Lithium (medication)

| |

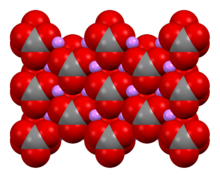

Lithium carbonate, an example of a lithium salt | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Many[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a681039 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

parenteral | |

| Drug class | Mood stabilizer |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Depends on formulation |

| Protein binding | None |

| Metabolism | Kidney |

| Elimination half-life | 24 h, 36 h (elderly)[4] |

| Excretion | >95% kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Certain lithium compounds, also known as lithium salts, are used as psychiatric medication,[4] primarily for bipolar disorder and for major depressive disorder.[4] In lower doses, other salts such as lithium citrate are known as nutritional lithium and have occasionally been used to treat ADHD.[5] Lithium is taken orally (by mouth).[4]

Common side effects include

Lithium salts are classified as mood stabilizers.[4] Lithium's mechanism of action is not known.[4]

In the nineteenth century, lithium was used in people who had

Medical uses

In 1970, lithium was approved by the United States

Bipolar disorder

Lithium is primarily used as a maintenance drug in the treatment of bipolar disorder to stabilize mood and prevent

Schizophrenic disorders

Lithium is recommended for the treatment of schizophrenic disorders only after other antipsychotics have failed; it has limited effectiveness when used alone.[4] The results of different clinical studies of the efficacy of combining lithium with antipsychotic therapy for treating schizophrenic disorders have varied.[4]

Major depressive disorder

If major depressive disorder symptoms fail to respond to standard treatment (such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]), a second agent is sometimes added. A recent systematic review found some evidence of the clinical utility of adjunctive lithium, but the majority of supportive evidence is dated. The same review found no evidence to support the use of lithium for monotherapy.[29]

Monotherapy

There are a few old studies indicating efficacy of lithium for acute depression with lithium having the same efficacy as tricyclic antidepressants.[30] A recent study concluded that lithium works best on chronic and recurrent depression when compared to modern antidepressant (i.e. citalopram) but not for patients with no history of depression.[31]

Prevention of suicide

Lithium is widely believed to prevent suicide, and often used in clinical practice towards that end. However, meta-analyses, faced with evidence-base limitations, have yielded differing results, and it therefore remains unclear whether or not lithium is efficacious in the prevention of suicide.[32][33][34][35][36][37]

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease affects forty-five million people and is the fifth leading cause of death in the 65 plus population.[38][failed verification] There is no complete cure for the disease, currently. However, lithium is being evaluated for its effectiveness as a potential therapeutic measure. One of the leading causes of Alzheimer's is the hyperphosphorylation of the tau protein by the enzyme GSK-3, which leads to the overproduction of amyloid peptides that cause cell death.[38] To combat this toxic amyloid aggregation, lithium upregulates the production of neuroprotectors and neurotrophic factors, as well as inhibiting the GSK-3 enzyme.[39] Lithium also stimulates neurogenesis within the hippocampus, making it thicker.[39] Yet another cause of Alzheimer's disease is the dysregulation of calcium ions within the brain.[40] Too much or too little calcium within the brain can lead to cell death.[40] Lithium is able to restore the intracellular calcium homeostasis through inhibiting the wrongful influx of calcium upstream.[40] It also promotes the redirection of the influx of the calcium ions into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum of the cells to reduce the oxidative stress within the mitochondria.[40]

In 2009, a study was performed by Hampel and colleagues[41] that asked patients with Alzheimer's to take a low dose of lithium daily for three months; it resulted in a significant slowing of cognitive decline, benefitting patients being in the prodromal stage the most.[39] Upon a secondary analysis, the brains of the Alzheimer's patients were studied and shown to have an increase in BDNF markers, meaning they had actually shown cognitive improvement.[39] Another study, a population study this time by Kessing et al.,[42] showed a negative correlation between Alzheimer's disease deaths and the presence of lithium in drinking water.[39] Areas with increased lithium in their drinking water showed less dementia overall in their population.[39]

Monitoring

Those who use lithium should receive regular serum level tests and should monitor thyroid and kidney function for abnormalities, as it interferes with the regulation of

Lithium concentrations in whole blood, plasma, serum or urine may be measured using instrumental techniques as a guide to therapy, to confirm the diagnosis in potential poisoning victims or to assist in the forensic investigation in a case of fatal overdosage. Serum lithium concentrations are usually in the range of 0.5–1.3

Lithium salts have a narrow therapeutic/toxic ratio, so should not be prescribed unless facilities for monitoring plasma concentrations are available. Doses are adjusted to achieve plasma concentrations of 0.4[46][47] to 1.2 mmol Li+

/L [48] on samples taken 12 hours after the preceding dose.

Given the rates of thyroid dysfunction, thyroid parameters should be checked before lithium is instituted and monitored after 3–6 months and then every 6–12 months.[49]

Given the risks of kidney malfunction, serum creatinine and eGFR should be checked before lithium is instituted and monitored after 3–6 months at regular interval. Patients who have a rise in creatinine on three or more occasions, even if their eGFR is > 60 ml/min/ 1.73m2 require further evaluation, including a urinalysis for haematuria, proteinuria, a review of their medical history with attention paid to cardiovascular, urological and medication history, and blood pressure control and management. Overt proteinuria should be further quantified with a urine protein to creatinine ratio.[50]

Discontinuation

For patients who have achieved long term remission, it is recommended to discontinue lithium gradually and in a controlled fashion.[51][30]

Discontinuation symptoms may occur in patients stopping the medication including irritability, restlessness and somatic symptoms like vertigo, dizziness or lightheadedness. Symptoms occur within the first week and are generally mild and self-limiting within weeks. [52]

Cluster headaches, migraine and hypnic headache

Studies testing

Adverse effects

The adverse effects of lithium include:[53][54][55][56][57][58][59]

- Very Common (> 10% incidence) adverse effects

- Confusion

- Constipation (usually transient, but can persist in some)

- Decreased memory

- Diarrhea (usually transient, but can persist in some)

- Dry mouth

- EKG changes — usually benign changes in T waves

- Hand tremor (usually transient, but can persist in some) with an incidence of 27%. If severe, psychiatrist may lower lithium dosage, change lithium salt type or modify lithium preparation from long to short acting (despite lacking evidence for these procedures) or use pharmacological help[60]

- Headache

- Hyperreflexia — overresponsive reflexes

- Leukocytosis — elevated white blood cell count

- Muscle weakness (usually transient, but can persist in some)

- Myoclonus — muscle twitching

- Nausea (usually transient)[49]

- Polydipsia — increased thirst

- Polyuria — increased urination

- Renal (kidney) toxicity which may lead to chronic kidney failure

- Vomiting (usually transient, but can persist in some)

- Vertigo

- Weight gain

- Common (1–10%) adverse effects

- Acne

- Extrapyramidal side effects — movement-related problems such as muscle rigidity, parkinsonism, dystonia, etc.

- Euthyroid goitre — i.e. the formation of a goitre despite normal thyroid functioning

- Hypothyroidism — a deficiency of thyroid hormone.

- Hair loss/hair thinning

- Unknown incidence

- Sexual dysfunction[49]

- Hypoglycemia[61]

- Glycosuria

Lithium carbonate can induce a 1–2 kg of weight gain.[62]

In addition to tremors, lithium treatment appears to be a risk factor for development of parkinsonism-like symptoms, although the causal mechanism remains unknown.[63]

Most side effects of lithium are dose-dependent. The lowest effective dose is used to limit the risk of side effects.

Hypothyroidism

The rate of hypothyroidism is around six times higher in people who take lithium. Low thyroid hormone levels in turn increase the likelihood of developing depression. People taking lithium thus should routinely be assessed for hypothyroidism and treated with synthetic thyroxine if necessary.[62]

Because lithium competes with the

Pregnancy and breast feeding

Lithium is a

While it appears to be safe to use while breastfeeding a number of guidelines list it as a contraindication[73] including the British National Formulary.[74]

Kidney damage

Lithium has been associated with several forms of kidney injury.

Hyperparathyroidism

Lithium-associated

Interactions

Lithium

Lithium is primarily

There are also drugs that can increase the clearance of lithium from the body, which can result in decreased lithium levels in the blood. These drugs include theophylline, caffeine, and acetazolamide. Additionally, increasing dietary sodium intake may also reduce lithium levels by prompting the kidneys to excrete more lithium.[84]

Lithium is known to be a potential precipitant of

High doses of

Classical psychedelics such as psilocybin and LSD may cause seizures if taken while using lithium, although further research is needed.[90]

Overdose

Lithium toxicity, which is also called lithium overdose and lithium poisoning, is the condition of having too much lithium in the blood. This condition also happens in persons that are taking lithium in which the lithium levels are affected by drug interactions in the body.

In acute toxicity, people have primarily gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea, which may result in volume depletion. During acute toxicity, lithium distributes later into the central nervous system resulting in mild neurological symptoms, such as dizziness.[49]

In chronic toxicity, people have primarily neurological symptoms which include nystagmus, tremor, hyperreflexia, ataxia, and change in mental status. During chronic toxicity, the gastrointestinal symptoms seen in acute toxicity are less prominent. The symptoms are often vague and nonspecific.[91]

If the lithium toxicity is mild or moderate, lithium dosage is reduced or stopped entirely. If the toxicity is severe, lithium may need to be removed from the body.

Mechanism of action

The specific biochemical mechanism of lithium action in stabilizing mood is unknown.[4]

Upon ingestion, lithium becomes widely distributed in the central nervous system and interacts with a number of neurotransmitters and receptors, decreasing norepinephrine release and increasing serotonin synthesis.[92]

Unlike many other

Lithium both directly and indirectly inhibits

Another mechanism proposed in 2007 is that lithium may interact with nitric oxide (NO) signalling pathway in the central nervous system, which plays a crucial role in neural plasticity. The NO system could be involved in the antidepressant effect of lithium in the Porsolt forced swimming test in mice.[103][104] It was also reported that NMDA receptor blockage augments antidepressant-like effects of lithium in the mouse forced swimming test,[105] indicating the possible involvement of NMDA receptor/NO signaling in the action of lithium in this animal model of learned helplessness.

Lithium possesses neuroprotective properties by preventing apoptosis and increasing cell longevity.[106]

Although the search for a novel lithium-specific receptor is ongoing, the high concentration of lithium compounds required to elicit a significant pharmacological effect leads mainstream researchers to believe that the existence of such a receptor is unlikely.[107]

Oxidative metabolism

Evidence suggests that

Dopamine and G-protein coupling

During mania, there is an increase in

Glutamate and NMDA receptors

GABA receptors

Cyclic AMP secondary messengers

Lithium's therapeutic effects are thought to be partially attributable to its interactions with several signal transduction mechanisms.

Inositol depletion hypothesis

Lithium treatment has been found to inhibit the enzyme

Neurotrophic Factors

Various neurotrophic factors such as BDNF and mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor have been shown to be modulated by various mood stabilizers.[113]

History

Lithium was first used in the 19th century as a treatment for

By the turn of the 20th century, as theory regarding mood disorders evolved and so-called "brain gout" disappeared as a medical entity, the use of lithium in psychiatry was largely abandoned; however, a number of lithium preparations were still produced for the control of renal calculi and uric acid diathesis.

Also in 1949, the

The rest of the world was slow to adopt this treatment, largely because of deaths which resulted from even relatively minor overdosing, including those reported from use of lithium chloride as a substitute for table salt. Largely through the research and other efforts of Denmark's Mogens Schou and Paul Baastrup in Europe,[114] and Samuel Gershon and Baron Shopsin in the U.S., this resistance was slowly overcome. Following the recommendation of the APA Lithium Task Force (William Bunney, Irvin Cohen (Chair), Jonathan Cole, Ronald R. Fieve, Samuel Gershon, Robert Prien, and Joseph Tupin[118]), the application of lithium in manic illness was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 1970,[119] becoming the 50th nation to do so.[18] In 1974, this application was extended to its use as a preventive agent for manic-depressive illness.

Fieve, who had opened the first lithium clinic in North America in 1966, helped popularize the psychiatric use of lithium through his national TV appearances and his bestselling book, Moodswing. In addition, Fieve and David L. Dunner developed the concept of "rapid cycling" bipolar disorder based on non-response to lithium.

Lithium has now become a part of Western popular culture. Characters in

7 Up

As with

Salts and product names

As of 2017 lithium was marketed under many brand names worldwide, including Cade, Calith, Camcolit, Carbolim, Carbolit, Carbolith, Carbolithium, Carbolitium, Carbonato de Litio, Carboron, Ceglution, Contemnol, D-Gluconsäure, Lithiumsalz, Efadermin (Lithium and Zinc Sulfate), Efalith (Lithium and Zinc Sulfate), Elcab, Eskalit, Eskalith, Frimania, Hypnorex, Kalitium, Karlit, Lalithium, Li-Liquid, Licarb, Licarbium, Lidin, Ligilin, Lilipin, Lilitin, Limas, Limed, Liskonum, Litarex, Lithane, Litheum, Lithicarb, Lithii carbonas, Lithii citras, Lithioderm, Lithiofor, Lithionit, Lithium, Lithium aceticum, Lithium asparagicum, Lithium Carbonate, Lithium Carbonicum, Lithium Citrate, Lithium DL-asparaginat-1-Wasser, Lithium gluconicum, Lithium-D-gluconat, Lithiumcarbonaat, Lithiumcarbonat, Lithiumcitrat, Lithiun, Lithobid, Lithocent, Lithotabs, Lithuril, Litiam, Liticarb, Litijum, Litio, Litiomal, Lito, Litocarb, Litocip, Maniprex, Milithin, Neurolepsin, Plenur, Priadel, Prianil, Prolix, Psicolit, Quilonium, Quilonorm, Quilonum, Téralithe, and Theralite.[1]

Research

Tentative evidence in

See also

References

- ^ a b "Lithium brands". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 – Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 – Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Lithium Salts". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-451-49659-1. Archivedfrom the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- PMID 30506447.

- ^ from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "Lithium Carbonate Medication Guide" (PDF). U.S. FDA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2. Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ PMID 8313612.

- ^ PMID 10885179. Archived from the original(PDF) on 1 April 2012.

- hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Lithium – Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-915274-22-2. Archivedfrom the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ S2CID 256840.

- ^ PMID 19538681.

- PMID 31152444.

- S2CID 248161621.

- PMID 37789577.

- S2CID 257665886.

- ^ Semple, David "Oxford Hand Book of Psychiatry" Oxford Press. 2005.[page needed]

- S2CID 246754349.

- S2CID 26227696.

- PMID 17156154.

- PMID 16961421.

- PMID 36111461.

- from the original on 20 February 2024. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84184-515-9. Archivedfrom the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ISBN 978-3-319-31212-5.

- PMID 36111461.

- S2CID 219942979.

- S2CID 199451710.

- PMID 36384820.

- PMID 23814104.

- PMID 17042835.

- ^ PMID 33667416.

- ^ S2CID 235385875.

- ^ PMID 35363371.

- PMID 19573486.

- PMID 28832877.

- ^ Healy D. 2005. Psychiatric Drugs Explained. 4th ed. Churchhill Livingstone: London.[page needed]

- .

- ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- mmol/L plasma lithium level in adults for prophylaxis of recurrent affective bipolar manic-depressive illness Camcolit 250 mg Lithium Carbonate Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback MachineRevision 2 December 2010, Retrieved 5 May 2011

- PMID 12091193.) concluded the higher rate of relapse for the "low" dose was due to abrupt changes in the lithium serum levels[improper synthesis?]

- S2CID 38042857.

- ^ PMID 27900734.

- PMID 30390660.

- PMID 15207941.

- S2CID 243025798.

- ^ a b c DrugPoint® System (Internet). Truven Health Analytics, Inc. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomsen Healthcare. 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-9805790-8-6.

- ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ^ "lithium (Rx) - Eskalith, Lithobid". Medscape. WebMD. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ "Lithobid (lithium carbonate) tablet, film coated, extended release". National Library of Medicine. Noven Therapeutics, LLC. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2013 – via DailyMed.

- ^ "Product Information Lithicarb (Lithium carbonate)". TGA eBusiness Services. Aspen Pharmacare Australia Pty Ltd. Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- S2CID 9496408.

- S2CID 33784257.

- S2CID 33307427.

- ^ .

- ISBN 978-1-107-06600-7.

- PMID 2516883.

- ^

Keshavan MS, Kennedy JS (2001). Drug-induced dysfunction in psychiatry. ISBN 978-0-89116-961-1.

- ^ "Safer lithium therapy". NHS National Patient Safety Agency. 1 December 2009. Archived from the original on 30 January 2010.

- ^

Bendz H, Schön S, Attman PO, Aurell M (February 2010). "Renal failure occurs in chronic lithium treatment but is uncommon". Kidney International. 77 (3): 219–224. PMID 19940841.

- PMID 11948561.

- PMID 18982835.

- PMID 25565896.

- S2CID 902424.

- S2CID 25166015.

- ^ "Lithium use while Breastfeeding". LactMed. 10 March 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ "Lithium carbonate". Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- PMID 18519084.

- ^ PMID 17943083.

- S2CID 6732380.

- PMID 15806465.

- ^ S2CID 4552345.

- PMID 12846754.

- ^ "Lithium". WebMD. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ PMID 8834421.

- PMID 24991789.

- ISBN 978-1-60913-713-7.

- ^ Boyer EW. "Serotonin syndrome". UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ Wijdicks EF. "Neuroleptic malignant syndrome". UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- PMID 9296146.)

- PMID 9008777.

- PMID 22690368.

- PMID 34348413.

- PMID 22690368.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- PMID 10481837.

- S2CID 6045269.

- ^ OCLC 979600268.

- S2CID 20669215.

- PMID 17100580.

- PMID 18046304.

- S2CID 11421586.

- PMID 7761465.

- S2CID 43250471.

- PMID 22240080.

- S2CID 44805917.

- S2CID 22656735.

- S2CID 41634565.

- ^ S2CID 26907074.

- ISBN 978-0-08-098429-2. Archivedfrom the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- PMID 12890311.

- OCLC 979600268.

- PMID 25687772.

- S2CID 6707456.

- PMID 10208444.

- S2CID 222257563.

- ^ S2CID 25861243.

- ^ "Lithium: Discovered, Forgotten and Rediscovered". inhn.org. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ "Obituary – Shirley Aldythea Andrews – Obituaries Australia". oa.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 26 October 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2006.

- PMID 11252660.

- (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2006.

- ^ Agassi T (12 March 1996). "Sting is now older, wiser and duller". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ^ "7 UP: The Making of a Legend". Cadbury Schweppes: America's Beverages.

- ^ "Urban Legends Reference Pages: 7Up". 6 August 2004. Archived from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- ^ anonymous (13 July 1950). "ISALLY'S (ad)". Painesville Telegraph. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ S2CID 208019043.

- ^ "How and when to take lithium". nhs.uk. 14 August 2023. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- S2CID 23864616.

- S2CID 209448822.

- PMID 22918486.

Further reading

- Mota de Freitas D, Leverson BD, Goossens JL (2016). "Lithium in Medicine: Mechanisms of Action". In Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel R (eds.). Metal ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 16. Springer. pp. 557–584. PMID 26860311.

- Phelps J (19 September 2014). "Lithium Basics". Psych. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- Phillips ML (16 February 2006). "Exposing lithium's circadian action". The Scientist. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

External links

- "Mood Stabilizers: An Updated List and Links". PsychEducation.org. April 2004. Archived from the original on 11 August 2004.