Leningrad–Novgorod offensive

| Leningrad–Novgorod offensive | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||||

Soviet machine-gunners near Detskoye Selo railway station in Pushkin, January 21 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

(Until February 1) (From February 1) |

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

Army Group North: 44 infantry divisions [2] |

Leningrad Front Volkhov Front 2nd Baltic Front Baltic Fleet: 57 divisions | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

500,000 men 2,389 artillery pieces 146 tanks 140 aircraft[2] |

822,000 men and women 4,600 artillery pieces 550 tanks 653 aircraft[2] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

24,739 dead and missing[3] 46,912 wounded[3] Total: 71,651 casualties (per German military medical reports)[3] |

76,686 dead and missing, 237,267 wounded[4] Total: 313,953 casualties[4] | ||||||||

The Leningrad–Novgorod strategic offensive was a strategic offensive during World War II. It was launched by the

The Germans had suffered nearly 72,000 casualties, lost 85 artillery pieces ranging in caliber from 15 cm to 40 cm, and were pushed back between 60 and 100 kilometers from Leningrad to the

Background

After

Preparations

Soviet

The Baltic Fleet had been assigned the task of transporting the Second Shock Army under the command of Ivan Fedyuninsky over Lake Ladoga to Oranienbaum. From November 5, 1943 onwards, the Fleet transported 30,000 troops, 47 tanks, 400 artillery pieces, 1,400 trucks and 10,000 tons of ammunition and supplies from the wharves at the Leningrad factories, Kanat and the naval base at Lisy Nos to Oranienbaum.[10] After Lake Ladoga froze, another 22,000 men, 800 trucks, 140 tanks and 380 guns were sent overland to the jump-off point.[10] When the shipments were complete, the artillery was positioned along the entire length of the Leningrad, Second Baltic and Volkhov fronts at a concentration of 200 guns per kilometer, including 21,600 standard artillery pieces, 1,500 Katyusha rocket guns, and 600 anti-aircraft guns.[10] 1,500 planes were also obtained from the Baltic Fleet and from installations around Leningrad.[10][11] The total number of Soviet personnel prepared for action was 1,241,000, against the 741,000 German troops.[12] A final meeting took place on January 11 in Smolny.[13] General Govorov, the top Soviet commander on the Leningrad Front, had listed his priorities. In order to open up southeastward and eastward main railroad lines from Leningrad, Soviet troops would have to occupy Gatchina, from which they could retake Mga, the minor city and rail station whose capture in 1941 had closed the last railroad route into Leningrad. Govorov positioned his troops accordingly.[13]

German

The situation of the German Army Group North at the end of 1943 had deteriorated to a critical point. The

The fate of Army Group North turned for the worse in the new year, for

Combat activity

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

Krasnoye Selo–Ropsha offensive: 14–31 January 1944

In the late hours of January 13, 1944, long-range bombers from the Baltic Fleet attacked the main German command points on the defensive line. On January 14, troops from both the Oranienbaum foothold and Volkhov Front attacked, followed the next day by troops of the

Novgorod–Luga offensive : 14 January – 15 February 1944

On 14 January Soviet troops of the Volkhov Front launched an offensive from the Novgorod area towards Luga against a part of the 18th German Army. The aim was freeing the October Railway and encircling, together with the troops of the Leningrad Front, the main forces of the 18th Army in the Luga region.

The offensive did not develop as rapidly as planned before the operation. The German 18th Army suffered a heavy defeat, but still wasn't destroyed and retained a significant part of its combat potential, which prevented the Soviet troops in the spring of 1944 to break through the Panther–Wotan line and begin the liberation of the Baltics. One of the reasons for this development was the lack of coordination between the 2nd Baltic Front and the Volkhov Front, which allowed the German command to move significant forces from the 16th Army to the Luga area.

By February 15, the troops of the Volkhov Front, as well as the 42nd and 67th Army of the Leningrad Front, reached Lake Peipus, having pushed the enemy 50–120 kilometers to the West. In total 779 cities and settlements were liberated, including Novgorod, Luga, Batetsky, Oredezh, Mga, Tosno, Lyuban and Chudovo. The restoration of control over the strategically important railways, especially Kirov and October, was of great importance.

Staraya Russa – Novorzhev Offensive : 18 February – 1 March 1944

On 18 February, Soviet troops of the 2nd Baltic Front, carried out this operation in cooperation with part of the Leningrad Front against the German 16th Army of Army Group "North" with the aim of liberating the area southwest of Lake Ilmen and creating the conditions for further offensives.

As a result of the operation, the Soviet troops, pursuing the retreating enemy, advanced up to 180 kilometers to the West, liberating many cities and towns, including Staraya Russa, Novorzhev, Dno and Putoshka.

Kingisepp–Gdov Offensive : 1 February – 1 March 1944

Overview

|

|

|

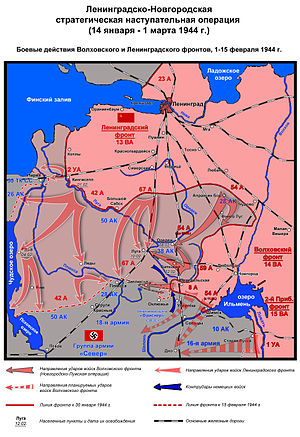

| Position of the armies before the operation and plan of attack | Operations between 14 and 31 January 1944. | Operations between 1–15 February 1944 |

Aftermath

In Soviet propaganda, this offensive was listed as one of Stalin's ten blows.

References

- ^ Most of modern Novgorod Oblast and parts of Pskov Oblast belonged to Leningrad Oblast at the time.

- ^ a b c Glantz 2002, p. 329.

- ^ a b c "Heeresarzt 10-Day Casualty Reports per Army/Army Group, 1944". Human Losses in World War II. German Statistics and Documents. Archived from the original on 2012-10-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Glantz & House 1995, p. 298.

- ^ a b "Siege of Leningrad". Second World War History Online. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Krivosheev, Grigori et al., p. 315

- ^ Krivosheev, Grigori et al., p. 317

- ^ a b A.A. Grechko. Geschichte des Zweiten Weltkrieges (History of World War II. In German).

- ^ a b c d e Salisbury, p. 560

- ^ a b c d Salisbury, p. 561

- ^ Гречанюк, Дмитриев & Корниенко 1990.

- ^ Salisbury, p. 561–562

- ^ a b c d Salisbury, p. 562

- ^ a b Kenneth W. Estes A European Anabasis — Western European Volunteers in the German Army and SS, 1940-1945. Chapter 5. "Despair and Fanaticism, 1944–45" Columbia University Press

- ^ a b Salisbury, p. 564

- ^ Salisbury, p. 565

- ^ a b Salisbury, p. 566

Bibliography

- ISBN 0-7006-2120-2.

- ISBN 0-7006-1208-4.

- ISBN 0-306-81298-3.

- Гречанюк, Н.М.; Дмитриев, В.И.; Корниенко, А.И. (1990). Дважды, Краснознаменный Балтийский Флот (Baltic Fleet). Воениздат.

- Кривошеев, Григорий; Андроников, Владимир; Буриков, Петр (2010-03-25). Россия и СССР в войнах XX века: Книга Потерь. Moscow, Russia: Вече.