Mammal

| Mammals Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Amniota |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Mammaliaformes |

| Class: | Mammalia Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Living subgroups | |

| |

A mammal (from

.The largest orders of mammals, by number of species, are the

Mammals are the only living members of

The basic mammalian body type is

.Most mammals are

Domestication of many types of mammals by humans played a major role in the Neolithic Revolution, and resulted in farming replacing hunting and gathering as the primary source of food for humans. This led to a major restructuring of human societies from nomadic to sedentary, with more co-operation among larger and larger groups, and ultimately the development of the first civilizations. Domesticated mammals provided, and continue to provide, power for transport and agriculture, as well as food (meat and dairy products), fur, and leather. Mammals are also hunted and raced for sport, kept as pets and working animals of various types, and are used as model organisms in science. Mammals have been depicted in art since Paleolithic times, and appear in literature, film, mythology, and religion. Decline in numbers and extinction of many mammals is primarily driven by human poaching and habitat destruction, primarily deforestation.

Classification

Mammal classification has been through several revisions since Carl Linnaeus initially defined the class, and at present, no classification system is universally accepted. McKenna & Bell (1997) and Wilson & Reeder (2005) provide useful recent compendiums.[2] Simpson (1945)[3] provides systematics of mammal origins and relationships that had been taught universally until the end of the 20th century. However, since 1945, a large amount of new and more detailed information has gradually been found: The

Most mammals, including the six most species-rich

Definitions

The word "

McKenna/Bell classification

In 1997, the mammals were comprehensively revised by

In the following list,

Class Mammalia

- Subclass Prototheria: monotremes: echidnas and the platypus

- Subclass Theriiformes: live-bearing mammals and their prehistoric relatives

- Infraclass †Allotheria: multituberculates

- Infraclass †Eutriconodonta: eutriconodonts

- Infraclass Holotheria: modern live-bearing mammals and their prehistoric relatives

- Superlegion †Kuehneotheria

- Supercohort Theria: live-bearing mammals

- Cohort Marsupialia: marsupials

- Magnorder Australidelphia: Australian marsupials and the monito del monte

- Magnorder Ameridelphia: New World marsupials. Now considered paraphyletic, with shrew opossums being closer to australidelphians.[16]

- Cohort Placentalia: placentals

- Magnorder Xenarthra: xenarthrans

- Magnorder Epitheria: epitheres

- Superorder †Leptictida

- Superorder Preptotheria

- Grandorder Anagalida: lagomorphs, rodents and elephant shrews

- Grandorder creodontsand relatives

- Grandorder Lipotyphla: insectivorans

- Grandorder Archonta: bats, primates, colugos and treeshrews (now considered paraphyletic, with bats being closer to other groups)

- Grandorder Euungulata: ungulates

- Order Tubulidentata incertae sedis: aardvark

- Mirorder condylarths, whales and artiodactyls(even-toed ungulates)

- Mirorder †Meridiungulata: South American ungulates

- Mirorder

- Order

- Cohort

- Superlegion †

Molecular classification of placentals

As of the early 21st century, molecular studies based on DNA analysis have suggested new relationships among mammal families. Most of these findings have been independently validated by retrotransposon presence/absence data.[18] Classification systems based on molecular studies reveal three major groups or lineages of placental mammals—Afrotheria, Xenarthra and Boreoeutheria—which diverged in the Cretaceous. The relationships between these three lineages is contentious, and all three possible hypotheses have been proposed with respect to which group is basal. These hypotheses are Atlantogenata (basal Boreoeutheria), Epitheria (basal Xenarthra) and Exafroplacentalia (basal Afrotheria).[19] Boreoeutheria in turn contains two major lineages—Euarchontoglires and Laurasiatheria.

Estimates for the divergence times between these three placental groups range from 105 to 120 million years ago, depending on the type of DNA used (such as

| Tarver et al. 2016[21] | Sandra Álvarez-Carretero et al. 2022[22][23] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Evolution

Origins

Synapsida, a clade that contains mammals and their extinct relatives, originated during the Pennsylvanian subperiod (~323 million to ~300 million years ago), when they split from the reptile lineage. Crown group mammals evolved from earlier mammaliaforms during the Early Jurassic. The cladogram takes Mammalia to be the crown group.[24]

| Mammaliaformes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evolution from older amniotes

The first fully terrestrial vertebrates were amniotes. Like their amphibious early tetrapod predecessors, they had lungs and limbs. Amniotic eggs, however, have internal membranes that allow the developing embryo to breathe but keep water in. Hence, amniotes can lay eggs on dry land, while amphibians generally need to lay their eggs in water.

The first amniotes apparently arose in the Pennsylvanian subperiod of the

Therapsids, a group of synapsids, evolved in the Middle Permian, about 265 million years ago, and became the dominant land vertebrates.[28] They differ from basal eupelycosaurs in several features of the skull and jaws, including: larger skulls and incisors which are equal in size in therapsids, but not for eupelycosaurs.[28] The therapsid lineage leading to mammals went through a series of stages, beginning with animals that were very similar to their early synapsid ancestors and ending with probainognathian cynodonts, some of which could easily be mistaken for mammals. Those stages were characterized by:[30]

- The gradual development of a bony secondary palate.

- Abrupt acquisition of endothermy among Mammaliamorpha, thus prior to the origin of mammals by 30–50 millions of years [31].

- Progression towards an erect limb posture, which would increase the animals' stamina by avoiding Carrier's constraint. But this process was slow and erratic: for example, all herbivorous nonmammaliaform therapsids retained sprawling limbs (some late forms may have had semierect hind limbs); Permian carnivorous therapsids had sprawling forelimbs, and some late Permian ones also had semisprawling hindlimbs. In fact, modern monotremes still have semisprawling limbs.

- The dentary gradually became the main bone of the lower jaw which, by the Triassic, progressed towards the fully mammalian jaw (the lower consisting only of the dentary) and middle ear (which is constructed by the bones that were previously used to construct the jaws of reptiles).

First mammals

The Permian–Triassic extinction event about 252 million years ago, which was a prolonged event due to the accumulation of several extinction pulses, ended the dominance of carnivorous therapsids.[32] In the early Triassic, most medium to large land carnivore niches were taken over by archosaurs[33] which, over an extended period (35 million years), came to include the crocodylomorphs,[34] the pterosaurs and the dinosaurs;[35] however, large cynodonts like Trucidocynodon and traversodontids still occupied large sized carnivorous and herbivorous niches respectively. By the Jurassic, the dinosaurs had come to dominate the large terrestrial herbivore niches as well.[36]

The first mammals (in Kemp's sense) appeared in the Late Triassic epoch (about 225 million years ago), 40 million years after the first therapsids. They expanded out of their nocturnal

The oldest-known fossil among the Eutheria ("true beasts") is the small shrewlike Juramaia sinensis, or "Jurassic mother from China", dated to 160 million years ago in the late Jurassic.[42] A later eutherian relative, Eomaia, dated to 125 million years ago in the early Cretaceous, possessed some features in common with the marsupials but not with the placentals, evidence that these features were present in the last common ancestor of the two groups but were later lost in the placental lineage.[43] In particular, the epipubic bones extend forwards from the pelvis. These are not found in any modern placental, but they are found in marsupials, monotremes, other nontherian mammals and Ukhaatherium, an early Cretaceous animal in the eutherian order Asioryctitheria. This also applies to the multituberculates.[44] They are apparently an ancestral feature, which subsequently disappeared in the placental lineage. These epipubic bones seem to function by stiffening the muscles during locomotion, reducing the amount of space being presented, which placentals require to contain their fetus during gestation periods. A narrow pelvic outlet indicates that the young were very small at birth and therefore pregnancy was short, as in modern marsupials. This suggests that the placenta was a later development.[45]

One of the earliest-known monotremes was

Earliest appearances of features

Hadrocodium, whose fossils date from approximately 195 million years ago, in the early Jurassic, provides the first clear evidence of a jaw joint formed solely by the squamosal and dentary bones; there is no space in the jaw for the articular, a bone involved in the jaws of all early synapsids.[49]

The earliest clear evidence of hair or fur is in fossils of

When

The evolution of erect limbs in mammals is incomplete—living and fossil monotremes have sprawling limbs. The parasagittal (nonsprawling) limb posture appeared sometime in the late Jurassic or early Cretaceous; it is found in the eutherian Eomaia and the metatherian Sinodelphys, both dated to 125 million years ago.

It has been suggested that the original function of lactation (milk production) was to keep eggs moist. Much of the argument is based on monotremes, the egg-laying mammals.[61][62] In human females, mammary glands become fully developed during puberty, regardless of pregnancy.[63]

Rise of the mammals

Therian mammals took over the medium- to large-sized ecological niches in the Cenozoic, after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event approximately 66 million years ago emptied ecological space once filled by non-avian dinosaurs and other groups of reptiles, as well as various other mammal groups,[65] and underwent an exponential increase in body size (megafauna).[66] Then mammals diversified very quickly; both birds and mammals show an exponential rise in diversity.[65] For example, the earliest-known bat dates from about 50 million years ago, only 16 million years after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs.[67]

Molecular phylogenetic studies initially suggested that most placental orders diverged about 100 to 85 million years ago and that modern families appeared in the period from the late

The earliest-known ancestor of primates is

Anatomy

Distinguishing features

Living mammal species can be identified by the presence of sweat glands, including those that are specialized to produce milk to nourish their young.[74] In classifying fossils, however, other features must be used, since soft tissue glands and many other features are not visible in fossils.[75]

Many traits shared by all living mammals appeared among the earliest members of the group:

- Middle ear – In crown-group mammals, sound is carried from the eardrum by a chain of three bones, the malleus, the incus and the stapes. Ancestrally, the malleus and the incus are derived from the articular and the quadrate bones that constituted the jaw joint of early therapsids.[76]

- Tooth replacement – Teeth can be replaced once (diphyodonty) or (as in toothed whales and murid rodents) not at all (monophyodonty).[77] Elephants, manatees, and kangaroos continually grow new teeth throughout their life (polyphyodonty).[78]

- Prismatic enamel – The enamel coating on the surface of a tooth consists of prisms, solid, rod-like structures extending from the dentin to the tooth's surface.[79]

- Occipital condyles – Two knobs at the base of the skull fit into the topmost neck vertebra; most other tetrapods, in contrast, have only one such knob.[80]

For the most part, these characteristics were not present in the Triassic ancestors of the mammals.[81] Nearly all mammaliaforms possess an epipubic bone, the exception being modern placentals.[82]

Sexual dimorphism

On average, male mammals are larger than females, with males being at least 10% larger than females in over 45% of investigated species. Most mammalian orders also exhibit male-biased sexual dimorphism, although some orders do not show any bias or are significantly female-biased (Lagomorpha). Sexual size dimorphism increases with body size across mammals (Rensch's rule), suggesting that there are parallel selection pressures on both male and female size. Male-biased dimorphism relates to sexual selection on males through male–male competition for females, as there is a positive correlation between the degree of sexual selection, as indicated by mating systems, and the degree of male-biased size dimorphism. The degree of sexual selection is also positively correlated with male and female size across mammals. Further, parallel selection pressure on female mass is identified in that age at weaning is significantly higher in more polygynous species, even when correcting for body mass. Also, the reproductive rate is lower for larger females, indicating that fecundity selection selects for smaller females in mammals. Although these patterns hold across mammals as a whole, there is considerable variation across orders.[83]

Biological systems

The majority of mammals have seven cervical vertebrae (bones in the neck). The exceptions are the manatee and the two-toed sloth, which have six, and the three-toed sloth which has nine.[84] All mammalian brains possess a neocortex, a brain region unique to mammals.[85] Placental brains have a corpus callosum, unlike monotremes and marsupials.[86]

Circulatory systems

The mammalian heart has four chambers, two upper atria, the receiving chambers, and two lower ventricles, the discharging chambers.[87] The heart has four valves, which separate its chambers and ensures blood flows in the correct direction through the heart (preventing backflow). After gas exchange in the pulmonary capillaries (blood vessels in the lungs), oxygen-rich blood returns to the left atrium via one of the four pulmonary veins. Blood flows nearly continuously back into the atrium, which acts as the receiving chamber, and from here through an opening into the left ventricle. Most blood flows passively into the heart while both the atria and ventricles are relaxed, but toward the end of the ventricular relaxation period, the left atrium will contract, pumping blood into the ventricle. The heart also requires nutrients and oxygen found in blood like other muscles, and is supplied via coronary arteries.[88]

Respiratory systems

The

Integumentary systems

The

Digestive systems

Herbivores have developed a diverse range of physical structures to facilitate the

The stomach of

Excretory and genitourinary systems

The mammalian

Sound production

As in all other tetrapods, mammals have a

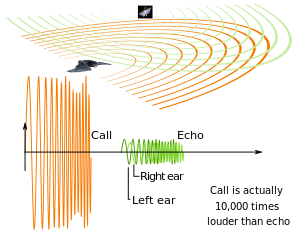

Some mammals have a large larynx and thus a low-pitched voice, namely the hammer-headed bat (Hypsignathus monstrosus) where the larynx can take up the entirety of the thoracic cavity while pushing the lungs, heart, and trachea into the abdomen.[107] Large vocal pads can also lower the pitch, as in the low-pitched roars of big cats.[108] The production of infrasound is possible in some mammals such as the African elephant (Loxodonta spp.) and baleen whales.[109][110] Small mammals with small larynxes have the ability to produce ultrasound, which can be detected by modifications to the middle ear and cochlea. Ultrasound is inaudible to birds and reptiles, which might have been important during the Mesozoic, when birds and reptiles were the dominant predators. This private channel is used by some rodents in, for example, mother-to-pup communication, and by bats when echolocating. Toothed whales also use echolocation, but, as opposed to the vocal membrane that extends upward from the vocal folds, they have a melon to manipulate sounds. Some mammals, namely the primates, have air sacs attached to the larynx, which may function to lower the resonances or increase the volume of sound.[106]

The vocal production system is controlled by the cranial nerve nuclei in the brain, and supplied by the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the superior laryngeal nerve, branches of the vagus nerve. The vocal tract is supplied by the hypoglossal nerve and facial nerves. Electrical stimulation of the periaqueductal gray (PEG) region of the mammalian midbrain elicit vocalizations. The ability to learn new vocalizations is only exemplified in humans, seals, cetaceans, elephants and possibly bats; in humans, this is the result of a direct connection between the motor cortex, which controls movement, and the motor neurons in the spinal cord.[106]

Fur

The primary function of the fur of mammals is thermoregulation. Others include protection, sensory purposes, waterproofing, and camouflage.[111] Different types of fur serve different purposes:[91]: 99

- Definitive – which may be shed after reaching a certain length

- Vibrissae – sensory hairs, most commonly whiskers

- Pelage – guard hairs, under-fur, and awn hair

- Spines – stiff guard hair used for defense (such as in porcupines)

- mane)

- Velli – often called "down fur" which insulates newborn mammals

- Wool – long, soft and often curly

Thermoregulation

Hair length is not a factor in thermoregulation: for example, some tropical mammals such as sloths have the same length of fur length as some arctic mammals but with less insulation; and, conversely, other tropical mammals with short hair have the same insulating value as arctic mammals. The denseness of fur can increase an animal's insulation value, and arctic mammals especially have dense fur; for example, the

Coloration

Mammalian coats are colored for a variety of reasons, the major selective pressures including

Camouflage is a powerful influence in a large number of mammals, as it helps to conceal individuals from predators or prey.

Aposematism, warning off possible predators, is the most likely explanation of the black-and-white pelage of many mammals which are able to defend themselves, such as in the foul-smelling skunk and the powerful and aggressive honey badger.[118] Coat color is sometimes sexually dimorphic, as in many primate species.[119] Differences in female and male coat color may indicate nutrition and hormone levels, important in mate selection.[120] Coat color may influence the ability to retain heat, depending on how much light is reflected. Mammals with a darker colored coat can absorb more heat from solar radiation, and stay warmer, and some smaller mammals, such as voles, have darker fur in the winter. The white, pigmentless fur of arctic mammals, such as the polar bear, may reflect more solar radiation directly onto the skin.[91]: 166–167 [111] The dazzling black-and-white striping of zebras appear to provide some protection from biting flies.[121]

Reproductive system

Mammals are solely

The ancestral condition for mammal reproduction is the birthing of relatively undeveloped young, either through direct

Viviparous mammals are in the subclass Theria; those living today are in the marsupial and placental infraclasses. Marsupials have a short

The mammary glands of mammals are specialized to produce milk, the primary source of nutrition for newborns. The monotremes branched early from other mammals and do not have the teats seen in most mammals, but they do have mammary glands. The young lick the milk from a mammary patch on the mother's belly.[136] Compared to placental mammals, the milk of marsupials changes greatly in both production rate and in nutrient composition, due to the underdeveloped young. In addition, the mammary glands have more autonomy allowing them to supply separate milks to young at different development stages.[137] Lactose is the main sugar in placental mammal milk while monotreme and marsupial milk is dominated by oligosaccharides.[138] Weaning is the process in which a mammal becomes less dependent on their mother's milk and more on solid food.[139]

Endothermy

Nearly all mammals are

Species lifespan

Among mammals, species maximum lifespan varies significantly (for example the

Locomotion

Terrestrial

Most vertebrates—the amphibians, the reptiles and some mammals such as humans and bears—are

Animals will use different gaits for different speeds, terrain and situations. For example, horses show four natural gaits, the slowest

Arboreal

Arboreal animals frequently have elongated limbs that help them cross gaps, reach fruit or other resources, test the firmness of support ahead and, in some cases, to brachiate (swing between trees).[157] Many arboreal species, such as tree porcupines, silky anteaters, spider monkeys, and possums, use prehensile tails to grasp branches. In the spider monkey, the tip of the tail has either a bare patch or adhesive pad, which provides increased friction. Claws can be used to interact with rough substrates and reorient the direction of forces the animal applies. This is what allows squirrels to climb tree trunks that are so large to be essentially flat from the perspective of such a small animal. However, claws can interfere with an animal's ability to grasp very small branches, as they may wrap too far around and prick the animal's own paw. Frictional gripping is used by primates, relying upon hairless fingertips. Squeezing the branch between the fingertips generates frictional force that holds the animal's hand to the branch. However, this type of grip depends upon the angle of the frictional force, thus upon the diameter of the branch, with larger branches resulting in reduced gripping ability. To control descent, especially down large diameter branches, some arboreal animals such as squirrels have evolved highly mobile ankle joints that permit rotating the foot into a 'reversed' posture. This allows the claws to hook into the rough surface of the bark, opposing the force of gravity. Small size provides many advantages to arboreal species: such as increasing the relative size of branches to the animal, lower center of mass, increased stability, lower mass (allowing movement on smaller branches) and the ability to move through more cluttered habitat.[157] Size relating to weight affects gliding animals such as the sugar glider.[158] Some species of primate, bat and all species of sloth achieve passive stability by hanging beneath the branch. Both pitching and tipping become irrelevant, as the only method of failure would be losing their grip.[157]

Aerial

Bats are the only mammals that can truly fly. They fly through the air at a constant speed by moving their wings up and down (usually with some fore-aft movement as well). Because the animal is in motion, there is some airflow relative to its body which, combined with the velocity of the wings, generates a faster airflow moving over the wing. This generates a lift force vector pointing forwards and upwards, and a drag force vector pointing rearwards and upwards. The upwards components of these counteract gravity, keeping the body in the air, while the forward component provides thrust to counteract both the drag from the wing and from the body as a whole.[159]

The wings of bats are much thinner and consist of more bones than those of birds, allowing bats to maneuver more accurately and fly with more lift and less drag.[160][161] By folding the wings inwards towards their body on the upstroke, they use 35% less energy during flight than birds.[162] The membranes are delicate, ripping easily; however, the tissue of the bat's membrane is able to regrow, such that small tears can heal quickly.[163] The surface of their wings is equipped with touch-sensitive receptors on small bumps called Merkel cells, also found on human fingertips. These sensitive areas are different in bats, as each bump has a tiny hair in the center, making it even more sensitive and allowing the bat to detect and collect information about the air flowing over its wings, and to fly more efficiently by changing the shape of its wings in response.[164]

Fossorial and subterranean

A fossorial (from Latin fossor, meaning "digger") is an animal adapted to digging which lives primarily, but not solely, underground. Some examples are

Fossorial mammals have a fusiform body, thickest at the shoulders and tapering off at the tail and nose. Unable to see in the dark burrows, most have degenerated eyes, but degeneration varies between species;

Many fossorial mammals such as shrews, hedgehogs, and moles were classified under the now obsolete order Insectivora.[167]

Aquatic

Fully aquatic mammals, the cetaceans and sirenians, have lost their legs and have a tail fin to propel themselves through the water. Flipper movement is continuous. Whales swim by moving their tail fin and lower body up and down, propelling themselves through vertical movement, while their flippers are mainly used for steering. Their skeletal anatomy allows them to be fast swimmers. Most species have a dorsal fin to prevent themselves from turning upside-down in the water.[168][169] The flukes of sirenians are raised up and down in long strokes to move the animal forward, and can be twisted to turn. The forelimbs are paddle-like flippers which aid in turning and slowing.[170]

Behavior

Communication and vocalization

Many mammals communicate by vocalizing. Vocal communication serves many purposes, including in mating rituals, as

Mammals signal by a variety of means. Many give visual

Feeding

To maintain a high constant body temperature is energy expensive—mammals therefore need a nutritious and plentiful diet. While the earliest mammals were probably predators, different species have since adapted to meet their dietary requirements in a variety of ways. Some eat other animals—this is a

The size of an animal is also a factor in determining diet type (Allen's rule). Since small mammals have a high ratio of heat-losing surface area to heat-generating volume, they tend to have high energy requirements and a high metabolic rate. Mammals that weigh less than about 18 ounces (510 g; 1.1 lb) are mostly insectivorous because they cannot tolerate the slow, complex digestive process of an herbivore. Larger animals, on the other hand, generate more heat and less of this heat is lost. They can therefore tolerate either a slower collection process (carnivores that feed on larger vertebrates) or a slower digestive process (herbivores).[196] Furthermore, mammals that weigh more than 18 ounces (510 g; 1.1 lb) usually cannot collect enough insects during their waking hours to sustain themselves. The only large insectivorous mammals are those that feed on huge colonies of insects (ants or termites).[197]

Some mammals are omnivores and display varying degrees of carnivory and herbivory, generally leaning in favor of one more than the other. Since plants and meat are digested differently, there is a preference for one over the other, as in bears where some species may be mostly carnivorous and others mostly herbivorous.[199] They are grouped into three categories: mesocarnivory (50–70% meat), hypercarnivory (70% and greater of meat), and hypocarnivory (50% or less of meat). The dentition of hypocarnivores consists of dull, triangular carnassial teeth meant for grinding food. Hypercarnivores, however, have conical teeth and sharp carnassials meant for slashing, and in some cases strong jaws for bone-crushing, as in the case of hyenas, allowing them to consume bones; some extinct groups, notably the Machairodontinae, had saber-shaped canines.[198]

Some physiological carnivores consume plant matter and some physiological herbivores consume meat. From a behavioral aspect, this would make them omnivores, but from the physiological standpoint, this may be due to zoopharmacognosy. Physiologically, animals must be able to obtain both energy and nutrients from plant and animal materials to be considered omnivorous. Thus, such animals are still able to be classified as carnivores and herbivores when they are just obtaining nutrients from materials originating from sources that do not seemingly complement their classification.[200] For example, it is well documented that some ungulates such as giraffes, camels, and cattle, will gnaw on bones to consume particular minerals and nutrients.[201] Also, cats, which are generally regarded as obligate carnivores, occasionally eat grass to regurgitate indigestible material (such as hairballs), aid with hemoglobin production, and as a laxative.[202]

Many mammals, in the absence of sufficient food requirements in an environment, suppress their metabolism and conserve energy in a process known as

Drinking

By necessity, terrestrial animals in captivity become accustomed to drinking water, but most free-roaming animals stay hydrated through the fluids and moisture in fresh food,[207] and learn to actively seek foods with high fluid content.[208] When conditions impel them to drink from bodies of water, the methods and motions differ greatly among species.[209]

Intelligence

In intelligent mammals, such as

Self-awareness appears to be a sign of abstract thinking. Self-awareness, although not well-defined, is believed to be a precursor to more advanced processes such as metacognitive reasoning. The traditional method for measuring this is the mirror test, which determines if an animal possesses the ability of self-recognition.[221] Mammals that have passed the mirror test include Asian elephants (some pass, some do not);[222] chimpanzees;[223] bonobos;[224] orangutans;[225] humans, from 18 months (mirror stage);[226] common bottlenose dolphins;[a][227] orcas;[228] and false killer whales.[228]

Social structure

Eusociality is the highest level of social organization. These societies have an overlap of adult generations, the division of reproductive labor and cooperative caring of young. Usually insects, such as bees, ants and termites, have eusocial behavior, but it is demonstrated in two rodent species: the naked mole-rat[229] and the Damaraland mole-rat.[230]

Presociality is when animals exhibit more than just sexual interactions with members of the same species, but fall short of qualifying as eusocial. That is, presocial animals can display communal living, cooperative care of young, or primitive division of reproductive labor, but they do not display all of the three essential traits of eusocial animals. Humans and some species of

A fission–fusion society is a society that changes frequently in its size and composition, making up a permanent social group called the "parent group". Permanent social networks consist of all individual members of a community and often varies to track changes in their environment. In a fission–fusion society, the main parent group can fracture (fission) into smaller stable subgroups or individuals to adapt to environmental or social circumstances. For example, a number of males may break off from the main group in order to hunt or forage for food during the day, but at night they may return to join (fusion) the primary group to share food and partake in other activities. Many mammals exhibit this, such as primates (for example orangutans and spider monkeys),[233] elephants,[234] spotted hyenas,[235] lions,[236] and dolphins.[237]

Solitary animals defend a territory and avoid social interactions with the members of its species, except during breeding season. This is to avoid resource competition, as two individuals of the same species would occupy the same niche, and to prevent depletion of food.[238] A solitary animal, while foraging, can also be less conspicuous to predators or prey.[239]

In a

Some mammals are perfectly monogamous, meaning that they mate for life and take no other partners (even after the original mate's death), as with wolves, Eurasian beavers, and otters.[244][245] There are three types of polygamy: either one or multiple dominant males have breeding rights (polygyny), multiple males that females mate with (polyandry), or multiple males have exclusive relations with multiple females (polygynandry). It is much more common for polygynous mating to happen, which, excluding leks, are estimated to occur in up to 90% of mammals.[246] Lek mating occurs when males congregate around females and try to attract them with various courtship displays and vocalizations, as in harbor seals.[247]

All

Humans and other mammals

In human culture

Non-human mammals play a wide variety of roles in human culture. They are the most popular of pets, with tens of millions of dogs, cats and other animals including rabbits and mice kept by families around the world.[249][250][251] Mammals such as mammoths, horses and deer are among the earliest subjects of art, being found in Upper Paleolithic cave paintings such as at Lascaux.[252] Major artists such as Albrecht Dürer, George Stubbs and Edwin Landseer are known for their portraits of mammals.[253] Many species of mammals have been hunted for sport and for food; deer and wild boar are especially popular as game animals.[254][255][256] Mammals such as horses and dogs are widely raced for sport, often combined with betting on the outcome.[257][258] There is a tension between the role of animals as companions to humans, and their existence as individuals with rights of their own.[259] Mammals further play a wide variety of roles in literature,[260][261][262] film,[263] mythology, and religion.[264][265][266]

Uses and importance

The domestication of mammals was instrumental in the Neolithic development of agriculture and of civilization, causing farmers to replace hunter-gatherers around the world.[b][268] This transition from hunting and gathering to herding flocks and growing crops was a major step in human history. The new agricultural economies, based on domesticated mammals, caused "radical restructuring of human societies, worldwide alterations in biodiversity, and significant changes in the Earth's landforms and its atmosphere... momentous outcomes".[269]

Mammals serve a major role in science as

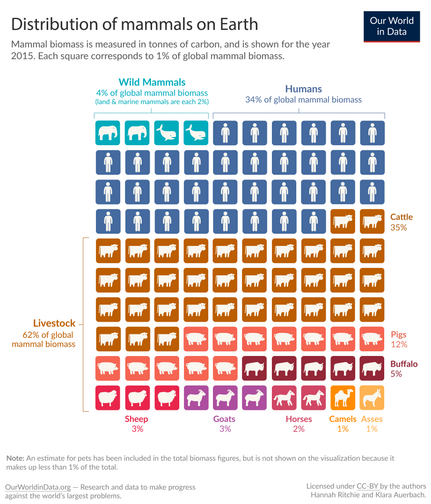

Despite the benefits domesticated mammals had for human development, humans have an increasingly detrimental effect on wild mammals across the world. It has been estimated that the mass of all wild mammals has declined to only 4% of all mammals, with 96% of mammals being humans and their livestock now (see figure). In fact, terrestrial wild mammals make up only 2% of all mammals.[284][285]

Hybrids

Hybrids are offspring resulting from the breeding of two genetically distinct individuals, which usually will result in a high degree of heterozygosity, though hybrid and heterozygous are not synonymous. The deliberate or accidental hybridizing of two or more species of closely related animals through captive breeding is a human activity which has been in existence for millennia and has grown for economic purposes.[286] Hybrids between different subspecies within a species (such as between the Bengal tiger and Siberian tiger) are known as intra-specific hybrids. Hybrids between different species within the same genus (such as between lions and tigers) are known as interspecific hybrids or crosses. Hybrids between different genera (such as between sheep and goats) are known as intergeneric hybrids.[287] Natural hybrids will occur in hybrid zones, where two populations of species within the same genera or species living in the same or adjacent areas will interbreed with each other. Some hybrids have been recognized as species, such as the red wolf (though this is controversial).[288]

Threats

The loss of species from ecological communities,

Various species are predicted to

Attention is being given to endangered species globally, notably through the Convention on Biological Diversity, otherwise known as the Rio Accord, which includes 189 signatory countries that are focused on identifying endangered species and habitats.[319] Another notable conservation organization is the IUCN, which has a membership of over 1,200 governmental and non-governmental organizations.[320]

Recent extinctions can be directly attributed to human influences.[321][295] The IUCN characterizes 'recent' extinction as those that have occurred past the cut-off point of 1500,[322] and around 80 mammal species have gone extinct since that time and 2015.[323] Some species, such as the Père David's deer[324] are extinct in the wild, and survive solely in captive populations. Other species, such as the Florida panther, are ecologically extinct, surviving in such low numbers that they essentially have no impact on the ecosystem.[325]: 318 Other populations are only locally extinct (extirpated), still existing elsewhere, but reduced in distribution,[325]: 75–77 as with the extinction of gray whales in the Atlantic.[326]

See also

- List of mammal genera – living mammals

- List of mammalogists

- List of monotremes and marsupials

- List of placental mammals

- List of prehistoric mammals

- List of endangered mammals

- Lists of mammals by population size

- Lists of mammals by region

- Mammals described in the 2000s

- Mammals in culture

- Small mammal

Notes

- ^ Decreased latency to approach the mirror, repetitious head circling and close viewing of the marked areas were considered signs of self-recognition since they do not have arms and cannot touch the marked areas.[227]

- ^ Diamond discussed this matter further in his 1997 book Guns, Germs, and Steel.[267]

References

- ^ Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1879). "mamma". A Latin Dictionary. Perseus Digital Library.

- ISBN 978-1-284-03209-3.

- ^ Simpson GG (1945). "Principles of classification, and a classification of mammals". American Museum of Natural History. 85.

- ^ JSTOR 4523980.

- ^ OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "Mammals". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). April 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- .

- .

- ISBN 978-1-345-18248-4.

- S2CID 83973542.

- OCLC 232311794.

- S2CID 131236175.

- S2CID 29846648. Archived from the original(PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ISSN 1064-7554.

- OCLC 37345734.

- PMID 20668664.

- PMID 16515367.

- ^ PMID 19286970.

- PMID 12552136.

- PMID 26733575.

- S2CID 245438816.

- . Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- S2CID 4428972.

- S2CID 4369342.

- ^ "Amniota – Palaeos". Archived from the original on 20 December 2010.

- ^ "Synapsida overview – Palaeos". Archived from the original on 20 December 2010.

- ^ S2CID 3184629. Archived from the original(PDF) on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-87474-524-5.

- OCLC 10710687.

- S2CID 236245230.

- doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(03)00082-5. Archived from the original(PDF) on 25 October 2007.

- S2CID 13393888.

- ^ Gauthier JA (1986). "Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds". In Padian K (ed.). The Origin of Birds and the Evolution of Flight. Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences. Vol. 8. San Francisco: California Academy of Sciences. pp. 1–55.

- JSTOR 3889336.

- S2CID 129654916.

- OCLC 892735337.

- ^ Bakalar N (2006). "Jurassic "Beaver" Found; Rewrites History of Mammals". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 3 March 2006. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- PMID 23097513.

- S2CID 4317817.

- ^ Pickrell J (2003). "Oldest Marsupial Fossil Found in China". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 17 December 2003. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ S2CID 205225806.

- S2CID 4330626.

- ^ S2CID 205026882.

- ISBN 978-1-4214-0643-5.

- PMID 18216270.

- OCLC 33842474.

- PMID 22577734.

- ^ OCLC 646769601.

- ^ Brink AS (1955). "A study on the skeleton of Diademodon". Palaeontologia Africana. 3: 3–39.

- OCLC 8613180.

- ^ Estes R (1961). "Cranial anatomy of the cynodont reptile Thrinaxodon liorhinus". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology (1253): 165–180.

- ^ "Thrinaxodon: The Emerging Mammal". National Geographic Daily News. 11 February 2009. Archived from the original on 14 February 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ .

- .

- OCLC 18350868.

- .

- JSTOR 1380307.

- ^ Kielan-Jaworowska Z, Hurum JH (2006). "Limb posture in early mammals: Sprawling or parasagittal" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 51 (3): 10237–10239.

- OCLC 5910695.

- S2CID 25806501.

- S2CID 8319185.

- ^ "Breast Development". Texas Children's Hospital. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- PMID 27666133.

- ^ PMID 20106856.

- S2CID 17272200.

- S2CID 4356708.

- S2CID 4314965.

- ^ S2CID 4334424.

- S2CID 206544776.

- PMID 28075073.

- PMID 27358361.

- ^ S2CID 4321956.

- OCLC 60007175.

- OCLC 874883911.

- PMID 22686855.

- S2CID 37750062.

- PMID 26957493.

- PMID 26020958.

- JSTOR 2453526.

- .

- ^ OCLC 940749490.

- ISBN 978-0-19-920878-4.

- OCLC 166505919.

- PMID 21729779.

- PMID 16587795.

- OCLC 213447727.

- OCLC 898069394.

- OCLC 940633137.

- ^ OCLC 945076700.

- ^ OCLC 124031907.

- ISBN 978-0-935848-47-2.

- ISBN 978-0-226-72490-4.

- .

- ^ S2CID 30816018.

- OCLC 437300511.

- ISBN 978-1-110-76857-8.

- ISBN 978-81-203-4107-4.

- ISBN 978-0-19-983012-1.

- ISBN 978-3-540-76838-8.

- PMID 11441026.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-03-910284-5.

- ISBN 978-1-42143-733-0.

- ^ Biological Reviews – Cambridge Journals

- ISBN 978-0-544-85993-7.

- ^ a b c Fitch WT (2006). "Production of Vocalizations in Mammals" (PDF). In Brown K (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 115–121.

- JSTOR 3504110.

- PMID 12363272.

- PMID 23155427.

- .

- ^ S2CID 9481486.

- S2CID 21168932.

- ^ Hilton Jr B (1996). "South Carolina Wildlife". Animal Colors. 43 (4). Hilton Pond Center: 10–15. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ S2CID 8268610.

- PMID 20353556.

- .

- PMID 23589881.

- PMID 18990666.

- S2CID 31722173.

- S2CID 13916535. Archived from the original(PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- S2CID 9849814.

- ISBN 978-4-431-56609-0.

- ISBN 978-0-226-87013-7.

- ISBN 978-0-7923-8336-9.

- ISBN 978-0-521-33792-2.

- S2CID 40632746.

- ISBN 978-1-11824-364-0. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-52024-406-1. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-4899-5988-1.

- ISBN 978-0-03-025034-7.

- ^ S2CID 205570021.

- S2CID 812974.

- PMID 18983263. Archived from the original(PDF) on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- OCLC 53476660.

- ISBN 978-81-219-2557-0.

- S2CID 25806501.

- ISBN 978-1-139-45742-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4214-2042-4.

- ISBN 978-0-226-44011-8.

- OCLC 47521441.

- .

- OCLC 35744403.

- ^ PMID 19896964.

- PMID 4526202.

- PMID 27874830.

- PMID 1465394.

- S2CID 19830165.

- PMID 7060140.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link - S2CID 23988416.

- OCLC 40576267.

- PMID 15861420.

- PMID 11171362.

- ^ Dhingra P (2004). "Comparative Bipedalism – How the Rest of the Animal Kingdom Walks on two legs". Anthropological Science. 131 (231).

- PMID 15198697.

- ^ .

- OCLC 33167785.

- ^ OCLC 11114191.

- S2CID 78090049.

- ^ Barba LA (October 2011). "Bats – the only flying mammals". Bio-Aerial Locomotion. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "Bats In Flight Reveal Unexpected Aerodynamics". ScienceDaily. 2007. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- S2CID 21295393.

- ^ "Bats save energy by drawing in wings on upstroke". ScienceDaily. 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- OCLC 191258477.

- PMID 21690408.

- ^ Damiani, R, 2003, Earliest evidence of cynodont burrowing, The Royal Society Publishing, Volume 270, Issue 1525

- S2CID 83519668.

- PMID 9707584.

- .

- doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.1991.tb00292.x. Archived from the original(PDF) on 29 August 2006.

- OCLC 27492815. Archived from the original(PDF) on 11 May 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-27057-2.

- ^ PMID 12517984.

- ^ OCLC 19511610.

- .

- S2CID 49732160. Archived from the original(PDF) on 4 August 2016.

- OCLC 42274422.

- ^ "Hippopotamus Hippopotamus amphibius". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 25 November 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ S2CID 53165940.

- S2CID 21374702.

- PMID 12028787.

- ISBN 978-0-12-373553-9.

- S2CID 86121405.

- PMID 9493408.

- ^ "Prairie dogs' language decoded by scientists". CBC News. 21 June 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Mayell H (3 March 2004). "Elephants Call Long-Distance After-Hours". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 5 March 2004. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- OCLC 54460090.

- S2CID 2809268. Archived from the original(PDF) on 25 February 2014.

- S2CID 83504795.

- .

- .

- .

- .

- OCLC 50143737.

- OCLC 26158593.

- PMID 26393325.

- ^ Speaksman JR (1996). "Energetics and the evolution of body size in small terrestrial mammals" (PDF). Symposia of the Zoological Society of London (69): 69–81. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ OCLC 46422124.

- ^ PMID 21672827.

- .

- doi:10.1890/02-0397.

- .

- ^ "Why Do Cats Eat Grass?". Pet MD. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- S2CID 22397415.

- S2CID 14675451.

- PMID 2740905.

- ISBN 978-3-642-02420-7.

- ^ Mayer, p. 59.

- PMID 35831501.

- ^ a b c d e Broom, p. 105.

- ^ Smith, p. 238.

- ^ "Cats' Tongues Employ Tricky Physics". 12 November 2010.

- ^ Smith, p. 237.

- ^ Mayer, p. 54.

- ^ "How do Giraffes Drink Water?". February 2016.

- PMID 24101631.

- OCLC 674694369.

- OCLC 2000769.

- S2CID 15216926.

- PMID 17488526.

- S2CID 27074107.

- S2CID 145295899.

- PMID 17075063.

- S2CID 85330986.

- S2CID 38985498.

- OCLC 30739453.

- OCLC 25874476.

- ^ OCLC 28180680.

- ^ S2CID 31124804.

- S2CID 880054.

- .

- ^ Hardy SB (2009). Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding. Boston: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 92–93.

- PMID 5283943.

- S2CID 13366732.

- PMID 16537121.

- S2CID 24927919. Archived from the original(PDF) on 25 April 2014.

- PMID 24023806.

- S2CID 4510393.

- ISBN 978-3-0348-7726-8.

- S2CID 21961356.

- PMID 26569400.

- .

- S2CID 53186523.

- .

- S2CID 25675086.

- PMID 28568154. Archived from the original(PDF) on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- S2CID 84780662.

- S2CID 25266746.

- OCLC 913709574.

- (PDF) from the original on 3 November 2023.

- ^ The Humane Society of the United States. "U.S. Pet Ownership Statistics". Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ USDA. "U.S. Rabbit Industry profile" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ McKie R (26 May 2013). "Prehistoric cave art in the Dordogne". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ Jones J (27 June 2014). "The top 10 animal portraits in art". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Deer Hunting in the United States: An Analysis of Hunter Demographics and Behavior Addendum to the 2001 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation Report 2001-6". Fishery and Wildlife Service (US). Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Shelton L (5 April 2014). "Recreational Hog Hunting Popularity Soaring". The Natchez Democrat. Grand View Outdoors. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-4403-3856-4. Chapters on hunting deer, wild hog (boar), rabbit, and squirrel.

- ^ "Horse racing". The Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 December 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- OCLC 9324926.

- .

- ^ Fowler KJ (26 March 2014). "Top 10 books about intelligent animals". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- OCLC 71285210.

- ^ "Books for Adults". Seal Sitters. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- .

- OCLC 665137673.

- ^ van Gulik RH. Hayagrīva: The Mantrayānic Aspect of Horse-cult in China and Japan. Brill Archive. p. 9.

- ^ Grainger R (24 June 2012). "Lion Depiction across Ancient and Modern Religions". ALERT. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- OCLC 35792200.

- PMID 23415592. Archived from the original(PDF) on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- PMID 18697943.

- ^ "Graphic detail Charts, maps and infographics. Counting chickens". The Economist. 27 July 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ "Breeds of Cattle at CATTLE TODAY". Cattle Today. Cattle-today.com. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ Lukefahr SD, Cheeke PR. "Rabbit project development strategies in subsistence farming systems". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- OCLC 57033325.

- OCLC 963977000.

- ^ Quiggle C (Fall 2000). "Alpaca: An Ancient Luxury". Interweave Knits: 74–76.

- ^ "Wild mammals make up only a few percent of the world's mammals". Our World in Data. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ "Genetics Research". Animal Health Trust. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ "Drug Development". Animal Research.info. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ "EU statistics show decline in animal research numbers". Speaking of Research. 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- . Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ "The supply and use of primates in the EU". European Biomedical Research Association. 1996. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012.

- S2CID 41368228.

- ^ Weatherall D, et al. (2006). The use of non-human primates in research (PDF) (Report). London: Academy of Medical Sciences. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2013.

- ^ Ritchie H, Roser M (15 April 2021). "Biodiversity". Our World in Data.

- ^ PMID 29784790.

- OCLC 226038028.

- OCLC 495479133.

- .

- OCLC 940879282.

- PMID 11344292.

- PMID 25691958.

- ^ Wilson A (2003). Australia's state of the forests report. p. 107.

- .

- OCLC 48794104.

- ^ S2CID 206555761.

- OCLC 876140621.

- PMID 25061199.

- PMID 16701402. Archived from the original(PDF) on 10 June 2010.

- OCLC 10301944.

- ^ Watts J (6 May 2019). "Human society under urgent threat from loss of Earth's natural life". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ McGrath M (6 May 2019). "Nature crisis: Humans 'threaten 1m species with extinction'". BBC. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ Main D (22 November 2013). "7 Iconic Animals Humans Are Driving to Extinction". Live Science.

- ^ Platt JR (25 October 2011). "Poachers Drive Javan Rhino to Extinction in Vietnam". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015.

- ^ Carrington D (8 December 2016). "Giraffes facing extinction after devastating decline, experts warn". The Guardian.

- PMID 28116351.

- ^ Fletcher M (31 January 2015). "Pangolins: why this cute prehistoric mammal is facing extinction". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ Greenfield P (9 September 2020). "Humans exploiting and destroying nature on unprecedented scale – report". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ McCarthy D (1 October 2020). "Terrifying wildlife losses show the extinction end game has begun – but it's not too late for change". The Independent. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- Science. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- PMID 27853564.

- S2CID 7771527.

- Science. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- PMID 26231772.

- JSTOR 1311860.

- OCLC 207259298.

- .

- ^ Gobush K. "Effects of Poaching on African elephants". Center For Conservation Biology. University of Washington. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- OCLC 31424005.

- OCLC 32201845.

- ^ "About IUCN". International Union for Conservation of Nature. 3 December 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- PMID 26601195.

- PMID 20880890.

- ISBN 978-1-4214-1718-9.

- . Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ OCLC 777948078.

- OCLC 455328678.

- As of this edit, this article uses content from "Anatomy and Physiology", which is licensed in a way that permits reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, but not under the GFDL. All relevant terms must be followed.

Further reading

- Brown WM (2001). "Natural selection of mammalian brain components". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 16 (9): 471–473. .

- McKenna MC, Bell SK (1997). Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level. New York: Columbia University Press. OCLC 37345734.[permanent dead link]

- Nowak RM (1999). Walker's mammals of the world (6th ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. OCLC 937619124.

- Simpson GG (1945). "The principles of classification and a classification of mammals". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 85: 1–350.

- Murphy WJ, Eizirik E, O'Brien SJ, Madsen O, Scally M, Douady CJ, et al. (December 2001). "Resolution of the early placental mammal radiation using Bayesian phylogenetics". Science. 294 (5550): 2348–2351. S2CID 34367609.

- Springer MS, Stanhope MJ, Madsen O, de Jong WW (August 2004). "Molecules consolidate the placental mammal tree" (PDF). Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 19 (8): 430–438. S2CID 1508898. Archived from the original(PDF) on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2005.

- Vaughan TA, Ryan JM, Capzaplewski NJ (2000). Mammalogy (4th ed.). Fort Worth, Texas: Saunders College Publishing. OCLC 42285340.

- Kriegs JO, Churakov G, Kiefmann M, Jordan U, Brosius J, Schmitz J (April 2006). "Retroposed elements as archives for the evolutionary history of placental mammals". PLOS Biology. 4 (4): e91. PMID 16515367.

- MacDonald DW, Norris S (2006). The Encyclopedia of Mammals (3rd ed.). London: Brown Reference Group. OCLC 74900519.

External links

- ASM Mammal Diversity Database

- Biodiversitymapping.org – All mammal orders in the world with distribution maps Archived 2016-09-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Paleocene Mammals Archived 3 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine, a site covering the rise of the mammals, paleocene-mammals.de

- Evolution of Mammals, a brief introduction to early mammals, enchantedlearning.com

- European Mammal Atlas EMMA from Societas Europaea Mammalogica, European-mammals.org

- Marine Mammals of the World – An overview of all marine mammals, including descriptions, both fully aquatic and semi-aquatic, noaa.gov

- Mammalogy.org Archived 1 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine The American Society of Mammalogists was established in 1919 for the purpose of promoting the study of mammals, and this website includes a mammal image library