Mandibular symphysis

| Mandibular symphysis | |

|---|---|

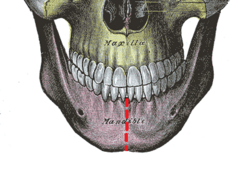

Anterior view of mandible, showing mandibular symphysis (red broken line) | |

Medial surface of the left half of the mandible, dis-articulated from the right side at the mandibular symphysis | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | symphysis mandibulae |

| TA98 | A02.1.15.004 |

| TA2 | 838 |

| FMA | 75779 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

In human anatomy, the

This ridge divides below and encloses a triangular eminence, the mental protuberance, the base of which is depressed in the center but raised on either side to form the mental tubercle. The lowest (most inferior) end of the mandibular symphysis — the point of the chin — is called the "menton".[2][3]

It serves as the origin for the

Other animals

Solitary mammalian carnivores that rely on a powerful canine bite to subdue their prey have a strong mandibular symphysis, while pack hunters delivering shallow bites have a weaker one.[4] When filter feeding, the baleen whales, of the suborder Mysticeti, can dynamically expand their oral cavity in order to accommodate enormous volumes of sea water. This is made possible thanks to its mandibular skull joints, especially the elastic mandibular symphysis which permits both dentaries to be rotated independently in two planes. This flexible jaw, which made the titanic body sizes of baleen whales possible, is not present in early whales and most likely evolved within Mysticeti.[5]

Many primitive proboscideans belonging to the group Elephantiformes have a greatly elongated mandibular symphysis. This was lost in many later groups, including modern elephants.[6]

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 172 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 172 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

Notes

- ISSN 0002-9483. Retrieved 2023-12-10.

- ^ "Menton". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ISBN 9789350903247.

- .

- ^ Fitzgerald 2012

- .

Sources

- Fitzgerald, Erich M. G. (2012). "Archaeocete-like jaws in a baleen whale". Biol. Lett. 8 (1): 94–96. PMID 21849306.