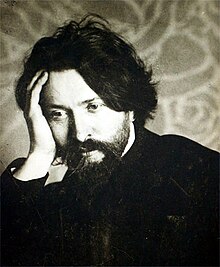

Leo Sirota

Leo Sirota | |

|---|---|

| Лео Григорьевич Сирота | |

Kamenets-Podolsky, Podolia Governorate, Russian Empire (disputed) | |

| Died | February 25, 1965 (aged 79) New York City, US |

| Resting place | Ferncliff Cemetery |

| Nationality |

|

| Other names | Leiba Girshovich |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1893–1965 |

| Spouse |

Augustine "Gisa" Horenstein

(m. 1920) |

| Children | Beate Sirota Gordon |

| Relatives | Jascha Horenstein (brother-in-law) |

Leo Grigoryevich Sirota

Settling in Vienna, Sirota was celebrated by the city's society. He also became one of Busoni's favorite pupils and was later treated by him as a colleague. World War I disrupted his international career. He met and befriended Jascha Horenstein during this period, eventually marrying his sister. After the war, his career resumed, and was acclaimed across Europe.

After his second tour of the

He returned to musical life after the war, emigrating to the United States, which became his final home. After briefly living in New York City, he accepted the role as head of the piano department at the St. Louis Institute of Music, and settled with his wife in the suburb of Clayton. In late 1963, Sirota returned to Japan for what became his final performances there; the trip was widely reported on in the Japanese press. He died in New York City in 1965.

Biography

Youth

Sources conflict on where Sirota was born in the

Sirota began studying piano at age 5 with a pianist who was boarding with his family, Michael Wexler. Sirota's pianistic skill developed rapidly. Administrators at his school regularly called upon him to play for visiting dignitaries.

At the age of 10 Sirota embarked upon his first Russian tour, during which he played for

In 1899, Sirota was appointed a répétiteur for the Kiev Civic Opera, where he also accompanied visiting singers in recitals, including Feodor Chaliapin.[7][4]

The rise of anti-Semitic violence in Russia at the beginning of the 20th century convinced Sirota to consider emigration. His brothers had already preceded him by emigrating to Warsaw and Paris.[9] Sirota emigrated to Vienna in 1904.[8]

Vienna and studies with Busoni

Sirota's talent, personality, and appearance helped him quickly gain acceptance into Viennese musical society of the time, which opened professional and social connections for him. Women were particularly drawn to him; one admirer bequeathed to him an apartment.[8] At first he refrained from using his letter of recommendation to Busoni, choosing instead to first audition for Paderewski, Josef Hofmann and Leopold Godowsky. He auditioned for Busoni after and chose him as a teacher. When Sirota presented his letter of recommendation from Glazunov, Busoni replied, "What need is there for this? I have heard you play!"[10] While studying with Busoni, Sirota also enrolled as a philosophy student at the University of Vienna using the name Leiba Girshovich.[3]

In 1905, Sirota entered the Anton Rubinstein Competition in Paris, but failed to win a prize. His fellow contestants were Otto Klemperer, Béla Bartók, Leonid Kreutzer, and Wilhelm Backhaus; the last two winning fourth and first prizes respectively. Sirota decided not to return to live in Russia after the competition and, instead, settle in Vienna.[11]

Busoni regarded Sirota as one of his best students.[12] He dedicated a copy of his Elegies to him after hearing him perform Franz Liszt's Réminiscences de Don Juan. "After that masterful piece of playing, I don't wish to hear anyone else today", he told Sirota.[13] Sirota was proud that Busoni had referred to him as a "colleague" in the inscription.[14] Busoni later also dedicated his Giga, Bolero e Variazione: Studie nach Mozart to Sirota.[13]

In 1910, Sirota won Busoni's permission to perform the Viennese premiere of his Piano Concerto at a concert with the Tonkünstler Orchestra. Sirota later recalled his anticipation for he concert he regarded as his "true debut":

I intended to make my debut in Vienna by playing in a concert with a famous contemporary conductor. Busoni was the finest of conductors as well as my former teacher and he was popular throughout Europe. That was why I persuaded him to come to Vienna. I wrote to him in haste and asked him to allow me to play his Piano Concerto, which had not yet been played in Vienna [...] Busoni wrote me back very promptly and made all the necessary arrangements. He also revealed to me ideas he had been thinking over. That was in September and the concert was held in [December]. I practiced this piece eight hours a day six days a week and I took the stage with no rehearsal.[15]

The concert took place at the Great Hall of the Musikverein on December 13 and was conducted by Busoni. Arnold Schoenberg was among those who were in attendance.[15] The performance was a public and critical success. Busoni predicted a great future for his pupil.[13] A local music critic wrote:

A fresh, young, and extraordinarily talented pianist, Leo Sirota paid tribute to his teacher Ferrucio Busoni [...] [W]e were extremely impressed by the keen insight and instruction methods of Busoni as a teacher. Sirota is a serious artist. He has awesome technique, a soft key touch, unbelievably sustained [phrasing], and great affection for the musical works he played. [...] The tumultuous applause seemed to be directed towards Sirota the pianist rather than Busoni the composer/conductor [...][16]

Sirota's success at the concert was also reported on internationally. Ethel Burket, a correspondent for the Nebraska State Journal, wrote about the reception that met Sirota's performance of Busoni's "perfectly stupendous" concerto:

At the end such a pandemonium broke forth and the whole audience seemed carried away to the point of madness. Such clapping, yelling, and stamping I have never heard. Finally the lights were turned out and after many minutes the crowd began to disperse.[17]

Sirota later said of Busoni:

Busoni didn't mention technical issues: he left such things in his student's hands. Nor did he compel them to employ special practice methods for particular composers, encouraging them to become musically mature through their own experience. He gave them very brief advice with new approaches to various styles and interpretations.[18]

Sirota also praised Busoni's generosity with gifted students with limited financial means, whom he would teach without charge.[19]

1910 Anton Rubinstein Competition

Later in 1910, Sirota returned to Russia to participate in the Anton Rubinstein Competition, which was being held in St. Petersburg that year. There was controversy ahead of the event because of a Russian law prohibiting people of Jewish descent from staying more than 24 hours in St. Petersburg. Despite a petition from local musicians headed by Glazunov, the government refused to rescind the law. Exceptions were made for those who, like Sirota, had earned the title of "Free Artist" upon completion of their studies in Russia.[20]

Along with Sirota, participating pianists included Lev Pouishnoff, Edwin Fischer, Alfred Hoehn, and Arthur Rubinstein; the latter recalled in his memoirs:

After Fischer, I heard Sirota, [Pouishnoff], and an Englishman. They depressed me—they played too well. All [of them] had the kind of technical polish which I never possessed. And they never missed a note, the devils.[21]

Hoehn was awarded the first prize; Sirota did not place among the winners. His friendship with Arthur Rubinstein, which began at the competition, endured for the rest of their lives.[22]

World War I

Although as a Russian citizen Sirota was exempt from service in the Austro-Hungarian Armed Forces, his career was still disrupted when World War I began in July 1914.[23] He was permitted to perform in public during the war, despite being the citizen of an enemy nation.[24]

During the war Sirota met Jascha Horenstein, a fellow immigrant from Kiev who was also a student at the University of Vienna. Horenstein began to study with Sirota, whom he invited to play with the pickup orchestra he organized on Sundays. The two became lifelong friends.[24] Horenstein invited his 23-year-old sister Augustine, known informally as Gisa, to hear Sirota play at a forthcoming concert. She was so moved by Sirota's performance and appearance that she forgot to applaud. Afterwards she was introduced to him by her brother. She began to study piano with Sirota. Their relationship developed into an affair, during which he proposed marriage to her; she refused as she was married with a son.[25]

European success

The end of the war in 1918 had significant personal consequences for Sirota. Although he identified strongly with Russia and its culture, he was disappointed by the outcome of the October Revolution and felt that he no longer had a homeland to return to.[26][27] He was also unhappy with the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy in Austria.[27] In spite of these and other postwar difficulties, Sirota made a successful return to an international performing career.[28] He also made use of his experience as a répétiteur and facility with modern music during summer 1919, when Lotte Lehmann asked him to help her prepare the role of the Dyer's Wife in Richard Strauss' new opera Die Frau ohne Schatten:[29]

I was the Dyer's Wife and found her an enthralling task. [...] I tried to study it by myself, but was glad when Leo Sirota, the pianist, took pity on me and sacrificed many hours of his holiday to coaching me in the extraordinarily difficult part of which Strauss himself had said jokingly to me that he scarcely believed it would be learned.[30]

Throughout these years Sirota maintained intermittent contact with Gisa Horenstein, who still refused to divorce her then husband. Busoni interceded and spoke to her, speaking very favorably of Sirota's personal qualities. She finally agreed to a divorce, leaving her son in the custody of her husband. In 1920, Sirota and Gisa were married.[31] "You're married to a great artist", Busoni told her after the wedding ceremony. "Please take good care of him."[32] In 1923, their only daughter Beate Sirota Gordon was born.[33] By the end of the 1920s, the Sirotas had become naturalized Austrian citizens.[26]

In 1921, Sirota was invited to Berlin by Serge Koussevitzky to play concertos by Anton Rubinstein and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. His successful performances resulted in positive reviews from local critics. One wrote that Sirota's "virtuosity, passionate temperament, and engaging personality" had "literally taken Berlin by storm"; another called him a "master" and wondered in his review, "Do Russians have a monopoly on pianism?" Sirota's success in Berlin led to engagements across Europe; in concerts conducted by Busoni, Koussevitzky, Horenstein, Carl Nielsen, and Bruno Walter.[28] Further positive reviews followed, with one critic likening his playing to that of "Liszt resurrected from the dead".[34] The Neue Freie Presse called him the "glorious exponent of the Busoni school".[35]

Busoni's death in 1924 was a shock to Sirota. In an essay published in 1958, Sirota praised Busoni's character and musicianship, as well as his championing of new music:

In addition to teaching, playing, and composing, Busoni made important contributions to the development of modern music. He was one of the first to recognize the importance of Schoenberg and Bartók, and invariably included works by these and other contemporaries in his annual concerts in Berlin. He was so vitally concerned with young artists that he set aside daily periods in which he was available for consultation, advice, and encouragement. Ferruccio Busoni's death at the age of fifty-eight (in 1924), was a blow not only to all of those who today remember him with great esteem and deep affection, but to the entire world of music which will be forever indebted to him.[36]

Sirota himself performed new music and, together with his friend Eduard Steuermann, regularly performed Schoenberg's piano works.[35]

As the 1920s progressed Sirota began having increased contacts with Soviet diplomats and musicians, including Adolph Joffe. During late 1926 and early 1927 Sirota toured the Soviet Union, playing in Moscow, Kharkov, and Baku. Upon his return Sirota reported to a German newspaper his positive impressions, adding that he was "quite willing to make a second visit".[37] In 1928 he returned for a second tour, this time performing with Egon Petri. The tour concluded in Vladivostok, from where Sirota embarked on a solo tour of Manchuria.[38]

First trip to Japan

Sirota arrived in Harbin—which in 1928 had large expatriate communities of White Russians, Soviets, and Japanese—and checked into the Modern Hotel. There he told waiting journalists:

After passing through Siberia, Harbin seems amazingly like Paris. I'm enjoying its culture and elegantly dressed people.[39]

The circumstances of how Sirota made an unscheduled trip to Japan from Manchuria are disputed. According to his daughter, after a concert Sirota was visited at his hotel by

Everybody said that Sirota had come, but I couldn't believe that the famous Sirota was actually in Japan, so I was truly astonished.[42]

Yamada, in cooperation with the

For [Sirota] there is no technical difficulty whatsoever; on his keyboard nothing is impossible. His advent is truly summed up in a single word: "marvelous". I think Sirota is the sum of all piano performers of the past and his is a superhuman sort of existence which represents the summit of piano playing at the present time.[42]

On November 15, Sirota made his Japanese public debut, attracting overflow crowds to Tokyo's Asahi Hall despite heavy rain that day. According to Yamamoto Takashi, the public's excitement for Sirota's debut dovetailed with the celebratory mood in Japan at the time over the succession of the

In a single stroke he literally conquered the music world of Tokyo. No pianist before him has ever done this. He is indeed a fortunate man to have received such an enthusiastic welcome from a select audience who really understood the music.[42]

Altogether Sirota played 16 concerts in the Japanese leg of his tour, which ended with a concert on December 21 at the Nippon Seinenkan. That performance was the first he chose to play on a Yamaha piano, then known as Nippon Gakki. His choice, unprecedented for visiting Western artists at the time, resulted in Nippon Gakki widely advertising his endorsement; he is credited with helping to popularize Yamaha pianos.[43] At the end of the tour, the Japanese press referred to Sirota as a "god of the piano".[44]

When Sirota returned to Vienna, he reported to his family that Japan "went crazy", treated him "as if he were a king", and that it was going to be a "great country one day".[40] He also described to them his feelings on seeing Mount Fuji, whose shape he depicted with his hands, for the first time through his train window:

You'd never forget it—it's superb. I hope you two will see it someday.[40]

Sirota also informed his family that Yamada had offered him a teaching position at the

Interwar years in Japan

On the way to Japan, Sirota befriended

The deteriorating political situation in Europe, particularly the strong showing of the

Sirota was the most popular pianist in Japan during the period before the

During the 1930s Sirota performed chamber music frequently with Kishi, Pollak, Alexander Mogilevsky, and Ono Anna. The latter two regularly requested Sirota to partner their students in recital; among them were Iwamoto Mari and Tsuji Hisako, accompanying both on their public debuts.[59] In 1931, Sirota, Pollak, and cellist Heinrich Werkmeister founded the Sirota Trio; they performed at the Rokumeikan and became the most prominent Japanese chamber music group of their time.[60]

In 1936, while on his final European tour before World War II, Sirota told journalists:

When I visited [Japan] for the first time, I didn't expect things to be of a particularly high level, but I have had some unbelievably wonderful surprises there. [...] Tokyo has advanced so much in the last 50 years or so that it has become one of the music centers of the world. [...] The level of music in Tokyo is as high as that of Vienna, Paris, or Berlin. [...] Cultural life in Japan is surprisingly rich and of high quality.[61]

Sirota lived comfortably in Japan and integrated into its society. He was also relieved that anti-Semitism was a very fringe notion in early 1930s Japan, stating to Polish journalists that it had "absolutely no Jewish issue".[62] His daughter later said, "I am quite certain that my dad was very happy in Japan".[63]

Japan and rising international tensions

On September 18, 1931, the

Early Shōwa-era Japan treated its residents of Jewish descent equally as other foreign residents.[67] Sirota himself commented to the European press that Japan was "generous" to its Jewish residents and that the country "would never discriminate against them or restrict their freedom".[68] This began to change in March 1938 with the Anschluss, which resulted in Sirota's Austrian citizenship becoming German. In November of the same year, the Japan-Germany Cultural Agreement (Japanese: 日独文化協定, romanized: Nichidoku Bunka Kyōtei), which commemorated the Anti-Comintern Pact of 1936, was signed. When it was enacted, Germany heavily pressured Japan to dismiss all musicians of Jewish descent from official posts. A German representative at the time told the Japanese press that it was "regrettable that music in Japan is dominated by the Jews".[69] Policy changes that resulted from the agreement included discouraging inviting anymore people of Jewish descent to Japan, excepting those considered "especially useful [...] such as capitalists and technicians".[70] Initially, Japanese musical institutions resisted firing Jewish staff or removing them from concert programs, including Nippon Columbia which refused to purge its catalog of recordings by Sirota and other musicians of Jewish descent.[71] They continued to play in public and teach through the early 1940s.[72]

In spite of these and the goodwill Sirota had developed, he and his family came under scrutiny. His daughter, who attended a German school in Tokyo, was harassed by staff because of her ethnic background. She was also given low marks at the end of the school year in 1936 because she had been overheard to have said that the

Sirota and his wife sailed on the

When the Tatsuta Maru approached San Francisco on July 24, its crew learned that they would not be allowed to dock because of fraught diplomatic tensions between the United States and Japan, as well as an embargo on a shipment of Japanese silk that was aboard. Some passengers who had remained awake around 11:00 p.m. on July 23 noticed that the Tatsuta Maru came to a halt, then reversed course. The next morning, passengers discovered that instead of being in San Francisco Bay, they were beyond any visible shoreline, with the ship traveling in a northwesterly direction away from their intended destination. Panic began to set in among some passengers, who were dissatisfied with the crew's explanations.[77] In response, Sirota performed several impromptu concerts which were reported on across the United States.[78] Sirota later told the San Francisco Examiner that he did it:

[T]o help soothe the passengers. I hope they found temporary forgetfulness in the works of the great masters.[79]

Eventually, on July 30, the passengers aboard the Tatsuta Maru were allowed to disembark in San Francisco.[77]

During his visit to California, Sirota reunited with Erich Wolfgang Korngold, whom he had known back in Vienna. The composer found him and his family accommodations at Eva Le Gallienne's apartment. Sirota's wife and friends attempted to convince him to stay in the United States, warning him that war with Japan was imminent.[75] Although the Los Angeles Times announced in September that Sirota planned to settle in the United States,[80] his daughter said he refused to do so, citing what he had heard through his connections to top Japanese government officials, who had relayed to him that war was unlikely. He also explained that he felt he had to honor his obligations to the Tokyo School of Music and his students.[75]

That same month, he sailed for Japan with his wife, but were forced to disembark in

Sirota's concerts in Hawaii were well received by local audiences and press. George D. Oakley, music critic for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin wrote after Sirota's Hawaiian debut:

Devotees of pure music who attend these concerts usually settle into their chairs prepared to enjoy a pleasant Sunday afternoon's entertainment. With the first bars of the programmed Scarlatti the cognoscenti sat up tense, for the soloist gave immediate notice that those present were in for an afternoon of piano playing which must rank A No. 1. [...] Having thus introduced himself, this pupil of Busoni [...] proceeded to present five Chopin selections in just about as impressive a manner as any critique may desire. There was poetry in his conception, singing quality in the tone, a suborning sweetness in the delicate, intimate passages, and a red-blooded aggressiveness [...] which bespoke the artist of major caliber. Mr. Sirota's sensitivity to the melodic line, so often lost by less qualified performers [...] held his audience engrossed in rapt attention, carried along in a musical experience rarely offered under these circumstances.[88]

The music critic for the

In addition to performing, Sirota was feted by Hawaiian dignitaries, including George Burroughs Torrey and his wife at their home in Kalihi.[90]

Sirota's final Hawaiian concert took place on November 3 at

Wartime

On November 25, 1941, Germany revoked the citizenship of all its Jewish citizens living outside the country. Sirota, who was still aboard the Taiyō Maru at the time, was left stateless. On December 8, Japan began to conduct mass surveillance of its stateless residents.[95]

Extreme nationalists rebuked classical music as a result of the popular animosity against the Allies. The Japanese government maintained its support for classical music; a naval officer, Hiraide Hideo coined the phrase "Music is munitions" (Japanese: 音楽は軍需品なり, romanized: Ongaku wa gunjuhin nari).[96] Official policy towards composers and performers of Jewish descent remained ambiguous until the end of the war; the Japan Symphony Orchestra performed Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 4 as late as January 1945.[97] Sirota's musical activities increased during the first years of the Pacific War. Aside from concertizing and teaching, he also began to share conducting duties with Manfred Gurlitt at the Tokyo Symphony Orchestra.[95] Sirota maintained a busy performing and teaching schedule,[98] playing in public until January 1944, when he appeared on the same Japan Symphony Orchestra program as harpsichordist Eta Harich-Schneider.[99]

In October 1943,[100] the Greater Japan Musical Culture Association, which was jointly run by the Imperial Ministry of Education and Home Ministry, notified its members to avoid playing in public with foreign musicians who were citizens of Allied countries; towards the end of the war, the directive was expanded to citizens of Axis nations.[98] This led to the Tokyo Music School's purging of staff of Jewish descent that same year. The change in policy was so abrupt that when Fujita had to replace Sirota in a performance of Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 5 in Yokohama, she had no time to rehearse or retrieve her concert dress.[101]

When

Karuizawa was a popular summer resort for foreigners before the war.[104] Sirota had a summer house there, but it was not well-equipped for the winter.[105] Sirota explained to a reporter for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in 1947:

It was fine in summers, but [...] those winters! The Japanese furnished us very little fuel and what we had we used in the living room—where the piano was.[106]

Worsening shortages of fuel and food drove Sirota to forage for anything edible in the surrounding areas, as well as find and chop his own firewood. He did this despite his wife's concerns that he could injure his hands.[104] The Swiss diplomatic legation successfully negotiated with the Japanese government for allocations of rations that they would distribute to Europeans in Karuizawa.[103] Local Japanese were hesitant to provide food to foreign residents as many feared being scrutinized by the Tokkō, but some helped him surreptitiously.[107] Sirota recalled one such episode in a 1954 interview with Theatre Arts:

I soon became resigned to [being regularly visited by the Tokkō] and I was only mildly annoyed when two young government agents appeared at the door. Never having seen them before, I assumed they were new in the district. They came in, politely introduced themselves, and then instead of proceeding with the usual questioning, they asked me to play the "Moonlight Sonata" to them. I was quite taken aback—but then one does not argue with the [Tokkō], so I sat down at the piano and played. When I had finished, they applauded enthusiastically and asked for an encore [...] Again I obliged, whereupon they thanked me, rose silently, and left me to puzzled speculation. The next morning brought a new surprise: I found a large box on my doorstep, which, when unpacked, yielded a bottle of wine, a large chicken, some fruit, chocolate, and cake—all rare delicacies during the war. An attached card read: "Please forgive us for having deceived you. You see, we are not [Tokkō] at all, but students who have just been drafted for overseas duty. We wanted so much to hear your wonderful playing once more, before leaving the country, and we couldn't think of a better way but to disguise ourselves as [Tokkō]".[108]

By early 1945, the number of evacuees in Karuizawa, both Japanese and foreign nationals, increased to the point that housing became scarce.[109] The Sirotas spared what supplies they could to friends who needed them. They also shared their home with new evacuees, including the painter Varvara Bubnova, for whom they later found a room.[110] Although forbidden from teaching Japanese students,[107] Sirota continued to do so covertly, as well as practice three hours a day. His students provided him with supplies throughout the war.[56] In order to earn more money, his wife taught piano to families of Spanish and Swiss diplomats.[107]

On May 25, Nagaoka, one of Sirota's best pupils, was killed in the Yamanote Air Raid. His home in Nogizaka was also destroyed that night, but his personal papers had been kept safe elsewhere by his wife.[111] On July 31, Sirota was informed by the Tokkō that he was to appear at the local precinct for questioning on August 6. That day coincided with the atomic bombing of Hiroshima; a Swiss diplomat privately disclosed the news to Sirota, adding that the end of the war was imminent. Sirota chose to ignore the Tokkō's request for inquiry. On August 15, Japan accepted the terms of the Potsdam Declaration and surrendered unconditionally; later in the day, Sirota and his wife celebrated the event with a party at their home.[112][109]

Immediate postwar

Sirota and his wife survived the war, but were left in precarious health.[113] On November 17, 1945, Sirota performed his first postwar concert: a program of music by Busoni, Franz Liszt, and Carl Maria von Weber, conducted by Joseph Rosenstock.[114] Earlier that month in Karuizawa, Sirota met Anthony Hecht, who was working in Japan as a writer for Stars and Stripes:

An even better friend of mine [than Rosenstock] is a chap named Sirota. Magnificent pianist. Ranks, so they tell me, among the six best in the world. I must admit I've never heard of him, but I heard him play Chopin, Liszt, and Glinka the other night, and insofar as I am able to discern, he is incomparable. [...] He is a good friend of Rudolf Serkin, Egon Petri, and a few others whose names I've forgotten.[115]

Hecht arranged for Sirota to perform a recital at the base he was stationed at in Kumagaya. Dissatisfied with the quality of pianos at the base, Hecht procured a grand piano from a local brothel.[116]

The Sirotas lost contact with their daughter Beate during the war. Cut off from her parents' support, she started to work in 1942 at a

Soon after, the Sirotas returned to Tokyo. Finding accommodations was difficult as bombing destroyed much of the city's housing. What was left was reserved for Allied personnel. A former student, Kaneko Shigeko, provided the Sirotas with a pair of rooms in her home.[113]

At Tokyo Music School, a new administrations enacted reforms that were controversial with faculty and students. Pringsheim, who lobbied for Sirota to be rehired by the school, became entangled in administrative politics. Sirota was eventually approached with an offer for reinstatement by the school's new director, but he declined.[123]

By late 1946, Sirota announced his intention to leave Japan for the United States. His pupils were disappointed. Fujita felt not enough was being done to convince Sirota against emigration:

Are we Japanese such an ungrateful nation?[124]

Japan's destruction and economic hardships, changing attitudes towards musical performance, and his daughter's forthcoming marriage were all determinative factors in Sirota's decision. He also felt betrayed by actions taken against him during the war. His daughter later said:

My father loved the Japanese people and he made tremendous efforts for the country. But he really had a hard time in Karuizawa and was very discouraged.[124]

On October 18, 1946, Sirota and his wife boarded the USS Marine Falcon and left Japan.[125]

United States

News reports emerged in January 1946 that Sirota was preparing to move to the United States.[126] After he departed from Japan, he stopped in San Francisco in November,[127] before settling in New York City.[128]

Sirota played his New York debut at

He played them diabolically, at tremendous speed and in the grand manner. Details were not always clear, and overpedaling blurred many passages, but nonetheless this was an impressive exhibition of virtuosity.[133]

In spite of mixed reviews, the Carnegie Hall recital brought Sirota to national attention. With Koussevitzky's help,[130] Sirota was appointed head of the piano department at the St. Louis Institute of Music; the news was announced on September 28, 1947.[134] A local debut recital, free to the public,[135] followed on November 18 at the Sheldon Memorial Auditorium. His public elicited repeated ovations from the audience,[136] but the reaction from critics was muted. Thomas B. Sherman of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch criticized Sirota's program of music that contained "nothing therein that called for the sustained working out of a large design", but related aspects of his playing positively:

Much of Dr. Sirota's performance was of heroic size. He commanded a powerful tone, employed a wide range of dynamics, and made a free use of the sustaining and the damper pedals in obtaining coloristic effects. [...] [He] rode the hurricane of sound in a way that brought an emphatic demonstration of approval from the large audience.[137]

Later recitals garnered more approval from St. Louis critics. A 1949 recital, which included the local premiere of

[Sirota's] exhilarating presentation of three episodes from Stravinsky's Petrushka [...] was an experience not to be forgotten soon. [...] Sirota brought them off with a wonderfully crisp, brilliantly ordered style; the rhythms tense, but elastic, the acrid bouquet intact.[138]

Sirota settled down comfortably in St. Louis, where he kept a balance of teaching and concertizing that was agreeable to him.

Return and farewell to Japan

Sirota's experiences during the Pacific War left him disenchanted with Japan, but he continued to stay in contact with his students, and inquire with them about matters in the country; some of which he learned through his daughter's work at the Japan Society.[149] He also expressed the desire to revisit Japan several times during the 1950s and 1960s,[150] including to Kaneko when she visited St. Louis in December 1961.[151] Upon hearing this, she was galvanized to act. She proposed the idea of a Sirota concert to impresarios in Japan, but was rejected; one dismissed him as a "man of the past". Undeterred, she gathered a 300-member committee[151] that consisted included friends, former students such as Toyomasu Noboru, and Yamada,[152] who was the committee chairman.[151] By then retired and confined to bed because of a stroke, Yamada nevertheless took the initiative and placed an international call to Sirota:

Japan has changed completely. I can't tell you everything on the phone. Many of your students have never forgotten you, so why don't you visit Japan as soon as possible?[153]

Sirota accepted the offer and made preparations for a three-week visit scheduled for the end of 1963.

On November 24, Sirota and his wife arrived to Tokyo aboard a JAL flight.[151] Waiting for him upon arrival were sixty of his former students, as well as friends, government dignitaries, and television journalists.[157] To the press he described the trip as a "sentimental journey".[155] Shortly after arriving, he appeared on a television interview, but found himself unexpectedly answering questions relating to the assassination of John F. Kennedy, which had occurred the day before.[158][n 3]

Sirota's farewell Tokyo recital took place at

The Japanese music world would like to warmly welcome Maestro's visit back to Japan. It is our great pleasure to have an opportunity to show our gratitude and to reward him for his great contributions in the past.[153]

Pringsheim, his old friend and colleague, attended the concert. He later wrote in the Mainichi Shimbun:

After [Sirota's] absence from Japan for the last 16 years, he held only one concert in Hibiya Public Hall, and his fans warmly welcomed this young man in his seventies. Sirota's playing was characterized by absolute clarity and his extremely delicate touch. [...] [I]t was the most beautiful performance I've ever heard in my long life. His program avoided showiness and excessive gorgeousness, but it revealed the artistic wisdom of old age. [...] After the applause, the great artist played an encore. [...] It was a firework show of fantastic bravura, just like the good old days before the war.[159]

A second concert followed at Hibiya Public Hall on December 5. This time, Sirota conducted members of the Japan Philharmonic Orchestra, with former students as soloists. After the concert, he told the press that being recognized for his importance in Japanese musical history and watching his students' performances gave him the "happiest time" in his "long life".[159] He also said that he was proud that young pianists in Japan had reached a level of skill equal to their peers anywhere else in the world and noted that the enrichment of musical culture was comparable to that of the United States.[160]

After the concerts, Sirota met with Yamada at his home; the composer had been physically unable to attend.[161]

When Sirota returned to the United States, he told the press the trip had been like a "wonderful dream", and that "every hour of every day" he was constantly occupied.[157] On December 17, Kaneko and the committee which brought Sirota to Japan published an open letter thanking St. Louis for the trip:

How happy we are to see again our kind teacher, Professor Leo Sirota! [...] We thank you very much for having sent such a great musician. It is a pity that his stay is too short. The name of St. Louis is now familiar with the Japanese because Prof. and Mrs. Sirota's arrival, their visits, and piano recital were reported on television, in newspapers, and

newsreels all over Japan. We hope our friendship between Tokyo and St. Louis will last forever.[162]

Sirota's daughter believed the concerts and journey had allowed him to "make his peace with Japan".[163]

Final illness and death

Sirota performed his final recital in St. Louis in June 1964. Throughout the year, he had been discussing with Fujita and other former students his ideas for a pair of 80th birthday recitals, one in Japan and the other in the United States. His health declined precipitously. In February 1965, he resigned from the St. Louis Institute of Music and went to New York City, where he rented an apartment near his daughter.[164] He died on February 24 from liver cancer[164] and diabetes.[165] A memorial ceremony was held at Graham Chapel in Washington University.[166] He is buried next to his wife at Ferncliff Cemetery.[167]

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 8.

- ^ "レオ シロタ". Kotobank (in Japanese). Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 41.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 9.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 10.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 42.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 12.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 42–43.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 13.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 43.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 25.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 34.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 35.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 24.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 32.

- ISBN 0-394-46890-2.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 33.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 44.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 41.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b c Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 48.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 43.

- ^ a b Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 46.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Lehmann, Lotte (1938). Midway in My Song: The Autobiography of Lotte Lehmann. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company. p. 148.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 45.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 47.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 50.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 55.

- ^ Evans 2000.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 57.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 61.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 63.

- ^ a b c d Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 40.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 64.

- ^ a b c d Yamamoto 2019, p. 65.

- ^ a b Sirota Gordon 2003.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 67.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 69.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 49.

- ^ a b Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 60.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 55.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 144.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 56.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 146.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 64.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 182.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 135.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 132.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 133.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 134.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 150.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 149.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 83.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 107.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 147.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 118.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 119.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 125.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 127.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 165.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, pp. 156–157.

- ^ a b c Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 81.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 83.

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 167.

- ^ a b Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 82.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 168.

- ^ Newman, Joseph (1942). "11: Toward the New Order". Goodbye Japan (1st ed.). New York City: L. B. Fischer. p. 318.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 170.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 174.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 176.

- ^ Kishi, Kensuke (August 26, 2022). "戦争に翻弄されたレオ・シロタ〜生涯を「亡命者」として生きた". ステラnet (in Japanese). Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 175.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 178.

- ^ a b Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 91.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 179.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 92.

- ^ Sirota, Leo (March 1954). "Mementos, Made in Japan". Theatre Arts. 38 (3): 84–85.

- ^ a b Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 93.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 184.

- ^ a b Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 20.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, pp. 184–185.

- ISBN 978-1-4214-0730-2.

- ^ Hecht 2013, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 86.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 94.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 17.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 185.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, pp. 186–187.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 188.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 189.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 140.

- ^ "Event: Leo Sirota, Piano". Carnegie Hall Data Lab. Archived from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 191.

- New York Times. p. 30.

- ^ Levinger, Henry W. (May 1947). "Leo Sirota's Debut". Musical Courier. 135 (9): 12.

- ^ "Leo Sirota, Pianist, April 15". Musical America. 67 (6): 12, 22. April 25, 1947.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, pp. 192–193.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 193.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 202.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 203.

- ^ Japan Times. November 26, 1963. p. 5.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, pp. 203–204.

- ^ a b c d Yamamoto 2019, p. 204.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 205.

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- Japan Times. p. 4.

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 206.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 208.

- Japan Times. December 7, 1963. p. 4.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 209.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sirota Gordon 1997, p. 150.

- ^ a b Yamamoto 2019, p. 210.

- Japan Times. United Press International. February 27, 1965. p. 2.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Yamamoto 2019, p. 211.

Sources

- Evans, Allan (February 6, 1998). "The Sirota Archives: Rare Russian Masterpieces". Arbiter Records. Archived from the originalon February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- Evans, Allan (June 6, 2000). "Leo Sirota: Tokyo Farewell Recital and Liszt Program". Arbiter Records. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ISBN 4-7700-2145-3.

- Sirota Gordon, Beate (June 6, 2003). "Leo Sirota: A Chopin Recital". Arbiter Records. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- Yamamoto, Takashi (2019). Leo Sirota: The Pianist Who Loved Japan. Translated by Bantock, Gavin; Inukai, Takao. ISBN 978-4-9910037-1-4.