Lesser goldfinch

| Lesser goldfinch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| |

| Female both S. p. hesperophilus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Fringillidae |

| Subfamily: | Carduelinae |

| Genus: | Spinus |

| Species: | S. psaltria

|

| Binomial name | |

| Spinus psaltria (Say, 1822)

| |

| Subspecies | |

|

see text | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Fringilla psaltria ( protonym )Carduelis psaltria Astragalinus psaltria | |

The lesser goldfinch (Spinus psaltria) is a very small

As is the case for all three New World goldfinches (and some of their siskin relatives), lesser goldfinch males have a black forehead, which females lack. Males in this species vary strikingly in back color across their range, from green in western North America to black from Texas south to South America. Five subspecies are often recognized.

Taxonomy

The lesser goldfinch was

Five subspecies are recognised:[6]

- S. p. hesperophilus (Oberholser, 1903) – west USA and northwest Mexico

- S. p. witti Grant, PR, 1964 – Tres Marias Islands(off west Mexico)

- S. p. psaltria (Say, 1822) – west-central USA to south-central Mexico

- S. p. jouyi (Ridgway, 1898) – southeast Mexico and northwest Belize

- S. p. colombianus (Lafresnaye, 1843) – south Mexico to Peru and Venezuela

Description

This petite species is not only the smallest

Males are easily recognized by their bright yellow underparts and big white patches in the tail (outer rectrices) and on the wings (the base of the primaries). They range from having solid black from the back to the upper head including the ear-coverts to having these regions medium green; each of the back, crown and ear regions varies in darkness rather independently though; as a rule, the ears are not darker than the rest. In most of the range, dark birds termed psaltria (the Arkansas black-backed goldfinch) predominate. The light birds are termed hesperophilus (the green-backed goldfinch) and are most common in the far western U.S. and northwestern Mexico.[12]

The zone in which both light and dark males occur on a regular basis is broadest in the north and extends across the width of the

Females' and immatures' upperparts are more or less grayish olive-green; their underparts are yellowish, buffier in immatures. They have only a narrow strip of white on the wings (with other white markings in some forms) and little or no white on the tail. They are best distinguished from other members of the genus by the combination of small size, upperparts without white or yellow, and dark gray bill. In all plumages, this bird can easily be taken for a New World warbler if the typical finch bill is not seen well.

Like other goldfinches, it has an undulating flight in which it frequently gives a call: in this case, a harsh chig chig chig.[14] Another distinctive call is a very high-pitched, drawn-out whistle, often rising from one level pitch to another (teeeyeee) or falling (teeeyooo). The song is a prolonged warble or twitter, more phrased than that of the American goldfinch,[15] often incorporating imitations of other species.

-

Intermediate male;

note mottled back and cap -

male S. p. colombianus, Colombia

-

S. p. hesperophilus at Desert Botanical Garden, Phoenix

Distribution and habitat

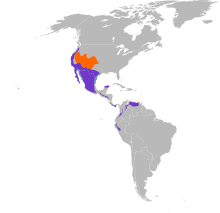

This American goldfinch ranges from the southwestern United States (near the coast, as far north as extreme southwestern Washington) to Venezuela and Peru. It migrates from the colder parts of its U.S. range.

The lesser goldfinch often occurs in flocks or at least loose associations. It utilizes almost any

The nesting season is in summer in the temperate parts of its range; in the tropics it apparently breeds all-year round, perhaps less often in September and October.[17] It lays three or four bluish white eggs in a cup nest made of fine plant materials such as lichens, rootlets, and strips of bark, placed in a bush or at low or middle levels in a tree.

The

Considered a Species of Least Concern by the

References

- . Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- .

- ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Paynter, Raymond A. Jr, ed. (1968). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 14. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. pp. 246–247.

- ^ Koch, Carl Ludwig (1816). System der baierischen Zoologie, Volume 1 (in German). Nürnberg. p. 232.

- ^ Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (2020). "Finches, euphonias". IOC World Bird List Version 10.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Peterson et al. (1990), Sibley (2000)

- ^ Hilty, Steven L., Birds of Venezuela, 2002, Princeton University Press

- ^ ISBN 978-0691048789.

- ^ Birds of the World blog

- ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ a b c d Willoughby (2007)

- ^ Quatro (2007)

- ^ Sibley (2000)

- ^ Peterson et al. (1990)

- ^ Delgado-V. (2006)

- ^ a b Cisneros-Heredia (2006)

Sources

- Cisneros-Heredia, Diego F. (2006): "Notes on breeding, behaviour and distribution of some birds in Ecuador." Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club 126 (2): 153–164. PDF fulltext

- Delgado-V., Carlos A. (2006): "Observación de geofagia por el Jiguero Aliblanco Carduelis psaltria (Fringillidae)." ["Report of geophagy in the Lesser Goldfinch C. psaltria (Fringillidae)".] Boletín de la Sociedad Antioqueña de Ornitología 16 (2): 31–34. [Spanish with English abstract] PDF fulltext

- Howell, Steven N.G. & Webb, Sophie (1995): A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press, Oxford & New York. ISBN 0-19-854012-4

- ISBN 0-395-51424-X

- Quatro, John (2007): Siskins of the World. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ISBN 0-679-45122-6

- Willoughby, Ernest J. (2007): Geographic variation in color, measurements, and molt of the Lesser Goldfinch in North America does not support subspecific designation [English with Spanish abstract]. 2.0.CO;2]

External links

- Lesser goldfinch Species Account - Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Lesser goldfinch - Carduelis psaltria - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- "Lesser goldfinch media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Lesser goldfinch photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Carduelis psaltria at IUCN Red List maps