Machimoi

The term máchimoi (

History

Herodotus and the Late Period

The earliest attestation of this term given to

As well as Herodotus, also other Greek authors such as

Ptolemaic Period

Máchimoi were still present during the Ptolemaic period, and most scholars considers them as the direct successors of their Late Period counterparts; Ptolemaic máchimoi are mostly still seen as a caste of native-Egyptian, land-granted, low-ranked warriors whom, with the passing of time, takes on increasingly important roles alongside the Greek army likely since the

Curiously, under the Ptolemies the name máchimoi is attested only on documents while during the Late Period they were mentioned exclusively on Greek literary works: for example, Diodorus clearly calls máchimoi the Egyptian soldiers of pharaoh Teos, but not their Ptolemaic counterparts.[7]

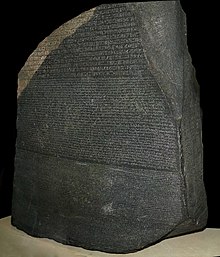

The earliest mention of máchimoi on Ptolemaic documents is dating back to the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (261 BCE) and refers to guard duties; this was not uncommon, as from many documents it seems that they sometimes were guards and sometimes had purely army duties.[8] However, the most famous document mentioning them is the Rosetta Stone (Greek text, row 19) made under Ptolemy V Epiphanes (196 BCE), which refers to an amnesty for some deserted máchimoi.[9]

2013 reinterpretation

A 2013 paper by historian Christelle Fischer-Bovet revised many of the traditional claims about the máchimoi. She challenged most of Herodotus' description, pointing out that ancient Egyptians never used similar caste systems, and both the total numbers of máchimoi and of the lands given to them are almost certainly unsustainable, suggesting that Herodotus unintentionally merged professional military officers with a militia composed by commoners who were called to arms if necessary, and attributed to the whole group an elite status not much different from that of Greek Spartiates.[10] Fischer-Bovet also perceived a discontinuity between Late Period and Ptolemaic máchimoi and criticized the aforementioned traditional rendering of the latter group; historical documents mentioning Greek máchimoi during the Ptolemaic Period proves that they were not exclusively native Egyptians as usually thought, suggesting that the term was rather an indicator of their military role (for example, the pike-bearing máchimoi epilektoi or the mounted máchimoi hippeis) and/or of the amount of land received (a pentarouros, for example, was a máchimos granted with five arourai of land) and not of their ethnicity.[7] In this regard, she accepts the idea that the máchimoi were the lowest level of the military hierarchy, but their socio-economic status was still higher than that of the average peasant.[11]

References

- ^ Based on figures 95 and 96 respectively of: Sekunda, Nicholas Viktor (1995). Seleucid and Ptolemaic Reformed Armies 168-145 BC, Volume 2: The Ptolemaic Army. Montvert Publications.

- ^ Fischer-Bovet 2013, pp. 210–12

- ^ Fischer-Bovet 2013, p. 210

- ISBN 0 521 23348 8, p. 342

- ISBN 3-515-08740-0, pp. 61–84

- ^ Fischer-Bovet 2013, p. 220 n. 67

- ^ a b Fischer-Bovet 2013, pp. 219–21

- ^ Fischer-Bovet 2013, p. 222

- ^ Fischer-Bovet 2013, pp. 223–24

- ^ Fischer-Bovet 2013, pp. 210–12; 216–17

- ^ Fischer-Bovet 2013, p. 225

Sources

- Christelle Fischer-Bovet (2013), "Egyptian warriors: the Machimoi of Herodotus and the Ptolemaic Army". The Classical Quarterly 63 (01), pp. 209–36, .

- ISBN 3-406-47154-4, pp. 20–31; 47–53.