Maltese Baroque architecture

Maltese Baroque architecture is the form of

The Baroque style began to be replaced by neoclassical architecture and other styles in the early 19th century, when Malta was under British rule. Despite this, Baroque elements continued to influence traditional Maltese architecture. Many churches continued to the built in the Baroque style throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and to a lesser extent in the 21st century.[2]

Background

Prior to the introduction of the Baroque style in Malta, the predominant architectural style on the island was

Seventeenth century

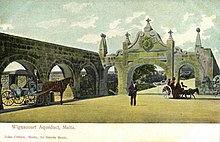

According to historian Giovanni Bonello, the Baroque style was probably introduced in Malta by the Bolognese architect and engineer Bontadino de Bontadini in the beginning of the 17th century. In July 1612, Bontadini was entrusted with the construction of the Wignacourt Aqueduct, a project which was completed on 21 April 1615. The aqueduct's decorative elements, namely the Wignacourt Arch, three water towers and several fountains, are probably the earliest representations of the Baroque style in Malta.[6]

However, according to

From the 1660s onwards, many churches began to be constructed in the Baroque style, and they were characterized by large domes and belfries which dominated the skyline of the towns and villages.

Meanwhile, many existing churches were redecorated in the Baroque style. The interior of Saint John's Co-Cathedral, then the Order's conventual church, was extensively embellished in the 1660s by the Calabrian artist Mattia Preti, although the Mannerist exterior was retained.[12]

Eighteenth century

The Baroque style was the most popular architectural style in Malta throughout the 18th century. Examples of Baroque buildings from the first half of the century include the Banca Giuratale in Valletta (1721),[13] Fort Manoel in Gżira (1723–33)[14] and Casa Leoni in Santa Venera (1730).[15]

An example of Baroque town planning was

High Baroque was popular throughout the magistracy of Manuel Pinto da Fonseca, and buildings constructed during his reign include Auberge de Castille (1741–45), the Pinto Stores (1752) and the Castellania (1757–60).[17] Auberge de Castille was designed by the Maltese architect Andrea Belli, and it replaced Girolamo Cassar's earlier Mannerist building. The auberge's ornate façade and the steps leading to the doorway were designed to be imposing,[18] and it is regarded as the most monumental Baroque building in Malta.[8]

Nineteenth, twentieth and twenty-first centuries

Neoclassical architecture and other architectural styles were introduced in Malta in the late 18th century, and they were popularized when the island was under British rule in the early decades of the 19th century.[19] Despite the introduction of these new styles, Baroque remained popular for the nobility's palaces, and Baroque features began to appear in traditional Maltese townhouses,[8] such as Casa Nasciaro.[20]

The Baroque style remained the predominant style for most Maltese churches throughout the 19th and most of the 20th centuries. Examples of these include the Mellieħa Parish Church (1881–98)[21] and the Rotunda of Xewkija (1952–78). A few churches built in the 21st century still include significant Baroque elements, such as the Santa Venera Parish Church which was constructed between 1990 and 2005.[22]

Historian Giovanni Bonello ranks Maltese Baroque as one of the three "treasures" of Maltese architecture, along with the megalithic temples and the fortifications.[23]

See also

Further reading

References

- ^ https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/bitstream/handle/123456789/12023/OA%20Appunti%20sull'%20architettura%20religiosa%20a%20Malta%20in%20eta%20Barocca.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y[permanent dead link]

- ^ https://susanklaiber.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/eahn2018_proceedings.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- JSTOR 43620704.

- ^ Mangion, Giovanni (1973). "Girolamo Cassar Architetto maltese del cinquecento" (PDF). Melita Historica (in Italian). 6 (2). Malta Historical Society: 192–200. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2016.

- ^ Hughes, J. Quentin (1953). "The influence of Italian mannerism upon Maltese architecture" (PDF). Melita Historica. 1 (2): 110.

- ISBN 9789993210276.

- ISBN 9789990958157.

- ^ a b c d "Baroque Architecture". Culture Malta. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016.

- ^ https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/bitstream/handle/123456789/40464/Ephemeral_manifestations_in_Baroque_Malta_2011.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [dead link]

- ^ "One World – Protecting the most significant buildings, monuments and features of Valletta (97)". Times of Malta. 14 March 2009. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016.

- ISBN 9789993291329.

- ^ "History of St John's – A Legacy of the Knights of Malta". St. John's Co-Cathedral. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Municipal Palace/ Banca Guratale" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "Couvre Porte – Fort Manoel" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "Locality Information". lc.gov.mt. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015.

- ^ De Lucca, Denis (1979). "Mdina: Mondion's master plan for the old city". Heritage: An Encyclopedia of Maltese Culture and Civilization. 1. Midsea Books Ltd: 53–56.

- ^ Thake, Conrad Gerald (1994). "Architectural Scenography in 18th-Century Mdina". Journal of the Malta Historical Society. Melita Historica. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016.

- ^ "Il-Palazzi tal-Belt Valletta". Air Malta (in Maltese). Archived from the original on 17 June 2016.

- ISBN 9789990932065.

- ^ "Baroque Naxxar Townhouse". Times of Malta. 12 April 2012. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015.

- ^ "Places Of Interest". Explore Mellieha. Archived from the original on 27 August 2015.

- ^ "St Venera To inaugurate new Lm600,000 church on Sunday". The Malta Independent. 14 July 2005. Archived from the original on 23 July 2016.

- ^ Bonello, Giovanni (18 November 2012). "Let's hide the majestic bastions". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.