LSD

Skeletal formula of LSD | |

Ball-and-stick model of LSD | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /daɪ eθəl ˈæmaɪd/, /æmɪd/, or /eɪmaɪd/[1][2][3] |

| Trade names | Delysid |

| Other names | LSD, LSD-25, LAD, Acid, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Reference |

| Pregnancy category |

|

psychedelic) | |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 80 to 85 °C (176 to 185 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 67.02[11] mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Lysergic acid diethylamide, commonly known as LSD (from German Lysergsäure-diethylamid), and known colloquially as acid or lucy, is a potent psychedelic drug.[12] Effects typically include intensified thoughts, emotions, and sensory perception.[13] At sufficiently high dosages, LSD manifests primarily mental, visual, and auditory hallucinations.[14][15] Dilated pupils, increased blood pressure, and increased body temperature are typical.[16]

Effects typically begin within half an hour and can last for up to 20 hours (although on average, experiences last 8–12 hours).

LSD is pharmacologically considered to be non-addictive with a low potential for abuse. Adverse psychological reactions are possible, such as

LSD is structurally related to

The effects of LSD are thought to stem primarily from it being an

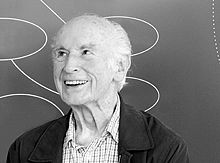

Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann first synthesized LSD in 1938 from lysergic acid, a chemical derived from the hydrolysis of ergotamine, an alkaloid found in ergot, a fungus that infects grain.[16][20] LSD was the 25th of various lysergamides Hofmann synthesized from lysergic acid while trying to develop a new analeptic, hence the alternate name LSD-25. Hofmann discovered its effects in humans in 1943, after unintentionally ingesting an unknown amount, possibly absorbing it through his skin.[30][31][32] LSD was subject to exceptional interest within the field of psychiatry in the 1950s and early 1960s, with Sandoz distributing LSD to researchers under the trademark name Delysid in an attempt to find a marketable use for it.[31]

LSD-assisted

In the 1960s, LSD and other psychedelics were adopted by, and became synonymous with, the

Uses

Recreational

LSD is commonly used as a recreational drug.[39]

Spiritual

LSD can catalyze intense spiritual experiences and is thus considered an

Medical

LSD currently has no approved uses in

Effects

LSD is exceptionally potent, with as little as 20 μg capable of producing a noticeable effect.[16]

Physical

LSD can induce physical effects such as

Psychological

The primary immediate psychological effects of LSD are

Conversely, negative experiences, known as "bad trips," can induce feelings of fear, anxiety, panic, paranoia, and even suicidal ideation.[54] While the occurrence of a bad trip is unpredictable, factors such as mood, surroundings, sleep, hydration, and social setting, collectively referred to as "set and setting", can influence the risk and are considered important in minimizing the likelihood of a negative experience.[55][56]

Sensory

LSD induces an animated sensory experience affecting senses, emotions, memories, time, and awareness, lasting from 6 to 20 hours, with the duration dependent on dosage and individual tolerance. Effects typically commence within 30 to 90 minutes post-ingestion, ranging from subtle perceptual changes to profound cognitive shifts. Alterations in auditory and visual perception are common.[57][58]

Users may experience enhanced visual phenomena, such as vibrant colors, objects appearing to morph, ripple or move, and geometric patterns on various surfaces. Changes in the perception of food's texture and taste are also noted, sometimes leading to aversion towards certain foods.[57][59]

There are reports of inanimate objects appearing animated, with static objects seeming to move in additional spatial dimensions.

Adverse effects

LSD, a classical psychedelic, is deemed physiologically safe at standard dosages (50–200 μg) and its primary risks lie in psychological effects rather than physiological harm.[25][63] A 2010 study by David Nutt ranked LSD as significantly less harmful than alcohol, placing it near the bottom of a list assessing the harm of 20 drugs.[64]

Psychological effects

Mental disorders

LSD can induce

Suggestibility

While research from the 1960s indicated increased suggestibility under the influence of LSD among both mentally ill and healthy individuals, recent documents suggest that the CIA and Department of Defense have discontinued research into LSD as a means of mind control.[68][69][70][non-primary source needed]

Flashbacks

Flashbacks are psychological episodes where individuals re-experience some of LSD's subjective effects after the drug has worn off, persisting for days or months post-hallucinogen use.[71][72] These experiences are associated with hallucinogen persisting perception disorder, where flashbacks occur intermittently or chronically, causing distress or functional impairment.[21]

The etiology of flashbacks is varied. Some cases are attributed to somatic symptom disorder, where individuals fixate on normal somatic experiences previously unnoticed prior to drug consumption.[73] Other instances are linked to associative reactions to contextual cues, similar to responses observed in individuals with past trauma or emotional experiences.[74] The risk factors for flashbacks remain unclear, but pre-existing psychopathologies may be significant contributors.[75]

Estimating the prevalence of

Drug-interactions

Several psychedelics, including LSD, are metabolized by

Fatal dose

Lethal oral dose of LSD in humans is estimated at 100 mg, based on LD50 and lethal blood concentrations observed in rodent studies.[63]

Tolerance

LSD shows significant

Addiction and dependence liability

The

Cancer and pregnancy

The

Overdose

There have been no documented fatal human overdoses from LSD,[7][93] although there has been no "comprehensive review since the 1950s" and "almost no legal clinical research since the 1970s".[7] Eight individuals who had accidentally consumed an exceedingly high amount of LSD, mistaking it for cocaine, had plasma levels of 1000–7000 μg per 100 mL blood plasma had suffered from comatose states, vomiting, respiratory problems, hyperthermia, and light gastrointestinal bleeding; however, all of them survived without residual effects upon hospital intervention.[7]

Individuals experiencing a bad trip after LSD intoxication may be presented with severe anxiety, tachycardia, often accompanied by phases of psychotic agitation and varying degrees of delusions.[63] Cases of death on a bad trip have been reported due to prone maximal restraint (PMR) and positional asphyxia when the individuals were held restraint by law enforcement personnel.[63]

Massive doses are largely managed by

Designer drug overdose

Many

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Receptor | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 1.1 |

| 5-HT2A | 2.9 |

| 5-HT2B | 4.9 |

| 5-HT2C | 23 |

| 5-HT5A | 9 |

| 5-HT6 | 2.3 |

Most

LSD binds to most serotonin receptor subtypes except for the 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors. However, most of these receptors are affected at too low affinity to be sufficiently activated by the brain concentration of approximately 10–20 nM.[25] In humans, recreational doses of LSD can affect 5-HT1A (Ki = 1.1 nM), 5-HT2A (Ki = 2.9 nM), 5-HT2B (Ki = 4.9 nM), 5-HT2C (Ki = 23 nM), 5-HT5A (Ki = 9 nM [in cloned rat tissues]), and 5-HT6 receptors (Ki = 2.3 nM).[107] Although not present in humans, 5-HT5B receptors found in rodents also have a high affinity for LSD.[108] The psychedelic effects of LSD are attributed to cross-activation of 5-HT2A receptor heteromers.[109] Many but not all 5-HT2A agonists are psychedelics and 5-HT2A antagonists block the psychedelic activity of LSD. LSD exhibits functional selectivity at the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors in that it activates the signal transduction enzyme phospholipase A2 instead of activating the enzyme phospholipase C as the endogenous ligand serotonin does.[110]

Exactly how LSD produces its effects is unknown, but it is thought that it works by increasing

LSD is a

Pharmacokinetics

The acute effects of LSD normally last between 6 and 10 hours depending on dosage, tolerance, and age.[117][118] Aghajanian and Bing (1964) found LSD had an elimination half-life of only 175 minutes (about 3 hours).[107] However, using more accurate techniques, Papac and Foltz (1990) reported that 1 µg/kg oral LSD given to a single male volunteer had an apparent plasma half-life of 5.1 hours, with a peak plasma concentration of 5 ng/mL at 3 hours post-dose.[119]

The

The effects of the dose of LSD given lasted for up to 12 hours and were closely correlated with the concentrations of LSD present in circulation over time, with no acute

Mechanisms of action

Neuroimaging studies using

Chemistry

LSD is a

However, LSD and iso-LSD, the two C-8 isomers, rapidly interconvert in the presence of bases, as the alpha proton is acidic and can be deprotonated and reprotonated. Non-psychoactive iso-LSD which has formed during the synthesis can be separated by chromatography and can be isomerized to LSD.

Pure salts of LSD are

Synthesis

LSD is an

Research

The precursor for LSD,

Dosage

A single dose of LSD may be between 40 and 500 micrograms—an amount roughly equal to one-tenth the mass of a grain of sand. Threshold effects can be felt with as little as 25 micrograms of LSD.

In the mid-1960s, the most important black market LSD manufacturer (Owsley Stanley) distributed LSD at a standard concentration of 270 µg,[132] while street samples of the 1970s contained 30 to 300 µg. By the 1980s, the amount had reduced to between 100 and 125 µg, dropping more in the 1990s to the 20–80 µg range,[133] and even more in the 2000s (decade).[132][134]

Reactivity and degradation

"LSD," writes the chemist Alexander Shulgin, "is an unusually fragile molecule ... As a salt, in water, cold, and free from air and light exposure, it is stable indefinitely."[117]

LSD has two

LSD also has

A controlled study was undertaken to determine the stability of LSD in pooled urine samples.[135] The concentrations of LSD in urine samples were followed over time at various temperatures, in different types of storage containers, at various exposures to different wavelengths of light, and at varying pH values. These studies demonstrated no significant loss in LSD concentration at 25 °C for up to four weeks. After four weeks of incubation, a 30% loss in LSD concentration at 37 °C and up to a 40% at 45 °C were observed. Urine fortified with LSD and stored in amber glass or nontransparent polyethylene containers showed no change in concentration under any light conditions. Stability of LSD in transparent containers under light was dependent on the distance between the light source and the samples, the wavelength of light, exposure time, and the intensity of light. After prolonged exposure to heat in alkaline pH conditions, 10 to 15% of the parent LSD epimerized to iso-LSD. Under acidic conditions, less than 5% of the LSD was converted to iso-LSD. It was also demonstrated that trace amounts of metal ions in buffer or urine could catalyze the decomposition of LSD and that this process can be avoided by the addition of

Detection

LSD can be detected in concentrations larger than approximately 10% in a sample using

LSD may be quantified in urine for drug abuse testing programs, in plasma or serum to confirm poisoning in hospitalized victims, or in whole blood for forensic investigations. The parent drug and its major metabolite are unstable in biofluids when exposed to light, heat, or alkaline conditions, necessitating protection from light, low-temperature storage, and quick analysis to minimize losses.[137] Maximum plasma concentrations are typically observed 1.4 to 1.5 hours after oral administration of 100 µg and 200 µg, respectively, with a plasma half-life of approximately 2.6 hours (ranging from 2.2 to 3.4 hours among test subjects).[138]

Due to its potency in microgram quantities, LSD is often not included in standard pre-employment urine or hair analyses.[136][139] However, advanced liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry methods can detect LSD in biological samples even after a single use.[139]

History

... affected by a remarkable restlessness, combined with a slight dizziness. At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors. After some two hours this condition faded away.

—Albert Hofmann, on his first experience with LSD[140]: 15

LSD was first synthesized on November 16, 1938[141] by Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann at the Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland as part of a large research program searching for medically useful ergot alkaloid derivatives. The abbreviation "LSD" is from the German "Lysergsäurediethylamid".[142]

LSD's

Beginning in the 1950s, the US

In 1963, the Sandoz patents on LSD expired[133] and the Czech company Spofa began to produce the substance.[30] Sandoz stopped the production and distribution in 1965.[30]

Several figures, including Aldous Huxley, Timothy Leary, and Al Hubbard, had begun to advocate the consumption of LSD. LSD became central to the counterculture of the 1960s.[147] In the early 1960s the use of LSD and other hallucinogens was advocated by new proponents of consciousness expansion such as Leary, Huxley, Alan Watts and Arthur Koestler,[148][149] and according to L. R. Veysey they profoundly influenced the thinking of the new generation of youth.[150]

On October 24, 1968, possession of LSD was made illegal in the United States.[151] The last FDA approved study of LSD in patients ended in 1980, while a study in healthy volunteers was made in the late 1980s. Legally approved and regulated psychiatric use of LSD continued in Switzerland until 1993.[152]

In November 2020, Oregon became the first US state to decriminalize possession of small amounts of LSD after voters approved

Society and culture

Counterculture

By the mid-1960s, the youth countercultures in California, particularly in San Francisco, had widely adopted the use of hallucinogenic drugs, including LSD. The first major underground LSD factory was established by Owsley Stanley.[154] Around this time, the Merry Pranksters, associated with novelist Ken Kesey, organized the Acid Tests, events in San Francisco involving LSD consumption, accompanied by light shows and improvised music.[155][156] Their activities, including cross-country trips in a psychedelically decorated bus and interactions with major figures of the beat movement, were later documented in Tom Wolfe's The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968).[157]

In San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, the Psychedelic Shop was opened in January 1966 by brothers Ron and Jay Thelin to promote safe use of LSD. This shop played a significant role in popularizing LSD in the area and establishing Haight-Ashbury as the epicenter of the hippie counterculture. The Thelins also organized the Love Pageant Rally in Golden Gate Park in October 1966, protesting against California's ban on LSD.[158][159]

A similar movement developed in London, led by British academic

Music and Art

The influence of LSD in the realms of music and art became pronounced in the 1960s, especially through the Acid Tests and related events involving bands like the

In the United Kingdom, Michael Hollingshead, reputed for introducing LSD to various artists and musicians like Storm Thorgerson, Donovan, Keith Richards, and members of the Beatles, played a significant role in the drug's proliferation in the British art and music scene. Despite LSD's illegal status from 1966, it was widely used by groups including the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Moody Blues. Their experiences influenced works such as the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band and Cream's Disraeli Gears, featuring psychedelic-themed music and artwork.[162]

Psychedelic music of the 1960s often sought to replicate the LSD experience, incorporating exotic instrumentation, electric guitars with effects pedals, and elaborate studio techniques. Artists and bands utilized instruments like sitars and tablas, and employed studio effects such as backwards tapes, panning, and phasing.[163][164] Songs such as John Prine's "Illegal Smile" and the Beatles' "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" have been associated with LSD, although the latter's authors denied such claims.[165][page needed][166]

Contemporary artists influenced by LSD include Keith Haring in the visual arts,[167] various electronic dance music creators,[168] and the jam band Phish.[169] The 2018 Leo Butler play All You Need is LSD is inspired by the author's interest in the history of LSD.[170]

Legal status

The United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 mandates that signing parties, including the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and most of Europe, prohibit LSD. Enforcement of these laws varies by country. The convention allows medical and scientific research with LSD.[171]

Australia

In Australia, LSD is classified as a Schedule 9 prohibited substance under the Poisons Standard (February 2017), indicating it may be abused or misused and its manufacture, possession, sale, or use should be prohibited except for approved research purposes.[172] In Western Australia, the Misuse of Drugs Act 1981 provides guidelines for possession and trafficking of substances like LSD.[173]

Canada

In Canada, LSD is listed under Schedule III of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Unauthorized possession and trafficking of the substance can lead to significant legal penalties.[54]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, LSD is a Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, making unauthorized possession and trafficking punishable by severe penalties. The Runciman Report and Transform Drug Policy Foundation have made recommendations and proposals regarding the legal regulation of LSD and other psychedelics.[174][175]

United States

In the United States, LSD is classified as a Schedule I controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, making its manufacture, possession, and distribution illegal without a DEA license. The law considers LSD to have a high potential for abuse, no legitimate medical use, and to be unsafe even under medical supervision. The US Supreme Court case Neal v. United States (1995) clarified the sentencing guidelines related to LSD possession.[176]

Oregon decriminalized personal possession of small amounts of drugs, including LSD, in February 2021, and California has seen legislative efforts to decriminalize psychedelics.[177]

Mexico

Mexico decriminalized the possession of small amounts of drugs, including LSD, for personal use in 2009. The law specifies possession limits and establishes that possession is not a crime within designated quantities.[178]

Czech Republic

In the Czech Republic, possession of "amount larger than small" of LSD is criminalized, while possession of smaller amounts is a misdemeanor. The definition of "amount larger than small" is determined by judicial practice and specific regulations.[179][180]

Economics

Production

An active dose of LSD is very minute, allowing a large number of doses to be synthesized from a comparatively small amount of raw material. Twenty five kilograms of precursor ergotamine tartrate can produce 5–6 kg of pure crystalline LSD; this corresponds to around 50–60 million doses at 100 µg. Because the masses involved are so small, concealing and transporting illicit LSD is much easier than smuggling cocaine, cannabis, or other illegal drugs.[181]

Manufacturing LSD requires laboratory equipment and experience in the field of organic chemistry. It takes two to three days to produce 30 to 100 grams of pure compound. It is believed that LSD is not usually produced in large quantities, but rather in a series of small batches. This technique minimizes the loss of precursor chemicals in case a step does not work as expected.[181]

Forms

LSD is produced in crystalline form and is then mixed with excipients or redissolved for production in ingestible forms. Liquid solution is either distributed in small vials or, more commonly, sprayed onto or soaked into a distribution medium. Historically, LSD solutions were first sold on sugar cubes, but practical considerations forced a change to tablet form. Appearing in 1968 as an orange tablet measuring about 6 mm across, "Orange Sunshine" acid was the first largely available form of LSD after its possession was made illegal. Tim Scully, a prominent chemist, made some of these tablets, but said that most "Sunshine" in the USA came by way of Ronald Stark, who imported approximately thirty-five million doses from Europe.[182]

Over a period of time, tablet dimensions, weight, shape and concentration of LSD evolved from large (4.5–8.1 mm diameter), heavyweight (≥150 mg), round, high concentration (90–350 µg/tab) dosage units to small (2.0–3.5 mm diameter) lightweight (as low as 4.7 mg/tab), variously shaped, lower concentration (12–85 µg/tab, average range 30–40 µg/tab) dosage units. LSD tablet shapes have included cylinders, cones, stars, spacecraft, and heart shapes. The smallest tablets became known as "Microdots."[183]

After tablets came "computer acid" or "blotter paper LSD," typically made by dipping a preprinted sheet of blotting paper into an LSD/water/alcohol solution.[182][183] More than 200 types of LSD tablets have been encountered since 1969 and more than 350 blotter paper designs have been observed since 1975.[183] About the same time as blotter paper LSD came "Windowpane" (AKA "Clearlight"), which contained LSD inside a thin gelatin square a quarter of an inch (6 mm) across.[182] LSD has been sold under a wide variety of often short-lived and regionally restricted street names including Acid, Trips, Uncle Sid, Blotter, Lucy, Alice and doses, as well as names that reflect the designs on the sheets of blotter paper.[52][184] Authorities have encountered the drug in other forms—including powder or crystal, and capsule.[185]

Modern distribution

LSD manufacturers and traffickers in the United States can be categorized into two groups: A few large-scale producers, and an equally limited number of small, clandestine chemists, consisting of independent producers who, operating on a comparatively limited scale, can be found throughout the country.[186][187]

As a group, independent producers are of less concern to the Drug Enforcement Administration than the large-scale groups because their product reaches only local markets.[145]

Many LSD dealers and chemists describe a religious or humanitarian purpose that motivates their illicit activity. Nicholas Schou's book Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love, and Acid to the World describes one such group, the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. The group was a major American LSD trafficking group in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[188]

In the second half of the 20th century, dealers and chemists loosely associated with the

Mimics

Since 2005, law enforcement in the United States and elsewhere has seized several chemicals and combinations of chemicals in blotter paper which were sold as LSD mimics, including

Research

In the United States the earliest research began in the 1950s. Albert Kurland and his colleagues published research on LSD's therapeutic potential to treat schizophrenia. In Canada, Humphrey Osmond and Abram Hoffer completed LSD studies as early as 1952.[200] By the 1960s, controversies surrounding "hippie" counterculture began to deplete institutional support for continued studies.

Currently, a number of organizations—including the Beckley Foundation, MAPS, Heffter Research Institute and the Albert Hofmann Foundation—exist to fund, encourage and coordinate research into the medicinal and spiritual uses of LSD and related psychedelics.[201] New clinical LSD experiments in humans started in 2009 for the first time in 35 years.[202] As it is illegal in many areas of the world, potential medical uses are difficult to study.[43]

In 2001 the

A 2020 meta-review indicated possible positive effects of LSD in reducing psychiatric symptoms, mainly in cases of alcoholism.[206] There is evidence that psychedelics induce molecular and cellular adaptations related to neuroplasticity and that these could potentially underlie therapeutic benefits.[207][208]

Psychedelic therapy

In the 1950s and 1960s, LSD was used in psychiatry to enhance psychotherapy, known as psychedelic therapy. Some psychiatrists, such as Ronald A. Sandison, who pioneered its use at Powick Hospital in England, believed LSD was especially useful at helping patients to "unblock" repressed subconscious material through other psychotherapeutic methods,[209] and also for treating alcoholism.[210][211] One study concluded, "The root of the therapeutic value of the LSD experience is its potential for producing self-acceptance and self-surrender,"[34] presumably by forcing the user to face issues and problems in that individual's psyche.

Two recent reviews concluded that conclusions drawn from most of these early trials are unreliable due to serious

In recent years, organizations like the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies have renewed clinical research of LSD.[202]

It has been proposed that LSD be studied for use in the therapeutic setting, particularly in anxiety.[45][46][214][215]

Other uses

In the 1950s and 1960s, some psychiatrists (e.g. Oscar Janiger) explored the potential effect of LSD on creativity. Experimental studies attempted to measure the effect of LSD on creative activity and aesthetic appreciation.[53][216][217][218] In 1966 Dr. James Fadiman conducted a study with the central question "How can psychedelics be used to facilitate problem solving?" This study attempted to solve 44 different problems and had 40 satisfactory solutions when the FDA banned all research into psychedelics. LSD was a key component of this study.[219][220]

Since 2008 there has been ongoing research into using LSD to alleviate anxiety for terminally ill cancer patients coping with their impending deaths.[45][202][221]

A 2012 meta-analysis found evidence that a single dose of LSD in conjunction with various alcoholism treatment programs was associated with a decrease in alcohol abuse, lasting for several months, but no effect was seen at one year. Adverse events included seizure, moderate confusion and agitation, nausea, vomiting, and acting in a bizarre fashion.[35]

LSD has been used as a treatment for cluster headaches with positive results in some small studies.[7]

Recently, researchers discovered that LSD is a potent

LSD may have analgesic properties related to pain in terminally ill patients and phantom pain and may be useful for treating inflammatory diseases including rheumatoid arthritis.[224]

Notable individuals

Some notable individuals have commented publicly on their experiences with LSD.

- W. H. Auden, the poet, said, "I myself have taken mescaline once and L.S.D. once. Aside from a slight schizophrenic dissociation of the I from the Not-I, including my body, nothing happened at all."[227] He also said, "LSD was a complete frost. … What it does seem to destroy is the power of communication. I have listened to tapes done by highly articulate people under LSD, for example, and they talk absolute drivel. They may have seen something interesting, but they certainly lose either the power or the wish to communicate."[228] He also said, "Nothing much happened but I did get the distinct impression that some birds were trying to communicate with me."[229]

- Daniel Ellsberg, an American peace activist, says he has had several hundred experiences with psychedelics.[230]

- Richard Feynman, a notable physicist at California Institute of Technology, tried LSD during his professorship at Caltech. Feynman largely sidestepped the issue when dictating his anecdotes; he mentions it in passing in the "O Americano, Outra Vez" section.[231][232]

- Relix Magazine, in response to the question "Have your feelings about LSD changed over the years?," "They haven't changed much. My feelings about LSD are mixed. It's something that I both fear and that I love at the same time. I never take any psychedelic, have a psychedelic experience, without having that feeling of, "I don't know what's going to happen." In that sense, it's still fundamentally an enigma and a mystery."[233]

- Bill Gates implied in an interview with Playboy that he tried LSD during his youth.[234]

- Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World, became a user of psychedelics after moving to Hollywood. He was at the forefront of the counterculture's use of psychedelic drugs, which led to his 1954 work The Doors of Perception. Dying from cancer, he asked his wife on 22 November 1963 to inject him with 100 µg of LSD. He died later that day.[235]

- Steve Jobs, co-founder and former CEO of Apple Inc., said, "Taking LSD was a profound experience, one of the most important things in my life."[236]

- Ernst Jünger, German writer and philosopher, throughout his life had experimented with drugs such as ether, cocaine, and hashish; and later in life he used mescaline and LSD. These experiments were recorded comprehensively in Annäherungen (1970, Approaches). The novel Besuch auf Godenholm (1952, Visit to Godenholm) is clearly influenced by his early experiments with mescaline and LSD. He met with LSD inventor Albert Hofmann and they took LSD together several times. Hofmann's memoir LSD, My Problem Child describes some of these meetings.[237]

- In a 2004 interview, Paul McCartney said that The Beatles' songs "Day Tripper" and "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" were inspired by LSD trips.[165]: 182 Nonetheless, John Lennon consistently stated over the course of many years that the fact that the initials of "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" spelled out L-S-D was a coincidence (he stated that the title came from a picture drawn by his son Julian) and that the band members did not notice until after the song had been released, and Paul McCartney corroborated that story.[238] John Lennon, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr also used the drug, although McCartney cautioned that "it's easy to overestimate the influence of drugs on the Beatles' music."[239]

- Michel Foucault had an LSD experience with Simeon Wade in the Death Valley and later wrote "it was the greatest experience of his life, and that it profoundly changed his life and his work."[240][241] According to Wade, as soon as he came back to Paris, Foucault scrapped the second History of Sexuality's manuscript, and totally rethought the whole project.[242]

- Kary Mullis is reported to credit LSD with helping him develop DNA amplification technology, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993.[243]

- Carlo Rovelli, an Italian theoretical physicist and writer, has credited his use of LSD with sparking his interest in theoretical physics.[244]

- neurologist famous for writing best-selling case histories about his patients' disorders and unusual experiences, talks about his own experiences with LSD and other perception altering chemicals, in his book, Hallucinations.[245]

- Matt Stone and Trey Parker, creators of the TV series South Park, claimed to have shown up at the 72nd Academy Awards, at which they were nominated for Best Original Song, under the influence of LSD.[246]

See also

- 1P-LSD

- 1cP-LSD

- Claviceps purpurea (ergot)

- Ergotamine

- Lisuride

- LSD art

- LSZ

- Lysergic acid

- Owsley Stanley

- Psychedelic microdosing

- Psychedelic therapy

- Psychoplastogen

- Urban legends about LSD

Notes

- ^ Although cross-tolerance to DMT is noted as negligible,[84] some reports suggest that LSD-tolerant individuals showed undiminished responses to DMT.[85]

- ^ The potency of N-benzylphenethylamines via buccal, sublingual, or nasal absorption is 50–100 greater (by weight) than oral route compared to the parent 2C-x compounds.[101] Researches hypothesize the low oral metabolic stability of N-benzylphenethylamines is likely causing the low bioavailability on the oral route, although the metabolic profile of this compounds remains unpredictable; therefore researches state that the fatalities linked to these substances may partly be explained by differences in the metabolism between individuals.[101]

References

- ^ "Definition of "amide"". Collins English Dictionary. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ "American Heritage Dictionary Entry: amide". Ahdictionary.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ "amide – definition of amide in English from the Oxford Dictionary". Oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ISBN 978-3-642-27772-6.

Hallucinogen abuse and dependence are known complications resulting from ... LSD and psilocybin. Users do not experience withdrawal symptoms, but the general criteria for substance abuse and dependence otherwise apply. Dependence is estimated in approximately 2 % of recent-onset users

- ^ ISBN 9780071481274.

Several other classes of drugs are categorized as drugs of abuse but rarely produce compulsive use. These include psychedelic agents, such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)

- ^ PMID 26108222.

- ^ PMID 19040555.

- ISBN 9780781792561. Archivedfrom the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ PMID 27392130.

- ISBN 9781585626632. Archivedfrom the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Lysergide". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ PMID 26841800.

- ^ a b c "What are hallucinogens?". National Institute of Drug Abuse. January 2016. Archived from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- PMID 32944778.

Thalamocortical connectivity was found altered in psychedelic states. Specifically, LSD was found to selectively increase effective connectivity from the thalamus to certain DMN areas, while other connections are attenuated. Furthermore, increased thalamic connectivity with the right fusiform gyrus and the anterior insula correlated with visual and auditory hallucinations (AH), respectively.

- ^ PMID 33059356.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "LSD profile (chemistry, effects, other names, synthesis, mode of use, pharmacology, medical use, control status)". EMCDDA. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- ^ Sloat S (January 27, 2017). "This is Why You Can't Escape an Hours-Long Acid Trip". Inverse. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- PMID 27714429.

- ^ Gershon L (July 19, 2016). "How LSD Went From Research to Religion". JSTOR Daily. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Commonly Abused Drugs Charts". National Institute on Drug Abuse. July 2, 2018. Archived from the original on March 1, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- ^ PMID 27822679.

- S2CID 261098164.

- doi:10.1071/CH23050.

- PMID 35487983.

- ^ PMID 14761703.

- S2CID 233346402.

- ^ PMID 27071089.

- ^ PMID 24309097.

- ^ S2CID 23565306.

- ^ OCLC 610059315.

- ^ OCLC 25281992.

- ISBN 978-1-351-97870-5. Archivedfrom the original on September 27, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ "Psychiatric Research with Hallucinogens". www.druglibrary.org. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ PMID 13810249.

- ^ S2CID 10677273.

- ^ United States Congress House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce Subcommittee on Public Health and Welfare (1968). Increased Controls Over Hallucinogens and Other Dangerous Drugs. U.S. Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ National Institute on Drug Abuse. "Hallucinogens". Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- S2CID 218893155.

- ^ "DrugFacts: Hallucinogens – LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP". National Institute on Drug Abuse. December 2014. Archived from the original on February 16, 2015. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-59884-478-8.

- ^ San Francisco Chronicle September 20, 1966 Page One

- ISBN 978-0-285-64882-1. Archived from the originalon October 18, 2007. Retrieved November 18, 2007.

- ^ S2CID 1956833.

- ^ Campbell D (July 23, 2016). "Scientists study possible health benefits of LSD and ecstasy | Science". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 23, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c Lustberg D (October 14, 2022). "Acid for Anxiety: Fast and Lasting Anxiolytic Effects of LSD". Psychedelic Science Review. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ S2CID 252095586.

- PMID 27354908.

- ^ "History of LSD Therapy". druglibrary.org. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ "Hallucinogens – LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP". NIDA InfoFacts. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). June 2009. Archived from the original on November 21, 2009.

- PMID 17149427.

- S2CID 16483172.

- ^ a b Honig D. "Frequently Asked Questions". Erowid. Archived from the original on February 12, 2016.

- ^ PMID 6054248. Archived from the original(PDF) on April 30, 2011.

- ^ a b Canadian government (1996). "Controlled Drugs and Substances Act". Justice Laws. Canadian Department of Justice. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ Rogge T (May 21, 2014), Substance use – LSD, MedlinePlus, U.S. National Library of Medicine, archived from the original on July 28, 2016, retrieved July 14, 2016

- ^ CESAR (October 29, 2013), LSD, Center for Substance Abuse Research, University of Maryland, archived from the original on July 15, 2016, retrieved July 14, 2016

- ^ .

- PMID 5639999.

- PMID 8888996.

- ^ Oster G (1966). "Moiré patterns and visual hallucinations" (PDF). Psychedelic Review. 7: 33–40. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 19, 2017.

- S2CID 24037275.

- S2CID 5903121.

- ^ PMID 29408722.

- S2CID 5667719.

- PMID 23976938.

- S2CID 205326399

- ^ "LSD". TOXNET – Toxicology Data Network – HSDB Database. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on March 22, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ Rockefeller IV JD (December 8, 1994). "Is Military Research Hazardous to Veterans Health? Lessons Spanning Half A Century, part F. HALLUCINOGENS". West Virginia: 103rd Congress, 2nd Session-S. Prt. 103-97; Staff Report prepared for the committee on veterans' affairs. Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- S2CID 19439549. Archived from the original(PDF) on April 30, 2011.

- S2CID 15249061.

- PMID 12609692.

- S2CID 246276633.

- S2CID 2025731.

- ISBN 978-3-86135-207-5.

- S2CID 7587687.

- ^ ISBN 9780192678522.

- PMID 35981469.

- PMID 4962683.

- ISBN 978-0-12-800212-4.

- ^ PMID 28701958.

- S2CID 255470638.

- S2CID 23803624. Archived from the originalon April 19, 2014. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- S2CID 7746880. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- S2CID 32950588.

- S2CID 3220559.

- S2CID 11768927.

- S2CID 35508993.

- ^ PMID 17105338.

- PMID 13796178.

- PMID 29366418.

- PMID 7987187.

- PMID 9862186.

- ^ S2CID 247888583.

- ^ a b c d LSD Toxicity Treatment & Management~treatment at eMedicine

- PMID 32174803.

- S2CID 53373205.

- ^ PMID 30261175.

- PMID 26378135.

- ^ S2CID 247764056.

- PMID 31915427.

- ^ S2CID 254857910.

- PMID 28097528.

- PMID 27406128.

- PMID 25105138.

- S2CID 240583877.

- ^ a b "Lysergide (LSD) drug profile". European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). Archived from the original on February 2, 2023. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ S2CID 29438767. Archived from the original(PDF) on March 27, 2009.

- PMID 14965244.

- PMID 21276828.

- S2CID 447937.

- PMID 10432484.

- PMID 16353915.

- PMID 23536.

- ^ PMID 12213075.

- ^ PMID 28129534.

- ^ PMID 28129538.

- ^ ISBN 0-9630096-9-9. Archived from the originalon October 15, 2008.

- PMID 19040555.

- from the original on April 29, 2011.

- PMID 36192411.

- S2CID 257862535.

- ^ PMID 37858906.

- ISBN 9781462545452.

- PMID 7699712.

- ^ "Extraction of LSA (Method #1)". Erowid. Archived from the original on September 26, 2014. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- .

- PMID 18956869.

- PMID 35132076.

- PMID 13497365.

- PMID 12707059.

- PMID 30726251.

- ^ a b Hidalgo E (2009). "LSD Samples Analysis". Erowid. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7879-4379-0.

- ^ Fire & Earth Erowid (November 2003). "LSD Analysis – Do we know what's in street acid?". Erowid. Archived from the original on January 26, 2010. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- PMID 9788528.

- ^ S2CID 144527673.

- ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 12th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2020, pp. 1197–1199.

- PMID 28197931.

- ^ S2CID 256574276.

- ^ ISBN 0-07-029325-2. Archivedfrom the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved April 19, 2010 – via The Psychedelic Library.

- ^ Hofmann A (Summer 1969). "LSD Ganz Persönlich" [LSD: Completely Personal]. MAPS (in German). 6 (69). Translated by Ott J. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-19-028296-7. Archivedfrom the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Nichols D (May 24, 2003). "Hypothesis on Albert Hofmann's Famous 1943 "Bicycle Day"". Hofmann Foundation. Archived from the original on September 22, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ Hofmann A. "History Of LSD". Archived from the original on September 4, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ a b c "LSD: The Drug". LSD in the United States (Report). U.S. Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration. October 1995. Archived from the original on April 27, 1999. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ "The CIA's Secret Quest For Mind Control: Torture, LSD And A 'Poisoner In Chief'". NPR.org. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ^ Brecher EM, et al. (Editors of Consumer Reports Magazine) (1972). "How LSD was popularized". Druglibrary.org. Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- The Huffington Post. Archived from the originalon July 14, 2011.

- ^ "Out-Of-Sight! SMiLE Timeline". Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ISBN 0-226-85458-2.

- ^ United States Congress (October 24, 1968). "Staggers-Dodd Bill, Public Law 90-639" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 9, 2010. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ Gasser P (1994). "Psycholytic Therapy with MDMA and LSD in Switzerland". Archived from the original on October 11, 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ Feuer W (November 4, 2020). "Oregon becomes first state to legalize magic mushrooms as more states ease drug laws in 'psychedelic renaissance'". CNBC. Archived from the original on November 4, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ISBN 0-634-05548-8.

- ^ Gilliland J (1969). "Show 41 – The Acid Test: Psychedelics and a sub-culture emerge in San Francisco. [Part 1] : UNT Digital Library" (audio). Pop Chronicles. Digital.library.unt.edu. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- ISBN 0-252-06915-3.

- ISBN 978-1-84755-909-8.

- ^ Taylor M (March 22, 1996). "OBITUARY — Ron Thelin". SFGate. Archived from the original on August 28, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- S2CID 142795620.

- ISBN 9780872865358.

- ^ ISBN 9780306822551.

- ^ Gilmore M (August 25, 2016). "Beatles' Acid Test: How LSD Opened the Door to 'Revolver'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-8147-7552-3.

- ISBN 0-7935-4042-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-312-25464-3.

- ^ Thompson T (June 16, 1967). "The New Far-Out Beatles". Life. Chicago: Time Inc. p. 101. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ISBN 1593730527.

- ^ Daisy Jones (June 5, 2017). "Why Certain Drugs Make Specific Genres Sound So Good". Vice.

- ^ Kendall Deflin (June 22, 2017). "Phishin' With Matisyahu: How LSD "Turned My Entire World Inside Out"".

- ^ "How LSD influenced Western culture". www.bbc.com. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Final act of the United Nations Conference" (PDF). UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances. 1971. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 15, 2012.

- ^ "Poisons Standard". Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian Government Department of Health. July 2016. Archived from the original on March 2, 2017.

- ^ "Misuse of Drugs Act 1981" (PDF). Government of Western Australia. November 18, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2015.

- ^ "Drugs and the law: Report of the inquiry into the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971". Runciman Report. London: Police Foundation. 2000. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016.

- ^ "After the War on Drugs: Blueprint for Regulation". Transform Drug Policy Foundation. 2009. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013.

- ^ Neal v. United States, 516 U.S. 284 (1996)., originating from U.S. v. Neal, 46 F.3d 1405 (7th Cir. 1995)

- ^ Jaeger K (June 29, 2021). "California Lawmakers Approve Bill To Legalize Psychedelics Possession In Committee". Marijuana Moment. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ "Ley de Narcomenudeo". El Pensador (in Spanish). October 17, 2009. Archived from the original on November 30, 2010.

- ^ Explanatory Report to Act No. 112/1998 Coll., which amends the Act No. 140/1961 Coll., the Criminal Code, and the Act No. 200/1990 Coll., on misdemeanors (Report) (in Czech). Prague: Parliament of the Czech Republic. 1998.

- ^ Supreme Court of the Czech Republic (February 25, 2012), 6 Tdo 156/2010 [NS 7078/2010]

- ^ a b DEA (2007). "LSD Manufacture – Illegal LSD Production". LSD in the United States. U.S. Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration. Archived from the original on August 29, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ ISBN 978-0-914171-51-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-433951-4. Archivedfrom the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ "Street Terms: Drugs and the Drug Trade". Office of National Drug Control Policy. April 5, 2005. Archived from the original on April 18, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ^ DEA (2008). "Photo Library (page 2)". US Drug Enforcement Administration. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

- ^ MacLean JR, Macdonald DC, Ogden F, Wilby E (1967). "LSD-25 and mescaline as therapeutic adjuvants.". In Abramson H (ed.). The Use of LSD in Psychotherapy and Alcoholism. New York: Bobbs-Merrill. pp. 407–426.

- ^ Ditman KS, Bailey JJ. "Evaluating LSD as a psychotherapeutic agent". In Hoffer A (ed.). A program for the treatment of alcoholism: LSD, malvaria, and nicotinic acid. pp. 353–402.

- ISBN 9780312551834.

- ^ United States Drug Enforcement Administration (October 2005). "LSD Blotter Acid Mimic Containing 4-Bromo-2,5-dimethoxy-amphetamine (DOB) Seized Near Burns, Oregon" (PDF). Microgram Bulletin. 38 (10). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ United States Drug Enforcement Administration (November 2006). "Intelligence Alert – Blotter Acid Mimics (Containing 4-Bromo-2,5-Dimethoxy-Amphetamine (DOB)) in Concord, California" (PDF). Microgram Bulletin. 39 (11): 136. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ United States Drug Enforcement Administration (March 2008). "Unusual "Rice Krispie Treat"-Like Balls Containing Psilocybe Mushroom Parts in Warren County, Missouri" (PDF). Microgram Bulletin. 41 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ Iversen L (May 29, 2013). "Temporary Class Drug Order Report on 5-6APB and NBOMe compounds" (PDF). Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Gov.Uk. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ United States Drug Enforcement Administration (March 2009). ""Spice" – Plant Material(s) Laced With Synthetic Cannabinoids or Cannabinoid Mimicking Compounds". Microgram Bulletin. 42 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 18, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ United States Drug Enforcement Administration (November 2005). "Bulk Marijuana in Hazardous Packaging in Chicago, Illinois" (PDF). Microgram Bulletin. 38 (11). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ United States Drug Enforcement Administration (December 2007). "SMALL HEROIN DISKS NEAR GREENSBORO, GEORGIA" (PDF). Microgram Bulletin. 40 (12). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ Erowid. "25I-NBOMe (2C-I-NBOMe) Fatalities / Deaths". Erowid. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ Hastings D (May 6, 2013). "New drug N-bomb hits the street, terrifying parents, troubling cops". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ^ Feehan C (January 21, 2016). "Powerful N-Bomb drug – responsible for spate of deaths internationally – responsible for hospitalisation of six in Cork". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ Iversen L (May 29, 2013). "Temporary Class Drug Order Report on 5-6APB and NBOMe compounds" (PDF). Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Gov.Uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ Dyck E (1965). "Flashback: Psychiatric Experimentation with LSD in Historical Perspective". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 50 (7).

- ^ "The Albert Hofmann Foundation". Hofmann Foundation. Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ a b c "LSD-Assisted Psychotherapy". MAPS. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- PMID 23627783.

- ^ "LSD Therapy for Persons Suffering From Major Depression - Full Text View". ClinicalTrials.gov. February 8, 2021. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- S2CID 233243518.

- PMID 32038315.

- PMID 36123427.

- PMID 35060714.

- ^ Cohen, S. (1959). "The therapeutic potential of LSD-25". A Pharmacologic Approach to the Study of the Mind, p. 251–258.

- PMID 13810249. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2012. Via "Abstract". Hofmann.org. Archivedfrom the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- S2CID 16588263.

- PMID 25083275.

- PMID 28447622.

- ^ Carhart-Harris R (April 20, 2021). "Psychedelics are transforming the way we understand depression and its treatment". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- S2CID 1908638.

- from the original on October 3, 2009.

- ^ Stafford PG, Golightly BH (1967). LSD, the problem-solving psychedelic. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012.

- ^ "Scientific Problem Solving with Psychedelics – James Fadiman". YouTube. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- OCLC 1031461623.

- ^ "Psychiater Gasser bricht sein Schweigen". Basler Zeitung. July 28, 2009. Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- PMID 29898390.

- ^ Dolan EW (August 11, 2022). "Neuroscience research suggests LSD might enhance learning and memory by promoting brain plasticity". Psypost - Psychology News. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2020.

- ^ "Famous LSD users". The Good Drugs Guide. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ "People on psychedelics". Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- ^ Mason D (Autumn 2015). "Review: Awe for Auden". The Hudson Review. 68 (3). The Hudson Review, Inc.: 492–500.

- ^ Auden WH (November 15, 1971). "W. H. Auden at Swathmore; An hour of questions and answers with Auden". Exhibition notes from the W.H. Auden Collection. the Swarthmore College Library. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ MacMonagle N (February 17, 2007). "A Master of Memorable speech". The Irish Times.

- ^ Meyer A (January 24, 2022). "Daniel Ellsberg Talks Psychedelics, Consciousness and World Peace". Lucid News. Archived from the original on January 29, 2022. Retrieved January 29, 2022.

- OCLC 10925248.

- OCLC 243743850.

- ^ Alderson J (April 20, 2010). "Q&A with Jerry Garcia: Portrait of an Artist as a Tripper". Relix Magazine. Archived from the original on May 21, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ^ "The Bill Gates Interview". Playboy. July 1994. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014.

- ^ Colman D (October 2011). "Aldous Huxley's LSD Death Trip". Open Culture. Archived from the original on November 12, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ Bosker B (October 21, 2011). "The Steve Jobs Reading List: The Books And Artists That Made The Man". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on October 22, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ "LSD, My Problem Child · Radiance from Ernst Junger". www.psychedelic-library.org. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Is 'Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds' Code for LSD?". Snopes.com. February 15, 1998. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ^ Matus V (June 2004). "The Truth Behind "LSD"". The Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ "When Michel Foucault Tripped on Acid in Death Valley and Called It "The Greatest Experience of My Life"". Open Culture. September 1975. Archived from the original on March 15, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ Penner J (June 17, 2019). "Blowing The Philosopher's Fuses: Michel Foucault's LSD Trip in The Valley of Death". Los Angeles Review of Books. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021. Wade: "We fell silent to listen to Stockhausen's Songs of Youth. Zabriskie Point was filled with the sound of a kindergarten playground overlaid with electric tonalities. Kontakte followed. Glissandos bounced off the stars, which glowed like incandescent pinballs. Foucault turned to Michael and said this is the first time he really understood what Stockhausen had achieved".

- ISBN 9781597144636. In a letter to Wade, dated 16 September 1978, Foucault authorised the book's publication and added: "How could I not love you?"

- ^ Harrison A (January 16, 2006). "LSD: The Geek's Wonder Drug?". Wired. Archived from the original on May 5, 2008. Retrieved March 11, 2008.

Like Herbert, many scientists and engineers also report heightened states of creativity while using LSD. During a press conference on Friday, Hofmann revealed that he was told by Nobel-prize-winning chemist Kary Mullis that LSD had helped him develop the polymerase chain reaction that helps amplify specific DNA sequences.

- ^ Higgins C (April 14, 2018). "'There is no such thing as past or future': physicist Carlo Rovelli on changing how we think about time". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-307-94743-7. Archivedfrom the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

On the West Coast in the early 1960s LSD and morning glory seeds were readily available, so I sampled those, too.

- ^ Bose SD (December 27, 2021). "When Trey Parker and Matt Stone went to the Oscars on LSD Swapnil Dhruv Bose". FarOutMagazine.co.uk. Archived from the original on January 20, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

Further reading

- Bebergal P (June 2, 2008). "Will Harvard drop acid again? Psychedelic research returns to Crimsonland". The Phoenix. Boston. Archived from the original on September 20, 2008.

- Passie T, Halpern JH, Stichtenoth DO, Emrich HM, Hintzen A (2008). "The pharmacology of lysergic acid diethylamide: a review". CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 14 (4): 295–314. PMID 19040555.

- Winstock AR, Timmerman C, Davies E, Maier LJ, Zhuparris A, Ferris JA, et al. (2021). Global Drug Survey (GDS) 2020 Psychedelics Key Findings Report (PDF) (Report).

External links

- Drug Profiles: LSD European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction

- LSD-25 at Erowid

- LSD at PsychonautWiki

- LSD entry in TiHKAL • info Archived August 28, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal – Lysergic acid diethylamide

Documentaries

- Hofmann's Potion a documentary on the origins of LSD, 2002

- Power & Control LSD in The Sixties on YouTube, documentary film directed by Aron Ranen, 2006

- Inside LSD National Geographic Channel, 2009

- How to Change Your Mind Netflix docuseries, 2022