Lugdunum

Colonia Copia Claudia Augusta Lugdunum | |

Scale model of the city | |

| Location | Lyon, France |

|---|---|

| Region | Gallia Lugdunensis |

| Coordinates | 45°45′35″N 4°49′10″E / 45.75972°N 4.81944°E |

| Type | Roman city |

| Area | 200 hectares |

| History | |

| Builder | Lucius Munatius Plancus |

| Founded | 43 BC |

| Periods | Roman Republic to Roman Empire |

Lugdunum (also spelled Lugudunum, Latin:

The original Roman city was situated west of the confluence of the

heights. By the late centuries of the empire much of the population was located in the Saône River valley at the foot of Fourvière.Name

The Roman city was founded as Colonia Copia Felix Munatia, a name invoking prosperity and the blessing of the gods. The city became increasingly referred to as Lugdunum (and occasionally Lugudunum[7]) by the end of the 1st century AD. During the Middle Ages, Lugdunum was transformed to Lyon by natural sound change.

Lugdunum is a latinization of the

The Celtic god

(also spelled Llew).According to Pseudo-Plutarch, Lugdunum takes its name from an otherwise unattested Gaulish word lugos, that he says means "raven" (κόρακα), and the Gaulish word for an eminence or high ground (τόπον ἐξέχοντα), dunon.[8]

An early interpretation of Gaulish Lugduno as meaning "Desired Mountain" is recorded in a gloss in the 9th-century

Another early medieval folk-etymology of the name, found in gloss on the Latin poet Juvenal, connects the element Lugu- to the Latin word for "light", lux (luci- in compounds) and translates the name as "Shining Hill" (lucidus mons).[11]

Pre-Roman settlements and the area before the founding of the city

Archeological evidence[12] shows Lugdunum was a pre-Gallic settlement as far back as the neolithic era, and a Gallic settlement with continuous occupation from the 4th century BC, during the La Tène period. It was situated on the Fourvière heights above the Saône river. There was trade with Campania for ceramics and wine, and use of some Italic-style home furnishings before the Roman conquest.

The Romans controlled the

Founding of the Roman city

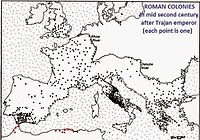

Roman colonization of Lugdunum began during the

Lugdunum seems to have had a population of several thousand at the time of the Roman foundation. The citizens were administratively assigned to the Galerian tribe. The aqueduct of the Monts d'Or, completed around 20 BC, was the first of at least four aqueducts supplying water to the city.

Within 50 years Lugdunum increased greatly in size and importance, becoming the administrative centre of Roman

The proximity to the frontier with Germany made Lugdunum strategically important for the next four centuries, as a staging ground for further Roman expansion into Germany, as well as the de facto capital city and administrative centre of the Gallic provinces. Its large and cosmopolitan population made it the commercial and financial heart of the northwestern provinces as well.

Lugdunum became an imperial

Attention from the Emperors

In its 1st century, Lugdunum was many times the object of attention or visits by the emperors or the imperial family, with its matrimonial regime of power using killing family members.

also contributed to the city's importance and growth.In 12 BC, Drusus completed an administrative census of the area and dedicated an altar to his stepfather Augustus at the junction of the two rivers. Perhaps to promote a policy of conciliation and integration, all the notable men of the three parts of Gaul were invited.

Southeastern Gaul became increasingly Romanized. By 19 AD at least one temple, and the first amphitheatre in Gaul (now known as the Amphitheatre of the Three Gauls) had been built down the slopes of the Croix-Rousse hill, next to the Vaise district where Gallic workers worked with precious metals, copper and also glass or pottery on both sides of the Saône lived (the space between Rhone and Saône was a swamp often flooded) .[16]

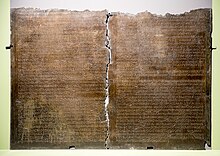

In 48 AD, emperor Claudius asked the Senate to grant the notable men of the three Gauls the right to accede to the Senate. His request was granted and an engraved bronze plaque of the speech (the Claudian Tables) was erected in Lugdunum. Today, the pieces of the huge plaque are the pride of the

Caligula spent time in Lugdunum in 39–40 AD, at the beginning of his third

Claudius was born in Lugdunum in 10 BC and lived there for at least two years. As emperor, he returned in 43 AD en route to his conquest of Britain and stopped again after its victorious conclusion in 47. A fountain honoring his victory has been uncovered. He continued to take a supportive interest in the town, making its noblemen eligible to serve in the Roman Senate, as described above.

During Claudius' reign, the city's strategic importance was enhanced by the bridging of the Rhône river. Its depth and swampy valley had been an obstacle to travel and communication to the east. The new route, termed the compendium, shortened the route south to Vienne and made the roads from Lugdunum to Italy and Germany more direct. By the end of his reign, the city's official name had become Colonia Copia Claudia Augusta Lugudunenisium, abbreviated CCC AVG LVG.

The Lyonnais admiration of Nero was not universally shared; tyranny, extravagance, and negligence fostered resentment, and

In another turnabout for Lugdunum, Galba's policies were immediately unpopular, and in January 69 AD, the Rhine legions quickly threw their support to Vitellius as emperor. They arrived at friendly Lugdunum, where they were persuaded by the Lyonnais to punish nearby Vienne. Vienne quickly laid down weapons and paid a "ransom" to forestall plundering. Meanwhile, Vitellius arrived in Lugdunum, where, according to Tacitus, he formally declared himself Imperator, punished unreliable soldiers, and celebrated with feasts, and with games in the amphitheater. Fortunately for Lugdunum, the would-be emperor and his army hurried into Italy, defeated Otho, and was in turn defeated by Vespasian and the army of the East, bringing the chaos of the Year of the Four Emperors to an end. Under Vespasian, the city briefly resumed production of bronze coinage, ending a shortage in the money supply that had developed in the previous years.[19]

Despite a lack of imperial visits for most of the next century, Lugdunum prospered, until Septimius Severus and the Battle of Lugdunum (see below) brought devastation in 197 AD.

Growth and prosperity in the first centuries of the Empire

In the 2nd century, Lugdunum prospered and grew to a population of 40,000 to 200,000 persons.[20] Four aqueducts brought water to the city's fountains, public baths, and wealthy homes. The aqueducts were well engineered and included several siphons.

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (June 2016) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

It continued to be a provincial capital with additional government functions and services such as the mint and customs service. Lugdunum had at least two

The city itself was run by a "senate" of

The Rhône and Saône rivers were navigable, as were most of the rivers of Gaul, and river traffic was heavy. The Lyonnais company of boatmen (nautae) was the largest and "most honored" in Gaul. Archeological evidence suggests the right bank of the Saône had the largest concentration of wharves, quays and warehouses. Lyonnais boatmen dominated the wine trade from Narbonensis and Italy, as well as oil from Spain, to the rest of Gaul.

The heavy concentration of trade made Lugdunum one of the most cosmopolitan cities of Gaul, and inscriptions attest to a large foreign-born population, especially Italians, Greeks, and immigrants from the oriental provinces of

There is evidence of numerous temples and shrines in Lugdunum. Traditional Gallic gods like mallet-bearing

was built in nearby Vienne, and she also seems to have found special favor in Lugdunum in the late 1st century and 2nd century.Christianity and the first martyrs

The cosmopolitan hospitality to eastern religions may have allowed the first attested Christian community in Gaul to be established in Lugdunum in the 2nd century, led by a bishop Pothinus—who probably was Greek. In 177 it also became the first in Gaul to suffer persecution and martyrdom.

The event was described in a letter from the Christians in Lugdunum to counterparts in Asia, later retrieved and preserved by

Nevertheless, the Christian community either survived or was reconstituted, and under Bishop Irenaeus it continued to grow in size and influence.

Battle of Lugdunum

The 2nd century ended with another struggle for imperial succession. The emperor Pertinax was murdered in 193, and four generals again "contended for the purple". Two of the rivals, Clodius Albinus and Septimius Severus, initially formed a political alliance. Albinus was a former legate of Britannia and commanded legions in Britain and Gaul. Septimius Severus commanded the Pannonian legions, and led them successfully against Didius Julianus near Rome in 193, and defeated Pescennius Niger in 194. Severus consolidated his power in Rome and broke his alliance with Albinus. The Senate supported Severus and declared Albinus a public enemy.

Clodius Albinus had settled with his army near Lugdunum early in 195. There, he had himself proclaimed

Severus brought his army from Italy and Germany toward the end of 196. The armies fought an initial, inconclusive engagement at Tinurtium (Tournus), about 60 km (35 miles) up the Saône from Lugdunum. Albinus retreated with his forces toward Lugdunum.

On 19 February 197, Severus again attacked Clodius Albinus to the northwest of the city. Albinus' army was defeated in the bloody and decisive

Decline of Lugdunum and the Empire

Historical and archeological evidence indicates that Lugdunum never fully recovered from the devastation of this battle.[citation needed]

When mints began to be set up outside Rome after 260 AD, there was a Gallic mint which may have been located at Lugdunum, but more likely at Trier,[23] which was definitely the mint of the Gallic Empire. Aurelian transferred minting from Trier to Lugdunum in 274 AD; it was the sole mint for the western empire.[24]

A major reorganization of imperial administration begun at the end of the 3rd century during the reign of

Lugdunum was no longer the chief city and administrative capital of Gaul. Although the city continued, there seems to have been a population shift from the Fourviere heights where the original Roman city was situated to the river valley below. Other evidence suggests other cities surpassed Lugdunum as trading centers.[citation needed]

Though the

As the Western Empire disintegrated in the 5th century, Lugdunum became the principal city of the Kingdom of the Burgundians in 443 AD. The Lugdunum mint remained in operation under the new rulers.[25]

See also

References

- ^ Gaffiot, Félix (1934). Dictionnaire illustré Latin-Français (in French). Paris: Librairie Hachette. p. 926.

- ISBN 9789463720519.

- ^ Travel Lyon, France: Illustrated Guide, Phrasebook & Maps, p. 9, at Google Books.

- ^ The Roman Remains of Northern and Eastern France: A Guidebook, p. 388, at Google Books.

- ^ Roman Cities, p. 176, at Google Books.

- ^ Roman Cities, p. 335, at Google Books.

- ^ a b Cassius Dio, Roman History, 46.50.4.

- ^ Delattre, Charles (ed.), Pseudo-Plutarque. De fluviorum et montium nominibus et de iis quae in illis inveniuntur, Presses Univ. Septentrion, 2011, pp. 109–111 (in Latin).

- ^ Lugduno desiderato monte: dunum enim montem Lugduno: "desired mountain"; because dunum is mountain" in Endlicher Glossary.

- ^ Toorians, Lauran, "Endlicher's Glossary, an attempt to write its history", in: García Alonso (Juan Luis) (ed.), Celtic and other languages in ancient Europe (2008), pp. 153–184.

- ^ "Lugdunum est civitas Gallie quasi lucidum dunam, id est lucidus mons, dunam enim in Greco mons." in Andreas Hofeneder, Die Religion der Kelten in den antiken literarischen Zeugnissen: Sammlung, Übersetzung und Kommentierung, Volume 2, Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2008, pp. 571–572 (in German).

- ISBN 2-88474-106-2.

- ISBN 9780191647581.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-44192-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-530574-6.

- ^ Pelletier, Jean; Delfante, Charles (2004). Atlas historique du Grand-Lyon. Editions Xavier Lejeune-Libris. p. 34-42.

- ISBN 978-0-19-531589-9. Retrieved 23 Oct 2022.

- ^ Epistulae ad Lucilium, 91.

- ISBN 978-0-19-530574-6.

- ^ L'Express. No. 3074 (in French).

- ^ Whitehead n.d.

- ISBN 978-0-19-530574-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-530574-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-530574-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-530574-6.

Sources

- Cassius Dio. Roman History. XLVI, 50.

- André Pelletier. Histoire de Lyon: de la capitale les Gaules à la métropole européene. Editions Lyonnaises d'Art et d'Histoire. Lyon: 2004. ISBN 2-84147-150-0

- Seneca. Apocolocyntosis. VII.

- Whitehead, Kenneth D. (n.d.). "Witnesses of the Passion". Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

External links

![]() Media related to Lugdunum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lugdunum at Wikimedia Commons