Madeline Montalban

Madeline Montalban | |

|---|---|

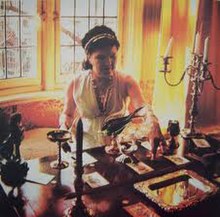

Montalban in the 1970s; this image was published in the magazine Man, Myth and Magic. | |

| Born | Madeline Sylvia Royals 8 January 1910 Blackpool, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 11 January 1982 (aged 72) London, England |

| Occupation(s) | Astrologer; ceremonial magician |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 1 |

Madeline Montalban (born Madeline Sylvia Royals; 8 January 1910 – 11 January 1982) was an English astrologer and ceremonial magician. She co-founded the esoteric organisation known as the Order of the Morning Star (OMS), through which she propagated her own form of Luciferianism.

Born in

In 1952 she met Nicholas Heron, with whom she entered into a relationship. After moving to

Having refused to publish her ideas in books, Montalban became largely forgotten following her death, although the OMS continued under new leadership. Her life and work was mentioned in various occult texts and historical studies of esotericism during subsequent decades; a short biography by Julia Philips was published by the Atlantis Bookshop in 2012.

Biography

Early life: 1910–1938

Madeline Sylvia Royals was born on 8 January 1910 in

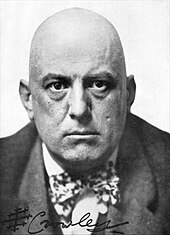

In the early 1930s, she left Blackpool, and moved south to London. Her reasons for doing so have never been satisfactorily explained, and she would offer multiple, contradictory accounts of her reasoning in later life. According to one account, her father sent her to study with the famed occultist and mystic

Although her own accounts of the initial meeting are unreliable, Montalban met with Crowley, embracing the city's occult scene.

Marriage and London Life: 1939–1951

By the end of the 1930s, Montalban was living on Grays Inn Road in the

She continued her publication of articles under an array of pseudonyms in London Life, and from February 1947 was responsible for a regular astrological column entitled "You and Your Stars" under the name of Nina del Luna.[15] She also undertook other work, and in the late 1940s, Michael Houghton, proprietor of Bloomsbury's esoteric-themed Atlantis Bookshop, asked her to edit a manuscript of Gardner's novel High Magic's Aid, which was set in the Late Middle Ages and which featured practitioners of a Witch-Cult; Gardner later alleged that the book contained allusions to the ritual practices of the New Forest coven of Pagan Witches who had initiated him into their ranks in 1939.[16] Gardner incorrectly believed that Montalban "claimed to be a Witch; but got evrything [sic] wrong" although he credited her with having "a lively imagination."[17] Although initially seeming favourable to Gardner, by the mid-1960s she had become hostile towards him and his Gardnerian tradition, considering him to be "a 'dirty old man' and sexual pervert."[18] She also expressed hostility to another prominent Pagan Witch of the period, Charles Cardell, although in the 1960s became friends with the two Witches at the forefront of the Alexandrian Wiccan tradition, Alex Sanders and his wife, Maxine Sanders, who adopted some of her Luciferian angelic practices.[19] She personally despised being referred to as a "witch", and was particularly angry when the esoteric magazine Man, Myth and Magic referred to her as "The Witch of St. Giles", an area of Central London which she would later inhabit.[20]

In his 1977 book Nightside of Eden, the Thelemite Kenneth Grant, then leader of the Typhonian OTO, told a story in which he claimed that both he and Gardner performed rituals in the St. Giles flat of a "Mrs. South", probably a reference to Montalban, who often used the pseudonym of "Mrs North". The truthfulness of Grant's claims have been scrutinised by both Doreen Valiente and Julia Philips, who have pointed out multiple incorrect assertions with his account.[21]

Prediction and The Order of the Morning Star: 1952–1964

From August 1953, Montalban ceased working for London Life, publishing her work in the magazine Prediction, one of the country's best-selling esoteric-themed publications. Starting with a series on the uses of the tarot, in May 1960 she was employed to produce a regular astrological column for Prediction.[22] Supplementing such esoteric endeavours, she penned a series of romantic short stories for publication in magazines.[23] Throughout the 1950s she released a series of booklets under different pseudonyms that were devoted to astrology; in one case, she published the same booklet under two separate titles and names, as Madeline Montalban's Your Stars and Love and Madeline Alvarez's Love and the Stars. She never wrote any books, instead preferring the shorter booklets and articles as mediums through which to propagate her views, and was critical of those books that taught the reader how to perform their own horoscopes, believing that they put professional astrologers out of business.[24]

In 1952 she met Nicholas Heron, with whom she entered into a relationship. An engraver, photographer and former journalist for the

She encouraged members of her OMS course to come and meet with her, and developed friendships with a number of them, blurring the distinction between teacher and pupil.

Later life: 1964–1982

From 1964 until 1966 she dwelt in a flat at 8 Holly Hill, Hampstead, which was owned by the husband of one of her OMS students, the Latvian exile and poet Velta Snikere.[10] After leaving Holly Hill, Montalban moved to a flat in the Queen Alexandra Mansions at 3 Grape Street in the St. Giles district of Holborn. Here, she was in close proximity to the two primary bookstores then catering to occult interests, Atlantis Bookshop and Watkins Bookshop, as well as to the British Museum.[35] She offered one of the rooms in her flat to a young astrologer and musician, Rick Hayward, whom she had met in the summer of 1967; he joined the OMS, and in the last few months of Montalban's life authored her astrological forecasts for Prediction. After her death, he continued publishing astrological prophecies in Prediction and Prediction Annual until summer 2012.[36]

In 1967, Michael Howard, a young man interested in witchcraft and the occult wrote to Montalban after reading one of her articles in Prediction; she invited him to visit her at her home. The two became friends, with Montalban believing that she could see the "Mark of Cain" in his aura.[37] She invited him to become a student of the ONS, which he duly did.[38] Over the coming year, he spent much of his time with her, and in 1968 they went on what she called a "magical mystery tour" to the West Country, visiting Stonehenge, Boscastle and Tintagel.[39] In 1969, he was initiated into Gardnerian Wicca, something she disapproved of, and their friendship subsequently "hit a stormy period" with the pair going "[their] own ways for several years."[40]

A lifelong smoker, Montalban developed lung cancer, causing her death on 11 January 1982.[41] The role of sorting out her financial affairs fell to her friend, Pat Arthy, who discovered that despite her emphasis on the magical attainment of material wealth, she owned no property and that her estate was worth less than £10,000.[42] The copyright of her writings fell to her daughter, Rosanna, who entrusted the running of the OMS to two of Montalban's initiates, married couple Jo Sheridan and Alfred Douglas, who were authorised as the exclusive publishers of her correspondence course.[31] Sheridan – whose real name was Patricia Douglas – opened an alternative therapy centre in Islington, North London, in the 1980s, before retiring to Rye, East Sussex in 2002, where she continued running the OMS correspondence course until her death in 2011.[43]

Personal life and magico-religious beliefs

According to her biographer Julia Philips, Montalban had been described by her magical students as "tempestuous, generous, humorous, demanding, kind, capricious, talented, volatile, selfish, goodhearted, [and] dramatic".[44] Philips noted that she was a woman who made a "definite impression" in all those whom she encountered, but who equally could be quite shy and disliked being interviewed in anything other than print.[44] Philips asserted that Montalban had a "mercurial personality" and could be kind and generous at one moment and fly into a violent temper the next.[45] Several of her friends noted that she was prudish when it came to sexual matters,[46] and her friend Maxine Sanders stated that even as an elderly lady Montalban boasted of only taking men under the age of twenty-five as her lovers.[47] She would take great pleasure in causing arguments, particularly between a couple who were romantically involved.[48]

Describing herself as a "

Legacy

In 2012, Neptune Press – the publishing arm of Bloomsbury's Atlantis Bookshop – released the biography Madeline Montalban: The Magus of St Giles, written by Anglo-Australian Wiccan Julia Philips. Philips noted that for much of the project she found it difficult separating fact from fiction when it came to Montalban's life, but that she had been able to nevertheless put together a biographical account, albeit incomplete, of "one of the truly great characters of English occultism."[56]

References

Footnotes

- ^ Heselton 2000, p. 300; Philips 2012, p. 21.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Howard 2010, p. 6.

- ^ Douglas & Sheridan 2007; Philips 2012, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Philips 2012, p. 35.

- ^ Heselton 2000, p. 300; Philips 2012, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Philips 2012, p. 27.

- ^ Hutton 1999, p. 239.

- ^ Valiente 1989, pp. 49–50; Heselton 2000, p. 301; Philips 2012, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Philips 2012, p. 65.

- ^ Valiente 1989, p. 49; Hutton 1999, pp. 224, 244; Heselton 2000, p. 300; Heselton 2003, pp. 245–246, 377.

- ^ Heselton 2003, p. 246.

- ^ Howard 2010, p. 7; Philips 2012, p. 69.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Philips 2012, p. 70.

- ^ Grant 1977, pp. 123–124; Valiente 1989, p. 50; Philips 2012, pp. 33–35.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 64–66.

- ^ Philips 2012, p. 66.

- ^ Philips 2012, p. 63.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Philips 2012, p. 81.

- ^ Douglas & Sheridan 2007; Philips 2012, p. 20.

- ^ Philips 2012, p. 89.

- ^ Douglas & Sheridan 2007; Philips 2012, p. 89.

- ^ a b Douglas & Sheridan 2007.

- ^ Philips 2012, p. 85.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Philips 2012, p. 83.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 36, 39.

- ^ Douglas 2013, p. 32.

- ^ Howard 2010, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Howard 2010, p. 6; Gregorius 2013, p. 243.

- ^ Howard 2010, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Howard 2010, p. 8.

- ^ Douglas & Sheridan 2007; Philips 2012, p. 99.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 88, 99.

- ^ Howard 2012, p. 44.

- ^ a b Philips 2012, p. 7.

- ^ Philips 2012, p. 11.

- ^ Philips 2012, p. 34.

- ^ Sanders 2008, p. 239.

- ^ Philips 2012, p. 37.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 26, 85–86.

- ^ Philips 2012, p. 86.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Howard 2010, p. 7; Philips 2012, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Hutton 1999, p. 268.

- ^ Howard 2004.

- ^ Gregorius 2013, p. 244.

- ^ Philips 2012, pp. 7–8.

Bibliography

- Douglas, Alfred; Sheridan, Jo (2007). "Madeline Montalban and the Order of the Morning Star". SheridanDouglas.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- Douglas, Alfred (February 2013). "Rick Hayward (1947–2012)". The Cauldron. 147: 32. ISSN 0964-5594.

- ISBN 978-0-584-10206-2.

- Gregorius, Fredrik (2013). "Luciferian Witchcraft: At the Crossroads between Paganism and Satanism". In Per Faxneld and Jesper Aa. Petersen (ed.). The Devil's Party: Satanism in Modernity. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 229–249. ISBN 978-0-19-977924-6.

- ISBN 978-1-86163-110-7.

- Heselton, Philip (2003). Gerald Gardner and the Cauldron of Inspiration: An Investigation into the Sources of Gardnerian Witchcraft. Milverton, Somerset: Capall Bann. ISBN 978-1-86163-164-0.

- Howard, Michael (2004). The Book of Fallen Angels. Milverton, Somerset: Capall Bann. ISBN 978-1-86163-236-4.

- Howard, Michael (February 2010). "A Seeker's Journey". The Cauldron. 135: 3–11. ISSN 0964-5594.

- Howard, Michael (May 2012). "Patricia 'Patsy' Douglas (1919–2011)". The Cauldron. 144: 44. ISSN 0964-5594.

- ISBN 978-0-19-162241-0.

- Philips, Julia (2012). Madeline Montalban: The Magus of St. Giles. Bloomsbury, London: Neptune Press. ISBN 978-0-9547063-9-5.

- Sanders, Maxine (2008). Firechild: The Life and Magic of Maxine Sanders 'Witch Queen'. Oxford: Mandrake of Oxford. ISBN 978-1-869928-97-1.

- ISBN 978-0-7090-3715-6.