Lund Cathedral

| Lund Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Lunds domkyrka | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 85 m (279 ft)[3] |

| Width | 30 m (98 ft)[3] |

| Height | 55 m (180 ft) (to the top of the towers)[4] |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Lund |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Johan Tyrberg |

Lund Cathedral (

Lund Cathedral has been called "the most powerful representative of

The medieval cathedral contains several historic furnishings and works of art. Its main altarpiece was donated to the cathedral in 1398, and it also contains

Historical background

Christian missionaries from present-day Germany and England were active in the

The cathedral was not the first church to be built in Lund; the earliest churches (now vanished) were built in the city at the end of the 10th century.[10] Some kind of rudimentary settlement probably existed at the site of Lund Cathedral at the end of the 10th and early 11th centuries, but no remains of buildings have been found there.[11] Lund Cathedral is one of the oldest stone buildings still in use in Sweden.[12] During the Middle Ages, the cathedral was surrounded by several buildings serving the diocese, of which only Liberiet, which at one point served as a library, survives.[13]

History

Foundation and construction

The earliest written mention of a church in Lund dedicated to

Apart from the obscurity which thus surrounds the very beginning of the history of the cathedral, the construction of Lund Cathedral is probably among the most well documented among any

Unusually for that time, the architect of the cathedral is known by his name, Donatus.[3][22][24] The name appears in both the Necrologium Lundense (as "Donatus architectus") and the Liber daticus vetustior. Donatus may have been responsible for the layout of the crypt and the cathedral above ground as far west as the current north and south portals of the cathedral, although it is difficult to draw any definitive conclusions about his precise role.[22][25] The same is true for his successor, possibly a builder named Ragnar.[26] The building erected during the time of Donatus and his successor show clear influences from Romanesque architecture in Lombardy, conveyed via the Rhine Valley.[27] Donatus himself appears to have been from, or at least educated in, Lombardy.[28] Speyer Cathedral in western Germany is stylistically closely related to Lund Cathedral (especially the crypt), and it has been proposed that Donatus came to Lund from Speyer, where construction more or less ceased in 1106 following the death of Emperor Henry IV.[29][30] Similarities have also frequently been pointed out between Lund Cathedral and Mainz Cathedral, and the design of the apse is similar to that of the Basilica of Saint Servatius in Maastricht.[31] On a more general level, the origins of the style of Lund Cathedral can be found in Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio (Milan), Modena Cathedral and several churches in Pavia, all in northern Italy.[32] Similar stylistic influences can be seen in other cathedrals in Denmark from the same time, for example in Ribe Cathedral.[25]

The building of Lund Cathedral must have involved a large number of people and was a collective undertaking.[31] Comparable but somewhat later workshops at Cologne Cathedral and Uppsala Cathedral employed a workforce of about 100 and 60 people, respectively.[31] The project was instrumental in establishing a workshop where local craftsmen could be educated, and thus disseminating artistic influences from continental Europe to Scandinavia. The stone sculptors Carl stenmästare, Mårten stenmästare and Majestatis were probably all Scandinavians who were educated at the construction site.[32] Many early Romanesque stone churches in the countryside, particularly in Scania but also in the rest of present-day Denmark and Sweden, show direct influences from Lund Cathedral, notably Vä Church (Scania).[33][34] Other examples are e.g. Valby Church (Zealand), Lannaskede Old Church (Småland), Hogstad Church (Östergötland) and Havdhem Church (Gotland).[35][36]

Fire and repairs

The plan and layout of the building consecrated in 1145 was similar to the one seen today. A noticeable difference was that the entire choir was separated from the nave by a wall and reserved for the clergy. The towers were also not built until a few decades later.[37][38] The intention was probably to provide the cathedral with vaults, but instead a flat wooden ceiling was installed.[39] The cathedral was adorned with wall paintings and almost certainly by stained glass windows, but none of these remain.[27] In 1234, the cathedral was heavily damaged by a large fire.[40] Large donations were made to the church in the following years, to allow for repairs.[41] Even so, the need for repairs was continuous for the entire 13th century.[42] Following the fire, the burnt-out ceiling was replaced by brick vaults.[37] Changes were also made to the layout of the westernmost part of the building.[43] A conflict erupted between King Christopher I of Denmark and Archbishop Jakob Erlandsen in 1257 partially because the choir had been enlarged and the seats of the royal family moved, itself a testimony of the growing power of the Church.[44] Two chapels were added to the cathedral during the 14th and 15th centuries; one located adjacent to the two westernmost bays of the south aisle of the nave, and the other as a western extension of the south transept.[45] Buttresses were also added piecemeal to the building during the 13th and 14th centuries, to stabilise the building which was under strain from the new, heavier vaults, the added chapels and the constant ringing of the 8.5 tonne church bell.[46]

Changes by Adam van Düren and later

The German sculptor and builder

Following the Reformation in the 16th century, the diocese lost much of its revenues.

Changes by Carl Georg Brunius and Helgo Zettervall

When the congregation wanted to build a new

The proposal by Zettervall was criticised, not least by Meldahl. Zettervall re-worked the proposal and put forward a revised, less far-reaching proposal in 1864, notably without the central dome.[68] This proposal was also rejected and the plan for a complete overhaul abandoned; however it was at the same time decided that Zettervall would continue working on repairing the cathedral and every year make what changes that were deemed necessary. In this way, Zettervall could piecemeal over the next decades to rebuild the cathedral largely in line with his design from 1864.[60][69]

Between 1832 and 1893, the cathedral was radically transformed by the work of Brunius and Zettervall. All windows were replaced, several vaults and pillars were repaired or rebuilt, and both architects effected extensive changes to the transept. Just as he had suggested, Zettervall had all the buttresses removed and demolished the entire western part of the church, including the towers, and rebuilt them according to his own Neo-Romanesque designs.[70][71]

In the 20th century, archaeological excavations were carried out in and around the cathedral. The building also underwent a major restoration in 1954–1963, led by architect

Architecture and decoration

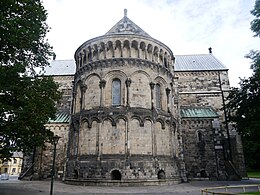

Lund Cathedral has been called "the most powerful representative of Romanesque architecture in the Nordic countries".[3] It lies at some distance from any other buildings and dominates its surroundings.[74] It consists of the two towers built by Zettervall, which flank the main entrance to the west. Behind them a nave with two aisles open up to a transept that is somewhat higher than the nave. A short flight of stairs thus connect the nave with the choir as well as with the crypt under the choir. The choir ends in an apse. Inside, the bays of the cathedral are supported by groin vaults. The number of bays in the aisles are the double of that in the nave. The arches that separate the nave from the aisles are supported by piers and pillars of alternating width. The crypt has over forty shallow groin vaults supported by pillars with cushion capitals. It is sparsely lit by low small windows and remains largely unchanged since 1123.[31][75][76]

Seen from outside, the different elements of the building are clearly discernible as independent volumes, "as if they could be taken apart and put together again".

- Overview of Lund Cathedral

-

Plan c. 1200.

-

Aerial view from the south east

-

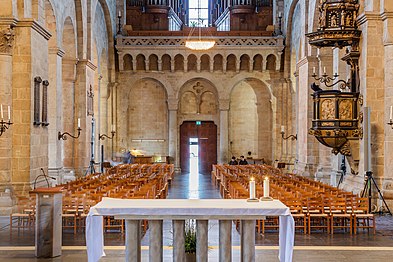

View from the entrance towards east

-

View from the altar towards west

Sculptures

When it comes to stone sculpture, Lund Cathedral was the most lavishly decorated Romanesque building to be built in the Nordic countries, according to art historian

The fluted columns also found in the crypt are similar in style to English Norman architecture and may indicate that the very first artistic influences came from the area bordering the English Channel.[87] Apart from these columns however, the rich stone ornamentation is clearly Lombardic in style, meaning related to north Italian art of the period.[27] Among these is a baldachin now immured in the east wall of the north transept which may have been part of the original western facade; Its columns have Corinthian capitals and support a richly decorated archivolt on which traces of original paint survives. Opposite, in the south wall, is a smaller baldachin where the columns themselves are sculpted angels (one with feather tights) standing on lions. Similar sculptures exist in Como and Modena in northern Italy.[88] In addition, the capitals of the columns in the church are all of high artisanal quality, and can be broadly divided into two groups displaying either Classical or Byzantine influences.[84] Apart from its rich Romanesque decoration, Lund Cathedral also contains several late medieval sculptures made by Adam van Düren, as mentioned above. Several of these are of animals and contain inscriptions in Low German. A relief in the south transept displaying the Woman of the Apocalypse flanked by Saint Lawrence and Saint Canute is similar to the portal relief van Düren made a couple of years earlier at Glimmingehus.[89]

Altarpiece

The medieval main altarpiece was donated to the cathedral in 1398 by Ide Pedersdatter Falk.[90] The altarpiece is one of a group of stylistically similar altarpieces and made in some north Germany city, probably by Master Bertram or in his workshop.[91] Its central panel depicts the Coronation of the Virgin, surrounded by two rows of 40 saints, 26 of which are original. Twelve figures have been taken from other medieval altarpieces, while two of the added figures are from the 17th century. The altarpiece is 7.6 metres (25 ft) wide but is missing an original pair of wings.[92][93]

Choir stalls

The choir contains two rows of medieval choir stalls containing in total 78 seats. The wooden stalls date from the end of the 14th century, probably commissioned by archbishop Nils Jönson some time between 1361 and 1379. Clearly made by several different wood carvers, they are approximately 3 metres (9.8 ft) tall without their gables and decorated with carved details. These are biblical scenes from both the Old and New Testament, but the stalls also contain misericords portraying animals and other small details. Their style is High Gothic and they are stylistically linked with contemporary art from the Rhine Valley. They are among the largest wooden Gothic sculptures to survive in the Nordic countries, and have been described as being of internationally high quality.[94] The choir stalls in Lund Cathedral also lent stylistic inspiration to the choir stalls in Roskilde Cathedral and St. Bendt's Church, Ringsted.[94][95]

Slightly older than the choir stalls is a bishop's throne which survives in a damaged state and is placed in the south transept. It is somewhat similar in construction to the choir stalls but stylistically different and more closely related to contemporary art from north Germany.[96] Currently placed next to the bishop's chair is also a Gothic tabernacle in the form of a 5 metres (16 ft) tall, decorated wooden pillar. It contains two cabinets surmounted by a statuette of a female saint and crowned by a hexagonal spire. The tabernacle was repaired by Brunius in the 19th century. The saint may be Ida of Toggenburg.[97]

Astronomical clock

The astronomical clock of Lund Cathedral, presently located at the west end of the north aisle, dates from the late Middle Ages and was installed in Lund Cathedral c. 1425. In 1837, it was dismantled. It was restored at the initiative of architect Theodor Wåhlin and the Danish clockmaker Julius Bertram Larsen and re-inaugurated in 1923. The upper part, which is original, is the clock, while the lower part, a reconstruction, is a calendar. Twice every day the two knights on the top clash their swords. The clock then plays the tune In dulci jubilo and a procession of figures representing the three Kings with their servants parade across the face of the clock.[98] Similar clocks from approximately the same period are known from several churches in towns in the south Baltic Sea area. Especially the clocks in Doberan Minster and St. Nicholas Church, Stralsund are very similar, and it is possible that the clockmaker Nikolaus Lilienfeld who made the clock in Stralsund also made the clock in Lund.[99] The clock was repaired 2009–2010.[37][100][101]

A decorated conventional clock from 1623 is immured on the opposite side of the nave, in the west wall of the south aisle.[54]

Bronzes

The cathedral also owns three High Gothic bronze columns carrying statuettes, the oldest remaining furnishings in the cathedral, and a seven-branched candelabrum from the end of the Middle Ages.[102] Two of the bronze columns are crowned by angels, and the third one by a statuette of Saint Lawrence, holding a gridiron, the symbol of his martyrdom. It probably dates from the middle of the 14th century, while the two angel-bearing columns may be somewhat later. Saint Lawrence's column is approximately 3 metres (9.8 ft) tall (and the saint 70 centimetres (28 in)), while the columns with angels are slightly smaller.[103] The three columns were probably made in Lübeck or Hamburg. Presently located in the south transept is also the 3.5 metres (11 ft) tall seven-branched candelabrum or candle holder from the late 15th century, manufactured by Harmen Bonstede in Hamburg.[104] It was supplied to the cathedral in a dismantled state, and traces of its assembly instruction are still discernible on the candelabrum. Similar candelabra were installed in a number of Scandinavian cathedrals at approximately the same time; although the one in Lund is larger than those in the cathedrals of Aarhus, Ribe, Viborg and Stockholm.[104][105]

Pulpit

The current

Graves and funerary monuments

Several people have been buried in the cathedral. The crypt contains the oldest grave in the cathedral, the grave of Hermann of Schleswig, who played an important role as an emissary of archbishop Ascer of Lund to the Pope and who may have written parts of the aforementioned Necrologium Lundense. The simple Romanesque sarcophagus, which has an inscription in Latin and a depiction of the titular bishop, is located in the apse of the crypt. It dates from the middle of the 12th century.[4][107] The crypt also contains the much larger grave monument of the last archbishop, Birger Gunnersen, which is centrally placed in the crypt. It is of a kind which is not unusual in continental Europe but very unusual in the Nordic countries: a large stone sarcophagus decorated on all sides with sculptures in high relief and with a full-scale depiction of the bishop in full dress on the lid. It was made by Adam van Düren in 1512.[108][109] The cathedral's largest grave monument is that of bishop Hans Brostorp, who died in 1497 and who during his lifetime inaugurated the University of Copenhagen. The monument is made of limestone from Gotland and decorated in low relief.[110]

The nave and the aisles contain several memorial plaques and epitaphs. Several commemorate bishops, such as Johan Engeström (1699–1777) and Nils Hesslén (1728–1811). Many others were made for professors at Lund University, e.g. Eberhard Rosenblad (1714–1796) and Erasmus Sack (1633–1697). The oldest epitaph of the cathedral commemorates the owner of Krageholm Castle Lave Brahe (1500–1567) and his wife Görvel Fadersdotter (Sparre) (1509 or 1517 – 1605).[111]

Baptismal font

The baptismal font of the cathedral is a sparsely decorated Early Gothic font made of reddish grey limestone.[37]

Flora

Several surveys and descriptions of the flora of the cathedral, like the plants that grow on its walls, have been made. The first to describe the flora of the cathedral was Daniel Rolander, one of the apostles of Linnaeus, who made a list of the vascular plants, mosses and lichen he found growing on the building in 1771.[112] It was rediscovered in the 20th century and published in 1931. Elias Magnus Fries also made observations about the flora of the cathedral during the first half of the 19th century. More systematic surveys of the flora of the building have been published in 1922 and in 1993 (the latter only encompassing lichen).[112] Of the species observed growing on the cathedral, the minute fern wall-rue (Asplenium ruta-muraria) was mentioned as early as 1756 by Anders Tidström and is perhaps the most conspicuous member of the cathedral flora.[113] When the lichen flora was surveyed in 1993, 15 species were discovered. One of these, Lecanora perpruinosa, had not been observed in the province of Scania before.[114]

Relationship with Lund University

The founding of

Music

The cathedral has five

There are currently six church organs in Lund Cathedral, including the largest church organ in Sweden. The gallery organ was built between 1932 and 1934 by the Danish company Marcussen & Søn and renovated by the same company in 1992. It has 102 stops distributed between four manuals and a pedalboard. There are 7,074 pipes in total. The smallest organ is inside the astronomical clock, where it plays In dulci jubilo.[120]

References

- ^ "Domkyrkans särskilda skyddshelgon". Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "Lund kn, DOMKYRKAN 1 LUNDS DOMKYRKA". Bebyggelseregistret. Swedish National Heritage Board. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Sundnér 1997, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Rydbeck 1946, p. 48.

- ^ a b Ulvros & Larsson 2012, p. 23.

- ^ Rydén 1998, p. 99–100.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 25.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 25–29.

- ^ Wrangel 1923, p. 4–5.

- ^ Ulvros & Larsson 2012, p. 21.

- ^ Cinthio 1990, p. 1.

- ^ Sundnér 1997, p. 7.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 69–71.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 37.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 38.

- ^ Cinthio 1957, p. 1–42.

- ^ Lindgren 1995, p. 62–64.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 40.

- ^ a b Rydbeck 1946, p. 28.

- ^ Wrangel 1915, p. 4.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 29–30.

- ^ a b c Rydbeck 1946, p. 30.

- ^ Wahlöö 2014, p. 186–187.

- ^ Wrangel 1923, p. 164.

- ^ a b Lindgren 1995, p. 64.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Lindgren 1995, p. 66.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 58.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 59.

- ^ Wrangel 1923, p. 148.

- ^ a b c d e Lindgren 1995, p. 68.

- ^ a b Rydbeck 1946, p. 62.

- ^ Lindgren 1995, p. 79–81.

- ^ Wrangel 1915, p. 265–281.

- ^ Lindgren 1995, p. 90–92.

- ^ Rydbeck 1936, p. 157.

- ^ a b c d e f Wahlöö 2014, p. 187.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 52.

- ^ Lindgren 1995, p. 68–69.

- ^ Lindgren 1995, p. 78.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 74.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 80.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 76.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 76–78.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 80–81.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 86–87.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 90–91.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Sundnér 1997, p. 12.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 88–95.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 100.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 91.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 104.

- ^ a b Rydbeck 1946, p. 126.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 128.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 130.

- ^ Sundnér 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 132.

- ^ a b Rydbeck 1946, p. 134.

- ^ a b c d Rydbeck 1946, p. 135.

- ^ Bodin 2017, p. 121.

- ^ Bodin 2017, p. 121–122.

- ^ Bodin 2017, p. 121–181.

- ^ Bodin 2017, p. 141.

- ^ Bodin 2017, p. 134–141.

- ^ Bodin 2017, p. 142.

- ^ Bodin 2017, p. 142−152.

- ^ Bodin 2017, p. 152.

- ^ Bodin 2017, p. 158–159.

- ^ Sundnér 1997, p. 13–14.

- ^ a b c d "En kyrka i ständig förändring" [A constantly changing church]. Lund Cathedral (official site). Church of Sweden. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Sundnér 1997, p. 14.

- ^ Anderson, Christina (31 October 2016). "Pope Francis, in Sweden, Urges Catholic-Lutheran Reconciliation". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ a b Bodin 2017, p. 181.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 45.

- ^ Ulvros & Larsson 2012, p. 29.

- ^ Ulvros & Larsson 2012, p. 25.

- ^ Bodin 2017, p. 124.

- ^ Lindgren 1995, p. 70–71.

- ^ Lindgren 1995, p. 72–73.

- ^ Bodin 2017, p. 126–127.

- ^ Svanberg 1995, p. 152.

- ^ Ulvros & Larsson 2012, p. 30.

- ^ a b Lindgren 1995, p. 75.

- ^ "Jätten Finn vakar över kryptan" [The giant Finn watches over the crypt]. Lund Cathedral (official site). Church of Sweden. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b Lindgren 1995, p. 77.

- ^ Lindgren 1995, p. 64–65.

- ^ Lindgren 1995, p. 74–75.

- ^ Svanberg 1996, p. 196–197.

- ^ "Gyllene mosaik och korstolar från 1300-talet" [Golden mosaics and choir stalls from the 14th century]. Lund Cathedral (official site). Church of Sweden. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Ulvros & Larsson 2012, p. 70.

- ^ Wrangel 1915, p. 20–23.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 112–113.

- ^ a b Wrangel 1915, p. 24–32.

- ^ Dunér 1984, p. 1–9.

- ^ Wrangel 1915, p. 32–35.

- ^ Wrangel 1915, p. 36–37.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 125–126.

- ^ Schukowski 2008, p. 124–127.

- Sveriges television. 12 October 2009. Archivedfrom the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Det underbara uret i Lund" [The astonishing clock in Lund]. Lund Cathedral (official site). Church of Sweden. Archived from the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Ulvros & Larsson 2012, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 114.

- ^ a b "Vår tids martyrer och den sjuarmade ljusstaken" [The martyrs of our time and the seven-branched candelabrum]. Lund Cathedral (official site). Church of Sweden. Archived from the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 114–116.

- ^ Wrangel 1915, p. 60–64.

- ^ Wrangel 1915, p. 46.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 94.

- ^ Wrangel 1915, p. 48–49.

- ^ Wrangel 1915, p. 47.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 122–125.

- ^ a b Johansson 1993, p. 25.

- ^ Gertz 1923, p. 458.

- ^ Johansson 1993, p. 26.

- ^ "Ett pärlband av händelser" [A string of events]. Lund Cathedral (official site). Church of Sweden. Archived from the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Rydbeck 1946, p. 128–129.

- ^ "Promotionsdagen" [The day of conferment of the doctor's degree]. Lund University. 25 April 2012. Archived from the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ "Körer" [Choirs]. Lund Cathedral (official site). Church of Sweden. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ "Konserter varje vecka" [Concerts every week]. Lund Cathedral (official site). Church of Sweden. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "Sex orglar i Domkyrkan" [Six organs in the cathedral]. Lund Cathedral (official site). Church of Sweden. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

Works cited

- Bodin, Anders (2017). Helgo Zettervalls arkitektur: kyrkor [The architecture of Helgo Zettervall: churches] (PDF) (in Swedish). Vol. II. Stockholm: Carlssons bokförlag. ISBN 978-91-7331-785-6.

- Cinthio, Erik (1957). Lunds domkyrka under romansk tid [Lund Cathedral during the Romanesque era] (PDF) (in Swedish). Lund: C. W. K. Gleerup.

- Cinthio, Erik (1990). "Lunds domkyrkas förhistoria. S:t Laurentiuspatrociniet och Knut den Heliges kyrka än en gång" [The pre-history of Lund Cathedral. The patronage of St. Lawrence and the church of Canute the Holy once more] (PDF). Ale. Historisk Tidskrift för Skåne, Halland och Blekinge (in Swedish). 2: 1–13.

- Dunér, Uno (1984). "Gideon och ullen" [Gideon and the wool] (PDF). Ale. Historisk Tidskrift för Skåne, Halland och Blekinge (in Swedish). 3: 1–10.

- Gertz, Otto (1923). "Vegetationen å ruinerna av Alvastra klosterkyrka" [The vegetation on the ruins of Alvastra monastery church]. Botaniska Notiser (in Swedish): 457–463.

- Johansson, Per (1993). "Lavfloran på Lunds domkyrka" [The lichen flora of Lund Cathedral] (PDF). Svensk Botanisk Tidskrift (in Swedish) (87): 25–30.

- Lindgren, Mereth (1995). "Stenarkitekturen" [The stone architecture]. In Karlsson, Lennart (ed.). Signums svenska konsthistoria. Den romanska konsten [Signum's history of Swedish art. Romanesque art] (in Swedish). Lund: Signum. pp. 299–335. ISBN 91-87896-23-0.

- Rydbeck, Monica (1936). Skånes stenmästare före 1200 [The stone mason masters of Skåne before 1200] (in Swedish). Lund: C. W. K. Gleerups förlag. OCLC 888802816.

- Rydbeck, Otto (1915). Bidrag till Lunds domkyrkas byggnadshistoria [Contributions to the building history of Lund Cathedral]. Lund: C. W. K. Gleerup. OCLC 15548036.

- Rydbeck, Otto (1946). "Lunds domkyrka, byggnadens och dess inventariers historia enligt de nyaste forskningsresultaten" [Lund Cathedral, the history of the building and its furnishings according to the latest research]. In Newman, Ernst (ed.). Lunds domkyrkas historia 1145–1945 [History of Lund Cathedral 1145–1945] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Svenska kyrkans diakonistyrelses bokförlag. OCLC 1163629870.

- Rydén, Thomas (1998). "Lunds domkyrka, det universella rummet" [Lund Cathedral, the universal space]. In Wahlöö, Claes (ed.). Metropolis Daniae: ett stycke Europa [Metropolis Daniae: a piece of Europe] (PDF) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Lund University. )

- Schukowski, Manfred (2008). "Astronomiska ur i Hansatidens kyrkor" [Astronomical clocks in the churches of the Hanseatic era]. In Mogensen, Lone (ed.). Det underbara uret i Lund [The wonderful clock in Lund] (in Swedish). Lund: Historiska Media. ISBN 978-91-85507-93-1.

- Sundnér, Barbro (1997). "Byggnadshistoria" [Building history]. In Löfvendahl, Runo; Sundnér, Barbro (eds.). Lunds domkyrka: stenmaterial och skadebild [Lund Cathedral: stone material and damages] (PDF) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Riksantikvarieämbetet (ISBN 91-7209-006-5.

- Svanberg, Jan (1995). "Stenskulpturen" [The stone sculpture]. In Karlsson, Lennart (ed.). Signums svenska konsthistoria. Den romanska konsten [Signum's history of Swedish art. Romanesque art] (in Swedish). Lund: Signum. pp. 299–335. ISBN 91-87896-23-0.

- Svanberg, Jan (1996). "Stenskulpturen" [The stone sculpture]. In Augustsson, Jan-Erik (ed.). Signums svenska konsthistoria. Den gotiska konsten [Signum's history of Swedish art. Gothic art] (in Swedish). Lund: Signum. pp. 299–335. ISBN 91-87896-23-0.

- Ulvros, Eva Helen; Larsson, Anita (2012). Dokyrkan i Lund [The cathedral in Lund] (in Swedish). Lund: Historiska Media. ISBN 978-91-87031-34-2.

- Wahlöö, Claes (2014). Skånes kyrkor 1050-1949 [The churches of Skåne 1050–1949] (in Swedish). Kävlinge: Domus Propria. ISBN 978-91-637-5874-4.

- Wrangel, Ewert (1915). Konstverk i Lunds domkyrka [Art in Lund Cathedral]. Lund: C. W. K. Gleerup. OCLC 84313403.

- Wrangel, Ewert (1923). Lunds domkyrkas konsthistoria: förbindelser och stilfränder [The art history of Lund Cathedral: connections and stylistic equals]. Lund: C. W. K. Gleerup. OCLC 250557100.

Further reading

- Brunius, Carl Georg (1836). Nordens äldsta metropolitankyrka, eller, historisk och arkitektonisk beskrifning öfver Lunds domkyrka [The oldest metropolitan church in the Nordic countries, or, historic and architectonic description of Lund Cathedral] (in Swedish). Lund: Berling. OCLC 69415972.

- Gierow, Krister (1946). Lunds domkyrka i litteraturen: bibliografisk förteckning [Lund Cathedral in literature: a bibliography] (in Swedish). Lund: C. W. K. Gleerup. OCLC 186895962.

- Zettervall, Helgo (1916). "Helgo Zettervall om Lunds domkyrka: en byggnadsbeskrivning i brev" [Helgo Zettervall on Lund Cathedral: description of a building in letters]. Historisk tidskrift för Skåneland (in Swedish). 6. Lund: 412–421. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

External links

Media related to Lund Cathedral at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lund Cathedral at Wikimedia Commons- Official website of the cathedral

- Digitised copy of the Necrologium Lundense, with information about the book and its contents in English

- Digitised copy of the Liber daticus vetustior, with information about the book and its contents in English

- YouTube channel of the cathedral