Louisiana in the American Civil War

| Louisiana | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Admitted to the Confederacy March 21, 1861 (3rd) | | |

| Population |

| |

| Forces supplied |

- Union troops: 29,000 (24,000 black; 5,000 white)[2][3] total | |

| Governor | Thomas Moore Henry Allen | |

| Lieutenant Governor | ||

Senators | ||

| Representatives | List | |

| Restored to the Union | July 9, 1868 | |

| History of Louisiana |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Confederate States in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

|

| Dual governments |

| Territory |

|

Allied tribes in Indian Territory |

Louisiana declared that it had

Politics and strategy in Louisiana

Secession

On January 8, 1861, Louisiana Governor

The strategies advanced to defend Louisiana and the other

In March 1861, George Williamson, the Louisianan state commissioner, addressed the Texan secession convention, where he called upon the slave states of the U.S. to declare secession from the Union in order to continue practicing slavery:

With the social balance wheel of slavery to regulate its machinery, we may fondly indulge the hope that our Southern government will be perpetual ... Louisiana looks to the formation of a Southern confederacy to preserve the blessings of African slavery ...

— George Williamson, speech to the Texan secession convention (March 1861).[7]

One Louisianan artillery soldier gave his reasons for fighting for the Confederacy, stating that "I never want to see the day when a negro is put on an equality with a white person. There is too many free niggers ... now to suit me, let alone having four millions."[8]

Union plans

The Union's response to Moore's leveraged secession was embodied in U.S. President Abraham Lincoln's realization that the Mississippi River was the "backbone of the Rebellion." If control of the river were accomplished, the largest city in the Confederacy would be taken back for the Union, and the Confederacy would be split in half. Lincoln moved rapidly to back Admiral David Dixon Porter's idea of a naval advance up the river to both capture New Orleans and maintain Lincoln's political support; by supplying cotton to northern textile manufacturers and renewing trade and exports from the port of New Orleans. The U.S. Navy would become both a formidable invasion force and a means of transporting Union forces, along the Mississippi River and its tributaries. This strategic vision would prove victorious in Louisiana.[10][11]: 10–78

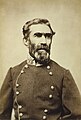

Notable Civil War leaders from Louisiana

A number of notable leaders were associated with Louisiana during the

Governor Thomas Overton Moore, came held office from 1860 through early 1864. When war erupted, he unsuccessfully lobbied the Confederate government in Richmond for a strong defense of New Orleans. Two days before the city surrendered in April 1862, Moore and the legislature abandoned Baton Rouge as the state capital, relocating to Opelousas in May. Thomas Moore organized military resistance at the state level, ordered the burning of cotton, cessation of trade with the Union forces, and heavily recruited troops for the state militia.[15]

-

Gen.P.G.T. Beauregard

-

Gen.

Braxton Bragg -

Lt. Gen.

Richard Taylor -

Brig. Gen. and Gov.

Henry W. Allen -

Brig. Gen.

Albert G. Blanchard -

Brig. Gen.

Randall L. Gibson -

Brig. Gen.

Henry Gray -

Brig. Gen.

Harry T. Hays -

Brig. Gen.

St. John Liddell -

Brig. Gen.

Alfred Mouton -

Brig. Gen.

Francis T. Nicholls -

Brig. Gen.

Leroy A. Stafford

Battles in Louisiana

Battles in Louisiana tended to be concentrated along the major waterways, like the

Restoration to Union

Following the end of the Civil War, Louisiana was part of the Fifth Military District.

After meeting the requirements of

As part of the Compromise of 1877, under which Southern Democrats acknowledged Republican Rutherford B. Hayes as president, there was the understanding that the Republicans would meet certain demands. One affecting Louisiana was the removal of all U.S. military forces from the former Confederate states.[16] At the time, U.S. troops remained in only Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida, but the Compromise saw their complete withdrawal from the region.

See also

- List of Louisiana Confederate Civil War units, a list of Confederate Civil War units from Louisiana.

- List of Louisiana Union Civil War units, a list of Union Civil War units from Louisiana.

- History of slavery in Louisiana

Notes

- Abbreviations used in these notes

- Official atlas: Atlas to accompany the official records of the Union and Confederate armies.

- ORA (Official records, armies): War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies.

- ORN (Official records, navies): Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion.

References

- ^ Sacher, John M. Confederate Soldiers | 64 Parishes. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ Hunter, G. Howard. Unionist Troops in Louisiana | 64 Parishes. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ Sacher, John M. Civil War Louisiana. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ISBN 0-8071-1945-8.

- ISBN 978-0-521-22979-1.

- ^ Hearn, pp. 2-31.

- ^ Winkler, E.W. (1861). Journal of the Secession Convention of Texas. Texas. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ISBN 0-19-509-023-3. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ Official atlas: plate XC.

- ^ Chester G. Hearn, The Capture of New Orleans, 1862 (LSU Press, 1995)

- ISBN 0-87338-486-5.

- ^ Hearn, pp. 22-31.

- ISBN 0-8317-3264-4.

- ^ Hearn, p. 129.

- ^ Hearn, pp. 2-3.

- ^ Woodward, C. Vann (1966). Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 169–171.

Further reading

- Ayres, Thomas. Dark and Bloody Ground: The Battle of Mansfield and the Forgotten Civil War in Louisiana (2001)

- Campbell, Anne (2007). Louisiana: The History of an American State. Clairmont Press. ISBN 978-1567331356.

- Dew, Charles B. "Who Won the Secession Election in Louisiana?." Journal of Southern History (1970): 18–32. in JSTOR

- Dew, Charles B. "The Long Lost Returns: The Candidates and Their Totals in Louisiana's Secession Election." Louisiana History (1969): 353–369. in JSTOR

- Dimitry, John. Confederate Military History of Louisiana: Louisiana in the Civil War, 1861–1865 (2007)

- Dufrene, Dennis J. Civil War Baton Rouge, Port Hudson and Bayou Sara: Capturing the Mississippi. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2012. ISBN 9781609493516.

- Hearn, Chester G. (1995). The Capture of New Orleans 1862. ISBN 0-8071-1945-8.

- Hollandsworth Jr, James G. The Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience During the Civil War (LSU Press, 1995)

- Johnson, Ludwell H. Red River Campaign, Politics & Cotton in the Civil War Kent State University Press (1993). ISBN 0-87338-486-5.

- Lathrop, Barnes F. "The Lafourche District in 1861–1862: A Problem in Local Defense." Louisiana History (1960) 1#2 pp: 99–129. in JSTOR

- McCrary, Peyton. Abraham Lincoln and Reconstruction: The Louisiana Experiment (1979)

- Peña, Christopher G. Touched by War: Battles Fought in the Lafourche District. Thibodaux, Louisiana: C.G.P. Press, 1998.

- Peña, Christopher G. Scarred By War: Civil War in Southeast Louisiana (2004)

- Pierson, Michael D. Mutiny at Fort Jackson: The Untold Story of the Fall of New Orleans (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2008)

- Ripley, C. Peter. Slaves and Freedmen in Civil War Louisiana (1976)

- Sledge, Christopher L. "The Union's Naval War in Louisiana, 1861–1863" (Army Command and General Staff College, 2006) online

- ISBN 0-8071-0834-0.

- Wooster, Ralph. "The Louisiana Secession Convention." Louisiana Historical Quarterly (1951) 34#1 pp: 103–133.