Mangrove forest

ebb tide |

|---|

| Coastal habitats |

| Ocean surface |

|

| Open ocean |

| Sea floor |

Mangrove forests, also called mangrove swamps, mangrove thickets or mangals, are productive

Many mangrove forests can be recognised by their dense tangle of prop roots that make the trees appear to be standing on stilts above the water. This tangle of roots allows the trees to handle the daily rise and fall of tides, as most mangroves get flooded at least twice per day. The roots slow the movement of tidal waters, causing sediments to settle out of the water and build up the muddy bottom. Mangrove forests stabilise the coastline, reducing erosion from storm surges, currents, waves, and tides. The intricate root system of mangroves also makes these forests attractive to fish and other organisms seeking food and shelter from predators.[3]

Mangrove forests live at the interface between the land, the ocean, and the atmosphere, and are centres for the flow of energy and matter between these systems. They have attracted much research interest because of the various ecological functions of the mangrove ecosystems, including runoff and flood prevention, storage and recycling of nutrients and wastes, cultivation and energy conversion.

Overview

| External videos | |

|---|---|

– Mangrove Action Project |

There are about 80 different species of mangrove trees. All of these trees grow in areas with low-oxygen soil, where slow-moving waters allow fine sediments to accumulate. Mangrove forests grow only at tropical and subtropical latitudes near the equator because they cannot withstand freezing temperatures.[7] Many mangrove forests can be recognised by their dense tangle of prop roots that make the trees appear to be standing on stilts above the water. This tangle of roots allows the trees to handle the daily rise and fall of tides, which means that most mangroves get flooded at least twice per day. The roots slow the movement of tidal waters, causing sediments to settle out of the water and build up the muddy bottom. Mangrove forests stabilise the coastline, reducing erosion from storm surges, currents, waves, and tides. The intricate root system of mangroves makes these forests attractive to fishes and other organisms seeking food and shelter from predators.[8]

The main contribution of mangroves to the larger ecosystem comes from litter fall from the trees, which is then decomposed by primary consumers. Bacteria and protozoans colonise the plant litter and break it down chemically into organic compounds, minerals, carbon dioxide, and nitrogenous wastes.[8] The intertidal existence to which these trees are adapted represents the major limitation to the number of species able to thrive in their habitat. High tide brings in salt water, and when the tide recedes, solar evaporation of the seawater in the soil leads to further increases in salinity. The return of tide can flush out these soils, bringing them back to salinity levels comparable to that of seawater.[9][10] At low tide, organisms are exposed to increases in temperature and reduced moisture before being then cooled and flooded by the tide. Thus, for a plant to survive in this environment, it must tolerate broad ranges of salinity, temperature, and moisture, as well as several other key environmental factors—thus only a select few species make up the mangrove tree community.[10][9]

A mangrove swamp typically features only a small number of tree species. It is not uncommon for a mangrove forest in the Caribbean to feature only three or four tree species. For comparison, a tropical rainforest biome may contain thousands of tree species, but this is not to say mangrove forests lack diversity. Though the trees are few in species, the ecosystem that these trees create provides a habitat for a great variety of other species, including as many as 174 species of marine megafauna.[11]

Mangrove plants require a number of physiological adaptations to overcome the problems of low environmental oxygen levels, high salinity, and frequent tidal flooding. Each species has its own solutions to these problems; this may be the primary reason why, on some shorelines, mangrove tree species show distinct zonation. Small environmental variations within a mangal may lead to greatly differing methods for coping with the environment. Therefore, the mix of species is partly determined by the tolerances of individual species to physical conditions, such as tidal flooding and salinity, but may also be influenced by other factors, such as crabs preying on plant seedlings.[13]

Once established, mangrove roots provide an

Mangrove swamps protect coastal areas from erosion, storm surge (especially during tropical cyclones), and tsunamis.[15][16][17] They limit high-energy wave erosion mainly during events such as storm surges and tsunamis.[18] The mangroves' massive root systems are efficient at dissipating wave energy.[19] Likewise, they slow down tidal water enough so that its sediment is deposited as the tide comes in, leaving all except fine particles when the tide ebbs.[20] In this way, mangroves build their environments.[15] Because of the uniqueness of mangrove ecosystems and the protection against erosion they provide, they are often the object of conservation programs,[10] including national biodiversity action plans.[16]

Distribution

Distribution of delta, estuary, lagoon and open coast mangrove types

in (i) South Asia, (ii) Southeast Asia and (iii) East Asia [22]

Bar charts show percentage change in area between 1996 and 2016

Worldwide there are about 80 described species of mangroves that live along marine coasts. About 60 of these species are true mangroves which live only in the intertidal zone between high and low tides.[23] "Mangroves once covered three-quarters of the world's tropical coastlines, with Southeast Asia hosting the greatest diversity. Only 12 species live in the Americas. Mangroves range in size from small bushes to the 60-meter giants found in Ecuador. Within a given mangrove forest, different species occupy distinct niches. Those that can handle tidal soakings grow in the open sea, in sheltered bays, and on fringe islands. Trees adapted to drier, less salty soil can be found farther from the shoreline. Some mangroves flourish along riverbanks far inland, as long as the freshwater current is met by ocean tides."[23]

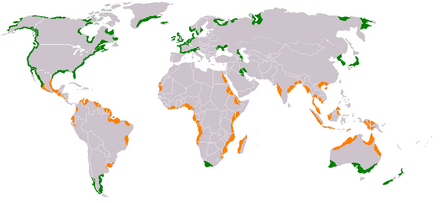

orange: mangroves dominate green: salt marshes dominate

Mangroves can be found in 118 countries and territories in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world.[21] The largest percentage of mangroves is found between the 5° N and 5° S latitudes. Approximately 75% of world's mangroves are found in just 15 countries.[21] Estimates of mangrove area based on remote sensing and global data tend to be lower than estimates based on literature and surveys for comparable periods.[9]

In 2018, the Global Mangrove Watch Initiative released a global baseline based on remote sensing and global data for 2010.[21] They estimated the total mangrove forest area of the world as of 2010 at 137,600 km2 (53,100 sq mi), spanning 118 countries and territories.[9][24] Following the conventions for identifying geographic regions from the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, researchers reported that Asia has the largest share (38.7%) of the world's mangroves, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (20.3%), Africa (20.0%), Oceania (11.9%), and Northern America (8.4%).[24]

Sundarbans

The largest mangrove forest in the world is in the

The Sundarbans is intersected by a complex network of tidal waterways, mudflats and small islands of salt-tolerant mangrove forests. The interconnected network of waterways makes almost every portion of the forest accessible by boat. The area is known as an important habitat for the endangered Bengal tiger, as well as numerous fauna including species of birds, spotted deer, crocodiles and snakes. The fertile soils of the delta have been subject to intensive human use for centuries, and the ecoregion has been mostly converted to intensive agriculture, with few enclaves of forest remaining.[26] Additionally, the Sundarbans serves a crucial function as a protective barrier for millions of inhabitants against floods that result from cyclones.

Four protected areas in the Sundarbans are listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[27] Despite these protections, the Indian Sundarbans were assessed as endangered in 2020 under the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems framework.[28] There is a consistent pattern of depleted biodiversity or loss of species and the ecological quality of the forest is declining.[29]

-

Map of the Sundarbans

-

Bengal tiger in the Sunderbans

-

Channel in low tide

Ecosystem

The unique ecosystem found in the intricate mesh of mangrove roots offers a quiet marine habitat for young organisms.[30] In areas where roots are permanently submerged, the organisms they host include algae, barnacles, oysters, sponges, and bryozoa, which all require a hard surface for anchoring while they filter-feed. Shrimp and mud lobsters use the muddy bottoms as their home.[31] Mangrove crabs eat the mangrove leaves, adding nutrients to the mangal mud for other bottom feeders.[32] In at least some cases, the export of carbon fixed in mangroves is important in coastal food webs.[33] Mangrove plantations host several commercially important species of fish and crustaceans.[34]

In

Mangrove forests are an important part of the cycling and storage of carbon in tropical coastal ecosystems.[35] Knowing this, scientists seek to reconstruct the environment and investigate changes to the coastal ecosystem over thousands of years using sediment cores.[36] However, an additional complication is the imported marine organic matter that also gets deposited in the sediment through the tidal flushing of mangrove forests.[35]

Mangrove forests can decay into

Mangroves are an important source of blue carbon. Globally, mangroves stored 4.19 Gt (9.2×1012 lb) of carbon in 2012.[37] Two percent of global mangrove carbon was lost between 2000 and 2012, equivalent to a maximum potential of 0.316996250 Gt (6.9885710×1011 lb) of CO2 emissions.[37] Globally, mangroves have been shown to provide measurable economic protections to coastal communities affected by tropical storms.[38]

Biodiversity

Birds

Heterogeneity in landscape ecology is a measure of how different parts of a landscape are from one another. It can manifest in an ecosystem from the abiotic or biotic characteristics of the environment. For example, coastal mangrove forests are located at the land-sea interface, so their functioning is influenced by abiotic factors such as tides, as well as biotic factors such as the extent and configuration of adjacent vegetation.[39] For forest birds, tidal inundation means that the availability of many mangrove resources fluctuates daily, suggesting foraging flexibility is likely to be important. Mangroves also offer estuarine prey items, such as mudskippers and crabs, that are not found in terrestrial forest types. Further, mangroves are often situated in a complex mosaic of adjacent vegetation types such as grasslands, saltmarshes, and woodlands, and this can mean that flexibility in foraging strategy and choice of foraging habitat may be advantageous for highly mobile forest birds.[39] Relative to other forest types, mangroves support few bird species that are obligate habitat (mangrove) specialists and instead host many species with generalised foraging niches.[40][39]

-

Mangrove forests host many bird species with generalised foraging niches

-

Mangrove kingfishers are found particularly in mangrove zones

-

Brown pelicans fish and nest in mangrove forests

-

Little blue heron. The water is reflecting green mangrove trees.

-

Three great egrets fishing along a mangrove shore

-

Pelicans and cormorants high in the mangrove trees

- Bird sanctuaries

Mangrove forests are home and sanctuaries for many of aquatic bird species, including:

- Pulicat Lake Bird Sanctuary

- Mangalavanam Bird Sanctuary

- Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary

- Pichavaram

- Coringa Wildlife Sanctuary

- Sundarbans National Park

Fish

The intricate root system of mangrove forests makes them attractive to adult fish seeking food and juvenile fish seeking shelter.[3]

-

Mangrove jack

-

Mangrove snapper swimming among mangrove roots

-

Old World silversides schooling among mangrove roots

-

Barracuda lurks among mangrove root

-

Yellow seahorsesbreed and give birth in Asia's flooded mangrove forests. Tangled roots and submerged branches offer shadowy shelter to pregnant dads and their offspring

-

Mudskippers can be found in mangrove swamps

-

Mangrove whipray

Mangrove crab holobiont

Mangrove forests are among the more productive and diverse ecosystems on the planet, despite limited nitrogen availability. Under such conditions, animal-microbe associations (holobionts) are often key to ecosystem functioning. An example is the role of fiddler crabs and their carapace-associated microbial biofilm as hotspots of microbial nitrogen transformations and sources of nitrogen within the mangrove ecosystem.[41]

Among coastal ecosystems, mangrove forests are of great importance as they account for three quarters of the tropical coastline and provide different ecosystem services.

Bioturbation by macrofauna affect nitrogen availability and multiple nitrogen related microbial processes through sediment reworking, burrow construction and bioirrigation, feeding and excretion.[50] Macrofauna mix old and fresh organic matter, extend oxic–anoxic sediment interfaces, increase the availability of energy-yielding electron acceptors and increase nitrogen turnover via direct excretion.[51][52] Thus, macrofauna may alleviate nitrogen limitation by priming the remineralisation of refractory nitrogen (that is, the nitrogen that can't be biologically decomposed), reducing plant-microbe competition.[53][54] Such activity ultimately promotes nitrogen recycling, plant assimilation and high nitrogen retention, as well as favours its loss by stimulating coupled nitrification and denitrification.[55][41]

Dry weight of crab biofilm and mean dry weight of incubated crab expressed as µmol nitrogen per crab per day

Mangrove sediments are highly bioturbated by decapods such as crabs.[58] Crab populations continuously rework sediment by constructing burrows, creating new niches, transporting or selectively grazing on sediment microbial communities.[58][59][60][61] In addition, crabs can affect organic matter turnover by assimilating leaves and producing finely fragmented faeces, or by carrying them into their burrows.[62][63] Therefore, crabs are considered important ecosystem engineers shaping biogeochemical processes in intertidal muddy banks of mangroves.[64][65] In contrast to burrowing polychaetes or amphipods, the abundant Ocipodid crabs, mainly represented by fiddler crabs, do not permanently ventilate their burrows. These crabs may temporarily leave their burrows for surface activities,[61] or otherwise plug their burrow entrance during tidal inundation in order to trap air.[66] A recent study showed that these crabs can be associated with a diverse microbial community, either on their carapace or in their gut.[60][41]

The exoskeleton of living animals, such as shells or carapaces, offers a habitat for microbial biofilms which are actively involved in different N-cycling pathways such as nitrification, denitrification and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA).[67][68][69][70][71][72] Colonizing the carapace of crabs may be advantageous for specific bacteria, because of host activities such as respiration, excretion, feeding and horizontal and vertical migrations.[73] However, the ecological interactions between fiddler crabs and bacteria, their regulation and significance as well as their implications at scales spanning from the single individual to the ecosystem are not well understood.[60][74][41]

-

Artist impression of small blue soldier crabs marching across a mangrove flat [75]

-

Mangrove crab, possibly Neosarmatium asiaticum

-

Mangrove tree crab, Aratus pisonii

Biogeochemistry

Carbon cycle

Mangrove forests are amongst the world's most productive marine ecosystems,

The out-welling hypothesis argues that export of locally derived POC and DOC is an important ecosystem function of mangroves, which drives detrital based

In the 1990s, global estimates could account for 48% of the total global mangrove

Nitrogen assimilation

Mangrove forests and coastal marshes are typically considered N-limited ecosystems because of their high primary production.[94][95] Therefore, mangrove plants are highly efficient at utilising soil nitrogen, making them an important sink for excess nitrogen from upstream.[96][46] However, different mangrove species may still utilise nitrogen at different efficiencies,[97] even though they share similar nitrogen pathways (see diagram on right). Reported nitrogen assimilation rates in mangrove plants ranged from 2 to 8 μmol g−1 h−1 under ambient nitrogen conditions,[98] and 19 to 251 μmol g−1 h−1 when the nitrogen supply was unlimited.[99][92]

In addition to species variation, different environmental conditions can also affect the nitrogen assimilation rates in mangrove plants. Because

Exploitation and conservation

Adequate data is only available for about half of the global area of mangroves. However, of those areas for which data has been collected, it appears that 35% of the mangroves have been destroyed.[102] Since the 1980s, around 2% of mangrove area is estimated to be lost each year.[103] Assessments of global variation in mangrove loss indicates that national regulatory quality mediates how different drivers and pressures influence loss rates.[104]

Shrimp farming causes approximately a quarter of the destruction of mangrove forests.[105][106] Likewise, the 2010 update of the World Mangrove Atlas indicated that approximately one fifth of the world's mangrove ecosystems have been lost since 1980,[107] although this rapid loss rate appears to have decreased since 2000 with global losses estimated at between 0.16% and 0.39% annually between 2000 and 2012.[108] Despite global loss rates decreasing since 2000, Southeast Asia remains an area of concern with loss rates between 3.6% and 8.1% between 2000 and 2012.[108] By far the most damaging form of shrimp farming is when a closed ponds system (non-integrated multi-trophic aquaculture) is used, as these require destruction of a large part of the mangrove, and use antibiotics and disinfectants to suppress diseases that occur in this system, and which may also leak into the surrounding environment. Far less damage occurs when integrated mangrove-shrimp aquaculture is used, as this is connected to the sea and subjected to the tides, and less diseases occur, and as far less mangrove is destroyed for it.[109]

Grassroots efforts to protect mangroves from development and from citizens cutting down the mangroves for

- In Thailand, community management has been effective in restoring damaged mangroves.[112] Also, production of mangrove honey is practiced, as a way to generate sustainable income for nearby people, keeping them from destroying the mangrove and generate a short-term revenue.[113][114]

- In Madagascar, honey is also produced in mangroves as a source of (non-destructive) income generation. In addition, silk pods from endemic silkworm species are also collected in the Madagascar mangroves for wild silk production.[115][111]

- In the Bahamas, for example, active efforts to save mangroves are occurring on the islands of Bimini and Great Guana Cay.

- In Trinidad and Tobago as well, efforts are underway to protect a mangrove threatened by the construction of a steel mill and a port.[citation needed]

- Within northern Ecuador, mangrove regrowth is reported in almost all estuaries and stems primarily from local actors responding to earlier periods of deforestation in the Esmeraldas region.[116]

Mangroves have been reported to be able to help buffer against tsunami, cyclones, and other storms, and as such may be considered a flagship system for

Ocean deoxygenation

Compared to seagrass meadows and coral reefs, hypoxia is more common on a regular basis in mangrove ecosystems, through ocean deoxygenation is compounding the negative effects by anthropogenic nutrient inputs and land use modification.[118]

Like seagrass, mangrove trees transport oxygen to roots of

Due to these frequent hypoxic conditions, the water does not provide habitats to fish. When exposed to extreme hypoxia, ecosystem function can completely collapse. Extreme deoxygenation will affect the local fish populations, which are an essential food source. The environmental costs of shrimp farms in the mangrove forests grossly outweigh the economic benefits of them. Cessation of shrimp production and restoration of these areas reduce eutrophication and anthropogenic hypoxia.[118]

Reforestation

In some areas, mangrove

| External videos | |

|---|---|

– Mangrove Action Project |

The Manzanar Mangrove Initiative is an ongoing experiment in Arkiko, Eritrea, part of the Manzanar Project founded by Gordon H. Sato, establishing new mangrove plantations on the coastal mudflats. Initial plantings failed, but observation of the areas where mangroves did survive by themselves led to the conclusion that nutrients in water flow from inland were important to the health of the mangroves. Trials with the Eritrean Ministry of Fisheries followed, and a planting system was designed to provide the nitrogen, phosphorus, and iron missing from seawater.[120][121]

The propagules are planted inside a reused galvanized steel can with the bottom knocked out; a small piece of iron and a pierced plastic bag with fertilizer containing nitrogen and phosphorus are buried with the propagule. As of 2007[update], after six years of planting, 700,000 mangroves are growing; providing stock feed for sheep and habitat for oysters, crabs, other bivalves, and fish.[120][121]

Another method of restoring mangroves is by using

Seventy percent of mangrove forests have been lost in Java, Indonesia. Mangroves formerly protected the island's coastal land from flooding and erosion.[123] Wetlands International, an NGC based in the Netherlands, in collaboration with nine villages in Demak where lands and homes had been flooded, began reviving mangrove forests in Java. Wetlands International introduced the idea of developing tropical versions of techniques traditionally used by the Dutch to catch sediment in North Sea coastal salt marshes.[123] Originally, the villagers constructed a sea barrier by hammering two rows of vertical bamboo poles into the seabed and filling the gaps with brushwood held in place with netting. Later the bamboo was replaced by PVC pipes filled with concrete. As sediment gets deposited around the brushwood, it serves to catch floating mangrove seeds and provide them with a stable base to germinate, take root and regrow. This creates a green belt of protection around the islands. As the mangroves mature, more sediment is held in the catchment area; the process is repeated until a mangrove forest has been restored. Eventually the protective structures will not be needed.[123] By late 2018, 16 km (9.9 mi) of brushwood barriers along the coastline had been completed.[123]

A concern over reforestation is that although it supports increases in mangrove area it may actually result in a decrease in global mangrove functionality and poor restoration processes may result in longer term depletion of the mangrove resource.[124]

National and international studies

In terms of local and national studies of mangrove loss, the case of Belize's mangroves is illustrative in its contrast to the global picture. A recent, satellite-based study[125]—funded by the World Wildlife Fund and conducted by the Water Center for the Humid Tropics of Latin America and the Caribbean (CATHALAC)—indicates Belize's mangrove cover declined by a mere 2% over a 30-year period. The study was born out of the need to verify the popular conception that mangrove clearing in Belize was rampant.[126]

Instead, the assessment showed, between 1980 and 2010, under 16 km2 (6.2 sq mi) of mangroves had been cleared, although clearing of mangroves near Belize's main coastal settlements (e.g. Belize City and San Pedro) was relatively high. The rate of loss of Belize's mangroves—at 0.07% per year between 1980 and 2010—was much lower than Belize's overall rate of forest clearing (0.6% per year in the same period).[127] These findings can also be interpreted to indicate Belize's mangrove regulations (under the nation's)[128] have largely been effective. Nevertheless, the need to protect Belize's mangroves is imperative, as a 2009 study by the World Resources Institute (WRI) indicates the ecosystems contribute US$174 to US$249 million per year to Belize's national economy.[129]

From 1990, in Tanzania, Adelaida K. Semesi led aresearch programme which resulted in Tanzania being one of the first countries to have an environemntal management plan for mangroves.[130] Nicknamed "mama mikoko" ("mama mangroves" in Swahili),[131][132] Semesi also was a Council Member for the International Society for Mangrove Ecosystems.[133]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In May 2019, ORNL DAAC News announced that NASA's Carbon Monitoring System (CMS), using new satellite-based maps of global mangrove forests across 116 countries, had created a new dataset to characterize the "distribution, biomass, and canopy height of mangrove-forested wetlands".[134][135] Mangrove forests move carbon dioxide "from the atmosphere into long-term storage" in greater quantities than other forests, making them "among the planet's best carbon scrubbers" according to a NASA-led study.[135][136]

See also

- Ecological values of mangroves

- Mangrove restoration

- Mangrove tree distribution

- Freshwater swamp forest

References

- .

- .

- ^ a b c What is a mangrove forest? National Ocean Service, NOAA. Updated: 25 March 2021. Retrieved: 4 October 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ISBN 9789001355944.

- S2CID 4983675.

- S2CID 52917236.

- ISSN 0304-3770.

- ^ a b Mangroves are trees and shrubs that have adapted to life in a saltwater environment National Marine Sanctuaries, NOAA. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ .

- ^ . Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- S2CID 164219103.

- PMID 32401792..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - PMID 29448932.

- CiteSeerX 10.1.1.961.9649.

- ^ S2CID 35322400.

- ^ S2CID 31945341.

- .

- S2CID 8772526.

- S2CID 122572658.

- S2CID 126945589.

- ^ . Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- PMID 32887898..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - ^ a b What's a Mangrove? And How Does It Work? American Museum of Natural History. Accessed 8 November 2021.

- ^ .

- ^ Pani, D. R.; Sarangi, S. K.; Subudhi, H. N.; Misra, R. C.; Bhandari, D. C. (2013). "Exploration, evaluation and conservation of salt tolerant rice genetic resources from Sundarbans region of West Bengal" (PDF). Journal of the Indian Society of Coastal Agricultural Research. 30 (1): 45–53.

- S2CID 130056584.

- .

- S2CID 222206165. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2021-10-15. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- PMID 20699005.

- PMID 24391259.

- ^ Encarta Encyclopedia 2005. "Seashore", by Heidi Nepf.

- S2CID 23407273.

- S2CID 3957868.

- ISBN 978-1-315-34177-4.

- ^ .

- .

- ^ S2CID 89785740.

- PMID 31160457.

- ^ PMID 30439959..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - PMID 30439959.

- ^ PMID 32811860..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - S2CID 52904699.

- ISBN 9780120261406.

- ^ S2CID 128922131.

- .

- ^ PMID 20566581.

- S2CID 128709551.

- S2CID 91314553.

- PMID 637550.

- .

- S2CID 94773926.

- .

- PMID 22533682.

- PMID 21265795.

- S2CID 89783098.

- ISBN 981-04-1308-4.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Ria Tan (2001). "Mud Lobster Thalassina anomala". Archived from the original on 2007-08-27.

- ^ .

- PMID 30842580.

- ^ PMID 29362507.

- ^ .

- .

- S2CID 88582703.

- .

- PMID 26525137.

- S2CID 7366251.

- PMID 28934286.

- PMID 27567196.

- S2CID 45429253.

- PMID 22830624.

- S2CID 198261071.

- PMID 30060193.

- PMID 22936927.

- PMID 26102286.

- ^ Soldier Crab Australian Museum. Updated: 15 December 2020.

- ^ S2CID 224810608..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - ^ S2CID 42641476.

- ^ PMID 24405426.

- JSTOR 2388158.

- ^ S2CID 86841519.

- ^ Odum, E.P. (1968) "A research challenge: evaluating the productivity of coastal and estuarine water". In: Proceedings of the second sea grant conference", pages 63-64. University of Rhode Island.

- ^ Odum, W.E. and Heald, E.J. (1972) ""Trophic analyses of an estuarine mangrove community". Bulletin of Marine Science, 22(3): 671-738.

- S2CID 28803158.

- S2CID 33556308.

- S2CID 128922131.

- S2CID 3957868.

- ISBN 978-3-319-62204-0.

- S2CID 3901928.

- S2CID 587963.

- .

- OCLC 928883552.

- ^ doi:10.3390/f11050492.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - S2CID 91613293.

- S2CID 42854661.

- ISSN 1051-0761.

- PMID 25499182.

- .

- ^ Datta, R.; Datta, B.K. (1999 ) "Desiccation induced nitrate and ammonium uptake in the red alga Catenella repens (Rhodophyta, Gigartinales)". Indian J. Geo Mar. Sci., 28: 458–460.

- ^ .

- S2CID 20302042.

- S2CID 40743147.

- ISBN 1-59726-040-1

- .

- S2CID 219750253.

- ISBN 0-471-38914-5

- .

- ^ "2010a. ""World Atlas of Mangroves" Highlights the Importance of and Threats to Mangroves: Mangroves among World's Most Valuable Ecosystems." Press release. Arlington, Virginia". The Nature Conservancy. Archived from the original on 2010-07-17. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- ^ S2CID 55999275.

- ^ "The Secret Life of Mangroves - Television - Distribution - ZED". www.zed.fr.

- ^ Charcoal is used as a cheap source of energy in developing countries for cooking purposes

- ^ a b "The Secret Life of Mangroves - Television - Distribution - ZED". www.zed.fr. Archived from the original on 2022-04-06. Retrieved 2021-11-09.

- ^ "Thailand – Trang Province – Taking Back the Mangroves with Community Management | The EcoTipping Points Project". Ecotippingpoints.org. Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- ^ "Bees: An income generator and mangrove conservation tool for a community in Thailand". IUCN. December 14, 2016.

- ^ "Harvesting honey for mangrove resilience in the Tsiribihina delta". The Mangrove Alliance. February 5, 2018.

- ^ "Madagascar: What's good for the forest is good for the native silk industry". Mongabay Environmental News. August 16, 2019.

- ^ Hamilton, S. & S. Collins (2013) Las respuestas a los medios de subsistencia deforestación de los manglares en las provincias del norte de Ecuador. Bosque 34:2

- ^ "Tree News, Spring/Summer 2005, Publisher Felix Press". Treecouncil.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- ^ a b c Laffoley, D. & Baxter, J.M. (eds.) (2019). Ocean deoxygenation: Everyone's problem - Causes, impacts, consequences and solutions. IUCN, Switzerland.

- ^ "2010a. ""World Atlas of Mangroves" Highlights the Importance of and Threats to Mangroves: Mangroves among World's Most Valuable Ecosystems." Press release. Arlington, Virginia". The Nature Conservancy. Archived from the original on 2010-07-17. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- ^ a b Warne, Kennedy (February 2007). "Mangroves: Forests of the Tide". National Geographic. Tim Laman, photographer. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ S2CID 45705546.

- ^ Guest, Peter (April 28, 2019). "Tropical forests are dying. Seed-slinging drones can save them". WIRED. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d Pearce, Fred (May 2, 2019). "On Java's Coast, A Natural Approach to Holding Back the Waters". Yale E360. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- S2CID 139106235.

- ^ Cherrington EA, Hernandez BE, Trejos NA, Smith OA, Anderson ER, Flores AI, Garcia BC (2010). Identification of Threatened and Resilient Mangroves in the Belize Barrier Reef System (PDF). Water Center for the Humid Tropics of Latin America and the Caribbean (CATHALAC) / Regional Visualization & Monitoring System (SERVIR) (Report). Technical report to the World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 31, 2013.

- ^ "Pelican_Cays_Review" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- ^ "Cherrington, E.A., Ek, E., Cho, P., Howell, B.F., Hernandez, B.E., Anderson, E.R., Flores, A.I., Garcia, B.C., Sempris, E., and D.E. Irwin. 2010. "Forest Cover and Deforestation in Belize: 1980–2010." Water Center for the Humid Tropics of Latin America and the Caribbean. Panama City, Panama. 42 pp" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 29, 2013.

- ^ "Government of Belize (GOB). 2003. "Forests Act Subsidiary Laws." Chapter 213 in: Substantive Laws of Belize. Revised Edition 2003. Government Printer: Belmopan, Belize. 137 pp" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2012.

- ^ Cooper, E.; Burke, L.; Bood, N. (2009). "Coastal Capital: Belize. The Economic Contribution of Belize's Coral Reefs and Mangroves" (PDF). Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

- ^ "Adelaida Kleti Semesi 1951-2001" (PDF). Mangroves (24). International Society for Mangrove Ecosystems. July 2001.

- ISBN 978-1-5275-9157-8.

- ^ "A Tribute to Adelaida K. Semesi" (PDF). WIOMSA Newsbrief. 6 (1). March 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-11-22.

- ^ "Adelaida Kleti Semesi 1951-2001" (PDF). Mangroves (24). International Society for Mangrove Ecosystems. July 2001.

- ^ "Mapping Global Mangrove Forests", ORNL DAAC News, May 6, 2019, retrieved May 15, 2019

- ^ a b Rasmussen, Carol; Carlowicz, Mike (February 25, 2019), New Satellite-Based Maps of Mangrove Heights (Text.Article), retrieved May 15, 2019

- S2CID 134827807.

External links

Media related to Mangrove forests at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mangrove forests at Wikimedia Commons