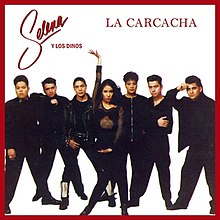

La Carcacha

| "La Carcacha" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Selena | ||||

| from the album Entre a Mi Mundo | ||||

| Released | April 1992 | |||

| Genre | Tejano cumbia | |||

| Length | 4:12 | |||

| Label | EMI Latin | |||

| Songwriter(s) | ||||

| Producer(s) | A.B. Quintanilla | |||

| Selena singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music Video | ||||

| "La Carcacha" on YouTube | ||||

"La Carcacha" (English: "The Jalopy") is a song recorded by American singer Selena for her third studio album, Entre a Mi Mundo (1992). The song was written by A.B. Quintanilla and Pete Astudillo. It was inspired by a dilapidated car and an experience in which A.B. observed a woman's willingness to court the owner of a luxury car. The song, characterized by its rhythmic melodies and satirical portrayal of life in the barrio, highlights the importance of love and genuine connection over material wealth. It is a Tejano cumbia song that is emblematic of Selena's typical style, while music critics found it to be musically similar to "Baila Esta Cumbia".

The song experienced considerable airplay and chart success, reaching the top spot on

Background and inspiration

In 1991, A.B. Quintanilla, Selena's brother, and the band's keyboardist Joe Ojeda walked from their hotel in Uvalde, Texas, to get food. While eating, A.B. observed a dilapidated vehicle and proclaimed his desire to compose a song inspired by it. He asked Ojeda for the Spanish translation of "broken-down car," which Ojeda provided as "carcacha". A.B. was initially uncertain about the thematic direction he would pursue with the composition.[1]

A month later after his observation of the run-down car, A.B. bought a BMW and went to pick up food. At the restaurant, a worker kept asking about his car, much to his frustration, as he simply sought to retrieve his meal. Overhearing a nearby woman expressing her willingness to court the owner of the car, A.B. utilized this experience to forge "La Carcacha" in collaboration with backup dancer and vocalist Pete Astudillo. Astudillo learned about A.B.'s idea in Eagle Pass, Texas, after a friend of Selena poked fun at a couple arriving at a dance in their beat-up car. Astudillo aspired to craft lyrics centered around a woman devoid of materialistic inclinations, whose acquaintances may deride her and engage in mockery. However, she lacks concern over her partner's possession of a battered car, showing that the paramount sentiment is the significance of love.[1]

Music and lyrics

Musically, "La Carcacha" is primarily a

"La Carcacha" employs a comical narrative intertwined with an underlying moral message.[1] The lyrics of "La Carcacha" revolve around a poignant commentary on materialism and superficiality. The narrative explores the protagonist's experience with a rundown vehicle, known as a "carcacha" in Spanish. By juxtaposing the protagonist's humble means of transportation with a materialistic young woman's desire for luxurious possessions, the song emphasizes the importance of love and genuine connection over material wealth.[15] In a 1992 interview at the Poteet Strawberry Saloon, Selena articulated her creative approach, stating that the music she and her band produced aimed to encapsulate the emotional experiences that people encounter throughout their lives. The songs they wrote, such as "La Carcacha", sought to connect with listeners by reflecting on common experiences.[16] Selena explained that the song's focus on "a clunker car" resonated with many individuals who found themselves in similar situations.[16] According to Jessica Roiz of Billboard, the lyrics of Selena's songs served as a vehicle for conveying valuable life lessons to listeners. In particular, Roiz noted that "La Carcacha" encourages individuals not to be ashamed of their possessions or lack thereof, championing the joys of embracing simplicity and deriving pleasure from the small things in life.[17] Billboard summarized the lyrics as Selena being ridiculed because of her relationship with a partner who owns a broken-down car and defending her partner despite his vehicle's subpar condition. With billowing tailpipe smoke, rudimentary wheels, and a reversed engine, Selena extols her partner's virtues, emphasizing his loyalty and devotion to her.[6]

Tejano music had often suffered from simplistic and generic lyrical content; however, A. B. and Astudillo overcame this stereotype by crafting songs that rendered vibrant depictions of life in the barrio.

Reception

The song experienced "considerable airplay" in several cities throughout Texas.[26] It debuted on local Tejano radio station charts during the week concluding on April 23, 1992.[27] "La Carcacha" ascended to the top spot on Radio & Records Tejano Singles chart on the week ending May 30, 1992.[28] It reached number 14 on Mexico's Grupera Songs chart on the week ending January 26, 1993.[29] In the week ending April 9, 2015, which marked the 16th anniversary of Selena's death, the song reached its peak at number six on the Regional Mexican Digital Song Sales chart.[30] The song peaked at number 16 on the US Latin Pop Digital Song Sales chart on the tracking week of December 16, 2020.[31] It peaked at number 21 on the Latin Digital Song Sales chart on the tracking week of December 16, 2020.[32] In 2017, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) certificated "La Carcacha" triple platinum (Latin), denoting 180,000 units consisting of sales and on-demand streaming in the US.[33]

During her 1993 Houston Astrodome concert, Selena's performance of "La Carcacha" led the audience to "[rise] to their feet",[34] a phenomenon also observed at her San Antonio Alamodome that same year.[35] Similarly, she won over people in Miami, Puerto Rico, and the Caribbean with songs like "La Carcacha", which compelled them to dance, as noted by Ed Crowell in the Austin-American Statesman.[36] The song served as the closing number for Selena's 1993 San Felipe Amphitheater concert, leaving attendees "wanting more".[37] Selena performed "La Carcacha" with an arm-swaying and hip-shaking routine, which had listeners of all ages engaged throughout and emulating the dance moves, according to Roiz.[6]

In May 1993, Selena released her Live! album, which was recorded during a free admissions concert in Corpus Christi, Texas that February. According to Tejano music columnist Rene Cabrera, "La Carcacha" and "La Llamada" (1993) overshadowed Selena's duet with Emilio Navaira on "Tu Robaste Mi Corazon" on the album.[38] The live version allowed the Los Dinos band to excel, providing a show that "[rocked] the house with dynamics and production values equal to any contemporary act's in this part of the planet", according to Patoski.[39] He observed that the live rendition did not necessitate language skills or familiarity with Latin culture for listeners to enjoy. Patoski also commended the keyboard lines, which were enhanced by Ricky Vela and David Lee Garza, and praised Garza's contribution of "street creditability and a touch of blues to his squeezebox instrumental break".[39] Leila Cobo found "La Caracacha" as an example of what Selena did best.[40]

"La Carcacha" was nominated for Single of the Year at the 1993 Tejano Music Awards,[41][42] though it was dropped during preliminaries.[43] Selena's first music video, shot in Monterrey, Mexico, was for "La Carcacha".[1] This was a rarity for Tejano musicians, as it was unusual for Tejano artists to employ music videos as promotional tools.[44] "La Carcacha" went on to win Video of the Year at the Tejano Music Awards,[45] and was recognized as one of the award-winning songs at the first BMI Latin Awards in 1994.[46] Selena's initial commercially successful singles in Mexico were "Baila Esta Cumbia" and "La Carcacha".[47]

Legacy and impact

"La Carcacha", along with "

The song served as the inspiration for a

In 2005,

In Netflix's two-part limited drama, Selena: The Series (which aired from 2020 to 2021), Gabriel Chavarria portrayed A. B. opposite Ricardo Chavira who played Abraham. In the last episode of the first part titled "Qué Creías", Abraham and A.B. engage in a dialogue concerning the song selection for Selena's (Christian Serratos) next album. Abraham queries A.B. about any cumbia tunes that could appeal to their current fanbase, to which A.B. responds with "La Carcacha". Abraham, however, disparages it as a novelty song about a dilapidated car and expresses doubt that such a song could attain hit status. A.B. concurs and expresses his commitment to crafting a better composition. Abraham escalates the pressure on A.B. by emphasizing the record company's requirement for a platinum record as a precondition for Selena's crossover album. He underscores the need for a chart-topping track in order to achieve this objective.[71]

Credits and personnel

Credits are adapted from the liner notes of Entre a Mi Mundo.[1]

|

|

Charts

|

|

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United States (RIAA)[33] | 3× Platinum (Latin) | 180,000‡ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

- ^ a b c d e Quintanilla 2002.

- ^ Anon. 1996, p. 75.

- ^ Campbell 1993, p. 53.

- ^ a b Huston-Crespo 2022.

- ^ Patoski 1993, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d e Roiz 2021.

- ^ Maldonado 1991, p. 31.

- ^ Garcia 1993a, p. 3.

- ^ Burr 1992a, p. T1.

- ^ Burr 1995, p. 1.

- ^ Burr 2004, pp. 601, 602.

- ^ Colloff 2010, p. 86.

- ^ Patoski 1996, p. 78.

- ^ Rodriguez 1995, p. 6G.

- ^ Flores 1994, p. 5.

- ^ a b Roiz 2019.

- ^ Roiz 2020.

- ^ Burr & Shannon 2003, p. 91.

- ^ Riemenschneider 1999, p. 38.

- ^ Echevarría Báez 2022.

- ^ a b Vargas 2012, p. 198.

- ^ Patoski 1996b, p. 1.

- ^ Patoski 1996, p. 100.

- ^ Flores 1995, p. 2.

- ^ Gamboa 1995, p. A5.

- ^ Cabrera 1992, p. 71.

- ^ Anon. & 1992 (a), p. 91.

- ^ a b Cabrera 1998, p. 67.

- ^ a b Anon. 1993, p. 40.

- ^ a b Anon. 2011, p. 39.

- ^ a b Anon. & 2020 (a).

- ^ a b Bustios 2020.

- ^ a b Anon. & n.d. (a).

- ^ Cabrera 1993b, p. 73.

- ^ Cabrera 1993c, p. 80.

- ^ Crowell 1995, p. 84.

- ^ Garcia 1993b, p. 1.

- ^ Cabrera 1996b, p. 70.

- ^ a b Patoski 1996b, p. 113.

- ^ Cobo 2002, p. 26.

- ^ Anon. 1992, p. 58.

- ^ Burr 1992b, p. 58.

- ^ Cabrera 1993a, p. 83.

- ^ Rosas & Hernandez 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Suarez 1993, p. 4.

- ^ Anon. 1994, p. 5.

- ^ Cabrera 1996a, p. 13.

- ^ Chirinos 2005, p. 1.

- ^ San-Juan 1992, p. 2.

- ^ Anon. 2005, p. 97.

- ^ Villareal 2020, p. C3.

- ^ Anon. & 1995 (b), p. 37.

- ^ Anon. 1995c, p. 37.

- ^ Burr 2001, p. 2F.

- ^ Gray 1995, p. 11.

- ^ Anon. 1993b, p. 39.

- ^ Clark 2002, p. 5.

- ^ Hernandez 1997, p. 7.

- ^ Corpus 1996, p. 1.

- ^ Hernandez 1997, p. 8.

- ^ Zamora 1997, p. 18.

- ^ Anon. 1995, p. 162.

- ^ Lawrence 1998, p. 22.

- ^ a b Anon. 2000, p. 18.

- ^ Maldonado 2000, p. 71.

- ^ Ovalle 2005, p. 140.

- ^ Olivas 2005, p. 47.

- ^ a b Anon. 2009.

- ^ Anon. 2018.

- ^ Anon. 2022.

- ^ Robles 2020.

Works cited

- "RIAA Gold & Platinum". RIAA.com. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- "1993 Tejano Music Award Nominations". El Paso Times. December 11, 1992. Retrieved March 29, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Tejano Singles > April 23, 1992". Austin American-Statesman. April 23, 1992. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Mexico Groupera Songs > January 26, 1993". El Siglo de Torreón (in Spanish). January 26, 1993. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2023 – via Elsiglodeterron.mx.

- "Selena y Los Dinos; Triunfan en La Onda Grupera". El Siglo de Torreón (in Spanish). August 4, 1993. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved June 2, 2023 – via Elsiglodetorreon.com.mx.

- "Los Premios Latinos de BMI" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 106, no. 12. Nielsen Media. March 19, 1994. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- "'La Carcacha' A Showstopper". The Odessa American. November 12, 1995. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Reaccionan Con Tristeza Los Haitantes de Los Dos Lareados Ante la Muerte de Selena". El Siglo de Terron. April 3, 1995. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2023 – via Elsiglodetorreon.com.mx.

- "Reaccionan Con Tristeza Los Habitantes de los dos Laredos Ante la Muerte de Selena". El Siglo de Terron (in Spanish). April 2, 1995. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved June 2, 2023 – via Elsiglodetorreon.com.mx.

- "1990 to 1995: Highlights of Selena's Recording Career". The Star Tribune. March 31, 1996. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Selena-dedicated 'Carcacha' to be Part of Fiesta". The Odessa American. April 30, 2000. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Una Reina del Tex-Mex". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. September 15, 2005. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Éxitos discográficos de la semana > June 26, 2009". ProQuest 433547168– via ProQuest.

- "Regional Mexican Digital Song Sales > April 9, 2011". Billboard. Vol. 123, no. 12. April 9, 2011. Gale A253627432– via Gale Research.

- "Watch Cuco Pay Tribute to Selena With His Cover of "La Carcacha"". Billboard.com. August 22, 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- "Latin Pop Digital Song Sales > July 15, 2020". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- "Esta es la canción de 2012 por la que acusan a Bellakath de plagio". ProQuest 2757013310– via ProQuest.

- Burr, Ramiro (March 14, 1992a). "The Young Turks of Tejano" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 104, no. 8. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- Burr, Ramiro (December 11, 1992b). "1993 Tejano Music Award Nominees". El Paso Times. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Burr, Ramiro (April 1, 1995). "Selena - April 16, 1971 - March 31, 1995". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved March 26, 2022 – via Newsbank.

- Burr, Ramiro (March 30, 2001). "Buzz: 'Selena' reopens as benefit show". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved April 1, 2022 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- Burr, Ramiro; Shannon, Doug (2003). Enclyopedia Latina. ISBN 0717258157.

- Burr, Ramiro (2004). Selena (2nd ed.). Schirmer Reference. Gale CX3428400473 – via Gale Research.

- Bustios, Pamela (December 16, 2020). "Selena Returns to Latin Pop Albums Chart With 'Selena: The Series Soundtrack'". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- Cabrera, Rene (July 24, 1992). "Selena, Mazz plan concerts here". Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Retrieved March 17, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cabrera, Rene (February 26, 1993a). "Mazz, Navaira Top Tejano Award Nominees". Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Retrieved March 27, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cabrera, Rene (March 5, 1993b). "Selena, David Lee Draw Crowd in Houston". Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Retrieved March 29, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cabrera, Rene (June 11, 1993c). "More than 33,000 Attended Alamadone Concert". Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Retrieved March 29, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cabrera, Rene (March 31, 1996a). "Rising Tide of Tejano". Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cabrera, Rene (October 18, 1996b). "Another Smash Selena CD Due Out". Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cabrera, Rene (May 29, 1998). "Double Bill on Saturday in Alice; Selena Still Atop Chart with Boxed Set". Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Campbell, Elizabeth (June 29, 1993). "Selena y Los Dinos Infect Tejano Rodeo with Dance Fever". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Chirinos, Fanny S (March 27, 2005). "Selena Fans Flock to City". Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- Clark, Michael D. (January 10, 2002). "Best Sounds of 2001". ProQuest 395808572– via ProQuest.

- Cobo, Leila (September 14, 2002). "Vital Reissues". Billboard. Vol. 114, no. 37. p. 96. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- Colloff, Pamela (April 2010). "Dreaming of Her". Texas Monthly. 38 (4). Gale A222555398– via Gale Research.

- Corpus, Lorena (April 1, 1996). "Por Siempre, Selena". Gale A13276416– via Gale Research.

- Crowell, Ed (April 6, 1995). "The Legend of Selena is Still in the Making". Austin-American Statesman. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Echevarría Báez, Mariam M. (August 26, 2022). "Nueva vida a la música de Selena". El Vocero (in Spanish). Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- Flores, John (April 3, 1995). "Mourners Say Singer Was Perfect Role Model". The Monitor. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Flores, Veronica (April 15, 1994). "Nothing Lost in Translation Selena Brings Grammy Winning Latin Sound to Town". ProQuest 257998188– via ProQuest.

- Garcia, Gus (July 20, 1993a). "Selena Del Rio-Bound". Del Rio News-Herald. Retrieved April 1, 2022 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- Garcia, Gus (July 26, 1993b). "Selena, Sunny Wow Crowd". Del Rio Herald-News. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Gray, Anthony (April 2, 1995). "Mexico Mourns Loss of La Reyna Tejana". The Brownsville Herald. Retrieved April 1, 2022 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- Gamboa, Suzanne (April 3, 1995). "Selena's Death Leaves Void in Hispanic Culture". Austin-American Statesman. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hernandez, Mary (April 1, 1997). "Su Voz 'inunda' Las Transmisiones". El Norte (in Spanish). Gale A128280959– via Gale Research.

- Huston-Crespo, Marysabel E. (March 31, 2022). "¿Cuál es la magia de Selena Quintanilla? El legado de la cantante tejana sigue intacto a más de un cuarto de siglo de su muerte". Gale A698927110– via Gale Research.

- Lawrence, Guy H (July 13, 1998). "Customizing Lowrider Cars Becoming a Family Affair". Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Maldonado, Vilma (October 31, 1991). "Selena y Los Dinos Receives Gold Album". The Monitor. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Maldonado, Vilma (March 31, 2000). "Musical Tribute to a Tejano Icon". The Monitor. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Olivas, Rogelio (April 14, 2005). "Decade After Selena's Death, Pals Shine in Touching Concert". Tuscan Citizen. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ovalle, Juan Martin (April 9, 2005). "Y El Espiritu de Selena Reino". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Patoski, Joe Nick (January 1993). "The Sound of Musica". Gale A13276416– via Gale Research.

- Patoski, Joe Nick (1996). Selena: Como La Flor. Boston: ISBN 0-316-69378-2.

- Patoski, Joe Nick (March 24, 1996b). "Remembering Selena". Austin-American Statesman. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Quintanilla, Selena (2002). Entre a Mi Mundo (Media notes). Suzette Quintanilla (spoken liner notes producer). EMI Latin.

- Riemenschneider, Chris (March 29, 1999). "Selena Redux is for Curious, Casual Fans". Austin-American Statesman. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Robles, Henry (December 4, 2020). "Qué Creías". Selena: The Series. Season 1. Episode 9. 30 minutes in. Netflix.

- Rodriguez, Estella (April 16, 1995). "Friends Remember Selena". Laredo Morning Times.

Mr. Quintanilla always wanted to hire Bird to be Selena's bodyguard, he says, and the group was always inviting him to tour with them. It was during one of those tours that Bird got involved in the recordings. "We were in the bus, and these guys were fixing this song called 'La Carcacha' -- in the bus! I just started doing a radio rap and bam, A.B. says, 'you're going to do it. I want that in the song.' " Bird recalls.

- Rosas, Hector; Hernandez, Mary (March 31, 2005). "Llega como plebeya y se va como reina". El Norte (in Spanish). Gale A131077116– via Gale Research.

- Roiz, Jessica (March 25, 2020). "Selena's Best Life Lessons in Her Lyrics: Staying Humble, Self-Worth & Living Life". Billboard. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- Roiz, Jessica (June 24, 2021). "The 100 Greatest Car Songs of All Time: Staff List". Billboard. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- Roiz, Jessica (June 10, 2019). "Selena Schools Us on a Very Important Life Lesson in This Rare 1992 Video: Watch". Billboard. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- San-Juan, Rocio (December 1992). "Selena y Los Dinos: La Revelacion del '92". Norteña Musical (23).

Entro fuerte y con el pie derecho cantando su "Carcacha", cancion que le dio el exito definintivo entre el publico Mexicano.

- Suarez, Carmen (March 21, 1993). "Award Show Honors Tejano Musicians". Abilene Reporter-News. Retrieved March 29, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Vargas, Deborah R. (2012). Dissonant divas in chicana music : the limits of la onda. ISBN 978-0816673162.

- Villareal, Yvonne (December 6, 2020). "Christian Serratos Knows She's Not Selena". Stateside Record and Landmark. Retrieved March 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Zamora, Fernando (May 3, 1997). "Solo Para Fans". El Norte (in Spanish). Gale A129991490– via Gale Research.