Maliki school

| Part of a series on Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

|

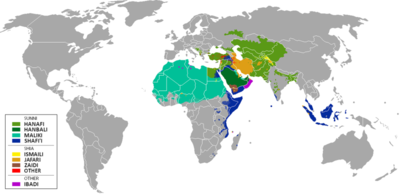

The Maliki school or Malikism (

The Maliki school is one of the largest groups of Sunni Muslims, comparable to the

In the

One who ascribes to the Maliki school is called a Maliki, Malikite or Malikist (

History

Although Malik ibn Anas was himself a native of Medina, his school faced fierce competition for followers in the Muslim east, with the

Imam Malik (who was a teacher of Imam

The Malikis enjoyed considerably more success in Africa, and for a while in Spain and Sicily. Under the

Although

Although initially hostile to some mystical practices, Malikis eventually learned to coexist with Sufi customs as the latter became widespread throughout North and West Africa. Many Muslims now adhere to both Maliki law and a Sufi order.[17]

Principles

| Part of a series on Aqidah |

|---|

|

|

Including:

|

The Maliki school's sources for

The Mālikī school primarily derives from the work of Malik ibn Anas, particularly the Muwatta Imam Malik, also known as Al-Muwatta. The Muwaṭṭa relies on Sahih Hadiths, includes Malik ibn Anas' commentary, but it is so complete that it is considered in Maliki school to be a sound hadith in itself.[2] Mālik included the practices of the people of Medina and where the practices are in compliance with or in variance with the hadiths reported. This is because Mālik regarded the practices of Medina (the first three generations) to be a superior proof of the "living" sunnah than isolated, although sound, hadiths. Mālik was particularly scrupulous about authenticating his sources when he did appeal to them, as well as his comparatively small collection of aḥādith, known as al-Muwaṭṭah (or, The Straight Path).[2] The example of Maliki approach in using the opinion of Sahabah were recorded in Muwatta Imam Malik per ruling of cases regarding the law of consuming Gazelle meat.[18] This tradition were used from opinion of Zubayr ibn al-Awwam.[18] Malik also included the daily practice of az-Zubayr as his source of "living sunnah" (living tradition) for his guideline to pass verdicts for various matters, in accordance of his school of though method.[19]

The second source, the Al-Mudawwana, is the collaborator work of Mālik's longtime student,

The Maliki school is most closely related to the

Notable differences from other schools

The Maliki school differs from the other Sunni schools of law most notably in the sources it uses for derivation of rulings. Like all Sunni schools of Sharia, the Maliki school uses the

Malik bin Anas himself also accepted

Notable Mālikīs

- Ibn Abd al-Hakam (d. 829), one of the Egyptian scholars who developed the Maliki school in Egypt [24]

- Asbagh ibn al-Faraj (d. 840), Egyptian scholar [25]

- Yahya al-Laithi (d. 848), Andalusian scholar, introduced the Maliki school in Al-Andalus

- Sahnun (AH 160/776–77 – AH 240/854–55), Sunnī jurist and author of the Mudawwanah, one of the most important works in Mālikī law

- Ibn Abi Zayd(310/922–386/996), Tunisian Sunnī jurist and author of the Risālah, a standard work in Mālikī law

- Yusuf ibn abd al-Barr(978–1071), Andalusian scholar

- Ibn Tashfin (1061–1106), one of the prominent leaders of the Almoravid dynasty

- Qadi Ayyad(d. 1149), a great Imam and Qadi in Maliki jurisprudence

- Ibn Rushd (Averroes) (1126–1198), philosopher and scholar

- Al-Qurtubi (1214–1273)

- Shihab al-Din al-Qarafi (1228–1285), Moroccan jurist and author who lived in Egypt

- Khalil ibn Ishaq al-Jundi (d. ca. 1365), Egyptian jurist, author of Mukhtasar

- Ibn Battuta (February 24, 1304 – 1377), explorer

- Ibn Khaldūn (1332/AH 732–1406/AH 808), scholar, historian and author of the Muqaddimah

- Abu Ishaq al-Shatibi (d. 1388), a famous Andalusian Maliki jurist

- Sidi Boushaki (d. 1453), a famous Algerian Maliki jurist

- Sidi Abd al-Rahman al-Tha'alibi(d. 1479), a famous Algerian Maliki jurist

Contemporary Malikis

- Usman dan Fodio (1754–1817), founder of the Sokoto Caliphate

- El Hadj Umar Tall (1794–1864), founder of the Toucouleur Empire

- Emir Abdelkader (1808–1883), Algerian sufi and politician, religious and military leader who led a struggle against the French colonial invasion

- Ahmad al-Alawi (1869–1934), Algerian Sufi leader

- Omar Mukhtar(1862–1931), Libyan resistance leader

- Muhammad Ibn 'Abd al-Karim al-Khattabi, Moroccan resistance leader

- Abu-Abdullah Adelabu

- Abdalqadir as-Sufi (1930–2021), Scottish shaykh and founder of the Murabitun World Movement

- Abdullahi Aliyu Sumaila

- Ahmed Saad Al-Azhari, British Islamic scholar and a graduate of Al-Azhar university. Saad was formerly a Shafi’i before adopting the Maliki school

- Muḥammad al Tahir ibn Ashur (1879-1973) Tunisian Islamic Scholar and Shariah Judge

- Abdullahi dan Fodio (1766–1829), Sufi and brother of Usman dan Fodio

See also

- Outline of Islam

- Glossary of Islam

- List of Islamic scholars

- The Seven Fuqaha of Medina

- Malikization of the Maghreb

- Malikism in Algeria

- Adhan

- Islamic views on sin

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7591-0991-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0275987336, pp 160

- ^ a b c d Jurisprudence and Law – Islam Reorienting the Veil, University of North Carolina (2009)

- ISBN 978-0415421256, pp. 16–18

- ISBN 9780756712297.

- ISBN 978-1440857058.

- ISBN 978-0393321654, p. 67

- ^ Wilfrid Scawen Blunt and Riad Nourallah, The future of Islam, Routledge, 2002, page 199

- ^ Ira Marvin Lapidus, A history of Islamic societies, Cambridge University Press, 2002, page 308

- ^ Camilla Adang, This Day I have Perfected Your Religion For You: A Zahiri Conception of Religious Authority, pg. 17. Taken from Speaking for Islam: Religious Authorities in Muslim Societies. Ed. Gudrun Krämer and Sabine Schmidtke. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2006.

- ^ Dutton, Yasin, The Origins of Islamic Law: The Qurʼan, the Muwaṭṭaʼ and Madinan ʻAmal, p. 16

- ^ Haddad, Gibril F. (2007). The Four Imams and Their Schools. London, the U.K.: Muslim Academic Trust. pp. 121–194.

- ^ "Imam Ja'afar as Sadiq". History of Islam. Archived from the original on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ Maribel Fierro, Proto-Malikis, Malikis and Reformed Malikis in al-Andalus, pg. 61. Taken from The Islamic School of Law: Evolution, Devolution and Progress. Eds. Peri Bearman, Rudolph Peters and Frank E. Vogel. Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2005.

- ^ Fierro, "The Introduction of Hadith in al-Andalus (2nd/8th - 3rd/9th centuries)," pg. 68–93. Der Islam, vol. 66, 1989.

- ISBN 9780313344428. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8.

- ^ a b Ibn Anas (2007, p. 368)

- ^ Wheeler (1996, pp. 28–29)

- ISBN 9780521793728– via Google Books.

- ^ ISBN 978-1853332807, pp. 16–17

- ^ Mansoor Moaddel, Islamic Modernism, Nationalism, and Fundamentalism: Episode and Discourse, pg. 32. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- ^ Reuben Levy, Introduction to the Sociology of Islam, pg. 237, 239 and 245. London: Williams and Norgate, 1931–1933.

- ISBN 978-90-04-11628-3.

- S2CID 204381746.

Citation

- Ibn Anas, Malik (2007). Muwatta Imam Malik. Translated by Muphtah Aduli. Dar al-Kotob al-Ilmiyah. ISBN 9782745155719. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- Wheeler, Brannon M. (1996). Applying the Canon in Islam: The Authorization and Maintenance of Interpretive Reasoning in Ḥanafī Scholarship. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-2395-1.

Further reading

- Cilardo, Agostino (2014), Maliki Fiqh, in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God (2 vols.), Edited by C. Fitzpatrick and A. Walker, Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO

- Chouki El Hamel (2012), Slavery in Maliki School in the Maghreb, in Black Morocco: A History of Slavery, Race, and Islam, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107025776

- Thomas Eich (2009), Induced Miscarriage (Abortion) in Early Maliki and Hanafi Fiqh, Islamic Law & Society, Vol. 16, pp. 302–336

- Janina Safran (2003), Rules of purity and confessional boundaries: Maliki debates about the pollution of the Christian, History of religions, Vol. 42 No. 3, pp. 197–212

- FH Ruxton (1913), The Convert's Status in Maliki Law, The Muslim World, Vol 3, Issue 1, pp. 37–40,

External links

- Partial Translation of Mālik's Al-Muwaṭṭah University of Southern California

- Malikiyyah Bulend Shanay, Lancaster University

- Biographical summary of Imam Mālik

- Al-Risalah of 'Abdullah ibn Abi Zayd al-Qayrawani 10th century Maliki text on Islamic law, Translated by Aisha Bewley

- French translations of a variety of important Mālikī source texts (in French)