Kurds

Gorani[32] | |

| Religion | |

|---|---|

| Predominantly Sunni Islam with minorities of Shia Islam, Kurdish Alevism, Yazidism, Yarsanism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Christianity[33][34][35] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Iranic peoples |

|

Kurdish people or Kurds (

Kurds speak the

Kurds do not comprise a majority in any country, making them a stateless people.

Etymology

The exact origins of the name Kurd are unclear.

There are, however, dissenting views, which do not derive the name of the Kurds from Qardu and Corduene but opt for derivation from Cyrtii (Cyrtaei) instead.[48]

Regardless of its possible roots in ancient toponymy, the ethnonym Kurd might be derived from a term kwrt- used in Middle Persian as a common noun to refer to "nomads" or "tent-dwellers," which could be applied as an attribute to any Iranian group with such a lifestyle.[49]

The term gained the characteristic of an ethnonym following the Muslim conquest of Persia, as it was adopted into Arabic and gradually became associated with an amalgamation of Iranian and Iranianized tribes and groups in the region.[50][51]

Language

Kurdish (Kurdish: Kurdî or کوردی) is a collection of related dialects spoken by the Kurds.[52] It is mainly spoken in those parts of Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey which comprise Kurdistan.[53] Kurdish holds official status in Iraq as a national language alongside Arabic, is recognized in Iran as a regional language, and in Armenia as a minority language. The Kurds are recognized as a people with a distinct language by Arab geographers such as Al-Masudi since the 10th century.[54]

Many Kurds are either

According to Mackenzie, there are few linguistic features that all Kurdish dialects have in common and that are not at the same time found in other Iranian languages.[55]

The Kurdish dialects according to Mackenzie are classified as:[56]

- Northern group (the Kurmanji dialect group)

- Central group (part of the Sorani dialect group)

- Southern group (part of the Xwarin dialect group) including Laki

The Zaza and Gorani are ethnic Kurds,[57] but the Zaza–Gorani languages are not classified as Kurdish.[58]

Population

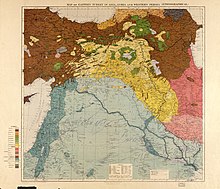

The number of Kurds living in

The total number of Kurds in 1991 was placed at 22.5 million, with 48% of this number living in Turkey, 24% in Iran, 18% in Iraq, and 4% in Syria.[61]

Recent emigration accounts for a population of close to 1.5 million in Western countries, about half of them in Germany.

A special case are the Kurdish populations in the

Religion

Islam

Most Kurds are

Beside Sunni Islam, Alevism and Shia Islam also have millions of Kurdish followers.[66]

Yazidism

Yazidism is a

Yarsanism

Yarsanism (also known as Ahl-I-Haqq, Ahl-e-Hagh or Kakai) is also one of the religions that are associated with Kurdistan.

Although most of the sacred Yarsan texts are in the

Zoroastrianism

The Iranian religion of Zoroastrianism has had a major influence on the Iranian culture, which Kurds are a part of, and has maintained some effect since the demise of the religion in the Middle Ages. The Iranian philosopher Sohrevardi drew heavily from Zoroastrian teachings.[79] Ascribed to the teachings of the prophet Zoroaster, the faith's Supreme Being is Ahura Mazda. Leading characteristics, such as messianism, the Golden Rule, heaven and hell, and free will influenced other religious systems, including Second Temple Judaism, Gnosticism, Christianity, and Islam.[80]

In 2016, the first official Zoroastrian fire temple of Iraqi Kurdistan opened in Sulaymaniyah. Attendees celebrated the occasion by lighting a ritual fire and beating the frame drum or 'daf'.[81] Awat Tayib, the chief of followers of Zoroastrianism in the Kurdistan region, claimed that many were returning to Zoroastrianism but some kept it secret out of fear of reprisals from Islamists.[81]

Christianity

Although historically there have been various accounts of

Segments of the Bible were first made available in the Kurdish language in 1856 in the Kurmanji dialect. The Gospels were translated by Stepan, an Armenian employee of the

History

Antiquity

"The land of Karda" is mentioned on a Sumerian clay tablet dated to the 3rd millennium BC. This land was inhabited by "the people of Su" who dwelt in the southern regions of Lake Van; the philological connection between "Kurd" and "Karda" is uncertain, but the relationship is considered possible.[90] Other Sumerian clay tablets referred to the people, who lived in the land of Karda, as the Qarduchi (Karduchi, Karduchoi) and the Qurti.[91] Karda/Qardu is etymologically related to the Assyrian term Urartu and the Hebrew term Ararat.[92] However, some modern scholars do not believe that the Qarduchi are connected to Kurds.[93][94]

Qarti or Qartas, who were originally settled on the mountains north of Mesopotamia, are considered as a probable ancestor of the Kurds. The Akkadians were attacked by nomads coming through Qartas territory at the end of 3rd millennium BC and distinguished them as the Guti, speakers of a pre-Iranic language isolate. They conquered Mesopotamia in 2150 BC and ruled with 21 kings until defeated by the Sumerian king Utu-hengal.[95]

Many Kurds consider themselves descended from the

During the

You've bitten off more than you can chew

and you have brought death to yourself.

O son of a Kurd, raised in the tents of the Kurds,

who gave you permission to put a crown on your head?[109]

The usage of the term Kurd during this time period most likely was a social term, designating Northwestern Iranian nomads, rather than a concrete ethnic group.[109][110]

Similarly, in AD 360, the Sassanid king Shapur II marched into the Roman province Zabdicene, to conquer its chief city, Bezabde, present-day Cizre. He found it heavily fortified, and guarded by three legions and a large body of Kurdish archers.[111] After a long and hard-fought siege, Shapur II breached the walls, conquered the city and massacred all its defenders. Thereafter he had the strategically located city repaired, provisioned and garrisoned with his best troops.[111]

Qadishaye, settled by

There is also a 7th-century text by an unidentified author, written about the legendary

Medieval period

Early Syriac sources use the terms Hurdanaye, Kurdanaye, Kurdaye to refer to the Kurds. According to

In the early

In 838, a Kurdish leader based in Mosul, named

In 934, the

In the 10th–12th centuries, a number of

- The Shaddadids (951–1174)[127][128][129][130] ruled parts of Armenia and Arran.

- The Rawadid (955–1221) They were Arab origin, later Kurdicized[130] and ruled Azerbaijan.

- The Hasanwayhids (959–1015)[129] ruled western Iran and upper Mesopotamia.

- The Marwanids (990–1096)[131][129][130] ruled eastern Anatolia.

- The Annazids (990–1117)[132][129] ruled western Iran and Upper Mesopotamia (succeeded the Hasanwayhids).

- The Hazaraspids (1148–1424)[133] ruled southwestern Iran.

- The Ayyubids (1171–1341)[134] ruled Egypt, Syria, Upper Mesopotamia, Hejaz, Yemen and parts of southeastern Anatolia.

Due to the Turkic invasion of Anatolia and Armenia, the 11th-century Kurdish dynasties crumbled and became incorporated into the Seljuk dynasty. Kurds would hereafter be used in great numbers in the armies of the

Safavid period

The

The Safavid king

The Kurds of Khorasan, numbering around 700,000, still use the

Zand period

After the fall of the Safavids, Iran fell under the control of the

The country would flourish during Karim Khan's reign; a strong resurgence of the arts would take place, and international ties were strengthened.

After Karim Khan's death, the dynasty would decline in favour of the rival

The Kurdish tribes present in

Ottoman period

When Sultan

The Ottoman centralist policies in the beginning of the 19th century aimed to remove power from the principalities and localities, which directly affected the Kurdish emirs.

The first modern Kurdish nationalist movement emerged in 1880 with an uprising led by a Kurdish landowner and head of the powerful Shemdinan family,

Kurdish nationalism of the 20th century

Kurdish nationalism emerged after

The Kurdish ethno-nationalist movement that emerged following World War I and the end of the Ottoman Empire in 1922 largely represented a reaction to the changes taking place in mainstream Turkey, primarily to the radical secularization, the centralization of authority, and to the rampant Turkish nationalism in the new Turkish Republic.[162]

Some of the Kurdish groups sought self-determination and the confirmation of Kurdish autonomy in the 1920

From 1922 to 1924 in Iraq a

During the 1920s and 1930s, several large-scale Kurdish revolts took place in Kurdistan. Following these rebellions, the area of Turkish Kurdistan was put under

Kurdish officers from the Iraqi army [...] were said to have approached Soviet army authorities soon after their arrival in Iran in 1941 and offered to form a Kurdish volunteer force to fight alongside the Red Army. This offer was declined.[166]

During the relatively open government of the 1950s in Turkey, Kurds gained political office and started working within the framework of the Turkish Republic to further their interests, but this move towards integration was halted with the

Kurds are often regarded as "the largest ethnic group without a state",[168][169][170][171][172][173] Some researchers, such as Martin van Bruinessen,[174] who seem to agree with the official Turkish position, argue that while some level of Kurdish cultural, social, political and ideological heterogeneity may exist, the Kurdish community has long thrived over the centuries as a generally peaceful and well-integrated part of Turkish society, with hostilities erupting only in recent years.[175][176][177] Michael Radu, who worked for the United States' Pennsylvania Foreign Policy Research Institute, notes that demands for a Kurdish state comes primarily from Kurdish nationalists, Western human-rights activists, and European leftists.[175]

Kurdish communities

Turkey

According to

Several large scale Kurdish revolts in 1925, 1930 and 1938 were suppressed by the Turkish government and more than one million Kurds were forcibly relocated between 1925 and 1938. The use of Kurdish language, dress,

The words "Kurds", "Kurdistan", or "Kurdish" were officially banned by the Turkish government.[186] Following the military coup of 1980, the Kurdish language was officially prohibited in public and private life.[187] Many people who spoke, published, or sang in Kurdish were arrested and imprisoned.[188] The Kurds are still not allowed to get a primary education in their mother tongue and they do not have a right to self-determination, even though Turkey has signed the ICCPR. There is ongoing discrimination against and "otherization" of Kurds in society.[189]

The Kurdistan Workers' Party or PKK (Kurdish: Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê) is Kurdish militant organization which has waged an armed struggle against the Turkish state for cultural and political rights and self-determination for the Kurds. Turkey's military allies the US, the EU, and NATO label the PKK as a terrorist organization while the UN,[190] Switzerland,[191] Russia,[192] and India have refused to add the PKK to their terrorist list.[193] Some of them have even supported the PKK.[194]

Between 1984 and 1999, the PKK and the Turkish military engaged in open war, and much of the countryside in the southeast was depopulated, as Kurdish civilians moved from villages to bigger cities such as Diyarbakır, Van, and Şırnak, as well as to the cities of western Turkey and even to western Europe. The causes of the depopulation included mainly the Turkish state's military operations, state's political actions, Turkish deep state actions, the poverty of the southeast and PKK atrocities against Kurdish clans which were against them.[195] Turkish state actions have included torture, rape,[196][197] forced inscription, forced evacuation, destruction of villages, illegal arrests and executions of Kurdish civilians.[198][199]

Since the 1970s, the European Court of Human Rights has condemned Turkey for the thousands of human rights abuses.[199][200] The judgments are related to executions of Kurdish civilians,[201] torturing,[202] forced displacements[203] systematic destruction of villages,[204] arbitrary arrests[205] murdered and disappeared Kurdish journalists.[206]

Leyla Zana, the first Kurdish female MP from Diyarbakir, caused an uproar in Turkish Parliament after adding the following sentence in Kurdish to her parliamentary oath during the swearing-in ceremony in 1994: "I take this oath for the brotherhood of the Turkish and Kurdish peoples."[207]

In March 1994, the

Officially protected death squads are accused of the disappearance of 3,200 Kurds and Assyrians in 1993 and 1994 in the so-called "mystery killings". Kurdish politicians, human-rights activists, journalists, teachers and other members of intelligentsia were among the victims. Virtually none of the perpetrators were investigated nor punished. Turkish government also encouraged Islamic extremist group Kurdish Hezbollah to assassinate suspected PKK members and often ordinary Kurds.[211] Azimet Köylüoğlu, the state minister of human rights, revealed the extent of security forces' excesses in autumn 1994: While acts of terrorism in other regions are done by the PKK; in Tunceli it is state terrorism. In Tunceli, it is the state that is evacuating and burning villages. In the southeast there are two million people left homeless.[212]

Iran

The

Unlike in other Kurdish-populated countries, there are strong ethnolinguistical and cultural ties between Kurds,

The

During the late 1910s and early 1920s,

As a response to growing

Several

Kurds have been well integrated in

Iraq

Kurds constitute approximately 17% of Iraq's population. They are the majority in at least three provinces in northern Iraq which are together known as Iraqi Kurdistan. Kurds also have a presence in Kirkuk, Mosul, Khanaqin, and Baghdad. Around 300,000 Kurds live in the Iraqi capital Baghdad, 50,000 in the city of Mosul and around 100,000 elsewhere in southern Iraq.[238]

Kurds led by

During the Iran–Iraq War in the 1980s, the regime implemented anti-Kurdish policies and a de facto civil war broke out. Iraq was widely condemned by the international community, but was never seriously punished for oppressive measures such as the mass murder of hundreds of thousands of civilians, the wholesale destruction of thousands of villages and the deportation of thousands of Kurds to southern and central Iraq.

The genocidal campaign, conducted between 1986 and 1989 and culminating in 1988, carried out by the Iraqi government against the Kurdish population was called Anfal ("Spoils of War"). The Anfal campaign led to destruction of over two thousand villages and killing of 182,000 Kurdish civilians.

After the collapse of the Kurdish uprising in March 1991, Iraqi troops recaptured most of the Kurdish areas and 1.5 million Kurds abandoned their homes and fled to the Turkish and Iranian borders. It is estimated that close to 20,000 Kurds succumbed to death due to exhaustion, lack of food, exposure to cold and disease. On 5 April 1991,

The Kurdish population welcomed the American troops in 2003 by holding celebrations and dancing in the streets.

Syria

Kurds account for 9% of Syria's population, a total of around 1.6 million people.[252] This makes them the largest ethnic minority in the country. They are mostly concentrated in the northeast and the north, but there are also significant Kurdish populations in Aleppo and Damascus. Kurds often speak Kurdish in public, unless all those present do not. According to Amnesty International, Kurdish human rights activists are mistreated and persecuted.[253] No political parties are allowed for any group, Kurdish or otherwise.

Techniques used to suppress the ethnic identity of Kurds in Syria include various bans on the use of the Kurdish language, refusal to register children with Kurdish names, the replacement of Kurdish place names with new names in Arabic, the prohibition of businesses that do not have Arabic names, the prohibition of Kurdish private schools, and the prohibition of books and other materials written in Kurdish.[254][255] Having been denied the right to Syrian nationality, around 300,000 Kurds have been deprived of any social rights, in violation of international law.[256][257] As a consequence, these Kurds are in effect trapped within Syria. In March 2011, in part to avoid further demonstrations and unrest from spreading across Syria, the Syrian government promised to tackle the issue and grant Syrian citizenship to approximately 300,000 Kurds who had been previously denied the right.[258]

On 12 March 2004, beginning at a stadium in Qamishli (a largely Kurdish city in northeastern Syria), clashes between Kurds and Syrians broke out and continued over a number of days. At least thirty people were killed and more than 160 injured. The unrest spread to other Kurdish towns along the northern border with Turkey, and then to Damascus and Aleppo.[259][260]

As a result of

Kurdish-inhabited

In October 2019, Turkey and the Syrian Interim Government began an offensive into Kurdish-populated areas in Syria, prompting about 100,000 civilians to flee from the area fearing that Turkey would commit an ethnic cleansing.[262][263]

Transcaucasus

Between the 1930s and 1980s, Armenia was a part of the Soviet Union, within which Kurds, like other ethnic groups, had the status of a protected minority. Armenian Kurds were permitted their own state-sponsored newspaper, radio broadcasts and cultural events. During the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, many non-Yazidi Kurds were forced to leave their homes since both the Azeri and non-Yazidi Kurds were Muslim.

In 1920, two Kurdish-inhabited areas of Jewanshir (capital

Diaspora

According to a report by the Council of Europe, approximately 1.3 million Kurds live in Western Europe. The earliest immigrants were Kurds from Turkey, who settled in Germany, Austria, the Benelux countries, the United Kingdom, Switzerland and France during the 1960s. Successive periods of political and social turmoil in the region during the 1980s and 1990s brought new waves of Kurdish refugees, mostly from Iran and Iraq under Saddam Hussein, came to Europe.[151] In recent years, many Kurdish asylum seekers from both Iran and Iraq have settled in the United Kingdom (especially in the town of Dewsbury and in some northern areas of London), which has sometimes caused media controversy over their right to remain.[265] There have been tensions between Kurds and the established Muslim community in Dewsbury,

There was substantial immigration of ethnic Kurds in

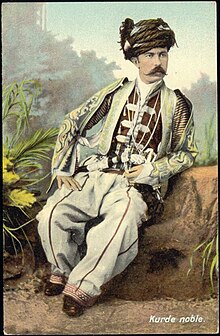

Culture

Kurdish culture is a legacy from the various ancient peoples who shaped modern Kurds and their society. As most other Middle Eastern populations, a high degree of mutual influences between the Kurds and their neighbouring peoples are apparent. Therefore, in Kurdish culture elements of various other cultures are to be seen. However, on the whole, Kurdish culture is closest to that of other

Education

A madrasa system was used before the modern era.[277][278] Mele are Islamic clerics and instructors.[279]

Women

In general, Kurdish women's rights and equality have improved in the 20th and 21st centuries due to progressive movements within Kurdish society. However, despite the progress, Kurdish and international women's rights organizations still report problems related to

Folklore

The Kurds possess a rich tradition of folklore, which, until recent times, was largely transmitted by speech or song, from one generation to the next. Although some of the Kurdish writers' stories were well known throughout Kurdistan; most of the stories told and sung were only written down in the 20th and 21st centuries. Many of these are, allegedly, centuries old.

Widely varying in purpose and style, among the Kurdish folklore one will find stories about nature,

Perhaps the most widely reoccurring element is the fox, which, through cunning and shrewdness triumphs over less intelligent species, yet often also meets his demise.[281] Another common theme in Kurdish folklore is the origin of a tribe.

Storytellers would perform in front of an audience, sometimes consisting of an entire village. People from outside the region would travel to attend their narratives, and the storytellers themselves would visit other villages to spread their tales. These would thrive especially during winter, where entertainment was hard to find as evenings had to be spent inside.[281]

Coinciding with the heterogeneous Kurdish groupings, although certain stories and elements were commonly found throughout Kurdistan, others were unique to a specific area; depending on the region, religion or dialect. The

During the criminalization of the Kurdish language after the coup d'état of 1980, dengbêj (singers) and çîrokbêj (tellers) were silenced, and many of the stories had become endangered. In 1991, the language was decriminalized, yet the now highly available radios and TV's had as an effect a diminished interest in traditional storytelling.[285] However, a number of writers have made great strides in the preservation of these tales.

Weaving

Kurdish weaving is renowned throughout the world, with fine specimens of both rugs and bags. The most famous Kurdish rugs are

Another well-known Kurdish rug is the Senneh rug, which is regarded as the most sophisticated of the Kurdish rugs. They are especially known for their great knot density and high-quality mountain wool.[286] They lend their name from the region of Sanandaj. Throughout other Kurdish regions like Kermanshah, Siirt, Malatya and Bitlis rugs were also woven to great extent.[287]

Kurdish bags are mainly known from the works of one large tribe: the

Handicrafts

Outside of weaving and clothing, there are many other Kurdish

Kurdish blades include a distinct jambiya, with its characteristic I-shaped hilt, and oblong blade. Generally, these possess double-edged blades, reinforced with a central ridge, a wooden, leather or silver decorated scabbard, and a horn hilt, furthermore they are often still worn decoratively by older men. Swords were made as well. Most of these blades in circulation stem from the 19th century.

Another distinct form of art from Sanandaj is 'Oroosi', a type of window where stylized wooden pieces are locked into each other, rather than being glued together. These are further decorated with coloured glass, this stems from an old belief that if light passes through a combination of seven colours it helps keep the atmosphere clean.

Among Kurdish Jews a common practice was the making of talismans, which were believed to combat illnesses and protect the wearer from malevolent spirits.

Tattoos

Adorning the body with tattoos (deq in Kurdish) is widespread among the Kurds; even though permanent tattoos are not permissible in Sunni Islam. Therefore, these traditional tattoos are thought to derive from pre-Islamic times.[289]

Tattoo ink is made by mixing

The popularity of permanent, traditional tattoos has greatly diminished among newer generation of Kurds. However, modern tattoos are becoming more prevalent; and temporary tattoos are still being worn on special occasions (such as henna, the night before a wedding) and as tribute to the cultural heritage.[289]

Music and dance

Traditionally, there are three types of Kurdish classical performers: storytellers (çîrokbêj), minstrels (stranbêj), and bards (dengbêj). No specific music was associated with the Kurdish princely courts. Instead, music performed in night gatherings (şevbihêrk) is considered classical. Several musical forms are found in this genre. Many songs are epic in nature, such as the popular Lawiks, heroic ballads recounting the tales of Kurdish heroes such as Saladin. Heyrans are love ballads usually expressing the melancholy of separation and unfulfilled love. One of the first Kurdish female singers to sing heyrans is Chopy Fatah, while Lawje is a form of religious music and Payizoks are songs performed during the autumn. Love songs, dance music, wedding and other celebratory songs (dîlok/narînk), erotic poetry, and work songs are also popular.[citation needed]

Throughout the Middle East, there are many prominent Kurdish artists. Most famous are

Cinema

The main themes of Kurdish cinema are the poverty and hardship which ordinary Kurds have to endure. The first films featuring Kurdish culture were actually shot in Armenia. Zare, released in 1927, produced by Hamo Beknazarian, details the story of Zare and her love for the shepherd Seydo, and the difficulties the two experience by the hand of the village elder.[291] In 1948 and 1959, two documentaries were made concerning the Yezidi Kurds in Armenia. These were joint Armenian-Kurdish productions; with H. Koçaryan and Heciye Cindi teaming up for The Kurds of Soviet Armenia,[292] and Ereb Samilov and C. Jamharyan for Kurds of Armenia.[292]

The first critically acclaimed and famous Kurdish films were produced by

Another prominent Kurdish film director is

Other prominent Kurdish film directors that are critically acclaimed include

Sports

The most popular sport among the Kurds is football. Because the Kurds have no independent state, they have no representative team in

On a national level, the Kurdish clubs of Iraq have achieved success in recent years as well, winning the

In Turkey, a Kurd named

Another prominent sport is wrestling. In

- Zhir-o-Bal (a style similar to Ilam;[296]

- Zouran-Patouleh, practised in Kurdistan;[296]

- Zouran-Machkeh, practised in Kurdistan as well.[296]

Furthermore, the most accredited of the traditional Iranian wrestling styles, the Bachoukheh, derives its name from a local Khorasani Kurdish costume in which it is practised.[296]

Kurdish medalists in the

, respectively.Architecture

The traditional Kurdish village has simple houses, made of mud. In most cases with flat, wooden roofs, and, if the village is built on the slope of a mountain, the roof on one house makes for the garden of the house one level higher. However, houses with a beehive-like roof, not unlike those in Harran, are also present.

Over the centuries many Kurdish architectural marvels have been erected, with varying styles. Kurdistan boasts many examples from ancient Iranian, Roman, Greek and Semitic origin, most famous of these include

The first genuinely Kurdish examples extant were built in the 11th century. Those earliest examples consist of the Marwanid Dicle Bridge in Diyarbakir, the Shadaddid Minuchir Mosque in Ani,[299] and the Hisn al Akrad near Homs.[300]

In the 12th and 13th centuries the Ayyubid dynasty constructed many buildings throughout the Middle East, being influenced by their predecessors, the Fatimids, and their rivals, the Crusaders, whilst also developing their own techniques.

In later periods too, Kurdish rulers and their corresponding dynasties and emirates would leave their mark upon the land in the form mosques, castles and bridges, some of which have decayed, or have been (partly) destroyed in an attempt to erase the Kurdish cultural heritage, such as the White Castle of the Bohtan Emirate. Well-known examples are

Most famous is the Ishak Pasha Palace of Dogubeyazit, a structure with heavy influences from both Anatolian and Iranian architectural traditions. Construction of the Palace began in 1685, led by Colak Abdi Pasha, a Kurdish bey of the Ottoman Empire, but the building would not be completed until 1784, by his grandson, Ishak Pasha.[306][307] Containing almost 100 rooms, including a mosque, dining rooms, dungeons and being heavily decorated by hewn-out ornaments, this Palace has the reputation as being one of the finest pieces of architecture of the Ottoman Period, and of Anatolia.

In recent years, the KRG has been responsible for the renovation of several historical structures, such as Erbil Citadel and the Mudhafaria Minaret.[308]

Genetics

A 2005 study genetically examined three different groups of

11 different Y-DNA haplogroups have been identified in Kurmanji-speaking Kurds in Turkey.

Modern Kurdish-majority entities and governments

- Kurdistan Region (1992 to date) – Autonomous region in Iraq

- Democratic Federation of Northern Syria(2013 to date) – Autonomy of Syria

Gallery

-

Mercier. Kurde (Asie) by Auguste Wahlen, 1843

-

Kurdish warriors byAmadeo Preziosi

-

Armenian, Turkish and Kurdish females in their traditional clothes, 1873

-

Zakho Kurds by Albert Kahn, 1910s

-

Kurdish Cavalry in the passes of the Caucasus mountains (The New York Times, January 24, 1915)

-

A Kurdish chief

-

A Kurdish woman and a child fromEastern Kurdistan, 2017

-

A group of Kurdish men with traditional clothing,Hawraman

-

A Kurdish man wearing traditional clothes, Erbil

-

A Kurdish woman fighter fromRojava

See also

- A Modern History of the Kurds by David McDowall

- Chechen Kurds

- History of the Kurdish people

- Kurdology

- Kurds in Georgia

- Kurds in Lebanon

- Kurds in Turkey

- Khorasani Kurds

- List of Kurdish dynasties and countries

- List of Kurdish organisations

- List of Kurdish people

- National symbols of the Kurds

- Origins of the Kurds

- Zaza Kurds

References

Explanatory notes

Citations

- ^ ISSN 1553-8133. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2015. A rough estimate in this edition gives populations of 14.3 million in Turkey, 8.2 million in Iran, about 5.6 to 7.4 million in Iraq, and less than 2 million in Syria, which adds up to approximately 28–30 million Kurds in Kurdistan or in adjacent regions. The CIA estimates are as of August 2015[update]– Turkey: Kurdish 18%, of 81.6 million; Iran: Kurd 10%, of 81.82 million; Iraq: Kurdish 15–20%, of 37.01 million, Syria: Kurds, Armenians, and other 9.7%, of 17.01 million.

- ^ a b c d e f The Kurdish Population by the Kurdish Institute of Paris, 2017 estimate. The Kurdish population is estimated at 15–20 million in Turkey, 10–12 million in Iran, 8–8.5 million in Iraq, 3–3.6 million in Syria, 1.2–1.5 million in the European diaspora, and 400k–500k in the former USSR—for a total of 36.4 million to 45.6 million globally.

- ^ ""Wir Kurden ärgern uns über die Bundesregierung" – Politik". Süddeutsche.de. 21 March 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ "Geschenk an Erdogan? Kurdisches Kulturfestival verboten". heise.de. 5 September 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ The cultural situation of the Kurds, A report by Lord Russell-Johnston, Council of Europe, July 2006.

- ^ Ismet Chériff Vanly, "The Kurds in the Soviet Union", in: Philip G. Kreyenbroek & S. Sperl (eds.), The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview (London: Routledge, 1992). pg 164: Table based on 1990 estimates: Azerbaijan (180,000), Armenia (50,000), Georgia (40,000), Kazakhstan (30,000), Kyrghizistan (20,000), Uzbekistan (10,000), Tajikistan (3,000), Turkmenistan (50,000), Siberia (35,000), Krasnodar (20,000), Other (12,000), Total 450,000

- ^ "3 Kurdish women political activists shot dead in Paris". CNN. 11 January 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ "NATO Membership for Sweden: Between Turkey and the Kurds". The Washington Institute. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "NATO bid reignites Sweden's dispute with Turkey over Kurds". POLITICO. 24 May 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ISSN 1101-2412. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "Diaspora Kurde". Institutkurde.org (in French). Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 г. Национальный состав населения Российской Федерации". Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ "The Kurdish Diaspora". Institut Kurde de Paris. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ "QS211EW – Ethnic group (detailed)". nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ "Ethnic Group – Full Detail_QS201NI" (PDF). Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ "Scotland's Census 2011 – National Records of Scotland – Ethnic group (detailed)" (PDF). Scotland Census. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ "Ethnic composition of Kazakhstan 2021". Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Information from the 2011 Armenian National Census" (PDF). Statistics of Armenia (in Armenian). Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Switzerland". Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ "Fakta: Kurdere i Danmark". Jyllandsposten (in Danish). 8 May 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Al-Khatib, Mahmoud A.; Al-Ali, Mohammed N. "Language and Cultural Shift Among the Kurds of Jordan" (PDF). p. 12. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ "Austria". Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ "Greece". Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ a b "2011–2015 American Community Survey Selected Population Tables". Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ "Ethnic Origin (279), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age (12) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2016 Census". 25 October 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ "Language according to age and sex by region 1990 – 2021". Statistics Finland. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Population/Census" (PDF). geostat.ge.

- ^ "Number of resident population by selected nationality" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ "Australia – Ancestry". 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Atlas of the Languages of Iran A working classification". Languages of Iran. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ Michiel Leezenberg (1993). "Gorani Influence on Central Kurdish: Substratum or Prestige Borrowing?" (PDF). ILLC – Department of Philosophy, University of Amsterdam: 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "Kurds in Turkey".

- ^ "Learn About Kurdish Religion".

- ^ "Kurds of Iran: The missing piece in the Middle East Puzzle".

- ^ Bois, Th.; Minorsky, V.; MacKenzie, D.N. (24 April 2012). "Kurds, Kurdistān". Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition. Vol. 5. Brill Online. p. 439.

The Kurds, an Iranian people of the Near East, live at the junction of (...)

- ISBN 9781598843637.

- ^ Nezan, Kendal. A Brief Survey of the History of the Kurds. Kurdish Institute of Paris.

- ISBN 978-0-292-75813-1.

- ^ Based on arithmetic from World Factbook and other sources cited herein: A Near Eastern population of 28–30 million, plus approximately a 2 million diaspora gives 30–32 million. If the highest (25%) estimate for the Kurdish population of Turkey, in Mackey (2002), proves correct, this would raise the total to around 37 million.

- ^ "Kurds". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Encyclopedia.com. 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ISBN 978-1135797041.

- ^ "Timeline: The Kurds' Quest for Independence".

- ^ Who are the Kurds? by BBC News, 31 October 2017

- ^ Asatrian, G. (2009). Prolegomena to the Study of the Kurds, Iran and the Caucasus. Vol. 13. pp. 1–58.

Generally, the etymons and primary meanings of tribal names or ethnonyms, as well as place names, are often irrecoverable; Kurd is also an obscurity

- JSTOR 4132112.

- ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2, (see footnote of p.257)

- ^ G. Asatrian, Prolegomena to the Study of the Kurds, Iran and the Caucasus, Vol.13, pp. 1–58, 2009: "Evidently, the most reasonable explanation of this ethnonym must be sought for in its possible connections with the Cyrtii (Cyrtaei) of the Classical authors."

- ^ Karnamak Ardashir Papakan and the Matadakan i Hazar Dastan. G. Asatrian, Prolegomena to the Study of the Kurds, Iran and the Caucasus, Vol.13, pp. 1–58, 2009. Excerpt 1: "Generally, the etymons and primary meanings of tribal names or ethnonyms, as well as place names, are often irrecoverable; Kurd is also an obscurity." "It is clear that kurt in all the contexts has a distinct social sense, 'nomad, tent-dweller.' It could equally be an attribute for any Iranian ethnic group having similar characteristics. To look for a particular ethnic sense here would be a futile exercise." P. 24: "The Pahlavi materials clearly show that kurd in pre-Islamic Iran was a social label, still a long way from becoming an ethnonym or a term denoting a distinct group of people."

- ^ McDowall, David. 2000. A Modern History of the Kurds. Second Edition. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 9.

- ^ G. Asatrian, Prolegomena to the Study of the Kurds, Iran and the Caucasus, Vol.13, pp. 1–58, 2009

- ^ a b c Paul, Ludwig (2008). "Kurdish Language". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2 December 2011. Writes about the problem of attaining a coherent definition of "Kurdish language" within the Northwestern Iranian dialect continuum. There is no unambiguous evolution of Kurdish from Middle Iranian, as "from Old and Middle Iranian times, no predecessors of the Kurdish language are yet known; the extant Kurdish texts may be traced back to no earlier than the 16th century CE." Ludwig Paul further states: "Linguistics itself, or dialectology, does not provide any general or straightforward definition of at which point a language becomes a dialect (or vice versa). To attain a fuller understanding of the difficulties and questions that are raised by the issue of the 'Kurdish language,' it is therefore necessary to consider also non-linguistic factors."

- ^ Geographic distribution of Kurdish and other Iranic languages Archived 18 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 978-90-04-38533-7.

- ^ "Kurdish Nationalism and Competing Ethnic Loyalties", Original English version of: "Nationalisme kurde et ethnicités intra-kurdes", Peuples Méditerranéens no. 68–69 (1994), 11–37. Excerpt: "This view was criticised by the linguist D. N. MacKenzie, according to whom there are but few linguistic features that all Kurdish dialects have in common and that are not at the same time found in other Iranian languages."

- ^ G. Asatrian, Prolegomena to the Study of the Kurds, Iran and the Caucasus, Vol.13, pp. 1–58, 2009: "The classification of the Kurdish dialects is not an easy task, despite the fact that there have been numerous attempts mostly by Kurdish authors to put them into a system. However, for the time being the commonly accepted classification of the Kurdish dialects is that of the late Prof. D. N. Mackenzie, the author of fundamental works in Kurdish dialectology (see Mackenzie 1961; idem 1961–1962; idem 1963a; idem 1981), who distinguished three groups of dialects: Northern, Central, and Southern."

- ^ Nodar Mosaki (14 March 2012). "The zazas: a kurdish sub-ethnic group or separate people?". Zazaki.net. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ "Iranian languages". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ ISBN 9780393051414.]

As much as 25% of Turkey is Kurdish

This would raise the population estimate by about 5 million.[dubious - ^ Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs (9 March 2012). "Background Note: Syria". State.gov. Washington, DC: US State Department. Retrieved 2 August 2015. The CIA World Factbook reports all non-Arabs make up 9.7% of the Syrian population, but does not break out the Kurdish figure separately. However, this State Dept. source provides a figure of 9%. As of August 2015[update], the current document at this state.gov URL no longer provides such ethnic group data.

- ^ Hassanpour, Amir (7 November 1995). "A Stateless Nation's Quest for Sovereignty in the Sky". Concordia University. Archived from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2015. Paper presented at the Freie Universitat Berlin. For the figure, cites: McDowall, David (1992). "The Kurds: A Nation Denied". London: Minority Rights Group.

- ^ "The Kurds of Caucasia and Central Asia have been cut off for a considerable period of time and their development in Russia and then in the Soviet Union has been somewhat different. In this light the Soviet Kurds may be considered to be an ethnic group in their own right." The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire "Kurds". Institute of Estonia (EKI). Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ Ismet Chériff Vanly, "The Kurds in the Soviet Union", in: Philip G. Kreyenbroek & S. Sperl (eds.), The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview (London: Routledge, 1992), p. 164: Table based on 1990 estimates: Azerbaijan (180,000), Armenia (50,000), Georgia (40,000), Kazakhstan (30,000), Kyrgyzstan (20,000), Uzbekistan (10,000), Tajikistan (3,000), Turkmenistan (50,000), Siberia (35,000), Krasnodar (20,000), Other (12,000) (total 410,000).

- hdl:11693/26432. Archived from the original(PDF) on 18 December 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- CiteSeerX 10.1.1.545.8465.

- ISBN 9781873194300.

- OCLC 879288867.

- ISSN 1874-7094.

- OCLC 999248462.

- ISBN 978-0-7734-9004-8.

- ^ ISBN 9780199340378. Archivedfrom the original on 11 March 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ OCLC 772844849.

- ISBN 9780739177754.

- ISBN 978-1-317-23378-7.

- ISBN 978-1-108-58301-5.

- OCLC 999248462.

- OCLC 879288867.

- ^ "About Yarsan, a religious minority in Iran and Yarsani asylum seekers – Yarsanmedia" (in Persian). Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ISBN 0-930872-48-7.

- ^ Hinnel, J (1997), The Penguin Dictionary of Religion, Penguin Books UK

- ^ a b "Hopes for Zoroastrianism revival in Kurdistan as first temple opens its doors". Rudaw. 21 September 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- JSTOR 2843309.

- ^ Hervas, L. Saggio. (1787). 'Pratico delle lingue: con prolegomeni, e una raccolta di orazioni dominicali in piu di trecento lingue e dialetti...'. Cesena: Per Gregorio Biasini, pp. 156–157.

- ^ A Muslim Leader Converted to Christianity in Iraqi Kurdistan

- ^ "The Kurds". Urbana. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ "Christianity grows in Syrian town once besieged by Islamic State". Reuters. 16 April 2019 – via www.reuters.com.

- ISBN 978-5-02-017569-3, It is clear from the account of these Armenian historians that Ivane's great-grandfather broke away from the Kurdish tribe of Babir

- ISBN 978-0-521-05735-6, According to a tradition which has every reason to be true, their ancestors were Mesopotamian Kurds of the tribe (xel) Babirakan.

- ISBN 978-0-227-67931-9, under the Christianized Kurdish dynasty of Zak'arids they tried to re-establish nazarar system...

- S2CID 162528712.

- ISBN 9781438126760. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- JSTOR 4132112.

- ^ Mark Marciak Sophene, Gordyene, and Adiabene: Three Regna Minora of Northern Mesopotamia Between East and West, 2017. [1] pp. 220–221

- ^ Victoria Arekelova, Garnik S. Asatryan Prolegomena To The Study Of The Kurds, Iran and The Caucasus, 2009 [2] pp. 82

- ISSN 2360-266X.

- ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- ^ Frye, Richard Nelson. "Iran v. Peoples of Iran (1) A General Survey". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-292-75813-1.

- ISBN 978-0415072656.

- ^ G. Asatrian, Prolegomena to the Study of the Kurds, Iran and the Caucasus, Vol.13, pp.1-58, 2009. (p.21)

- .

- ISBN 9780521200912.

- ^ Schmitt, Rüdiger (15 December 1993). "Cyrtians". Iranica Online.

- ^ Martin van Bruinessen, "The ethnic identity of the Kurds," in: Ethnic groups in the Republic of Turkey, compiled and edited by Peter Alford Andrews with Rüdiger Benninghaus [=Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients, Reihe B, Nr.60]. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwich Reichert, 1989, pp. 613–21. excerpt: "The ethnic label "Kurd" is first encountered in Arabic sources from the first centuries of the Islamic era; it seemed to refer to a specific variety of pastoral nomadism, and possibly to a set of political units, rather than to a linguistic group: once or twice, "Arabic Kurds" are mentioned. By the 10th century, the term appears to denote nomadic and/or transhumant groups speaking an Iranian language and mainly inhabiting the mountainous areas to the South of Lake Van and Lake Urmia, with some offshoots in the Caucasus. ... If there was a Kurdish-speaking subjected peasantry at that time, the term was not yet used to include them.""The Ethnic Identity of the Kurds in Turkey" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ A. Safrastian, Kurds and Kurdistan, The Harvill Press, 1948, p. 16 and p. 31

- ISBN 978-1-59884-363-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85043-416-0.

- ^ Kârnâmag î Ardashîr î Babagân. Trans. D. D. P. Sanjana. 1896

- ^ .

- .

- ^ a b "The Seven Great Monarchies, by George Rawlinson, The Seventh Monarchy, Part A". Retrieved 2 March 2014 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ISBN 9780521246934.

- ISBN 9780931500084.

- S2CID 163337124.

- ^ Walker, J. T. (2006). The Legend of Mar Qardagh: Narrative and Christian Heroism in Late Antique Iraq. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 26, 52.

- ^ Mouawad, R.J. (1992). "The Kurds and Their Christian Neighbors: The Case of the Orthodox Syriacs". Parole de l'Orient. XVII: 127–141.

- ^ James, Boris. (2006). Uses and Values of the Term Kurd in Arabic Medieval Literary Sources. Seminar at the American University of Beirut, pp. 6–7.

- ^ James, Boris. (2006). Uses and Values of the Term Kurd in Arabic Medieval Literary Sources. Seminar at the American University of Beirut, pp. 4, 8, 9.

- ISBN 9789004385337.

- S2CID 143606283.

- State University of New York Press, 1989, p. 121.

- ^ T. Bois. (1966). The Kurds. Beirut: Khayat Book & Publishing Company S.A.L., p. 87.

- ^ K. A. Brook. (2009). The Jews of Khazaria. Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc., p. 184.

- ^ Canard (1986), p. 126

- ^ Kennedy (2004), pp. 266, 269.

- ^ K. M. Ahmed. (2012). The beginnings of ancient Kurdistan (c. 2500–1500 BC) : a historical and cultural synthesis. Leiden University, pp. 502–503.

- ^ Bosworth 1996, p. 151.

- ^ Peacock 2000.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy 2016, p. 215.

- ^ a b c Vacca 2017, p. 7.

- ^ Bosworth 1996, p. 89.

- ^ Aḥmad 1985, p. 97–98.

- ^ Bosworth 2003, p. 93.

- ^ Mazaheri & Gholami 2008.

- ^ F. Robinson. (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 44.

- ^ Riley-Smith 2008, p. 64.

- ^ Humphreys 1977, p. 29.

- ^ Laine 2015, p. 133.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 166.

- ISBN 978-0-86698-475-1.

- ^ American Society of Genealogists. 1997. p. 244.

- ^ Amoretti & Matthee 2009: "Of Kurdish ancestry, the Ṣafavids started as a Sunnī mystical order (...)"

Matthee 2005, p. 18: "The Safavids, as Iranians of Kurdish ancestry and of nontribal background, did not fit this pattern, although the stat they set up with the aid of Turkmen tribal forces of Eastern Anatolia closely resembled this division in its makeup. Yet, the Turk versus Tajik division was not impregnable."

Matthee 2008: "As Persians of Kurdish ancestry and of a non-tribal background, the Safavids did not fit this pattern, though the state they set up with the assistance of Turkmen tribal forces of eastern Anatolia closely resembled this division in its makeup."

Savory 2008, p. 8: "This official version contains textual changes designed to obscure the Kurdish origins of the Safavid family and to vindicate their claim to descent from the Imams."

Hamid 2006, p. 456–474: "The Safavids originated as a hereditary lineage of Sufi shaikhs centered on Ardabil, Shafeʿite in school and probably Kurdish in origin."

Amanat 2017, p. 40 "The Safavi house originally was among the landowning nobility of Kurdish origin, with affinity to the Ahl-e Haqq in Kurdistan (chart 1). In the twelfth century, the family settled in northeastern Azarbaijan, where Safi al-Din Ardabili (d. 1334), the patriarch of the Safavid house and Ismail's ancestor dating back six generations, was a revered Sufi leader."

Tapper 1997, p. 39: "The Safavid Shahs who ruled Iran between 1501 and 1722 descended from Sheikh Safi ad-Din of Ardabil (1252–1334). Sheikh Safi and his immediate successors were renowned as holy ascetics Sufis. Their own origins were obscure; probably of Kurdish or Iranian extraction, they later claimed descent from the Prophet."

Manz 2021, p. 169: "The Safavid dynasty was of Iranian – probably Kurdish – extraction and had its beginnings as a Sufi order located at Ardabil near the eastern border of Azerbaijan, in a region favorable for both agriculture and pastoralism." - Kurdistan, from where, seven generations before him, Firuz Shah Zarin-kulah had migrated to Adharbayjan"

- ^ Barry D. Wood, The Tarikh-i Jahanara in the Chester Beatty Library: an illustrated manuscript of the "Anonymous Histories of Shah Isma'il", Islamic Gallery Project, Asian Department Victoria & Albert Museum London, Routledge, Volume 37, Number 1 / March 2004, Pp: 89 – 107.

- ^ A People Without a Country: The Kurds and Kurdistan By Gérard Chaliand, Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou, and Marco Pallis, p. 205.

- ^ Blow 2009, p. 66.

- ^ Aslanian 2011, p. 1.

- ^ Bournoutian 2002, p. 208.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2015, pp. 291, 536.

- ^ Floor & Herzig 2012, p. 479.

- ^ a b "The cultural situation of the Kurds, A report by Lord Russell-Johnston, Council of Europe, July 2006. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "Fifteenth periodic report of States parties due in 1998: Islamic Republic of Iran". Unhchr.ch. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Matthee.

- Lak tribe Sir Percy Molesworth Sykes (1930). A History of Persia. Macmillan and Company, limited. p. 277.

- ^ a b J. R. Perry (2011) "Karim Khan Zand". Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ 'Abd al-Hamid I, M. Cavid Baysun, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. I, ed. H.A.R. Gibb, J.H. Kramers, E. Levi-Provençal and J. Schacht, (Brill, 1986), 62.

- ^ Dionisius A. Agius, In the Wake of the Dhow: The Arabian Gulf and Oman, (Ithaca Press, 2010), 15.

- ^ P. Oberling (2004) "Kurdish Tribes". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-7914-5993-5. Pg 95.

- ISBN 978-0-7914-5993-5. Pg 75.

- ^ S2CID 144607707. Archived from the originalon 11 October 2007. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

- S2CID 220375529. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

- ISBN 978-1-4000-7517-1

- ^ Dominik J. Schaller, Jürgen Zimmerer, Late Ottoman genocides: the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and Young Turkish population and extermination policies—introduction, Journal of Genocide Research, Vol.10, No.1, p.8, March 2008.

- ^ C. Dahlman, "The Political Geography of Kurdistan," Eurasian Geography and Economics, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2002, p. 279.

- ^

ISBN 9780815630937.

Kurdish officers from the Iraqi army [...] were said to have approached Soviet army authorities soon after their arrival in Iran in 1941 and offered to form a Kurdish volunteer force to fight alongside the Red Army. This offer was declined.

- ^ Abdullah Öcalan, Prison Writings: The Roots of Civilisation, 2007, Pluto Press, pp. 243–277.

- ^ Kennedy, J. Michael (17 April 2012). "Kurds Remain on the Sideline of Syria's Uprising". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-313-32110-8.

The fourth-largest ethnic group in the Middle East, the Kurds make up the world's most numerous ethnic group that has, with the exception of northern Iraq, no legal form of self-government.

- ISBN 978-1-4614-0447-7.

Many scholars and organizations refer to the Kurds as being one of the largest ethnic groups without a nation-state (Council of Europe, 2006; MacDonald, 1993; McKeirnan, 1999).

- ISBN 978-1-84885-546-5.

The Kurds appear to be the largest ethnic group in the world without a state of their own.

- ISBN 978-0-312-30597-0.

The 1999 capture and conviction of Kurdish guerilla leader Abdullah Ocalan brought increasing international attention to the Kurds, the largest ethnic group in the world without its own nation.

- ISBN 978-0-8160-7151-7.

They are a recognizable ethnic community, the 'world's largest ethnic group without a state of their own.'

- OCLC 46851965.

- ^ OCLC 50269670.

- ^ OCLC 714725127.

- OCLC 259715774.

- Ekurd.net. 21 March 2008. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Ethnologue census of languages in Asian portion of Turkey". Ethnologue.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Turkey – Population". Countrystudies.us. 31 December 1994. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ISSN 1773-0546.

- ^ "Linguistic and Ethnic Groups in Turkey". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-8122-1572-4(see page 186).

- ISBN 978-0-521-62096-3(see page 340)

- ISBN 978-0-521-62096-3(see page 348)

- ISBN 978-1-4724-2562-1.

- ^ Toumani, Meline. Minority Rules, The New York Times, 17 February 2008

- ISBN 978-1107054608.

- ^ "Kurdophobia". rightsagenda.org. Human Right Agenda Assosication. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ^ "The List established and maintained by the 1267/1989 Committee". United Nations Security Council Committee 1267. United Nations. 14 October 2015. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ St.Galler Tagblatt AG. "tagblatt.ch – Schlagzeilen". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ "Rus Aydın: PKK Terör Örgütü Çıkmaza Girdi". Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- List of designated terrorist organizations

- ^ Union européenne. "EUR-Lex – L:2008:188:TOC – EN – EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu.

- .

- ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- from the original on 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Still critical: Prospects in 2005 for Internally Displaced Kurds in Turkey" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. 17 (2(D)): 5–7. March 2005.

The local gendarmerie (soldiers who police rural areas) required villages to show their loyalty by forming platoons of "provisional village guards," armed, paid, and supervised by the local gendarmerie post. Villagers were faced with a frightening dilemma. They could become village guards and risk being attacked by the PKK or refuse and be forcibly evacuated from their communities. Evacuations were unlawful and violent. Security forces would surround a village using helicopters, armored vehicles, troops, and village guards, and burn stored produce, agricultural equipment, crops, orchards, forests, and livestock. They set fire to houses, often giving the inhabitants no opportunity to retrieve their possessions. During the course of such operations, security forces frequently abused and humiliated villagers, stole their property and cash, and ill-treated or tortured them before herding them onto the roads and away from their former homes. The operations were marked by scores of "disappearances" and extrajudicial executions. By the mid-1990s, more than 3,000 villages had been virtually wiped from the map, and, according to official figures, 378,335 Kurdish villagers had been displaced and left homeless.

- ^ a b "EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS: Turkey Ranks First in Violations in between 1959–2011". Bianet. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ Annual report (PDF) (Report). 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ The European Court of Human Rights: Case of Benzer and others v. Turkey (PDF) (Report). 24 March 2014. p. 57. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ The prohibition of torture (PDF) (Report). 2003. pp. 11, 13. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ Human Rights Watch. HRW. 2002. p. 7.

- ISBN 9781467879729. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ "Police arrest and assistance of a lawyer" (PDF). 2015. p. 1.

- ^ "Justice Comes from European Court for a Kurdish Journalist". Kurdish Human Rights Project. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ Michael M. Gunter, The Kurds and the future of Turkey, 194 pp., Palgrave Macmillan, 1997. (p.66)

- ^ Michael M. Gunter, The Kurds and the future of Turkey, 194 pp., Palgrave Macmillan, 1997. (pp. 15, 66)

- ^ Bulent Gokay, The Kurdish Question in Turkey: Historical Roots, Domestic Concerns and International Law, in Minorities, Peoples and Self-Determination, Ed. by Nazila Ghanea and Alexandra Xanthaki, 352 pp., Martinus Nijhoff/Brill Publishers, 2005. (p. 332)

- ^ "Election results 2009". Secim.haberler.com. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ISBN 0-8133-3580-9, p.258

- ISBN 0-8133-3580-9, p.259

- ^ McLachlan, Keith (15 December 1989). "Boundaries i. With the Ottoman Empire". Encyclopædia Iranica. New York: Columbia University. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ a b Schofield, Richard N. (15 December 1989). "Boundaries v. With Turkey". Encyclopædia Iranica. New York: Columbia University. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ a b Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (20 July 2005). "Kurdish Written Literature". Encyclopædia Iranica. New York: Columbia University. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ OCLC 24247652.

- OCLC 7975938.

- ^ OCLC 24247652.

- ^ OCLC 13762196.

- ^ a b c Ashraf, Ahmad (15 December 2006). "Iranian Identity iv. 19th–20th Centuries". Encyclopædia Iranica. New York: Columbia University. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- OCLC 7975938.

- ^ OCLC 430736528.

- OCLC 1102813.

- OCLC 54059369.

- ^ Parvin, Nassereddin (15 December 2006). "Iran-e Kabir". Encyclopædia Iranica. New York: Columbia University. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ Zabih, Sepehr (15 December 1992). Communism ii.. in Encyclopædia Iranica. New York: Columbia University

- OCLC 61425259.

- OCLC 16923212.

- OCLC 7975938.

- OCLC 1219525.

- ^ OCLC 61425259.

- OCLC 7975938.

- OCLC 9282694.

- ^ OCLC 756496931.

- OCLC 753913763.

- ^ OCLC 54966573.

- OCLC 171111098.

- ^ "By Location". Adherents.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2000. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ G.S. Harris, Ethnic Conflict and the Kurds in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, pp. 118–120, 1977

- ^ Introduction. Genocide in Iraq: The Anfal Campaign Against the Kurds (Human Rights Watch Report, 1993).

- ^ G.S. Harris, Ethnic Conflict and the Kurds in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, p.121, 1977

- ^ M. Farouk-Sluglett, P. Sluglett, J. Stork, Not Quite Armageddon: Impact of the War on Iraq, MERIP Reports, July–September 1984, p.24

- ^ "The Prosecution Witness and Documentary Evidence Phases of the Anfal Trial" (PDF). International Center for Transitional Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2008. According to the Chief Prosecutor, Iraqi forces repeatedly used chemical weapons, killed up to 182,000 civilians, forcibly displaced hundreds of thousands more, and almost completely destroyed local infrastructure.

- ^ Security Council Resolution 688, 5 April 1991.

- ^ Johnathan C. Randal, After such knowledge, what forgiveness?: my encounters with Kurdistan, Westview Press, 368 pp., 1998. (see pp. 107–108)

- ^ [3] Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Kurds Rejoice, But Fighting Continues in North". Fox News Channel. 9 April 2003. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013.

- ^ "Coalition makes key advances in northern Iraq – April 10, 2003". CNN. 10 April 2003. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Daniel McElroy. "Grateful Iraqis Surrender to Kurds". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Full Text of Iraqi Constitution, The Washington Post, October 2005.

- ^ "USCIRF Annual Report 2009 – Countries of Particular Concern: Iraq". Refworld. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- ^ "World Gazetteer". Gazetteer.de. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Syria: End persecution of human rights defenders and human rights activists Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Syria: The Silenced Kurds". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Essential Background: Overview of human rights issues in Syria. Human Rights Watch, 31 December 2004. Archived 10 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Washington, D.C. (2 September 2005). "Syria's Kurds Struggle for Rights". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Vinsinfo. "The Media Line". The Media Line. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Syria to tackle Kurd citizenship problem – Just In (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 1 April 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Syria: Address Grievances Underlying Kurdish Unrest". Human Rights Watch. 18 March 2004. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Serhildana 12ê Adarê ya Kurdistana Suriyê.

- ^ "Displaced Kurds from Afrin need help, activist says". The Jerusalem Post. 26 March 2018.

- ^ "IS families escape Syria camp as Turkey battles Kurds". Agence France-Presse. 13 October 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds fear 'ethnic cleansing' after US troop pullout announcement". Fox News Channel. 7 October 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Kurds and Kurdistan: A General Background, p.22

- ^ "MP: Failed asylum seekers must go back – Dewsbury Reporter". Dewsburyreporter.co.uk. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "'I will not be muzzled' – Malik". Dewsburyreporter.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "UK Polling Report Election Guide: Dewsbury". Ukpollingreport.co.uk. 9 June 2012. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ "Hundreds of Syrian Kurdish migrants seek shelter in Serbia". Kurd Net – Ekurd.net Daily News. 29 August 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ "For Iraqi, Syrian Kurdish refugees, fantastic dreams and silent deaths". Kurd Net – Ekurd.net Daily News. 31 August 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". StatCan.GC.ca. Statistics Canada. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Detailed Mother Tongue, 2011 Census of Canada". StatCan.GC.ca. Statistics Canada. 24 October 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ^ "NPT Visits Our Next Door Neighbors in Little Kurdistan, USA". Nashville Public Television. 19 May 2008. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ^ "Nashville's new nickname: 'Little Kurdistan'". The Washington Times. 23 February 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ^ "Interesting Things About Nashville, Tennessee". USA Today. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ^ "The Kurdish Diaspora". institutkurde.org. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ "Iraqi Kurds". culturalorientation.net. Archived from the original on 2 September 2006.

- ^ Medrese education in northern Kurdistan dspace.library.uu.nl

- ^ Bruinessen, Martin (1998). "Zeynelabidin Zinar, Medrese education in Northern Kurdistan". Les Annales de l'Autre Islam. 5: 39–58. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ "Erdogan's new Kurdish allies". al-monitor.com. 5 February 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- PMID 24010850.

- ^ a b c Edgecomb, D. (2007). A Fire in My Heart: Kurdish Tales. Westport: Libraries Unlimited, pp. 200.

- ^ D. Shai (2008). "Changes in the oral tradition among the Jews of Kurdistan". Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ C. Alison (2006)."Yazidis i. General". Encyclopædia Iranica Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ V. Arakelova. "Shahnameh in the Kurdish and Armenian Oral Tradition" Archived 18 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ "Silenced Kurdish storytellers sing again". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ a b J. D. Winitz 'Kurdish Rugs'. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ Eagleton, W. (1989). "The Emergence of a Kurdish Rug Type". Oriental Rug Review. 9: 5.

- ^ Hopkins, M. (1989). "Diamonds in the Pile". Oriental Rug Review. 9: 5.

- ^ a b c "Immigration Museum (2010) Survival of a culture: Kurds in Australia" (PDF). Museumvictoria.com.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ W. Floor (2011) "Ḵālkubi" Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ IMDb 'Zare (1927)' Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ a b R. Alakom 'The first film about Kurds Archived 29 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine'. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ASIN 6302824435.

- ^ IMDb 'Bahman Ghobadi's Awards'. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ FIFA 'Eren Derdiyok's Profile'

- ^ a b c d Pahlevani Research Institute 'The Way of Traditional Persian Wrestling Styles Archived 11 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine' Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ "Kürt'üm, ay yıldızlı bayrağı gururla taşıyorum – Milliyet Haber". Gundem.milliyet.com.tr. 21 August 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ "Misha Aloyan wants to change his name – Armenian News". Tert.am. 21 October 2011. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ Sim, Steven. "The Mosque of Minuchihr". VirtualANI. Archived from the original on 20 January 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2007.

- ^ Kennedy 1994, p. 20[full citation needed]

- ^ Peterson, 1996, p.26.

- ^ Necipoğlu, 1994, pp.35–36.

- ISBN 1-905214-01-4p.226

- ISBN 978-2-940212-02-6, archived from the originalon 9 June 2012

- ISBN 1-74104-556-8

- ^ Lonely Planet (2012) 'Ishak Pasha Palace'. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ Institut kurde de Paris (2011) 'THE RESTORATION OF ISHAQ PASHA'S PALACE WILL BE COMPLETED IN 2013'. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ UNESCO Office for Iraq (2007) 'Revitalization Project of Erbil Citadel'. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ S2CID 23771698.

- ISSN 1874-2203.

General and cited references

- Aslanian, Sebouh (2011). From the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean: The Global Trade Networks of Armenian Merchants from New Julfa. California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520947573.

- Blow, David (2009). Shah Abbas: The Ruthless King Who Became an Iranian Legend. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857716767.

- ISBN 978-1568591414.

- Floor, Willem; Herzig, Edmund (2012). Iran and the World in the Safavid Age. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1850439301.

- Barth, F. 1953. Principles of Social Organization in Southern Kurdistan. Bulletin of the University Ethnographic Museum 7. Oslo.

- Hansen, H.H. 1961. The Kurdish Woman's Life. Copenhagen. Ethnographic Museum Record 7:1–213.

- Kennedy, Hugh (1994). Crusader Castles. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79913-3.

- Leach, E.R. 1938. Social and Economic Organization of the Rowanduz Kurds. London School of Economics Monographs on Social Anthropology 3:1–74.

- Longrigg, S.H. 1953. Iraq, 1900–1950. London.

- Masters, W.M. 1953. Rowanduz. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan.

- McKiernan, Kevin. 2006. The Kurds, a People in Search of Their Homeland. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-32546-6

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- Matthee, Rudi. "ŠAYḴ-ʿALI KHAN ZANGANA". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2008). The Crusades, Christianity, and Islam. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14625-8.

- Aḥmad, K. M. (1985). "ʿANNAZIDS". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II. Fasc. 1. pp. 97–98.

- Atmaca, Metin (2012). "Bābān". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Stewart, Devin J. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill. ISBN 9789004464582.

- Laine, James W. (2015). Meta-Religion: Religion and Power in World History. California University Press. ISBN 978-0-520-95999-6.

- Madelung, W. (1975). "The Minor Dynasties of Northern Iran". In Frye, R. N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6.

- Hassanpour, A. (1988). "BAHDĪNĀN". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III, Fasc. 5. p. 485.

- Lewis, Bernard (2002). Arabs in History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-158766-5.

- Spuler, B. (2012). "Faḍlawayh". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9789004161214.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2016). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East From the Sixth to the Eleventh Century (3nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9781317376392.

- Peacock, Andrew (2000). "SHADDADIDS". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Magoulias, Harry J. (1975). Decline and fall of Byzantium to the Ottoman Turks. State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-1540-8.

- Tapper, Richard (1997). Frontier Nomads of Iran: A Political and Social History of the Shahsevan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521583367.

- Bosworth, C.E (1996). The New Islamic Dynasties. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10714-3.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund (1994). "Daysam". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. VII, Fasc. 2. pp. 172–173.

- Humphreys, R. Stephen (1977). From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus, 1193–1260. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-87395-263-4.

- Vacca, Alison (2017). Non-Muslim Provinces under Early Islam: Islamic Rule and Iranian Legitimacy in Armenia and Caucasian Albania. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107188518.

- Mazaheri, Mas‘ud Habibi; Gholami, Rahim (2008). "Ayyūbids". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopedia Islamica. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16860-2.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund (2003). "HAZĀRASPIDS". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XII. Fasc. 1. p. 93.

- Matthee, Rudi (2005). The Pursuit of Pleasure: Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian History, 1500–1900. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3260-6.

- Hamid, Algar (2006). "IRAN ix. RELIGIONS IN IRAN (2) Islam in Iran (2.3) Shiʿism in Iran Since the Safavids". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XIII. Fasc. 5. pp. 456–474.

- Minorsky, Vladimir (2012). "Lak". Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). Brill Publishers. ISBN 9789004161214.

- Amoretti, Biancamaria Scarcia; Matthee, Rudi (2009). "Ṣafavid Dynasty". In Esposito, John L. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford University Press.

- Amanat, Abbas (2017). Iran: a Modern History. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300231465.

- Matthee, Rudi (2008). "SAFAVID DYNASTY". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Minorsky, V. (1953). Studies in Caucasian History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-05735-6.

- Savory, Roger (2008). "EBN BAZZĀZ". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. VIII. Fasc. 1. p. 8.

- Manz, Beatrice F. (2021). Nomads in the Middle East. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139028813.

Further reading

- Samir Amin (October 2016). The Kurdish Question Then and Now, in Monthly Review, Volume 68, Issue 05

- Dundas, Chad. "Kurdish Americans." Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 3, Gale, 2014), 3:41–52. online

- Eppel, Michael. A People Without a State: The Kurds from the Rise of Islam to the Dawn of Nationalism, 2016, University of Texas Press

- Maisel, Sebastian, ed. The Kurds: An Encyclopedia of Life, Culture, and Society. ABC-Clio, 2018.

- Shareef, Mohammed. The United States, Iraq and the Kurds: shock, awe and aftermath (Routledge, 2014).

Historiography

- Maxwell, Alexander; Smith, Tim (2015). "Positing 'not-yet-nationalism': limits to the impact of nationalism theory on Kurdish historiography". Nationalities Papers. 43 (5): 771–787. S2CID 143220624.

- Meho, Lokman I., ed. The Kurdish Question in U.S. Foreign Policy: A Documentary Sourcebook (Praeger, 2004).

- Sharif, Nemat. "A Brief History of Kurds and Kurdistan: Part I: From the Advent of Islam to AD 1750." The International Journal of Kurdish Studies 10.1/2 (1996): 105.

External links

- The Kurdish Institute of Paris Kurdish language, history, books and latest news articles.

- The Encyclopaedia of Kurdistan

- Istanbul Kurdish Institute

- The Kurdish Center of International Pen

- Kurdish Library, supported by the Swedish Government.

- Ethnic Cleansing and the Kurds

- The Kurds in the Ottoman Hungary by Zurab Aloian

- "The Other Iraq" Kurdish Information Website

The Kurdish issue in Turkey

- A report on the Kurdish IDP's – 2005

- A German newspaper's take on the Kurdish issue – 2005

- The Guardian – What's in a name? Too much in Turkey – 2001

- Sonia Roy (22 April 2011). "The impact on the politics of Iraq and Turkey and their bilateral relations regarding the Kurds in the post-Saddam regime". Foreign Policy Journal.