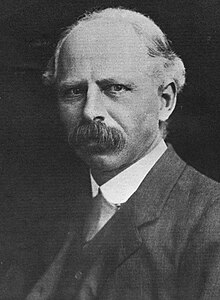

Leonard Hobhouse

Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse,

Life

Hobhouse was born in

Hobhouse was also an

Hobhouse was never religious. He wrote in 1883 that he was "in politics... a firm radical. In religion... an (if possible yet firmer)

Economic policy

Hobhouse was important in underpinning the turn-of-the-century 'New Liberal' movement of the Liberal Party under leaders like H. H. Asquith and David Lloyd George. He distinguished between property held 'for use' and property held 'for power'. Governmental co-operation with trade unions could therefore be justified as helping to counter the structural disadvantage of employees in terms of power. He also theorised that property was acquired not only by individual effort but by societal organisation. Essentially, wealth had a social dimension and was a collective product. That means that those who had property owed some of their success to society and thus had some obligation to others. He believed that to provide theoretical justification for a level of redistribution provided by the new state pensions.

Hobhouse disliked

Civil liberty

His work also presents a positive vision of liberalism in which the purpose of liberty is to enable individuals to develop, not solely that freedom is good in itself. Hobhouse said that coercion should be avoided not for lack of regard for other people's well-being but because coercion is ineffective at improving their lot.

While rejecting the practical doctrines of classical liberalism like laissez-faire, Hobhouse praised the work of earlier classical liberals like Richard Cobden in dismantling an archaic order of society and older forms of coercion. Hobhouse believed that one of the defining characteristics of liberalism was its emancipatory character, something that he believed ran constant from classical liberalism to the social liberalism he advocated. He nevertheless emphasised the various forms of coercion already existing in society apart from government. Therefore, he proposed that to promote liberty, the state must ameliorate other forms of social coercion.

Hobhouse held out hope that Liberals and what would now be called the

Foreign policy

Hobhouse was often disappointed that fellow collectivists in Britain at the time also tended to be imperialists. Hobhouse opposed the

Works

- The Labour Movement (1893) reprinted 1912

- Theory of Knowledge: a contribution to some problems of logic and metaphysics (1896)

- Mind in Evolution (1901)

- Democracy and Reaction (1905)

- Morals in Evolution: a Study in Comparative Ethics in two volumes (1906)

- Liberalism (1911)

- Social Evolution and Political Theory (1911)

- Development and Purpose (1913)

- The Material Culture and Social Institutions of the Simpler Peoples : An Essay in Correlation (London: Chapman and Hall, 1915, reprinted 1930).

- Questions Of War And Peace (1916)

- The Metaphysical Theory of the State: a criticism (1918)

- The Rational Good: a study in the logic of practice (1921)

- The Elements of Social Justice (1922)

- Social Development: its Nature and Conditions (1924)

- Sociology and Philosophy: a Centenary Collection of Essays and Articles (1966), with a preface by Sydney Caine and an introduction by Morris Ginsberg

See also

- Reason and Revolution

- Contributions to liberal theory

References

- ^ doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33906. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ ISBN 0-521-43112-3.

- ^ a b Hobson, J. A.; Ginsberg, Morris (1931). L. T. Hobhouse: His Life and Work. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- ^ ISBN 0-521-22304-0.

External links

Quotations related to Leonard Hobhouse at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Leonard Hobhouse at Wikiquote Works by or about Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse at Wikisource

Works by or about Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse at Wikisource- Works by Leonard Hobhouse in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Leonard Hobhouse at Internet Archive

- Short biography by David Howarth MP

- Profile at the Liberal International

- That Englishwoman (1989) at IMDb – A film directed by Dirk de Villiers