Lower respiratory tract infection

| Lower respiratory tract infection | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conducting passages | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

| Frequency | 291 million (2015)[1] |

| Deaths | 2.74 million (2015)[2] |

Lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) is a term often used as a synonym for

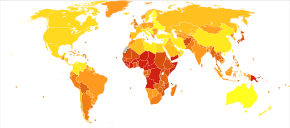

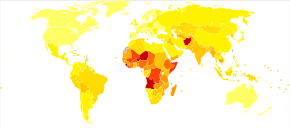

In 2015 there were about 291 million cases.[1] These resulted in 2.74 million deaths down from 3.4 million deaths in 1990.[5][2] This was 4.8% of all deaths in 2013.[5]

Bronchitis

Bronchitis describes the swelling or inflammation of the[6] bronchial tubes. Additionally, bronchitis is described as either acute or chronic depending on its presentation and is also further described by the causative agent. Acute bronchitis can be defined as acute bacterial or viral infection of the larger airways in healthy patients with no history of recurrent disease.[7] It affects over 40 adults per 1000 each year and consists of transient inflammation of the major bronchi and trachea.[8] Most often it is caused by viral infection and hence antibiotic therapy is not indicated in immunocompetent individuals.[9][6] Viral bronchitis can sometimes be treated using antiviral medications depending on the virus causing the infection, and medications such as anti-inflammatory drugs and expectorants can help mitigate the symptoms.[10][6] Treatment of acute bronchitis with antibiotics is common but controversial as their use has only moderate benefit weighted against potential side effects (nausea and vomiting), increased resistance, and cost of treatment in a self-limiting condition.[8][11] Beta2 agonists are sometimes used to relieve the cough associated with acute bronchitis. In a recent systematic review it was found there was no evidence to support their use.[6]

Acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis (AECB) are frequently due to non-infective causes along with viral ones. 50% of patients are colonised with Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, or Moraxella catarrhalis.

Pneumonia

Pneumonia occurs in a variety of situations and treatment must vary according to the situation.[10] It is classified as either community or hospital acquired depending on where the patient contracted the infection. It is life-threatening in the elderly or those who are immunocompromised.[12][13] The most common treatment is antibiotics and these vary in their adverse effects and their effectiveness.[12][14] Pneumonia is also the leading cause of death in children less than five years of age in low income countries.[14] The most common cause of pneumonia is pneumococcal bacteria, Streptococcus pneumoniae accounts for 2/3 of bacteremic pneumonias.[15] Invasive pneumococcal pneumonia has a mortality rate of around 20%.[13] For optimal management of a pneumonia patient, the following must be assessed: pneumonia severity (including treatment location, e.g., home, hospital or intensive care), identification of causative organism, analgesia of chest pain, the need for supplemental oxygen, physiotherapy, hydration, bronchodilators and possible complications of emphysema or lung abscess.[16]

Causes

Typical bacterial Infections:

Atypical bacterial Infections:

- Legionella pneumophila

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- Chlamydophila pneumoniae

- Chlamydia psittaci

- Adenovirus

- Influenza A virus

- Influenza B virus

- Human parainfluenza viruses

- Human respiratory syncytial virus

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus(SARS-CoV)

- Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus(MERS-CoV)

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2(SARS-CoV-2)

Prevention

Vaccination helps prevent bronchopneumonia, mostly against

Treatment

Antibiotics do not help the many lower respiratory infections which are caused by parasites or viruses. While acute bronchitis often does not require antibiotic therapy, antibiotics can be given to patients with acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis.

Oxygen supplementation is often recommended for people with severe lower respiratory tract infections.[25] Oxygen can be provided in a non-invasive manner using nasal prongs, face masks, a head box or hood, a nasal catheter, or a nasopharyngeal catheter.[25] For children younger than 15 years old, nasopharyngel catheters or nasal prongs are recommended over a face mask or head box.[25] A Cochrane review in 2014 presented a summary to identify children complaining of severe LRTI, however; further research is required to determine the effectiveness of supplemental oxygen and the best delivery method.[25]

Epidemiology

Lower respiratory infectious disease is the fifth-leading cause of death and the combined leading infectious cause of death, being responsible for 2.74 million deaths worldwide.[26] This is generally similar to estimates in the 2010 Global Burden of Disease study.[27] This total only accounts for Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae infections and does not account for atypical or nosocomial causes of lower respiratory disease, therefore underestimating total disease burden.[citation needed]

Society and culture

Lower respiratory tract infections place a considerable strain on the health budget and are generally more serious than upper respiratory infections.[citation needed]

Workplace burdens arise from the acquisition of a lower respiratory tract infection, with factors such as total per person expenditures and total medical service utilisation demonstrated as greater among individuals experiencing a lower respiratory tract infection.[28]

Pan-national data collection indicates that childhood nutrition plays a significant role in determining the acquisition of a lower respiratory tract infection, with the promotion of the implementation of nutrition program, and policy guidelines in affected countries.[26]

References

- ^ PMID 27733282.)

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 27733281.)

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-0-9925272-1-1.

- PMID 24369343.

- ^ PMID 25530442.)

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ PMID 26333656.

- ^ a b c Antibiotic Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: Antibiotic. 13th ed. North Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines; 2006.

- ^ PMID 26186368.

- ^ Therapeutic guidelines : respiratory. 2nd ed: North Melbourne : Therapeutic Guidelines Limited, 2000.[page needed]

- ^ a b Integrated pharmacology / Clive Page ... [et al.]. 2nd ed: Edinburgh : Mosby, 2002.[page needed]

- PMID 28626858.

- ^ PMID 25300166.

- ^ PMID 23440780.

- ^ PMID 23733365.

- ^ The Merck manual of diagnosis and therapy. 17th ed / Mark H. Beers and Robert Berkow ed: Whitehouse Station, N.J. : Merck Research Laboratories, 1999.[page needed]

- .

- ^ "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002" (xls). World Health Organization. 2002.

- PMID 21951385.

- PMID 18254093.

- ^ PMID 11751764.

- PMID 16319346.

- PMID 29025194.

- PMID 25749735.

- PMID 26408070.

- ^ PMID 25493690.

- ^ PMID 28843578.)

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - S2CID 1541253.

- PMID 29162852.