Lawrence Sullivan Ross

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (July 2023) |

Lawrence Sullivan Ross | |

|---|---|

President of the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas | |

| In office January 20, 1891 – January 3, 1898 | |

| Preceded by | William Stuart Lorraine Bringhurst (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Roger Haddock Whitlock (Acting) |

| 19th Governor of Texas | |

| In office January 18, 1887 – January 20, 1891 | |

| Lieutenant | Thomas Benton Wheeler |

| Preceded by | John Ireland |

| Succeeded by | Jim Hogg |

| Member of the Texas Senate from the 22nd district | |

| In office January 11, 1881 – January 9, 1883 | |

| Preceded by | John W. Moore |

| Succeeded by | John Alfred Martin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 27, 1838 |

| Died | January 3, 1898 (aged 59) Brazos County, Texas, U.S. |

| Resting place | Oakwood Cemetery, Waco, Texas, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Tinsley (m. 1861) |

Brigadier general (CSA) | |

| Commands | 6th Texas Cavalry Regiment Phifer's Cavalry Brigade Ross's Cavalry Brigade |

| Battles/wars |

|

Lawrence Sullivan "Sul" Ross (September 27, 1838 – January 3, 1898) was the 19th governor of Texas, a Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War, and the 4th president of the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas, now called Texas A&M University.

Ross was raised in the

When Texas seceded from the United States and joined the

Early years

Lawrence Sullivan Ross was born on September 27, 1838,

Shortly after Ross's birth, his parents sold their Iowa property and returned to Missouri to escape Iowa's cold weather.[

In 1845, the family moved to Austin so Ross and his older siblings could attend school.[11] Four years later, they relocated again. By this time, Shapley Ross was well known as a frontiersman, and to coax him to settle in the newly formed community of Waco, the family was given four city lots, exclusive rights to operate a ferry across the Brazos, and the right to buy 80 acres (32 ha) of farmland at US$1 per acre.[12][13] In March 1849, the Ross family built the first house in Waco, a double-log cabin on a bluff overlooking the springs. Ross's sister Kate soon became the first Caucasian child born in Waco.[13]

Eager to further his education, Ross entered the Preparatory Department at Baylor University (then in Independence, Texas) in 1856, despite the fact that he was several years older than most of the other students. He completed the two-year study course in one year.[14][15] Following his graduation, he enrolled at Florence Wesleyan University in Florence, Alabama.[10][16] The Wesleyan faculty originally deemed his mathematics knowledge so lacking, they refused his admittance; the decision was rescinded after a professor agreed to tutor Ross privately in the subject.[16] At Wesleyan, students lived with prominent families instead of congregating in dormitories,[15] thus giving them "daily exposure to good manners and refinement".[17] Ross lived with the family of his tutor.[17]

Wichita Village fight

During the summer of 1858, Ross returned to Texas and journeyed to the Brazos Indian Reserve, where his father served as

Native scouts found about 500 Comanches, including Buffalo Hump, camped outside a

After five hours of fighting, the troops subdued the Comanche resistance.[25][26] Buffalo Hump escaped, but 70 Comanches were killed or mortally wounded, two of them noncombatants.[21][25] Ross's injuries were severe, and for five days, he lay under a tree on the battlefield, unable to be moved.[2][24][26] His wounds became infected, and Ross begged the others to kill him to end his pain. When he was able to travel, he was first carried on a litter suspended between two mules, and then on the shoulders of his men. He recovered fully, but experienced some pain for much of the rest of the year.[24]

In his written report, Van Dorn praised Ross highly. The Dallas Herald printed the report on October 10, and other state newspapers also praised Ross's bravery. General Winfield Scott learned of Ross's role and offered him a direct commission in the Army. Eager to finish his education, Ross declined Scott's offer, and returned to school in Alabama.[26][27]

The following year, Ross graduated from Wesleyan with a Bachelor of Arts and returned to Texas. Once there, he discovered no one had been able to trace the family of the young Caucasian girl rescued during the Wichita Village fight. He adopted the child and named her Lizzie Ross, in honor of his new fiancée,[28] Elizabeth Dorothy Tinsley.[2]

Texas Rangers

Enlistment

In early 1860, Ross enlisted in Captain J. M. Smith's Waco company of

Smith disbanded Ross's company in early September 1860. Within a week, Governor

Battle of Pease River

In late October and November 1860, Comanches led by Peta Nocona conducted numerous raids on various settlements, culminating in the brutal killing of a pregnant woman. On hearing of these incidents, Houston sent several 25-man companies to assist Ross. A citizen's posse had tracked the raiders to their winter village along the Pease River. As the village contained at least 500 warriors and many women and children, the posse returned to the settlements to recruit additional fighters. Ross requested help from the US Army at Camp Cooper, which sent 21 troops.[31]

Immediately after the soldiers arrived on December 11, Ross and 39 Rangers departed for the Comanche village. On December 13, they met the civilian posse, which had grown to 69 members. After several days of travel, the fast pace and poor foraging forced the civilians to stop and rest their horses. All of the US soldiers and 20 of the Rangers continued on. When they neared the village, Charles Goodnight scouted ahead. Hidden from view by a dust storm, he was able to get within 200 yd (180 m) of the village and saw signs that the tribe was preparing to move on. Realizing his own horses were too tired for a long pursuit, Ross resolved to attack immediately, before the civilians were able to rejoin the group. Ross led the Rangers down the ridge, while the soldiers circled around to cut off the Comanche retreat.[32] These "aggressive tactics of carrying the war to the Comanche fireside...ended charges of softness in dealing with the Indians."[33]

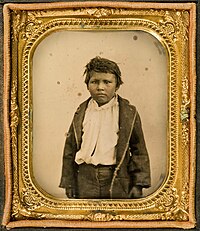

Seven men, women, and children were killed and around seven or more escaped. US soldiers came upon a woman who held a child over her head; the men did not shoot, but instead surrounded and stopped her. Ross admitted to a cousin of Cynthia Ann Parker that he played no hand in helping to rescue Cynthia Ann Parker and her daughter, shown in 1861. The civilian posse arrived at the battleground as the fighting finished. Although they initially congratulated Ross for winning the battle, some of them later complained that Ross had pushed ahead without them so he would not have to share the glory or the spoils of war.[34]

When Cynthia Ann Parker was taken to Ft. Cooper, US command realized the captured woman had blue eyes.

In the aftermath, a nine-year-old Comanche boy found was found hiding alone in the tall grass. Ross took the child with him, naming him Pease. Though Pease was later given the choice to return to his people, he repeatedly declined and was raised by Ross.[40][41]

However, some take issue with this narrative of events. After Ross's death, Nocona's son Quanah Parker maintained his father was not present at the battle, and instead died three or four years later. She identified the man Martinez shot as a Mexican captive, the personal servant of Nocona's wife, Cynthia Ann Parker.[42] In Myth, Memory and Massacre: The Pease River Capture of Cynthia Ann Parker the authors contend most of the material in the 1886 book of James T. Deshields was falsified or exaggerated for political gain. They also offer primary documentation that Peta Nocona was not at the scene, but rather died around 1865, not in December 1860, and that only 15 Comanches were in the camp. Its authors found nine primary accounts of the incident given by Ross, each of them differing from the others.[43]

Resignation

When Ross returned home, Houston asked him to disband the company and form a new company of 83 men, promising to send written directives soon. While Ross was in the process of supervising this reorganization, Houston appointed Captain William C. Dalrymple as his new aide-de-camp with overall command of the Texas Rangers. Dalrymple, unaware of Houston's verbal orders, castigated Ross for disbanding his company. Ross completed the reorganization of the company, then returned to Waco and resigned his commission.[2][3] In his letter of resignation, effective February 1861, Ross informed Houston of his encounter with Dalrymple, and noted he did not believe a Ranger company could be effective if the captain did not report solely to the governor. Houston offered to appoint Ross as an aide-de-camp with the rank of colonel, but Ross refused.[44]

Civil War service

Enlistment/Commissioned Officer

In early 1861 after Texas voted to secede from the United States and join the Confederacy, Ross's brother Peter began recruiting men for a new military company.[45] Ross enlisted in his brother's company as a private,[2][3] and shortly afterwards, Governor Edward Clark requested he instead proceed immediately to the Indian Territory to negotiate treaties with the Five Civilized Tribes, so they would not help the Union Army. One week after his May 28 wedding to Lizzie Tinsley, Ross set out for the Indian Territory.[45] Upon reaching the Washita Agency, he discovered the Confederate commissioners had already signed a preliminary treaty with the tribes.[46][47]

Ross returned home for several months. In the middle of August, he departed, with his company, for Missouri, leaving his wife with her parents. On September 7, his group became Company G of Stone's Regiment, later known as the Sixth Texas Cavalry.[2] The other men elected Ross as the major for the regiment.[48] Twice in November 1861, Ross was chosen by General McCulloch, with whom he had served in the Texas Rangers, to lead a scouting force near Springfield, Missouri. Both times, Ross successfully slipped behind the Union Army lines, gathered information, and retreated before being caught. After completing the missions, he was granted a 60-day leave and returned home to visit his wife.[49]

In early 1862, Ross returned to duty. By late February, 500 troops and he were assigned to raid the Union Army. He led the group 70 mi (110 km) behind the enemy lines, to Keetsville (now Washburn), Missouri, where they gathered intelligence, destroyed several wagonloads of commissary supplies, captured 60 horses and mules, and took 11 prisoners.[49] The following month, the regiment was assigned to Earl Van Dorn, now a major general, with whom Ross had served during the battle at the Wichita Village. Under Van Dorn, the group suffered a defeat at the Battle of Pea Ridge; Ross attributed their loss solely to Van Dorn, and blamed him for overmarching and underfeeding his troops, and for failing to properly coordinate the plan of attack.[50] In April, the group was sent to Des Arc, Arkansas. Because of the scarcity of forage, Ross's cavalry troop was ordered to dismount and send their horses back to Texas. The unit, now on foot, traveled to Memphis, Tennessee, arriving two weeks after the Battle of Shiloh.[51] Ross soon caught a bad cold accompanied by a lingering fever, and was extremely ill for eight weeks. By the time he considered himself cured, his weight had dwindled to only 125 lb (57 kg).[52]

Over Ross's protests, the men of the Sixth Regiment elected him colonel in 1862.

While still afoot, Ross and his men participated in the Battle of Corinth. Under Ross's command, his Texans twice captured Union guns at Battery Robinett. They were forced to retreat from their position each time as reinforcements failed to arrive. During the battle, Ross, who had acquired a horse, was bucked off, leading his men to believe he had been killed. He was actually unharmed.[54] The Confederate Army retreated from the battle and found themselves facing more Union troops at Hatchie's Bridge. Ross led 700 riflemen to engage the Union troops. For three hours, his men held off 7,000 Union troops, repelling three major Union attacks.[55]

The Sixth Cavalry's horses arrived soon after the battle, and the regiment was transferred to the cavalry brigade of Colonel William H. "Red" Jackson. Ross was permitted to take a few weeks leave in November 1862 to visit his wife, and returned to his regiment in mid-January 1863.[56] Several months later, his unit participated in the Battle of Thompson's Station.[57] In July, Major General Stephen D. Lee created a new brigade with Ross at the helm, consisting of Ross's regiment and Colonel Richard A. Pinson's First Mississippi Cavalry. Near the same time, Ross received word that his first child had died, possibly stillborn.[58]

Ross fell ill again in September 1863. From September 27 through March 1864, he suffered recurring attacks of fever and chills every three days, symptomatic of tertiary

In March 1864, Ross's brigade fought against African American soldiers for the first time in the Battle of Yazoo City. After bitter fighting, the Confederates were victorious. During the surrender negotiations, the Union officer accused the Texans of murdering several captured African American soldiers. Ross claimed two of his men had likewise been killed after surrendering to Union troops.[63]

Beginning in May, the brigade endured 112 consecutive days of skirmishes, comprising 86 separate clashes with the Union forces. Though most of the skirmishes were small, by the end of the period, injuries and desertion had cut the regiment's strength by 25%.[61][63] Ross was captured in late July at the Battle of Brown's Mill, but was quickly rescued by a successful Confederate cavalry counterattack.[63]

Their last major military campaign was the

Surrender

By the time Ross began a 90-day furlough on March 13, 1865, he had participated in 135 engagements with Union troops[2][3] and his horse had been shot out from under him five times, yet he had escaped serious injury.[65] With his leave approved, Ross hurried home to Texas to visit the wife he had not seen in two years. While at home, the Confederate Army began its surrender. He had not rejoined his regiment when it surrendered in Jackson, Mississippi, on May 14, 1865.[2][66] Because he was not present at the surrender, Ross did not receive a parole protecting him from arrest. As a Confederate Army officer over the rank of colonel, Ross was also exempted from President Andrew Johnson's amnesty proclamation of May 29, 1865. To prevent his arrest and the confiscation of his property, on August 4, 1865, Ross applied for a special pardon. President Johnson personally approved Ross's application on October 22, 1866, but Ross did not receive and formally accept the pardon until July 1867.[67]

Farming and early public service

When the Civil War ended, Ross was just 26 years old. He owned 160 acres (65 ha) of farmland along the South Bosque River west of Waco, and 5.41 acres (2.19 ha) in town. For the first time, his wife and he were able to establish their own home. They expanded their family, having eight children over the next 17 years.[68]

Despite his federal pardon for being a Confederate general, Ross was disqualified from voting and serving as a juror by the first

Reconstruction did not harm Ross's fortune, and with hard work, he soon prospered. Shortly after the war ended, he bought 20 acres (8.1 ha) of land in town from his parents for $1,500. By May 1869, he had purchased an additional 40 acres (16 ha) of farmland for $400, and the following year, his wife inherited 186 acres (75 ha) of farmland from the estate of her father. Ross continued to buy land, and by the end of 1875, he owned over 1,000 acres (400 ha) of farmland.[70] Besides farming, Ross and his brother Peter also raised Shorthorn cattle. The two led several trail drives to New Orleans. The combined farming and ranching incomes left Ross wealthy enough to build a house in the Waco city limits and to send his children to private school.[71]

By 1873, Reconstruction in Texas was coming to an end.[72] In December, Ross was elected sheriff of McLennan County, "without campaigning or other solicitation".[2][73] Ross promptly named his brother Peter a deputy, and within two years, they had arrested over 700 outlaws.[73] In 1874, Ross helped establish the Sheriff's Association of Texas. After various state newspapers publicized the event, sheriffs representing 65 Texas counties met in Corsicana in August 1874.[74] Ross became one of a committee of three assigned to draft resolutions for the convention. They asked for greater pay for sheriffs in certain circumstances, condemned the spirit of mob law, and proposed that state law be modified so arresting officers could use force if necessary to "compel the criminal to obey the mandates of the law."[75]

Ross resigned as sheriff in 1875 and was soon elected as a delegate to the

When the convention concluded, Ross returned home and spent the next four years focusing on his farm.[77] In 1880, he became an accidental candidate for the Texas Senate from the 22nd District. The nominating convention deadlocked between two candidates, with neither receiving a two-thirds majority. As a compromise, one of the delegates suggested the group nominate Ross. Although no one asked Ross whether he wanted to run for office, the delegates elected him as their candidate. He agreed to the nomination to spare the trouble and expense of another convention.[2][78]

Ross won the election with a large majority.

Although the Texas Legislature typically meets once every two years, a fire destroyed the state capitol building in November 1881, and Ross was called to serve in a special session in April 1882. The session agreed to build a new capitol building.[89] Near the end of the special session, the Senate passed a reapportionment bill, which reduced Ross's four-year term to only two years. He declined to run again.[2][90]

Governor

Election

As early as 1884, Ross's friends, including Victor M. Rose, the editor of the newspaper in

Ross became the 19th governor of Texas.

Second term

In May 1888, Ross presided over the dedication of the new

During his second term, Ross was forced to intervene in the

In March 1890, the

Ross declined to become the first Texas governor to run for a third term,[2] and left office on January 20, 1891.[3][106] During his four years in office, he vetoed only 10 bills, and issued 861 pardons.[107]

Major legislation

During his time in office, Ross proposed tax reform laws intended to provide for more equitable assessments of property; at that time, people were allowed to assess their own belongings with little oversight. The legislature passed his recommendations,[108] and approved his plan to exert more control over school funds and to require local taxation to support the public schools.[109] He also encouraged the legislature to enact antitrust laws. These were passed March 30, 1889, a full year before the federal government enacted the Sherman Antitrust Act.[110] His reform acts were beneficial for the state, leading Ross to become the only Texas governor to call a special session of the legislature to deal with a treasury surplus.[99]

During his term, the legislature agreed to allow the public to vote on a state constitutional amendment for the prohibition of alcohol. Ross vehemently opposed the measure, saying, "No government ever succeeded in changing the moral convictions of its subjects by force."[111] The amendment was defeated by over 90,000 votes.[111]

When Ross took the governor's oath of office, Texas had only four state-owned charitable institutions—two insane asylums, an institute for the blind, and an institute for the deaf and dumb. By the time he left office, Ross had supervised the opening of a state orphan's home, a state institute for deaf, dumb, and blind black children, and a branch asylum for the insane.[109] He also convinced the legislature to set aside 696 acres (282 ha) near Gatesville for a future open farm reformatory for juvenile offenders.[112]

Ross was the first governor to set aside a day for civic improvements, declaring the third Friday in January to be Arbor Day, when schoolchildren should endeavor to plant trees.[113][114] He also supported the legislature's efforts to purchase the Huddle portrait gallery, a collection of paintings of each governor of Texas. These paintings continue to hang in the rotunda of the Texas State Capitol.[114]

Ross felt strongly that the state should adequately care for its veterans. During his first term, the first Confederate home in Texas was dedicated in Austin. Within two years, the facility had run out of room, so Ross served as chairman of a committee to finance a relocation to a larger facility. By August 1890, the home had collected enough money to move to a larger location.[115]

College president

Arrival

By the late 1880s, rumors abounded of "poor management, student discontent, professorial dissatisfaction, faculty factionalism, disciplinary problems, and campus scandals" at the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas (now Texas A&M University).[116] The public was skeptical of the idea of scientific agriculture[117] and the legislature declined to appropriate money for improvements to the campus because it had little confidence in the school's administrators. The board of directors decided the school, known as Texas AMC, needed to be run by an independent administrative chief rather than the faculty chairman. On July 1, 1890, the board unanimously agreed to offer the new job to the sitting governor and asked Ross to resign his office immediately.[117][118] Ross agreed to consider the offer, as well as several others he had received. An unknown person informed several newspapers that Ross had been asked to become Texas AMC's president, and each of the newspapers editorialized that Ross would be a perfect fit. The college had been founded to teach military and agricultural knowledge, and Ross had demonstrated excellence in the army and as a farmer. His gubernatorial service had honed his administrative skills, and he had always expressed an interest in education.[117][119]

Though Ross was concerned about the appearance of a conflict of interest, as he had appointed many of the board members who had elected him, he announced he would accept the position.[120] As the news of his acceptance spread throughout the state, prospective students flocked to Texas AMC. Many of the men Ross had supervised during the Civil War wanted their sons to study under their former commander, and 500 students attempted to enroll at the beginning of the 1890–1891 school year. Although the facilities were only designed for 250 scholars, 316 students were admitted. When Ross officially took charge of the school on February 2,[121] the campus had no running water, faced a housing shortage, was taught by disgruntled faculty, and many students were running wild.[122]

Improvements

The board of directors named Ross the treasurer of the school, and he posted a $20,000 personal bond "for the faithful performance of his duty".

Enrollment continued to rise, and by the end of his tenure, Ross requested that parents first communicate with his office before sending their sons to the school.[125] The increase in students necessitated an improvement in facilities, and from late 1891 until September 1898, the college spent over $97,000 on improvements and new buildings. This included construction of a mess hall, which could seat 500 diners at once, an infirmary, which included the first indoor toilets on campus, an artesian well, a natatorium, four faculty residences, an electric light plant, an ice works, a laundry, a cold storage room, a slaughterhouse, a gymnasium, a warehouse, and an artillery shed.[126][127] Despite the expenditures on facilities, the school treasury held a surplus in 1893 and 1894. The 1894 financial report credited the surplus to Ross's leadership, and Ross ensured the money was returned to the students in the form of lower fees.[126][127]

Impact on students

Ross made himself accessible to students and participated in school activities whenever possible. Those around him found him "slow to condemn but ready to encourage ... [and they] could not recall hearing Ross use profanity or seeing him visibly angry."[128] Every month, he prepared grade sheets for each student and would often call poorly performing students into his office for a discussion of their difficulties.[127][129] Under his leadership, the military aspect of the college was emphasized. However, he eliminated many practices he considered unnecessary, including marching to and from class, and he reduced the amount of guard time and the number of drills the students were expected to perform.[130]

Although enrollment had always been limited to men, Ross favored coeducation, as he thought the male cadets "would be improved by the elevating influence of the good girls".[131] In 1893, Ethel Hudson, the daughter of a Texas AMC professor, became the first woman to attend classes at the school and helped edit the annual yearbook. She was made an honorary member of the class of 1895. Several years later, her twin sisters became honorary members of the class of 1903, and slowly other daughters of professors were allowed to attend classes.[132]

During Ross's seven-and-one-half-year tenure, many enduring

Personal life and death

Ross was a Freemason and became a master mason at Waco Masonic Lodge #92. In 1947, a masonic lodge was named after him.[134]

Ross continued to be active in veteran's organizations, and in 1893, he became the first commander of the Texas Division of the

In 1894, Ross was appointed to a seat on the Railroad Commission of Texas. While he pondered whether to resign his position and accept the appointment, letters and petitions poured into his office begging him to remain at Texas AMC. He declined the appointment and remained president of the college.[136][137]

Ross had always been an avid hunter, and he embarked on a hunting trip along the Navasota River with his son Neville and several family friends during Christmas vacation in 1897. While hunting, he suffered acute indigestion and a severe chill and decided to go home early while the others continued their sport. He arrived in

Legacy

The morning after Ross's death, the

It has been the lot of few men to be of such great service to Texas as Sul Ross. ... Throughout his life he has been closely connected with the public welfare and ... discharged every duty imposed upon him with diligence, ability, honesty and patriotism. ... He was not a brilliant chieftain in the field, nor was he masterful in the art of politics, but, better than either, he was a well-balanced, well-rounded man from whatever standpoint one might estimate him. In his public relations he exhibited sterling common sense, lofty patriotism, inflexible honesty and withal a character so exalted that he commanded at all times not only the confidence but the affection of the people. ... He leaves a name that will be honored as long as chivalry, devotion to duty and spotless integrity are standards of our civilization and an example which ought to be an inspiration to all young men of Texas who aspire to careers of public usefulness and honorable renown.[143][144]

Within weeks of Ross's death, former cadets at Texas AMC began gathering funds for a monument. In 1917, the state appropriated $10,000 for the monument, and two years later, a 10-ft (3 m) bronze statue of Ross, sculpted by

At the same time they appropriated money for the statue, the legislature established the Sul Ross Normal College, now Sul Ross State University in Alpine, Texas.[145] The college opened for classes in June 1920.[144][147]

See also

References

- ^ LCCN 19016834. Retrieved November 3, 2023 – via Texas Legislative Library.

L. S. Ross' father was S. P. Ross, who immigrated to Texas in 1839. He will ever live in Texas history as the killer of "Big Foot," the Comanche chief. Following the death of this dreaded chief, was the sleepless and effective crusade against the rapacious and treacherous tribes of the Comanche and Kiowa Indians. He was the leader of the pioneers who destroyed their power to do evil, and who will ever be held in grateful memory by Texans.

Governor Ross was born at Benton's Post, Iowa, in the year 1838, and came to Texas with his father. His mind familiarized with his father's recitals of Indian warfare, and his heart was inspired to vigilance and action to that foe wherever occasion demanded, and well he did execute the inborn mandate, when mounting his war-steed, with sword and rifle in hand, he marshaled his command against the foe of his brave sire. This was an inherited antagonism. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Benner, Judith, "Ross, Lawrence Sullivan", The Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, retrieved March 3, 2015

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ross Family Papers, Inclusive: 1846-1931, undated, Bulk: 1861-1864, 1870-1894, undated, Baylor University, December 22, 2014, retrieved January 30, 2022

- ^ a b Daniell, Lewis E. (1889). Personnel of the Texas State Government, with sketches of Distinguished Texans embracing the Executive and Staff, Heads of the Departments, United States Senators and Representatives, Members of the Twenty-First Legislature (PDF). Austin: Smith, Hicks and Jones, State Printers. p. 7 – via Texas Legislative Library.

Governor L. S. Ross, the citizen Soldier and Statesman, was born at Benton's Post, Iowa, in 1838. From his father's lineage Lawrence Sullivan inherited the strength, energy, and endurance of body and mind so characteristic of the Scot, and he has honored his ancestry as a noble chieftain in war and peace. His mother's ancestry was Germanic. American nobility of head, heart and physique is not derived from a narrow family line, but springs from the broad plain of the people. From the people even princes choose their best support for the respective thrones. We call them governors, presidents, but crown them not. They need no crown, their words and works proclaim the true nobility.

Captain S. P. Ross, the father, settled in Milam County, Texas in 1839, and made his home in Austin in 1846. - ^ Kemp, L. W. (1995). "Ross, Shapley Prince (1811 – 1879)". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Bridges, Ken (August 7, 2021). "Texas History Minute: The story of Lawrence Sullivan 'Sul' Ross". Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c Benner (1983), pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Davis (1989), p. 149.

- ^ a b Sterling (1959), p. 284.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 9.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 10.

- ^ a b Davis (1989), p. 151.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 14–18.

- ^ a b Davis (1989), p. 152.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), p. 19.

- ^ a b Davis (1989), p. 153.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), pp. 21, 23, 25.

- ^ Mayhall (1971), p. 217.

- ^ Utley (1967), p. 130

- ^ a b c d Utley (1967), p. 131

- ^ a b c Benner (1983), pp. 26–29.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 155.

- ^ ISBN 0-87338-505-5)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b Mayhall (1971), p. 218.

- ^ a b c Benner (1983), pp. 30–33.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 157.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 37. Davis (1989), p. 156.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 38, 40, 42.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 47–48.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 49–50.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 50–53. Davis (1989), p. 160.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), p. 57.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), p. 56.

- ^ "Remember the Ladies: White woman in Comanche world". March 20, 2020.

- ISBN 9780312873868.

- ISBN 9780812978889.

- ISBN 9781931725019.

- ^ Hendrickson (1995), p. 113.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 55.

- ^ "One Little Indian Boy". November 26, 2015.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 161.

- ^ Stratton, W.K. (January 2021). "What Happened at Pease River Wasn't a Battle. It Was a Massacre". Texas Monthly. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 58–60.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), pp. 63–64.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 65.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 164.

- ^ Benner (1984), pp. 67–68. Davis (1989), p. 164.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), p. 72. Wooster (2000), p. 213.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 165.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 76.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 115.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 79, 80.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 84–85. Davis (1989), p. 167.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 87.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 88.

- ^ Wooster (2000), p. 214.

- ^ Benner (1983), p 92.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 116.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 93.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), p. 103.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 169.

- ^ a b c Wooster (2000), p. 215.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 108, 109, 111.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 170.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 111.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 116, 117.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 117, 119.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 119.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 120.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 171.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 124.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), p. 126.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 128.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 129.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 131–133

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 140.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), p. 141.

- ^ "Lawrence Sullivan Ross". Texas Legislators: Past & Present. Texas Legislative Reference Library.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 143.

- ^ "Senate Committee on Agricultural Affairs - 17th R.S. (1881)". Texas Legislative Reference Library.

- ^ "Senate Committee on Contingent Expenses - 17th R.S. (1881)". Texas Legislative Reference Library.

- ^ "Senate Committee on Enrolled Bills - 17th R.S. (1881)". Texas Legislative Reference Library.

- ^ "Senate Committee on Finance - 17th R.S. (1881)". Texas Legislative Reference Library.

- ^ "Senatorial and Representative Districts, Apportionment - 17th R.S. (1881)". Texas Legislative Reference Library.

- ^ "Senate Committee on Statistics of Industries, Public Health, and History of Texas - 17th R.S. (1881)". Texas Legislative Reference Library.

- ^ "Senate Committee on Military Affairs - 17th R.S. (1881)". Texas Legislative Reference Library.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 144.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 146.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 147. Davis (1989), p. 174.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 148–149.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 150.

- ^ a b c Hendrickson (1995), p. 116.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 155.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 157.

- ^ a b c Davis (1989), p. 176.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), pp. 160, 161.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 162.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), p. 166.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), p. 169.

- ^ quoted in Benner (1983), p. 178.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 171–172.

- ^ Davis (1989), pp. 179–182.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 173.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 174–175.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 175, 176.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 179.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 183.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), p. 187.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 192.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), p. 165.

- ^ Davis (1989), p. 183.

- ^ Sterling (1959), p. 283.

- ^ a b Hendrickson (1995), p. 117.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 185.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 199.

- ^ a b c Davis (1989), p. 185.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 200.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 201–203.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 202. Davis (1989), p. 106.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 204.

- ^ a b Ferrell, Christopher (2001), "Ross Elevated College from "Reform School"", The Bryan-College Station Eagle, archived from the original on October 16, 2007, retrieved June 23, 2008

- ^ quoted in Benner (1983), p. 205.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), pp. 206–208.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 218.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), p. 219.

- ^ a b c d e f g Davis (1989), p. 189.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 222.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 223.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 224.

- ^ quoted in Benner (1983), p. 227.

- ^ Kavanagh, Colleen (2001), "Questioning Tradition", The Bryan-College Station Eagle, archived from the original on October 16, 2007, retrieved June 24, 2008

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 225–226.

- ^ Sul Ross, Waco Masonic Lodge, retrieved July 17, 2021

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 230.

- ^ a b Davis (1989), p. 190.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 229.

- ^ Benner (1983), pp. 231–232.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 232.

- ^ Silver Taps, Texas A&M University Traditions Council, archived from the original on December 15, 2007, retrieved December 10, 2007

- ^ a b "Howdy, Mr. President". Texas A&M Foundation. Spring 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ Raines, Caldwell Walton (1902). Year Book for Texas, 1901 (PDF). Austin: Gammel Book Company. pp. 156, 157. Retrieved August 1, 2023 – via Texas Legislative Reference Library.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 235.

- ^ a b c Davis (1989), p. 191.

- ^ a b Benner (1983), p. 233.

- ^ Pierce, Carrie (November 22, 2004), "Have you seen this tradition?", The Battalion, College Station, Texas, archived from the original on September 29, 2007, retrieved August 20, 2007

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 234.

Further reading

- Benner, Judith Ann (1983), Sul Ross, Soldier, Statesman, Educator, ISBN 0-89096-142-5

- Davis, Joe Tom (1989), Legendary Texians, Vol. 4, ISBN 0-89015-669-7

- Eicher, John H.; ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1

- Hendrickson, Kenneth E. Jr. (1995), The Chief of Executives of Texas: From Stephen F. Austin to John B. Connally, Jr., ISBN 0-89096-641-9

- Mayhall, Mildred P. (1971), The Kiowas: Civilization of the American Indian Series; 63 (2 ed.), ISBN 0-8061-0987-4

- Sifakis, Stewart (1988), Who Was Who in the Civil War, New York: Facts On File, ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4

- Sterling, William Warren (1959), Trails and Trials of a Texas Ranger, ISBN 0-8061-1574-2

- Utley, Robert M. (1967), Frontiersmen in Blue: The United States Army and the Indian, 1848-1865, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-9550-6

- ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9

- Wooster, Ralph A. (2000), Lone Star Generals in Gray, ISBN 1-57168-325-9