Livyatan

| Livyatan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cast of skull at the Natural History Museum of the University of Pisa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Superfamily: | Physeteroidea |

| Family: | incertae sedis |

| Genus: | †Livyatan Lambert et al., 2010 |

| Species: | †L. melvillei

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Livyatan melvillei Lambert et al., 2010

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Livyatan is an

Livyatan's total length has been estimated to be about 13.5–17.5 m (44–57 ft), almost similar to that of the modern sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), making it one of the largest predators known to have existed. The teeth of Livyatan measured 36.2 cm (1.19 ft), and are the largest biting teeth of any known animal, excluding tusks. It is distinguished from the other raptorial sperm whales by the basin on the skull spanning the length of the snout. The spermaceti organ contained in that basin is thought to have been used in echolocation and communication, or for ramming prey and other sperm whales. The whale may have interacted with the large extinct shark megalodon (Otodus megalodon), competing with it for a similar food source. Its extinction was probably caused by a cooling event at the end of the Miocene period causing a reduction in food populations. The geological formation where the whale has been found has also preserved a large assemblage of marine life, such as sharks and marine mammals.

Taxonomy

Research history

In November 2008, a partially preserved skull, as well as teeth and the lower jaw, belonging to L., the

The discoverers originally assigned—in July 2010—the English name of the biblical monster, Leviathan, to the whale as Leviathan melvillei. However, the scientific name Leviathan was also the

Additional specimens

During the late 2010s and 2020s, fossils of large isolated sperm whale teeth were reported from various Miocene and Pliocene localities mostly along the Southern Hemisphere. These teeth have been identified to be of similar size and shape with that of the L. melvillei holotype and may be species of Livyatan. However, it is commonplace that authors do not identify such teeth as a conclusive species of Livyatan, instead opting to assign an open nomenclature in which the biological classifications of the specimens are restricted to comparisons or affinities with Livyatan. This is mostly because isolated teeth tend to not be informative enough to be identified at the species level, meaning that there is some undeterminable possibility that they belong to an undescribed close relative of Livyatan rather than Livyatan itself.[9][10]

In 2016 in Beaumaris Bay, Australia, a large sperm whale tooth measuring 30 cm (1 ft), specimen NMV P16205, was discovered in Pliocene strata by a local named Murray Orr, and was nicknamed the "Beaumaris sperm whale" or the "giant sperm whale". The tooth was donated to Museums Victoria at Melbourne. Though it has not been given a species designation, the tooth looks similar to those of L. melvillei, indicating it was a close relative. The tooth is dated to around 5 mya,[12][13][14] and so is younger than the L. melvillei holotype by around 4 or 5 million years.[1]

In 2018, palaeontologists led by David Sebastian Piazza, while revising the collections of the Bariloche Paleontological Museum and the Municipal Paleontological Museum of Lamarque, uncovered two incomplete sperm whale teeth cataloged as MML 882 and BAR-2601 that were recovered from the Saladar Member of the Gran Bajo del Gualicho Formation in the Río Negro Province of Argentina, a deposit that dates between around 20–14 mya. The partial teeth measure 142 millimetres (6 in) and 178 millimetres (7 in) in height, respectively. Anatomical analyses of the specimens found that much of their characteristics are identical to L. melvillei except in width, in which the diameter of both teeth are smaller. Because of this, along with only isolated teeth being available, the palaeontologists chose to assign an open nomenclature, identifying both specimens as aff. Livyatan sp.[9][15]

In 2019, palaeontologist Romala Govender reported the discovery of two large sperm whale teeth from Pliocene deposits near the Hondeklip Bay village of Namaqualand in South Africa. The pair of teeth, which are stored in the Iziko South African Museum and cataloged as SAM-PQHB-433 and SAM-PQHB-1519, measure 325.12 millimetres (13 in) and 301.2 millimetres (12 in) in height, respectively, the latter having its crown missing. Both teeth have open pulp cavities, indicating that both whales were young. The teeth are very similar in shape and size to the mandibular teeth of the L. melvillei holotype, and were identified as cf. Livyatan. Like the Beaumaris specimen, the South African teeth are dated to around 5 mya.[10]

In 2023, graduate student Kristin Watmore and paleontologist Donald Prothero reported in a preprint a giant sperm whale tooth identified as cf. Livaytan discovered in Mission Viejo, California during housing development during the 1980s and '90s. The tooth resided in the Orange County Paleontological Collection cataloged as OCPC 3125/66099 and was incomplete but nevertheless measured at least 250 millimetres (10 in) in length and 86 millimetres (3 in) in diameter. Due to poor geographic recording at the time of its discovery, the exact stratigraphic locality was unknown, but it was reported to have come from a zone that contains both the mid-Miocene Monterey Formation and younger Capistrano Formation, the latter dating between 6.6 and 5.8 mya. The authors found the preservation of the tooth to be more consistent with Capistrano Formation fossils. At the area where part of the tooth broke off revealed layers of cementum and dentin of thickness within the known range of L. melvillei teeth. OCPC 3125/66099 represented the first evidence that either Livyatan or Livyatan-like whales were not restricted to the Southern Hemisphere and likely indicated a possibly global distribution of the cetaceans.[11]

Phylogeny

Livyatan was part of a fossil

The cladogram below is modified from Lambert et al. (2017) and represents the phylogenetic relationships between Livyatan and other sperm whales, with genera identified as macroraptorial sperm whales in bold.[1][8][16]

| Physeteroidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

The body length of Livyatan is unknown since only the holotype skull is preserved. Lambert and colleagues estimated the body length of Livyatan using Zygophyseter and modern sperm whales as a guide. The authors opted to use the relationship between the bizygomatic width (distance between the opposite zygomatic processes) of the skull and body length because of the variable rostrum length in modern sperm whales and the rostrum of Livyatan being proportionally shorter. Doing so produced length estimates of 13.5 m (44 ft) when using the modern sperm whale and 16.2–17.5 m (53–57 ft) when using Zygophyseter.[1][18] It has been estimated to weigh 57 tonnes (62.8 short tons) based on the length estimate of 17.5 m (57 ft).[19] By comparison, the modern sperm whale length measures on average 11 m (36 ft) for females and 16 m (52 ft) for males,[20] with some males reaching up to 20.7 m (68 ft) long.[21][22][23] The large size was probably an anti-predator adaptation, and allowed it to feed on larger prey. Livyatan is the largest fossil sperm whale discovered, and was also one of the biggest-known predators, having the largest bite of any tetrapod.[1][8]

Skull

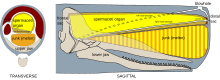

The holotype skull of Livyatan was about 3 m (9.8 ft) long. Like other raptorial sperm whales, Livyatan had a wide gap in between the

Teeth

Unlike the modern sperm whale, Livyatan had functional teeth in both jaws. The wearing on the teeth indicates that the teeth sheared past each other while biting down, meaning it could bite off large portions of flesh from its prey. Also, the teeth were deeply embedded into the gums and could interlock, which were adaptations to holding struggling prey. None of the teeth of the holotype were complete, and none of the back teeth were well-preserved. The lower jaw contained 22 teeth, and the upper jaw contained 18 teeth. Unlike other sperm whales with functional teeth in the upper jaw, none of the tooth roots were entirely present in the premaxilla portion of the snout, being at least partially in the maxilla. Consequently, its tooth count was lower than those sperm whales, and, aside from the modern dwarf (Kogia sima) and pygmy (K. breviceps) sperm whales, it had the lowest tooth count in the lower jaw of any sperm whale.[1][8]

The most robust teeth in Livyatan were the fourth, fifth and sixth teeth in each side of the jaw. The well-preserved teeth all had a height greater than 31 cm (1 ft), and the largest teeth of the holotype were the second and third on the left lower jaw, which were calculated to be around 36.2 cm (1.2 ft) high. The first right tooth was the smallest at around 31.5 cm (1 ft).[1][8] The Beaumaris sperm whale tooth measured around 30 cm (1 ft) in length, and is the largest fossil tooth discovered in Australia.[13][14] These teeth are thought to be among the largest of any known animal, excluding tusks.[1][8] Some of the lower teeth have been shown to contain a facet for when the jaws close, which may have been used to properly fit the largest teeth inside the jaw. In the front teeth, the tooth diameter decreased towards the base. This was the opposite for the back teeth, and the biggest diameters for these teeth were around 11.1 cm (4.4 in) in the lower jaw. All teeth featured a rapid shortening of the diameter towards the tip of the tooth, which were probably in part due to wearing throughout their lifetimes. The curvature of the teeth decreased from front to back, and the lower teeth were more curved at the tips than the upper teeth. The front teeth projected forward at a 45° angle, and, as in other sperm whales, cementum was probably added onto the teeth throughout the animal's lifetime.[1][8]

All tooth sockets were cylindrical and single-rooted. The tooth sockets increased in size from the first to the fourth and then decreased, the fourth being the largest at around 197 mm (7.8 in) in diameter in the upper jaws, which is the largest of any known whale species. The tooth sockets were smaller in the lower jaw than they were in the upper jaw, and they were circular in shape, except for the front sockets which were more ovular.[1][8]

Basin

The fossil skull of Livyatan had a curved basin, known as the supracranial basin, which was deep and wide. Unlike other raptorial sperm whales, but much like in the modern sperm whale, the basin spanned the entire length of the snout, causing the entire skull to be concave on the top rather than creating a snout as seen in Zygophyseter and Acrophyseter. The supracranial basin was the deepest and widest over the braincase, and, unlike other raptorial sperm whales, it did not overhang the eye socket. It was defined by high walls on the sides. The antorbital notches, which are usually slit-like notches on the sides of the skull right before the snout, were inside the basin. A slanting crest on the temporal fossa directed towards the back of the skull separated the snout from the rest of the skull, and was defined by a groove starting at the antorbital processes on the cheekbones. The basin had two foramina in the front, as opposed to the modern sperm whale which has one foramen on the maxilla, and to the modern dwarf and pygmy sperm whales which have several in the basin. The suture in the basin between the maxilla and the forehead had an interlocking pattern.[8]

Palaeobiology

Hunting

Livyatan was an

Spermaceti organ

The supracranial basin in its head suggests that Livyatan had a large spermaceti organ, a series of oil and wax reservoirs separated by connective tissue. The uses for the spermaceti organ in Livyatan are unknown. Much like in the modern sperm whale, it could have been used in the process of biosonar to generate sound for locating prey. It is possible that it was also used as a means of acoustic displays, such as for communication purposes between individuals. It may have been used for acoustic stunning, which would have caused the bodily functions of a target animal to shut down from exposure to the intense sounds.[1][3][8]

Another theory says that the enlarged forehead caused by the presence of the spermaceti organ is used in all sperm whales between males fighting for females during mating season by head-butting each other, including Livyatan and the modern sperm whale. It may have also been used to ram into prey; if this is the case, in support of this, there have been two reports of modern sperm whales attacking whaling vessels by ramming into them, and the organ is disproportionally larger in male modern sperm whales.[1][3][8]

An alternate theory is that sperm whales, including Livyatan, can alter the temperature of the wax in the organ to aid in buoyancy. Lowering the temperature increases the density to have it act as a weight for deep-sea diving, and raising the temperature decreases the density to have it pull the whale to the surface.[1][3][8]

Palaeoecology

Fossils conclusively identified as L. melvillei have been found in Peru and Chile. However, additional isolated large sperm whale teeth from other locations including California, Australia, Argentina and South Africa have been identified as a species or possible close relative of Livyatan.

The holotype of L. melvillei is from the

L. melvillei is also known from the

The Beaumaris sperm whale was found in the

The South African teeth attributed as cf. Livyatan are from the

Extinction

Livyatan-like sperm whales became extinct by the early Pliocene likely due to a cooling trend causing baleen whales to increase in size and decrease in diversity, becoming coextinct with the smaller whales they fed on.[1][3][4][5] Their extinction also coincides with the emergence of the orcas as well as large predatory globicephaline dolphins, possibly acting as an additional stressor to their already collapsing niche.[9]

Notes

- ^ Zanclean range is based on Livyatan-like fossils assigned open nomenclature as cf. Livyatan. Upper range for confirmed L. melvillei is 8.9 mya

References

- ^ S2CID 4369352. Archived from the original(PDF) on 1 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Livyatan melvillei". Fossilworks. Gateway to the Paleobiology Database. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d Ghosh, Pallab (30 June 2010). "'Sea monster' whale fossil unearthed". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ a b Sample, Ian (30 June 2010). "Fossil sperm whale with huge teeth found in Peruvian desert". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 September 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Created by showman Albert Koch for the Missourium hoax.

- .

- ^ from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 202019648.

- ^ .

- ^ a b Jeffrey, Andy (2016). "Giant killer sperm whales once cruised Australia's waters (and we have a massive tooth to prove it)". Earth Touch News Network. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Huge Tooth Reveals Prehistoric Moby Dick in Melbourne". Australasian Science Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-76056-338-7. Archived(PDF) from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4214-2326-5. Archivedfrom the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Toscano, A.; Abad, M.; Ruiz, F.; Muñiz, F.; Álvarez, G.; García, E.; Caro, J. A. (2013). "Nuevos Restos de Scaldicetus (Cetacea, Odontoceti, Physeteridae) del Mioceno Superior, Sector Occidental de la Cuenca del Guadalquivir (Sur de España)" [New Remains of Scaldicetus (Cetacea, Odontoceti, Physeteridae) from the Upper Miocene, Western Sector of the Guadalquivir Basin]. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas (in Spanish). 30 (2). Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- .

- S2CID 129682627.

- ISBN 978-0-691-12757-6.

- ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- OCLC 60244977.

- PMID 25649000.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "New Leviathan Whale Was Prehistoric "Jaws"?". National Geographic. 30 June 2010. Archived from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ Loch, C.; Gutstein, C. S.; Pyenson, N. D.; Clementz, M. T. (2019). But did it eat other whales? New enamel microstructure and isotopic data on Livyatan, a large physteroid from the Atacama region, northern Chile. 79th Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Abstract of Papers.

- (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ Gutstein, Carolina; Horwitz, Fanny; Valenzuela-Toro, Ana M.; Figueroa-Bravo, Constanza P. (2015). "Cetáceos fósiles de Chile: Contexto evolutivo y paleobiogeográfico" (PDF). Publicación Ocasional del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Chile (in Spanish). 63: 339–383. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Suárez, Mario (2015). "Tiburones, rayas y quimeras (Chondrichthyes) fósiles de Chile" (PDF). Publicación Ocasional del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Chile (in Spanish). 63: 17–33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Sallaberry, Michel; Soto-Acuna, Sergio; Yury-Yanez, Roberto; Alarcon, Jhonatan; Rubilar-Rogers, David (2015). "Aves fósiles de Chile" (PDF). Publicación Ocasional del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Chile (in Spanish). 63: 265–291. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Valenzuela Toro, Ana M.; Gutstein, Carolina (2015). "Mamíferos marinos (excepto cetáceos) fósiles de Chile" (PDF). Publicación Ocasional del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Chile (in Spanish). 63: 385–400. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Soto-Acuña, Sergio; Otero, Rodrigo A.; Rubilar-Rogers, David; Vargas, Alexander O. (2015). "Arcosaurios no avianos de Chile" (PDF). Publicación Ocasional del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Chile (in Spanish). 63: 209–263. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- .

- ^ "Beaumaris Bay Fossil Site, Beach Rd, Beaumaris, VIC, Australia". Australian Heritage Database. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ Smith, B. (2012). "Trove of ancient secrets submerged under the sea". The Age. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ Long, J. (2015). "We need to protect the fossil heritage on our doorstep". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ "Beaumaris (Miocene of Australia)". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Pether, John (1994). The sedimentology, palaeontology, and stratigraphy of coastal-plain deposits at Hondeklip Bay, Namaqualand, South Africa (MSc). University of Cape Town.

- S2CID 90979340.

External links

- 'Sea monster' fossil found in Peru desert by CNN

- Ancient sperm whale's giant head uncovered from Los Angeles Times (The skull is on display in National History Museum in Lima)

- A killer sperm whale with details on sperm whale evolution

- Videos

- The Worlds Largest BITE on YouTube

- The jaws of the Leviathan on YouTube

- Leviathan melvillei on YouTube(a collection of images of discovery)