Late antiquity

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

Late antiquity is sometimes defined as spanning from the end of classical antiquity to the local start of the Middle Ages, from around the late 3rd century up to the 7th or 8th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin depending on location.[1] The popularisation of this periodization in English has generally been credited to historian Peter Brown, who proposed a period between 150–750 AD.[2] The Oxford Centre for Late Antiquity defines it as "the period between approximately 250 and 750 AD".[3] Precise boundaries for the period are a continuing matter of debate. In the West, its end was earlier, with the start of the Early Middle Ages typically placed in the 6th century, or even earlier on the edges of the Western Roman Empire.[citation needed]

Terminology

The term Spätantike, literally "late antiquity", has been used by German-speaking historians since its popularization by

The continuities between the later Roman Empire,[6] as it was reorganized by Diocletian (r. 284–305), and the Early Middle Ages are stressed by writers[who?] who wish to emphasize that the seeds of medieval culture were already developing in the Christianized empire, and that they continued to do so in the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantine Empire at least until the coming of Islam. Concurrently, some migrating Germanic tribes such as the Ostrogoths and Visigoths saw themselves as perpetuating the "Roman" tradition. While the usage "Late Antiquity" suggests that the social and cultural priorities of classical antiquity endured throughout Europe into the Middle Ages, the usage of "Early Middle Ages" or "Early Byzantine" emphasizes a break with the classical past, and the term "Migration Period" tends to de-emphasize the disruptions in the former Western Roman Empire caused by the creation of Germanic kingdoms within her borders beginning with the foedus with the Goths in Aquitania in 418.[7]

The general decline of population, technological knowledge and standards of living in Europe during this period became the archetypal example of societal collapse for writers from the Renaissance. As a result of this decline, and the relative scarcity of historical records from Europe in particular, the period from roughly the early fifth century until the Carolingian Renaissance (or later still) was referred to as the "Dark Ages". This term has mostly been abandoned as a name for a historiographical epoch, being replaced by "Late Antiquity" in the periodization of the late West Roman Empire, the early Byzantine Empire and the Early Middle Ages.[8]

Period history

The Roman Empire underwent considerable social, cultural and organizational changes starting with the reign of

The city of

Migrations of Germanic, Hunnic, and Slavic tribes disrupted Roman rule from the late 4th century onwards, culminating first in the Sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410 and subsequent Sack of Rome by the Vandals in 455, part of the eventual collapse of the Empire in the West itself by 476. The Western Empire was replaced by the so-called barbarian kingdoms, with the Arian Christian Ostrogothic Kingdom ruling Rome from Ravenna. The resultant cultural fusion of Greco-Roman, Germanic, and Christian traditions formed the foundations of the subsequent culture of Europe.[citation needed]

In the 6th century, Roman imperial rule continued in the East, and the

The middle of the 6th century was characterized by extreme climate events (

Religion

One of the most important transformations in late antiquity was the formation and evolution of the Abrahamic religions: Christianity, Rabbinic Judaism and, eventually, Islam.[citation needed]

A milestone in the

Constantine I was a key figure in many important events in Christian history, as he convened and attended the first ecumenical council of bishops at Nicaea in 325, subsidized the building of churches and sanctuaries such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, and involved himself in questions such as the timing of Christ's resurrection and its relation to the Passover.[12]

The birth of

Late antiquity marks the decline of

Many of the new religions relied on the emergence of the parchment codex (bound book) over the papyrus volumen (scroll), the former allowing for quicker access to key materials and easier portability than the fragile scroll, thus fueling the rise of synoptic exegesis, papyrology. Notable in this regard is the topic of the Fifty Bibles of Constantine.[citation needed]

Laity vs clergy

Within the recently legitimized Christian community of the 4th century, a division could be more distinctly seen between the

The rise of Islam

Islam appeared in the 7th century, spurring Arab armies to invade the Eastern Roman Empire and the

On the rise of Islam, two main theses prevail. On the one hand, there is the traditional view, as espoused by most historians prior to the second half of the twentieth century (and after) and by Muslim scholars. This view, the so-called "out of Arabia"-thesis, holds that Islam as a phenomenon was a new, alien element in the late antique world. Related to this is the

On the other hand, there is a more recent thesis, associated with scholars in the tradition of Peter Brown, in which Islam is seen to be a product of the late antique world, not foreign to it. This school suggests that its origin within the shared cultural horizon of the late antique world explains the character of Islam and its development. Such historians point to similarities with other late antique religions and philosophies—especially Christianity—in the prominent role and manifestations of piety in Islam, in Islamic asceticism and the role of "holy persons", in the pattern of universalist, homogeneous monotheism tied to worldly and military power, in early Islamic engagement with Greek schools of thought, in the apocalypticism of Islamic theology and in the way the Quran seems to react to contemporary religious and cultural issues shared by the late antique world at large. Further indication that Arabia (and thus the environment in which Islam first developed) was a part of the late antique world is found in the close economic and military relations between Arabia, the Byzantine Empire and the Sassanian Empire.[20] In recent years, the period of late antiquity has become a major focus in the fields of Quranic studies and Islamic origins.[21]

Political transformations

The late antique period also saw a wholesale transformation of the

]The Roman citizen elite in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, under the pressure of taxation and the ruinous cost of presenting spectacular public entertainments in the traditional

Cities

The later Roman Empire was in a sense a network of cities. Archaeology now supplements literary sources to document the transformation followed by collapse of cities in the

The city of Rome went from a population of 800,000 in the beginning of the period to a population of 30,000 by the end of the period, the most precipitous drop coming with the breaking of the

Concurrently, the continuity of the Eastern Roman Empire at

Justinian rebuilt his birthplace in Illyricum, as Justiniana Prima, more in a gesture of imperium than out of an urbanistic necessity; another "city", was reputed to have been founded, according to Procopius' panegyric on Justinian's buildings,[27] precisely at the spot where the general Belisarius touched shore in North Africa: the miraculous spring that gushed forth to give them water and the rural population that straightway abandoned their ploughshares for civilised life within the new walls, lend a certain taste of unreality to the project.[citation needed]

In mainland Greece, the inhabitants of

In the western Mediterranean, the only new cities known to be founded in Europe between the 5th and 8th centuries

Beyond the Mediterranean world, the cities of Gaul withdrew within a constricted line of defense around a citadel. Former imperial capitals such as Cologne and Trier lived on in diminished form as administrative centres of the Franks. In Britain most towns and cities had been in decline, apart from a brief period of recovery during the fourth century, well before the withdrawal of Roman governors and garrisons but the process might well have stretched well into the fifth century.[32] Historians emphasizing urban continuities with the Anglo-Saxon period depend largely on the post-Roman survival of Roman toponymy. Aside from a mere handful of its continuously inhabited sites, like York and London and possibly Canterbury, however, the rapidity and thoroughness with which its urban life collapsed with the dissolution of centralized bureaucracy calls into question the extent to which Roman Britain had ever become authentically urbanized: "in Roman Britain towns appeared a shade exotic," observes H. R. Loyn, "owing their reason for being more to the military and administrative needs of Rome than to any economic virtue".[33] The other institutional power centre, the Roman villa, did not survive in Britain either.[34] Gildas lamented the destruction of the twenty-eight cities of Britain; though not all in his list can be identified with known Roman sites, Loyn finds no reason to doubt the essential truth of his statement.[34]

Public building

In the cities the strained economies of Roman over-expansion arrested growth. Almost all new public building in late antiquity came directly or indirectly from the emperors or imperial officials. Attempts were made to maintain what was already there. The supply of free grain and oil to 20% of the population of Rome remained intact the last decades of the 5th century. It was once thought that the elite and rich had withdrawn to the private luxuries of their numerous villas and town houses. Scholarly opinion has revised this. They monopolized the higher offices in the imperial administration, but they were removed from military command by the late 3rd century. Their focus turned to preserving their vast wealth rather than fighting for it.[citation needed]

The

City life in the East, though negatively affected by the plague in the 6th–7th centuries, finally collapsed due to Slavic invasions in the Balkans and Persian destructions in Anatolia in the 620s. City life continued in Syria, Jordan and Palestine into the 8th. In the later 6th century street construction was still undertaken in

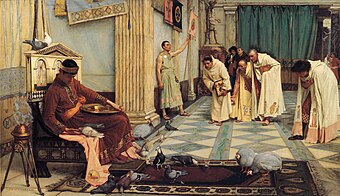

Sculpture and art

The stylistic changes characteristic of late antique art mark the end of classical

As the soldier emperors such as

From c. 300

Nearly all of these more abstracted conventions could be observed in the glittering mosaics of the era, which during this period moved from being decoration derivative from painting used on floors (and walls likely to become wet) to a major vehicle of religious art in churches. The glazed surfaces of the

As for luxury arts, manuscript illumination on vellum and parchment emerged from the 5th century, with a few manuscripts of Roman literary classics like the Vergilius Vaticanus and the Vergilius Romanus, but increasingly Christian texts, of which Quedlinburg Itala fragment (420–430) is the oldest survivor. Carved ivory diptychs were used for secular subjects, as in the imperial and consular diptychs presented to friends, as well as religious ones, both Christian and pagan – they seem to have been especially a vehicle for the last group of powerful pagans to resist Christianity, as in the late 4th century Symmachi–Nicomachi diptych.[47] Extravagant hoards of silver plate are especially common from the 4th century, including the Mildenhall Treasure, Esquiline Treasure, Hoxne Hoard, and the imperial Missorium of Theodosius I.[48]

Literature

In the field of literature, late antiquity is known for the declining use of

One genre of literature among Christian writers in this period was the Hexaemeron, dedicated to the composition of commentaries, homilies, and treatises concerned with the exegesis of the Genesis creation narrative. The first example of this was the Hexaemeron of Basil of Caesarea, with the first occurrence in Syriac literature being the Hexaemeron of Jacob of Serugh.[49]

Poetry

Greek poets of the late antique period included

Latin poets included

]Jewish poets included

See also

- Byzantine Empire

- Peter Brown

- Henri Pirenne

- Fall of the Western Roman Empire

- Early Middle Ages

- Migration Period

- Roman–Persian Wars

- Church of the priest Félix and baptistry of Kélibia

Notes

- ^ https://guides.loc.gov/late-antiquity. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- The World of Late Antiquity(1971)

- ^ https://www.ocla.ox.ac.uk/. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

- ^ A. Giardina, "Esplosione di tardoantico", Studi storici 40 (1999).

- ^ Glen W. Bowersock, "The Vanishing Paradigm of the Fall of Rome", Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 49.8 (May 1996:29–43) p. 34.

- ^ The Oxford Centre for Late Antiquity dates this as follows: "The late Roman period (which we are defining as, roughly, CE 250–450)..."

- ^ A recent thesis advanced by Peter Heather of Oxford posits the Goths, Hunnic Empire, and the Rhine invaders of 406 (Alans, Suevi, Vandals) as the direct causes of the Western Roman Empire's crippling; The Fall of the Roman Empire: a New History of Rome and the Barbarians, OUP 2005.

- ^ Gilian Clark, Late Antiquity: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford 2011), pp. 1–2.

- ISBN 978-0-521-81838-4.

- ISBN 0-8020-6369-1.

- ^ Brown, Authority and the Sacred

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Vita Constantini 3.5–6, 4.47

- OCLC 1148587171.

- ISBN 978-1-108-98931-2.

- ISBN 978-3-11-054378-0.

- ^ Smith, Rowland B.E. Julian's Gods: Religion and Philosophy in the Thought and Action of Julian

- ^ Jerome of Stridon wrote in c. 406 the polemical treatise Against Vigilantius in order to, among other disputes concerning relics of the saints, promote the greater spiritual nature of celibacy over marriage

- ^ Brown (1987) p. 270.

- ^ For a thesis on the complementary nature of Islam to the absolutist trend of Christian monarchy, see Garth Fowden, Empire to Commonwealth: Consequences of Monotheism in Late Antiquity, Princeton University Press 1993

- ^ Robert Hoyland, 'Early Islam as a Late Antique Religion', in: Scott F. Johnson ed., The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity (Oxford 2012) pp. 1053–1077.

- OCLC 1371946542.

- ^ Cf. the compendious list of ranks and liveries of imperial bureaucrats, the Notitia Dignitatum

- ^ 'The changing city' in "Urban changes and the end of Antiquity", Averil Cameron, The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity, CE 395–600, 1993:159ff, with notes; Hugh Kennedy, "From Polis to Madina: urban change in late Antique and early Islamic Syria", Past and Present 106 (1985:3–27).

- ISBN 9780582072978.

- ^ See Bryan Ward-Perkins, The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization, OUP 2005

- ^ Bibliography in Averil Cameron, The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity, CE 395–600, 1993:152 note 1.

- Buildings of JustinianVI.6.15; Vandal Wars I.15.3ff, noted by Cameron 1993:158.

- ^ Cameron 1993:159.

- ^ "Arte Visigótico: Recópolis"

- ^ According to E. A Thompson, "The Barbarian Kingdoms in Gaul and Spain", Nottingham Mediaeval Studies, 7 (1963:4n11).

- ^ José María Lacarra, "Panorama de la historia urbana en la Península Ibérica desde el siglo V al X," La città nell'alto medioevo, 6 (1958:319–358). Reprinted in Estudios de alta edad media española (Valencia: 1975), pp. 25–90.

- ISBN 978-90-485-5197-2.

- ^ Loyn 1991:15f.

- ^ a b Loyn 1991:16.

- ISBN 9783487151540.

- PMID 31792176.

- ISSN 0031-2746.

- ISSN 0950-3110.

- ^ Magalhães de Oliveira, Juan Caesar. "Late Antiquity: The Age of Crowds?*". Past and Present. 249 (1): 3–52.

- ^ Robert L. Vann, "Byzantine street construction at Caesarea Maritima", in R.L. Hohlfelder, ed. City, Town and Countryside in the Early Byzantine Ear 1982:167–70.

- ^ M. Whittow, "Ruling the late Roman and early Byzantine city: a continuous history", Past and Present 129 (1990:3–29).

- ^ Kitzinger 1977, pp. 2–21.

- ^ Kitzinger 1977, p. 9.

- ^ Kitzinger 1977, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Kitzinger 1977, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Kitzinger 1977, pp. 15–28.

- ^ Kitzinger 1977, pp. 29–34.

- ^ Kitzinger 1977, pp. 34–38.

- ^ Gasper 2024.

References

- Perry Anderson, Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism, NLB, London, 1974.

- ISBN 0-393-95803-5

- Peter Brown, Authority and the Sacred : Aspects of the Christianisation of the Roman World, Routledge, 1997, ISBN 0-521-59557-6

- Peter Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity 200–1000 CE, Blackwell, 2003, ISBN 0-631-22138-7

- Henning Börm, Westrom. Von Honorius bis Justinian, 2nd ed., ).

- ISBN 0-674-51194-8

- Averil Cameron, The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity CE 395–700, Routledge, 2011, ISBN 0-415-01421-2

- Averil Cameron et al. (editors), The Cambridge Ancient History, vols. 12–14, Cambridge University Press 1997ff.

- ISBN 978-0-19-954620-6

- John Curran, Pagan City and Christian Capital: Rome in the Fourth Century, Clarendon Press, 2000.

- Alexander Demandt, Die Spätantike, 2nd ed., Beck, 2007

- Peter Dinzelbacher and Werner Heinz, Europa in der Spätantike, Primus, 2007.

- Mateusz Fafinski, and Jakob Riemenschneider. Monasticism and the City in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Elements in Late Antique Religion 2. Cambridge: Camabridge University Press, 2023.

- Fabio Gasti, Profilo storico della letteratura tardolatina, Pavia University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-88-96764-09-1.

- Tomas Hägg (ed.) "SO Debate: The World of Late Antiquity revisited," in Symbolae Osloenses (72), 1997.

- Scott F. Johnson ed., The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity, Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-19-533693-1

- Arnold H.M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284–602; a social, economic and administrative survey, vols. I, II, University of Oklahoma Press, 1964.

- ISBN 0-571-11154-8.

- Bertrand Lançon, Rome in Late Antiquity: CE 313–604, Routledge, 2001.

- Noel Lenski (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Samuel N.C. Lieu and Dominic Montserrat(eds.), From Constantine to Julian: Pagan and Byzantine Views, A Source History, Routledge, 1996.

- Josef Lössl and Nicholas J. Baker-Brian (eds.), A Companion to Religion in Late Antiquity, Wiley Blackwell, 2018.

- Michael Maas (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian, Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Michael Maas (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Robert Markus, The end of Ancient Christianity, Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Ramsay MacMullen, Christianizing the Roman Empire C.E. 100–400, Yale University Press, 1984.

- Stephen Mitchell, A History of the Later Roman Empire. CE 284–641, 2nd ed., Blackwell, 2015.

- Michael Rostovtzeff (rev. P. Fraser), The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire, Oxford University Press, 1979.

- Johannes Wienand (ed.), Contested Monarchy. Integrating the Roman Empire in the Fourth Century CE, Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Gasper, Giles (2024). "On the Six Days of Creation: The Hexaemeral Tradition". In Goroncy, Jason (ed.). T&T Clark Handbook of the Doctrine of Creation. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 176–190.

External links

- New Advent – The Fathers of the Church, a Catholic website with English translations of the Early Fathers of the Church.

- ORB Encyclopedia's section on Late Antiquity in the Mediterranean from ORB

- Overview of Late Antiquity, from ORB

- Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics, a collaborative forum of Princeton and Stanford to make the latest scholarship on the field available in advance of final publication.

- The End of the Classical World, source documents from the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- Worlds of Late Antiquity, from the University of Pennsylvania

- Age of spirituality : late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century from The Metropolitan Museum of Art