

- S2CID 257634430.

- PMID 32587406.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-57524-136-4. Archivedfrom the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ S2CID 36771770.

- S2CID 22441918.

- .

- PMID 23095716.

- S2CID 36855057.

- ^ Davey, M. (10 April 2013). "Australians crack the code of koala's genetic blueprint". The Age. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-8211-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-643-06635-9.

- .

- S2CID 31042136.

- doi:10.1071/AM98315. Archivedfrom the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ ISBN 9781324036845.

- S2CID 3708255.

- PMID 24309276.

- ISBN 978-0-86840-354-0.

- .

- PMID 29967444.

- ^ PMID 23527258.

- ^ "Species Phascolarctos cinereus (Goldfuss, 1817)". Australian Faunal Directory. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- S2CID 8031502.

- ISBN 978-0-7607-1969-5.

- from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- S2CID 11662113.

- PMID 24899683.

- doi:10.1071/WR01042.

- .

- ^ doi:10.1071/ZO08090.

- ^ .

- .

- PMID 21957105.

- S2CID 53175246.

- ^ .

- PMID 15509709.

- PMID 11943495.

- .

- S2CID 26046352.

- ISSN 0952-8369.

- S2CID 26037401.

- PMID 21524321.

- PMID 17118218.

- doi:10.1071/WR10156.

- OCLC 21532917.

- from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ Perry, G. (1811). "Koalo, or New Holland Sloth". Arcana; or the Museum of Natural History: 109. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ Caldwell, H. (1884). "On the arrangement of the embryonic membranes in marsupial mammals". Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. s2–24 (96): 655–658. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ Donnison, Jon (16 November 2014). "G20 summit: Koalas and 'shirtfronting'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ Dimitrova, Kami (16 November 2014). "President Obama, Putin Cozy Up With Koalas at G20 Summit" Archived 3 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine. ABC News. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ Harris Rimmer, Susan (18 November 2014). "Koala diplomacy: Australian soft power saves the day at G20" Archived 27 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Conversation. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ Arup, Tom (26 December 2014). "The rise and influence of koala diplomacy" Archived 17 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "Oxford Word of the Month – December: koala diplomacy" Archived 17 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Oxford University Press, 28 November 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "Koala diplomacy as furry envoys return to Australia" Archived 13 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Media release, Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 10 February 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ Markwell, Kevin & Cushing, Nancy (20 May 2015). "Koalas, platypuses and pandas and the power of soft diplomacy" Archived 5 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Conversation. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "Phascolarctos cinereus (combined populations of Qld, NSW and the ACT) — Koala (combined populations of Queensland, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory)". SPRAT. Australian Government. 2022. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Cox, Lisa (11 February 2022). "Koala listed as endangered after Australian governments fail to halt its decline". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Burke, Tony (27 April 2012). "Determination that a distinct population of biological entities is a species for the purposes of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (132)". Australian Government - Federal Register of Legislation. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Christine Adams-Hosking (May 2017). Current status of the koala in Queensland and New South Wales (Report). WWF Australia. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Koalas added to threatened species list". ABC. 30 April 2012. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Koala declared endangered as disease, lost habitat take toll". AP News. 11 February 2022. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Buchholz, Katharina (27 November 2019). "Infographic: The Worrying Decline of Koala Populations". Statista Infographics. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) Fact Sheet: Population & Conservation Status". San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. June 2021. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Australia warns koalas 'endangered' as numbers plunge". Phys.org. 11 February 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ a b Holtcamp, W. (5 January 2007). "Will Urban Sprawl KO the Koala?". National Wildlife. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "Cars and dogs threaten koala future". University of Queensland News. 14 February 2006. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Foden, W.; Stuart, S. N. (2009). Species and Climate Change: More than Just the Polar Bear (PDF) (Report). IUCN Species Survival Commission. pp. 36–37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-922431-20-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.)

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help - ^ "Koalas and resilient habitat in the Sutherland Shire". Sutherland Shire Environment Centre. September 2021. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Moore, Tony (26 July 2016). "Koalas tunnels and bridges prove effective on busy roads". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Clever koalas learn to cross the road safely". BBC News. 27 July 2016. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

External links

- Arkive – images and movies of the koala Phascolarctos cinereus

- Animal Diversity Web – Phascolarctos cinereus

- iNaturalist crowdsourced koala sighting photos (mapped, graphed)

- Koala Science Community Archived 5 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- "Koala Crunch Time" – an ABC documentary (2012)

- "Koalas deserve full protection"

- Cracking the Koala Code – a PBS Naturedocumentary (2012)

- The Aussie Koala Ark Conservation Project Archived 12 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine