Lumbini pillar inscription

| Lumbini pillar inscription | |

|---|---|

Excavation of the pillar, and discovery of the inscription at the bottom of the pillar. | |

| Material | Polished sandstone |

| Size | Height: Width: |

| Period/culture | 3rd century BCE |

| Discovered | 27°28′11″N 83°16′32″E / 27.469650°N 83.275595°E |

| Place | Lumbini, Nepal. |

| Present location | Lumbini, Nepal. |

The Lumbini pillar inscription, also called the Paderia inscription, is an inscription in the ancient

Discovery of the pillar

Ancient historical records of the Buddhist monuments of the region, made by the ancient Chinese monk-pilgrim

The pillar was supported underground by a brick base, which according to

The existence of the stone pillar itself was already known before the discovery: it had already been reported to Vincent A. Smith by a local landowner named Duncan Ricketts, around twelve years before (circa 1884). Rubbings of the Medieval inscriptions on top of the pillar had been sent by Ricketts, but they were thought of no great consequence.

Discovery of the inscription (1896)

In December 1896,

According to some accounts, Führer found the Lumbini pillar on December 1, and then asked the help of local commander, General

The Brahmi inscription on the pillar gives evidence that Ashoka, emperor of the Maurya Empire, visited the place in 3rd-century BCE and identified it as the birth-place of the Buddha. The inscription was translated by Paranavitana:[10][note 1]

| Translation (English) |

Transliteration (original Brahmi script) |

Inscription (Prakrit in the Brahmi script) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Aftermath

Following the discovery of the pillar, Führer relied on the accounts of ancient Chinese pilgrims to search for

Soon after, Alois Anton Führer was exposed as "a forger and dealer in fake antiquities", and had to resign from his position in 1898.[5] Führer's early archaeological successes had apparently encouraged him to inflate his later discoveries to the point of creating forgeries.[20] Vincent Arthur Smith further revealed in 1901 the blunt truth about Führer's Nepalese discoveries, saying of Führer's description of the archaeological remains at Nigali Sagar that "every word of it is false", and characterizing several of Führer's epigraphic discoveries in the area, including the inscriptions at the alleged Shakya stupas at Sagarwa, as "impudent forgeries".[3][21] However Smith never challenged the authenticity of the Lumbini pillar inscription and the Nigali Sagar inscription.[22]

Führer had written in 1897 a monograph on his discoveries in Nigali Sagar and Lumbini, Monograph on Buddha Sakyamuni's birth-place in the Nepalese tarai[23] which was withdrawn from circulation.[24]

Forged Brahmi inscriptions by Führer

In 1912, the German Indologist

Issues of authenticity

Although generally accepted as genuine, this inscription does raise a few issues in terms of authenticity:

- The Lumbini inscription is in the third person, written by someone reporting a past visit of Devanampriya Priyadarsi, and is not written in Devanampriya Priyadarsi's own name contrary to all other known Edicts of Ashoka.[29][5] So, by its own internal evidence, it may have been written at any time in history after the ruler's visit.[30] In effect, ancient Brahmi was still understood until the beginning of 4th century CE before being rediscovered in the 19th century.[31]

- The qualifier used for the Buddha in the inscription is Sakyamuni (Sakas), although the fully Sanskritized form would be Śakyamuni (𑀰𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀺, pronounced "Shakyamuni").[29][32] The problem is that the rest of the inscription is entirely in Prakrit, and Sanskrit inscriptions are not otherwise attested before the 1st century BCE-1st century CE.[29] "Sakyamuni" only appears in the Lumbini inscription, the other known forms being "Sakiya" in the Piprahwa inscription, "Sakka" in the Pali literature, "Sakka" and "Śakka" in Prakrit literature, "Saka" (Bharhut) and "Śaka" in the epigraphic record.[33]

- The Buddha is never mentioned in the Major Pillar Edicts nor in the Major Rock Edicts, and only appears once in the Bairat Temple inscription.[30]

- The inscription was discovered by Nepalese General Kadga Shameshar, the famous Anton Führer initially was not there and arrived shortly after the discovery. The engraving is in extremely good condition and seems fresh, arguably because the portion of the pillar which contains the inscription remained underground for so long. Still, when Rhys Davids made a copy of the inscription in 1900, he noted that it was "almost as if freshly cut".[34][35] Following re-examination fifty years later, academics commented: "The pillar bears an inscription of Asoka, very well preserved. The lines are straight and letters very tastefully written. It appears as if the inscription has been very recently incised."[36]

These issues were popularized in 2008 by British writer Charles Allen in The Buddha and Dr. Führer: an archaeological scandal.[37][5]

Lumbini was made a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997.[38][39]

Gallery

-

The pillar of Ashoka.

-

The Ashoka inscription on the pillar today.

-

Rubbing of the inscription.

-

The wordsShakyas") in Brahmi script.

-

Luṃmini Gāme (𑀮𑀼𑀁𑀫𑀺𑀦𑀺𑀕𑀸𑀫𑁂, "City of Lumbini") inscription in the Rummindei Edict of Ashoka.

-

Lumbini pillar Medieval inscription of kingRipumalla, 13-14th century CE.

-

Drawing of the pillar capital originally discovered next to the Lumbini pillar.[3]

-

View of the ruins and the Lumbini pillar from the South

-

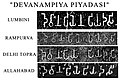

Various "Devanampiya Piyadasi" inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka.

References

- ^ JSTOR 25207888.

- ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1.

- ^ a b c d Mukherji, P. C.; Smith, Vincent Arthur (1901). A report on a tour of exploration of the antiquities in the Tarai, Nepal the region of Kapilavastu;. Calcutta, Office of the superintendent of government printing, India. p. 6.

- ^ JSTOR 25207888.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1.

- ^ Mukherji, P. C.; Smith, Vincent Arthur (1901). A report on a tour of exploration of the antiquities in the Tarai, Nepal the region of Kapilavastu;. Calcutta, Office of the superintendent of government printing, India. p. Plate XIII.

- ^ a b Falk, Harry (January 1998). The discovery of Lumbinī. p. 13.

- ^ Barth, A. (1897). "Decouvertes recentes du Dr. Führer au Nepale". Le Journal des Savants. Académie des inscriptions et belles–lettres: 72.

- ISBN 978-92-3-001208-3.

- ^ Paranavitana, S. (Apr. - Jun., 1962). Rupandehi Pillar Inscription of Asoka, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 82 (2), 163-167

- ^ Weise, Kai; et al. (2013), The Sacred Garden of Lumbini – Perceptions of Buddha's Birthplace (PDF), Paris: UNESCO, pp. 47–48, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-30

- ^ Hultzsch, E. /1925). Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 164-165

- ^ Tsukamoto, Keisho (2006). Reconsidering the Rummindei Pillar Edict of Asoka: In Connection with 'a piece of natural rock' from Mayadevi Temple[permanent dead link], Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies 54 (3), 1113-1120

- ^ Hultzsch, E. (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 164-165

- ^ Hultzsch, E. (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). p. 164.

- ^ Asoka pillar at Rummindei [Lumbini] in the Nepal Tarai, west view of ruins. British Library Online

- ^ "Dr. Fuhrer went from Nigliva to Rummindei where another Priyadasin lat has been discovered... and an inscription about 3 feet below surface, had been opened by the Nepalese" in Calcutta, Maha Bodhi Society (1921). The Maha-Bodhi. p. 226.

- ISBN 978-955-24-0197-8.

- ^ "Fuhrer's attempt to associate the names of eighteen Sakyas, including Mahanaman, with the structures, on the false claim of writings in pre-Asokan characters, was fortunately foiled in time by V.A. Smith, who paid a surprise visit when the excavation was in progress. The forgery was exposed to the public." in Srivastava, K.M. (1979). "Kapilavastu and Its Precise Location". East and West. 29 (1/4): 65–66..

- S2CID 162507322.

- S2CID 147046097.

- ^ Smith, vincent A. (1914). The Early History Of India Ed. 3rd. p. 169.

- ^ Führer, Alois Anton (1897). Monograph on Buddha Sakyamuni's birth-place in the Nepalese tarai. Allahabad : Govt. Press, N.W.P. and Oudh.

- ISBN 978-0-486-41132-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-14-341574-9.

- S2CID 163426828.

- S2CID 163426828.

- ^ S2CID 162507322.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1.

- ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1.

- .

- JSTOR 25210223.

- ^ Rhys Davids, Thomas William (1915). Encyclopaedia Of Religion And Ethics Vol.8. p. 196.

- ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1.

- ^ Dutt, Nalinaksha; Bajpai, Krishna D. (1956). Development of Buddhism in Uttar Pradesh. Publication Bureau, Government of Uttar Pradesh. p. 330.

- ISBN 9781905791934.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Centre - World Heritage Committee Inscribes 46 New Sites on World Heritage List

- ^ "Lumbini, the Birthplace of the Lord Buddha". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

![Drawing of the pillar capital originally discovered next to the Lumbini pillar.[3]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0a/Lumbini_pillar_capital.jpg/107px-Lumbini_pillar_capital.jpg)