Macrauchenia

| Macrauchenia Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype skeleton of M. patachonica (larger) and Phenacodus primaevus (smaller) at American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | †Litopterna |

| Family: | †Macraucheniidae |

| Subfamily: | †Macraucheniinae |

| Genus: | †Macrauchenia Owen, 1838 |

| Type species | |

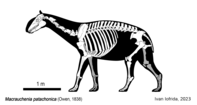

| †Macrauchenia patachonica Owen, 1838

| |

| |

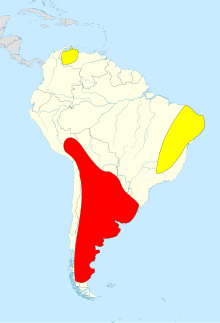

| Map showing the distribution of Macrauchenia in red, and Xenorhinotherium in yellow, inferred from fossil finds | |

Macrauchenia ("long llama", based on the now-invalid llama genus, Auchenia, from Greek "big neck") is an extinct genus of large ungulate native to South America from the late Pliocene to the end of the Pleistocene.[1] It is a member of the extinct order Litopterna, a group of South American native ungulates distinct from the two orders which contain all living ungulates which had been present in South America since the early Cenozoic, over 60 million years ago, prior to the arrival of living ungulates in South America around 2.5 million years ago as part of the Great American Interchange.[2] The bodyform of Macrauchenia has been described as similar to a camel,[3] being one of the largest known litopterns, with an estimated body mass of around 1 tonne.[2] The genus gives its name to its family, Macraucheniidae, which like Macrauchenia typically had long necks and three toed feet, as well a retracted nasal region,[1] which in Macrauchenia manifests as the nasal opening being on the top of the skull behind the eye sockets.[4] This has historically been argued to correspond to the presence of a tapir-like proboscis, but some recent authors suggest a moose-like prehensile lip is more likely.[5]

Only one species is generally considered valid,[6] M. patachonica, which was described by Richard Owen based on remains discovered by Charles Darwin during the voyage of the Beagle.[7] M. patachonica is primarily known from localities in the Pampas, but is known from remains found across the Southern Cone extending as far south as southernmost Patagonia, and as far northeast as Southern Peru. Another genus of macraucheniid Xenorhinotherium was present in northeast Brazil and Venezuela during the Late Pleistocene.[4]

Macrauchenia became extinct as part of the end-Pleistocene extinctions around 12,000 years ago, along with the vast majority of other large mammals native to the Americas.[2]

Taxonomy

Macrauchenia fossils were first collected on 9 February 1834 at Port St Julian in Patagonia (Argentina) by Charles Darwin, when HMS Beagle was surveying the port.[8] As a non-expert he tentatively identified the leg bones and fragments of spine he found as "some large animal, I fancy a Mastodon". In 1837, soon after the Beagle's return, the anatomist Richard Owen identified the bones, including vertebrae from the back and neck, as from a gigantic creature resembling a llama or camel, which Owen named Macrauchenia patachonica.[9] In naming it, Owen noted the original Greek terms µακρος (makros, large or long), and αυχην (auchèn, neck) as used by Illiger as the basis of Auchenia as a generic name for the llama, Vicugna and so on.[10] The find was one of the discoveries leading to the inception of Darwin's theory. Since then, more Macrauchenia fossils have been found, mainly in Patagonia, but also in Bolivia, Chile and Venezuela.

The related genus Cramauchenia was named by Florentino Ameghino as a deliberate anagram of Macrauchenia.

Evolution

It is likely that Macrauchenia evolved from earlier litopterns

Sequencing of mitochondrial DNA extracted from an M. patachonica fossil from a cave in southern Chile indicates that Macrauchenia (and by inference, Litopterna) is the sister group to Perissodactyla, with an estimated divergence date of sixty-six million years ago.[14][15] Analysis of collagen sequences obtained from Macrauchenia and Toxodon reached a similar conclusion and extended membership in the sister group clade to notoungulates.[16][17]

Description

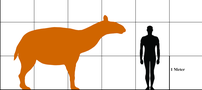

Macrauchenia had a somewhat camel-like body, with sturdy legs, a long neck and a relatively small head. Its feet, however, more closely resembled those of a modern rhinoceros, with one central toe and two side toes on each foot. It was a large animal, with a body length of around 3 metres (9.8 ft) and a weight up to 909–1,042.8 kg (2,004–2,299 lb), about the size of a black rhinoceros.[18][19][20]

One striking characteristic of Macrauchenia is the openings for the nostrils on top of the head, above and between the eyes. Increasingly retracted nostrils are an evolutionary trend in later litopterns. Because mammals with trunks show the nostrils in a similar position, a popular hypothesis is that Macrauchenia had a trunk similar to a

The snout of Macrauchenia is completely enclosed by bone, and the animal has an elongated neck that allowed it to reach upward; no living mammal with a proboscis has these features. An alternative hypothesis is that these litopterns were high browsers on tough and thorny vegetation, and retracted nostrils allowed them to reach leaves without being impaled in the nose. Sauropod dinosaurs (reconstructed as high browsers on conifer needles and cycads) have similar snouts, and living giraffes and gerenuks, high browsers on thorny vegetation, have more retracted nostrils than related taxa with other feeding habits.[12]

One insight into Macrauchenia's habits is that its ankle joints and shin bones may indicate that it was adapted to have unusually good mobility, being able to rapidly change direction when it ran at high speed.[24]

Macrauchenia is known, like its relative Theosodon, to have had a full set of 44 teeth.[citation needed]

Paleobiology

Macrauchenia was a herbivore, likely living on leaves from trees or grasses. Carbon isotope analysis of M. patachonica's

The genus was widespread, found in environments that ranged from dry to humid, from southern Chile to northeastern Brazil and the coast of Venezuela. Fossils of M. ullomensis have been found in Bolivia at altitudes up to 4000 meters. Habits and diet may have varied depending on the environment, but in plant feeders an elongated neck is usually an adaptation to allow high browsing on trees and shrubs. As the genus was not confined to forest, it was probably able to exploit more marginal environments by mixing high browsing with low browsing and grazing. A site in northern Chile preserved the remains of five subadults associated together, which suggests Macrauchenia may have lived in large herds or family groups.[12]

When Macrauchenia first arose, it could have been preyed upon by the largest of native South American mammal predators, the sabertoothed

It is presumed that Macrauchenia dealt with its predators primarily by outrunning them, or, failing that, kicking them with its long, powerful legs. The large size of adults would have limited their vulnerability to most predators. Its potential ability to twist and turn at high speed could have enabled it to evade pursuers; both Thylacosmilus and S. populator were ambush hunters likely unable to run down prey over distance if the prey evaded the first attack.

Distribution

Fossils of Macrauchenia have been found in:[27]

- Miocene

- Epecuén Formation, Argentina

- Pliocene

- Pleistocene

References

- ^ ISSN 1064-7554.

- ^ S2CID 213737574.

- S2CID 91879648, retrieved 2024-01-30

- ^ S2CID 213795563.

- .

- ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ Fernicola, J. C., Vizcaino, S. F., & De Iuliis, G. (2009). The fossil mammals collected by Charles Darwin in South America during his travels on board the HMS Beagle. Revista De La Asociación Geológica Argentina, 64(1), 147-159. Retrieved from https://revista.geologica.org.ar/raga/article/view/1339

- ISBN 9780521003179. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

- ^ "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 238 — Darwin, C. R. to Henslow, J. S., Mar 1834". Archived from the original on 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ^ Owen 1838, p. 35

- ^ "Tectonic history: into the deep freeze". Discovering Antarctica. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- ^ a b c Croft, Darin (2016). Horned Armadillos and Rafting Monkeys; the Fascinating Fossil Mammals of South America. Indiana University Press.

- PMID 28654082.

- ^ Strickland, A. (June 27, 2017). "DNA solves ancient animal riddle that Darwin couldn't". CNN. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- S2CID 4467386.

- PMID 25833851.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84028-152-1.

- PMID 24676170.

- ^ http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/16838?show=full (in Spanish)

- ISSN 0044-5231.

- S2CID 219014558.

- ^ "12,000-Year-Old Rock Drawings of Ice Age Megafauna Discovered in Colombian Amazon | Archaeology | Sci-News.com". Breaking Science News | Sci-News.com. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ^ Fariña, Richard A.; Blanco, R. Ernesto; Christiansen, Per (2005). "Swerving as the escape strategy of Macrauchenia patachonica Owen (Mammalia; Litopterna)". Ameghiniana. 42 (4): 752–760.

- S2CID 88948874.

- ^ Anton, Mauricio. "Sabertooth". Indiana University Press. Archived from the original on 2015-06-05. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- ^ Macrauchenia at Fossilworks.org

Further reading

- Cox, Barry; Harrison, Colin; Savage, R.J.G.; Gardiner, Brian; Palmer, Douglas (1999) [1988]. "South American Hoofed Mammals (Continued)". The Simon & Schuster Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Creatures: A Visual Who's Who of Prehistoric Life. ISBN 0-684-86411-8.

- Owen, Richard (1838). "Description of Parts of the Skeleton of Macrauchenia patachonica". In Darwin, C. R. (ed.). Fossil Mammalia Part 1 No. 1. The zoology of the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle. London: Smith Elder and Co.

- Parsons, Jayne (2001). Dinosaur Encyclopedia. DK.