Lobopodia

| Lobopodia Temporal range: Descendant taxa

Euarthropoda survive to Recent, possible Ediacaran ichnofossils[2] | |

|---|---|

| |

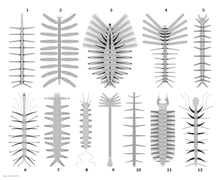

| Reconstruction of various lobopodians. 1: Microdictyon sinicum, 2: Diania cactiformis, 3: Collinsovermis monstruosus, 4: Luolishania longicruris, 5: Onychodictyon ferox, 6: Hallucigenia sparsa, 7: Aysheaia pedunculata, 8: Antennacanthopodia gracilis, 9: Facivermis yunnanicus, 10: Paucipodia inermis, 11: Jianshanopodia decora, 12: Hallucigenia fortis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| Superphylum: | Ecdysozoa |

| (unranked): | Panarthropoda |

| Phylum: | †"Lobopodia" Snodgrass 1938 |

| Groups included | |

| |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

|

Crown-group Euarthropoda

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Lobopodians are members of the informal group Lobopodia

The oldest near-complete

Definitions

The Lobopodian concept varies from author to author. This corresponds to "A" in the image to the left.

An alternative, broader definition of Lobopodia would also incorporate Onychophora and Tardigrada,

Lobopodia has, historically, sometimes included

Representative taxa

The better-known

Morphology

-

Maximum size of the 3 species of Hallucigenia (from top, H. fortis, H. hongmeia and H. sparsa) in scale.

-

Fossils of Xenusion, a lobopodian that might have grown up to 20 centimeters.

Most lobopodians were only a few centimeters in length, while some genera grew up to over 20 centimeters.[7] Their bodies are annulated, although the presence of annulation may differ between position or taxa, and sometimes difficult to discern due to their close spacing and low relief on the fossil materials.[37] Body and appendages are circular in cross-section.[37]

Head

Due to the usually poor preservation, detailed reconstructions of the head region are only available for a handful of lobopodian species.[38][22] The head of a lobopodian is more or less bulbous,[5] and sometime possesses a pair of pre-ocular, presumely protocerebral[23] appendages – for example, primary antennae[39][36][23][40] or well-developed frontal appendages,[41][19][42][7][5] which are individualized from the trunk lobopods[23][43] (with the exception of Antennacanthopodia, which have two pairs of head appendages instead of one[39]). Mouthparts may consist of rows of teeth[37][22][42][7][44] or a conical proboscis.[38][5][45] The eyes may be represented by a single ocellus or by numerous[46] pairs of simple ocelli,[5] as has been shown in Luolishania[36] (=Miraluolishania[46][47]), Ovatiovermis,[45] Onychodictyon,[38] Hallucigenia,[22] Facivermis,[47] and less certainly Aysheaia as well.[38] However, in gilled lobopodians like Kerygmachela, the eyes are relatively complex reflective patches[48] that may had been compound in nature.[49]

Trunk and lobopods

The trunk is elongated and composed of numerous body segments (

The lobopods are flexible and loosely conical in shape, tapering from the body to tips that may [21][5] or may not [39][51][10] bear claws. The claws, if present, are hardened structures with a shape resembling a hook or gently-curved spine.[37][52][36][21][5] Claw-bearing lobopods usually have two claws, but single claws are known (e.g. posterior lobopods of luolishaniids[36][45][40]), as are more than two (e.g. three in Tritonychus,[53] seven in Aysheaia[41]) depending on its segmental or taxonomical association.[21] In some genera, the lobopods bear additional structures such as spines (e.g. Diania[51]), fleshy outgrowths (e.g. Onychodictyon[38]), or tubercules (e.g. Jianshanopodia[7]). There is no sign of arthropodization (development of a hardened exoskeleton and segmental division on panarthropod appendages) in known members of lobopodians, even for those belonging to the arthropod stem-group (e.g. gilled lobopodians and siberiids), and the suspected case of arthropodization on the limbs of Diania[54] is considered to be a misinterpretation.[51][10]

Differentiation (tagmosis) between trunk somites barely occurs, except in hallucigenids and luolishaniids, where numerous pairs of their anterior lobopods are significantly slender (hallucigenids) or setose (luolishaniids) in contrast to their posterior counterparts.[5][22][45][24][40]

Internal structures

The gut of lobopodians is often straight, undifferentiated,[55] and sometimes preserved in the fossil record in three dimensions. In some specimens the gut is found to be filled with sediment.[37] The gut consists of a central tube occupying the full length of the lobopodian's trunk,[7] which does not change much in width - at least not systematically. However, in some groups, specifically the gilled lobopodians and siberiids, the gut is surrounded by pairs of serially repeated, kidney-shaped gut diverticulae (digestive glands).[7][42][55] In some specimens, parts of the lobopodian gut can be preserved in three dimensions. This cannot result from phosphatisation, which is usually responsible for 3-D gut preservation,[56] because the phosphate content of the guts is under 1%; the contents comprise quartz and muscovite.[37] The gut of the representative Paucipodia is variable in width, being widest at the centre of the body. Its position in the body cavity is only loosely fixed, so flexibility is possible.

Not much is known about the neural anatomy of lobopodians due to the spare and mostly ambiguous fossil evidence. Possible traces of a nervous system were found in

In some extant

Categories

Based on external morphology, lobopdians may fall under different categories — for example the general worm-like taxa as "

Armoured lobopodians

Armoured lobopodians referred to

Gilled lobopodians

Siberion and similar taxa

Siberion, Megadictyon and Jianshanopodia may be grouped as siberiids (order Siberiida),[27] jianshanopodians[21] or "giant lobopodians"[63] by some literatures. They are generally large — body length ranging between 7[27] and 22 centimeters[42] (2¼ to 8⅔ inches) — xenusiid lobopodians with widen trunk, stout trunk lobopods without evidence of claws, and most notably a pair of robust frontal appendages.[8] With the possible exception of Siberion,[27][21] they also have digestive glands like those of a gilled lobopodian and basal euarthropod.[7][42][8][55] Their anatomy represent transitional forms between typical xenusiids and gilled lobopodians,[27] eventually placing them under the basalmost position of arthropod stem-group.[7][42][8][23]

Paleoecology

Lobopodians possibly occupied a wide range of

Not much is known about the

Distribution

During the Cambrian, lobopodians displayed a substantial degree of biodiversity. One species is known from each of the Ordovician and Silurian periods,[12][64] with a few more known from the Carboniferous (Mazon Creek) — this represents the paucity of exceptional lagerstatten in post-Cambrian deposits.

Phylogeny

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Neutralized phylogeny between lobopodians and other Extant panarthropod taxa are in bold. Relationship between the total-group of extant panarthropod phyla is unresolved. |

The overall phylogenetic interpretation on lobopodians has changed dramatically since their discovery and first description.

Based on their apparently

Stem-group arthropods

Compared to other panarthropod stem-groups, suggestion on the lobopodian members of arthropod stem-group is relatively consistent — siberiid like Megadictyon and Jianshanopodia occupied the basalmost position, gilled lobopodians Pambdelurion and Kerygmachela branch next, and finally lead to a clade compose of Opabinia, Radiodonta and Euarthropoda (crown-group arthropods).[21][8][22][60][23][45][24] Their positions within arthropod stem-group are indicated by numerous arthropod groundplans and intermediate forms (e.g. arthropod-like digestive glands, radiodont-like frontal appendages and dorso-ventral appendicular structures link to arthropod biramous appendages).[8][23] Lobopodian ancestry of arthropods also reinforced by genomic studies on extant taxa — gene expression support the homology between arthropod appendages and onychophoran lobopods, suggests that modern less-segmented arthropodized appendages evolved from annulated lobopodous limbs.[43] On the other hand, primary antennae and frontal appendages of lobopodians and dinocaridids may be homologous to the labrum/hypostome complex of euarthropods, an idea support by their protocerebral origin[8][23][49] and developmental pattern of the labrum of extant arthropods.[43][23]

-

Radiodonts are stem-group arthropods with gilled lobopodian-like body flaps, arthropodized frontal appendages and stalked compound eyes.

-

Restoration of Pambdelurion a "gilled lobopodian" related to arthropods, which has both pairs of lobopods and lateral flaps.

Diania, a genus of armoured lobopodian with stout and spiny legs, were originally thought to be associated within the arthropod stem-group based on its apparently arthropod-like (arthropodized) trunk appendages.[54] However, this interpretation is questionable as the data provided by the original description are not consistent with the suspected phylogenic relationships.[69][70] Further re-examination even revealed that the suspected arthropodization on the legs of Diania was a misinterpretation — although the spine may have hardened, the remaining cuticle of Diania's legs were soft (not harden nor scleritzed), lacking any evidence of pivot joint and arthrodial membrane, suggest the legs are lobopods with only widely spaced annulations.[51][10] Thus, the re-examination eventually reject the evidence of arthropodization (sclerotization, segmentation and articulation) on the appendages as well as the fundamental relationship between Diania and arthropods.[51][10]

Stem-group onychophorans

While

Stem-group tardigrades

Lobopodian taxa of the tardigrade stem-group is unclear.[5] Aysheaia[45][24][40] or Onychodictyon ferox[21][22] had been suggest to be a possible member, based on the high claw number (in Aysheaia) and/or terminal lobopods with anterior-facing claws (in both taxa).[21] Although not widely accepted, there are even suggestions that Tardigrada itself representing the basalmost panarthropod or branch between the arthropod stem-group.[68]

Stem-group panarthropods

It is unclear that which lobopodians represent members of the panarthropod stem-group, which were branched just before the last common ancestor of extant panarthropod phyla. Aysheaia may have occupied this position based on its apparently basic morphology;[58][21][22][47] while other studies rather suggest luolishaniid and hallucigenid,[45][24][40] two lobopodian taxa which had been resolved as members of stem-group onychophorans as well.[5][21][22][53][47]

Described genera

As of 2018, over 20 lobopodian genera have been described.[10] The fossil materials being described as lobopodians Mureropodia apae and Aysheaia prolata are considered to be disarticulated frontal appendages of the radiodonts Caryosyntrips and Stanleycaris, respectively.[72][73][74] Miraluolishania was suggested to be synonym of Luolishania by some studies.[36][75][47] The enigmatic Facivermis was later revealed to be a highly specialized genus of luolishaniid lobopodians.[27][45][47]

- Antennacanthopodia[39]

- Aysheaia[41]

- Carbotubulus[13]

- Cardiodictyon[76]

- Collinsium[77]

- Collinsovermis[40]

- Diania[54][51]

- Facivermis[47]

- Fusuconcharium[78]

- Hadranax[79]

- Hallucigenia[17][18][52][22]

- Jianshanopodia[7]

- Kerygmachela[20][19][49]

- Lenisambulatrix[10]

- Luolishania[18] (=Miraluolishania)[36][47]

- Megadictyon[80][42]

- Microdictyon[50]

- Mobulavermis[81]

- Omnidens?[82]

- Onychodictyon[76][38]

- Orstenotubulus[83]

- Ovatiovermis[45]

- Pambdelurion[26][57][44]

- Paucipodia[84][37]

- Quadratapora[78]

- Siberion[27]

- Thanahita[24]

- Tritonychus[53]

- Utahnax[85]

- Xenusion[16]

References

- PMID 22885062.

- ISSN 0016-7649.

- ^ Snodgrass, R.E. (1938). "Evolution of the Annelida, Onychophora, and Arthropoda". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 97 (6): 1–159.

- ^ PMID 9809012.

- ^ PMID 26439350.

- ^ a b c Budd, Graham; Peel, John (1998-12-01). "A new Xenusiid lobopod from the early Cambrian Sirius Passet fauna of North Greenland". Palaeontology. 41: 1201–1213.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Jianni Liu; Degan Shu; Jian Han; Zhifei Zhang & Xingliang Zhang (2006). "A large xenusiid lobopod with complex appendages from the Lower Cambrian Chengjiang Lagerstätte" (PDF). Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 51 (2): 215–222. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ S2CID 7751936.

- ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ PMID 30237414.

- S2CID 4313285.

- ^ S2CID 11561169.

- ^ PMID 22885062.

- ^ PMID 23902914.

- ^ .

- ^ ISSN 1502-3931.

- ^ S2CID 4309565.

- ^ ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ S2CID 85645934.

- ^ S2CID 4341971.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

- ^ S2CID 205244325.

- ^ PMID 27989966.

- ^ PMID 30224988.

- PMID 27725256.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-412-75420-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dzik, Jerzy (1 July 2011). "The xenusian-to-anomalocaridid transition within the lobopodians" (PDF). Bollettino della Societa Paleontologica Italiana. 50: 65–74. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022.

- ^ Pentastomida - Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa

- ^ Treatise on Zoology - Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. The Crustacea, Volum 5

- ISSN 0020-7519.

- PMID 15129965.

- S2CID 4427443.

- PMID 31270537.

- S2CID 239958264

- Bibcode:1989wlbs.book.....G.[page needed]

- ^ PMID 19293001.

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 23232391.

- ^ S2CID 53056128.

- ^ S2CID 225593728.

- ^ .

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 28957524.

- ^ S2CID 88758267.

- ^ PMID 28137244.

- ^ ISSN 1502-3931.

- ^ PMID 32109391.

- PMID 30518575.

- ^ PMID 29523785.

- ^ a b c d e f Chen, J.Y., Zhou, G.Q., Ramsköld, L. (1995a). The Cambrian lobopodian Microdictyon sinicum. Bulletin of the National Museum of Natural Science 5, 1–93 (Taichung, Taiwan).

- ^ S2CID 220463025.

- ^ ISSN 1802-8225.

- ^ PMID 27677816.

- ^ S2CID 4324509.

- ^ PMID 24785191.

- S2CID 85606166.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

- ^ S2CID 37935884.

- .

- ^ S2CID 205242881.

- .

- S2CID 1913482.

- S2CID 225478171.

- S2CID 129609503.

- ISSN 1936-6434.

- JSTOR 1304837.

- .

- ^ ISSN 0044-5231.

- S2CID 4417903.

- S2CID 4310063.

- ISSN 0044-5231.

- S2CID 135026011.

- ^ "Aysheaia prolata from the Utah Wheeler Formation (Drumian, Cambrian) is a frontal appendage of the radiodontan Stanleycaris - Acta Palaeontologica Polonica". www.app.pan.pl. Retrieved 2020-01-08.

- ^ "Reply to Comment on "Aysheaia prolata from the Utah Wheeler Formation (Drumian, Cambrian) is a frontal appendage of the radiodontan Stanleycaris" with the formal description of Stanleycaris - Acta Palaeontologica Polonica". www.app.pan.pl. Retrieved 2020-01-08.

- S2CID 128619311.

- ^ S2CID 85077111.

- PMID 26124122.

- ^ S2CID 85293118.

- ^ BUDD, G. E., PEEL, J. S. (1998). A new xenusiid lobopod from the Early Cambrian Sirius Passet fauna of North Greenland. Palaeontology, 41, 6, 1201–1213.

- ^ Luo, H. L., Hu, S. X. & Chen, L. Z. Early Cambrian Chengjiang Fauna from Kunming Region, China. 129 (Yunnan Science and Technology Press, 1999).

- . Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- S2CID 83582128.

- S2CID 83993887.

- S2CID 131555757.

- S2CID 250076505.