Manipur (princely state)

Manipur Kingdom Meitei: Meetei Leipak | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1110–1949 | |||||||||||

Manipuri ) | |||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Foundation of the Kangleipak Kingdom | 1110 | ||||||||||

| 1824 | |||||||||||

• Princely state of India | 1891 | ||||||||||

• Accession to the Indian Union | 1947 | ||||||||||

• Merged into the Indian Union | 1949 | ||||||||||

Population | |||||||||||

• 1941 | 512,069 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | India Myanmar | ||||||||||

The Manipur Kingdom[1][2][3][4]

was an ancient kingdom at the India–Burma frontier.

Kangleipak State

The early history of Manipur is composed of mythical narratives . The location of the

Manipur State

In 1714, King

British protectorate

Following the

At the death of Gambhir Singh, his son

After a thwarted attempt on his life, Nara Singh took power and held the throne until his death in 1850. His brother Devendra Singh was given the title of Raja by the British, but he was unpopular. After only three months, the rightful heir Chandrakirti Singh invaded Manipur and rose to the throne. Numerous members of the royal family tried to overthrow Chandrakirti Singh, but none of the rebellions was successful. In 1879, when British Deputy Commissioner G.H. Damant was killed by an Angami Naga party, the king of Manipur assisted the British by sending troops to neighbouring Kohima. Following this service to the crown, Chandrakirti Singh was rewarded with the Order of the Star of India.

After Maharaja Chandrakriti's death in 1886 his son

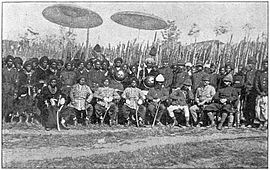

The 'Manipur Expedition'

The British decided to recognise Kulachandra Singh as Raja, and to send a military expedition of 400 men to Manipur to punish Senapati Tikendrajit Singh as the main person responsible for the unrest and the dynastic disturbances. This action and the violent events that followed are known in British annals as the 'Manipur Expedition, 1891',[22] while in Manipur they are known as the 'Anglo-Manipur War of 1891'.

The British attempt to remove Tikendrajit from his position as military commander (Senapati) and arrest him on 24 March 1891 caused a great stir. The British Residency in Imphal was attacked and the Chief Commissioner for Assam

Princely state under British Raj

The child ruler Churachand belonged to a side branch of the Manipur royal family, so that all the main contenders to the throne were bypassed. While he was a minor the affairs of state were administered by the British

Between March 1944 and July 1944 part of Manipur and the Naga Hills District of Assam Province were occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army. The capital Imphal was shelled on 10 May 1944.[26][verification needed]

Twilight and end of the princely state

On 14 August 1947, with the lapse of paramountcy of the British Crown, Manipur became briefly "independent" in the sense that it was free of control from the Governor of Assam, which may be regarded as reversion to political autonomy that existed before 1891.[27][28][29] However, the Maharaja had signed the Instrument of Accession on 11 August 1947, ceding the three subjects of defence, external affairs and communication to the Union of India.[27][30][31][32][33] A 'Manipur State Constitution Act 1947' was enacted, giving the state its own constitution, although this did not become known in other parts of India owing to the relative isolation of the kingdom.[29] The Government of India did not recognize the Constitution.[34]

On 21 September 1949, the Maharaja was coerced to sign a Merger Agreement with the Union of India, to take effect on 15 October the same year.

Unhappy with the central rule, Rishang Keishing began a movement for representative government in Manipur in 1954. The Indian home minister, however, declared that the time was not yet ripe for the creation of representative assemblies in Part C States such as Manipur and Tripura, stating that they were located in strategic border areas of India, that the people were politically backward and that the administration in those states was still weak.[36] However, it was given a substantial measure of local self-government under the Territorial Councils Act of 1956, a legislative body and council of ministers in 1963, and full statehood in 1972.[37]

Rulers

The rulers of Manipur state were entitled to an 11-gun salute by the British authorities. The present dynasty began in 1714.[38]

- 1709–1754 Gharib Nawaz(Pamheiba) (d. 1754)

- 1754–1756 Bharat Shah(Chitsai)

- 1756–1764 Guru Sham(Gaurisiam) (d. 1764)

- 1764–1798 Jai Singh (Bhagya Chandra)

- 1798–1801 Rohinchandra (Harshachandra Singh) (d. 1801)

- 1801–1806 Maduchandra Singh (d. 1806)

- 1806–1812 Charajit Singh(d. 1812)

- 1812–1819 Marjit Singh (d. 1824)

Rajas under Burmese rule

There were two feudatory kings during the time of the Burmese invasions.

- 1819–1823 Shubol

- 1823–1825 Pitambara Singh

Rajas under British protection

- 26 Jun 1825 – 9 January 1834 Gambhir Singh(d. 1834)

- 1834–1844 Nara Singh – Regent (d. 1850)

- 1844 – 10 April 1850 Nara Singh (s.a.)

- 1850 (3 months) Devendra Singh (d. 1871)

- 1850 – May 1886 Chandrakirti Singh(s.a.) (b. 1831 – d. 1886) (from 18 February 1880, Sir Chandrakirti Singh)

- 1886 – 24 September 1890 Surachandra Singh(d. 1891)

- 24 Sep 1890 – 19 April 1891 Kulachandra Singh (b. 18.. – d. 1934)

Rulers of the princely state under British Raj

- 19 Apr 1891 – 18 September 1891 Interregnum

- 18 Sep 1891 – September 1941 Churachandra Singh(b. 1885 – d. 1941, titled "Maharaja" in 1918, knighted 1934)

- Sep 1941 – 15 October 1949 Bodhchandra Singh (b. 1909 – d. 1955)

British Political Agents

The

- 1835–1844 George Gordon

- 1844–1863 William McCulloch (1st time)[40][a]

- 1863–1865 Dillon

- 1865–1867 William McCulloch (2nd time) (s.a.)

- 1867–1875 Robert Brown[b]

- 1875–1877 Guybon Henry Damant (acting)

- 1877–1886 Sir James Johnstone[c]

- 1886 (6 weeks) Trotter (acting)

- 25 Mar 1886 – 21 April 1886 Walter Haiks (acting)

- 1886 – 24 April 1891 St. Clair Grimwood (d. 1891)

- 1891 Sir Henry Collett (British commander)

- 1891–1893 H.St.P. John Maxwell (1st time)

- 1893–1895 Alexander Porteous (1st time)

- 1895–1896 H.St.P. John Maxwell (2nd time)

- 1896–1898 Henry Walter George Cole (1st time) (acting)

- 1898–1899 Alexander Porteous (2nd time)

- 1899–1902 H.St.P. John Maxwell (3rd time)

- 1902–1904 Albert Edward Woods

- 1904–1905 H.St.P. John Maxwell (4th time)

- 1905–1908 John Shakespear (1st time)[d]

- 1908–1909 A.W. Davis

- 1909–1914 John Shakespear (2nd time)

- 1914–1917 Henry Walter George Cole (2nd time) (s.a.)[clarification needed]

- 1917–1918 John Comyn Higgins (1st time)

- 1918–1920 William Alexander Cosgrave

- 1920–1922 L.O. Clarke (1st time)

- 1922 Christopher Gimson (1st time) (acting)

- 1922–1924 L.O. Clarke (2nd time)

- 1924–1928 John Comyn Higgins (2nd time) (s.a.)

- 12 Mar 1928 – 23 November 1928 C.G. Crawford

- 1928–1933 John Comyn Higgins (3rd time) (s.a.)

- 1933–1938 Christopher Gimson (2nd time) (s.a.)

- 1938–1941 Gerald Pakenham Stewart (1st time) (Japanese prisoner 1941–45)

- 1941–1946 Christopher Gimson (3rd time) (s.a.)

- Dec 1946 – 14 August 1947 Gerald Pakenham Stewart (2nd time)

British administrators

During the princely state stage (1891–1947), an

- May 1907–1910 William Alexander Cosgrave[45]

- April–June 1910 C. H. Bell

- June 1910–1917 John Comyn Higgins

- 1917–1918 Robert Herriot Henderson (1st time)

- 1918–July 1918 V. Woods

- 1918–1919 Sir Robert Herriot Henderson (s.a., 2nd time)

- 1919–1921 Christopher Gimson[48]

- 1921–June 1921 William Shaw

- June 1921 – September 1922 Charles Seymour Mullan

- September 1922 – June 1927 Colin Grant Crawford

- June 1925 – February 1926 Hugh Weightman (acting)

- June 1927 – 1930 Anthony Gilchrist McCall

- 1930 – February 1933 Cecil Walter Lewery Harvey

- February 1933 – February 1936 Gerald Pakenham Stewart

- March 1936 – February 1937 Crispin Bernard Chitty Paine

- February 1937 – 1939 Alexander Ranald Hume MacDonald

- July 1939 – 1943 Thomas Arthur Timothy Sharpe[49]

- May 1943 – November 1945 Edward Francis Lydall

- November 1945 – 14 August 1947 Francis Fenwick Pearson(designated Chief Minister from 15 July 1947)

Indian administration

- Political agents

The

- Dewans

The Dewans were representing the

- 1948 – 16 April 1949 M. K. Priyobrata Singh (s.a.)[50]

- 16 Apr 1949 – 15 October 1949 Rawal Amar Singh[51]

Flags

The State of Manipur had a set of two flags, a white one and a red one. All featured the Pakhangba dragon in the centre, although not as prominently in the latter flags.[52]

|

|

|

See also

- History of Manipur

- Manipur State Constitution Act 1947

- Meitei inscriptions

- Ningthouja dynasty

- Meitei mythology

- Political integration of India

Notes

- ^ William MuCulloch authored Account of the Valley of Munnipore and of the Hill Tribes (1859).[41]

- ^ Robert Brown authored Statistical Account of the Native State of Manipur and the Hill Territory under Its Rule (1874).[42]>

- ^ James Johnstone authored My Experiences in Manipur and the Naga Hills (1896).[43]

- ^ John Shakespear authored The Lushei Kuki Clans (1912).[44]

References

- ISBN 978-1-78673-987-2.

Ghose maintained that under the Indian Penal Code only subjects of the Queen or foreigners residing in British India could be guilty of waging war against the Queen. Manipur was an independent sovereign state and..

- JSTOR 44233143.

- ^ Sen (1992), p. 17

- ISBN 978-0-521-88992-6.

- ISBN 978-81-926687-2-7.

- ^ Fantz, Paul R.; Pradeep, S. V. (1995). Clitoria (Leguminosae) of South Eastern Asia.

- ^ https://press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V2_B2/HOC_VOLUME2_Book2_chapter18.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- S2CID 157167951.

Historically, Manipur was an independent kingdom ruled by Meitei dynasty. The physical boundary of Manipur has been fluctuating with historical changes in political power and the intra state and the inter state boundaries

- JSTOR 26552717.

Both Manipur and Burma succeeded in maintaining their status as independent princely states until the British occupation by in the last part of 19th century

- JSTOR 44158255.

- ISBN 978-0-521-79914-0

- JSTOR 41931038.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 582.

- ISSN 1556-5068.

- JSTOR 44145476.

- ^ ISBN 978-8124109021

- ^ Nath, Rajmohan (1948). The back-ground of Assamese culture. A. K. Nath. p. 90.

- ^ Laichen 2003, pp. 505–506.

- ^ Comprehensive history of Assam, SL Baruah. pp. 296–297.

- ^ a b c d e f "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 17, page 186 – Imperial Gazetteer of India – Digital South Asia Library". Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^

Phanjoubam, Pradip (2015), The Northeast Question: Conflicts and frontiers, Routledge, pp. 3–4, ISBN 978-1-317-34004-1: "After comprehensively defeating the Burmese in 1826 in Assam and Manipur, and the signing of the Treaty of Yandabo, the British annexed Assam, but allowed Manipur to remain a protectorate state."

- ISBN 978-0747803881, p. 62

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/101006. Retrieved 11 October 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ Ethel St. Clair Grimwood, My Three Years in Manipur and Escape from the Recent Mutiny (fl.1891)

- ^ a b "Indian Princely States K-Z". Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ Pum Khan Pau (2012) Tedim Road—The Strategic Road on a Frontier: A Historical Analysis, Strategic Analysis, 36:5, 776-786,

- ^ a b Subramanian, K. S. State, Policy and Conflicts in Northeast India. Routledge & CRC Press. pp. 31–32.

- JSTOR 4410908

- ^ JSTOR 42748891

- ISBN 9781317270669, retrieved 14 January 2021

- ^ Why Pre-Merger Political Status for Manipur: Under the Framework of the Instrument of Accession, 1947, Research and Media Cell, CIRCA, 2018, p. 26, GGKEY:8XLWSW77KUZ: "Before the controversial merger, both Manipur and India were bound by the Instrument of Accession (IOA) which the King of Manipur signed on 11 August 1947. The IOA was accepted by the Governor General of India Lord Mountbatten on 16 August 1947 vide Home Department, Government of India file no A-1/1/1947. Subsequently, the Manipur State Council approved the IOA in its meeting held on 22 August 1947 Vide Memo No. 383 PTI Reference Council Minutes Part I of 11-8-1947. The execution of the Instrument of Accession was published in the Manipur State Gazette on 27 August 1947."

- ^ Sudhirkumar Singh, Socio-religious and Political Movements 2011, p. 139; See Chapter 2 for the limitations of sovereignty under the colonial regime.

- ^ "Instrument of Accession of the State of Manipur" (PDF). Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ Sudhirkumar Singh, Socio-religious and Political Movements (2011), Chapter 6, p. 145.

- S2CID 153661583.: "The Maharajah of Manipur was invited to Shillong in September 1949 for talks on integration.... The Maharaja was placed under house arrest and debarred from any communication with the outside world. The Maharaja was thus forced to sign the ‘Merger Agreement’ with India on September 21, 1949, and Manipur became a 'Part-C state' of the Indian Union."

- ^ ISBN 978-0330396110

- ^ Agnihotri, Constitutional Development in North-East India (1996), p. 68.

- ^ "MANIPUR". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ Thokchom, Princely State of Manipur (2022), Appendix IV.

- ^ "Page:Dictionary of National Biography volume 35.djvu/27 - Wikisource, the free online library".

- OCLC 249105916– via archive.org.

- ^ Brown, R. (1874), Statistical Account of the Native State of Manipur and the Hill Territory under Its Rule, Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing

- ^ Johnstone, Sir James (1896), My Experiences in Manipur and the Naga Hills, London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company – via archive.org

- ^ Shakespear, J. (1912), The Lushei Kuki Clans, London: McMillan and Co – via archive.org

- ^ a b Singh, History of the Christian Missions in Manipur (1991), p. 9.

- ^ Sudhirkumar Singh, Socio-religious and Political Movements (2011), pp. 49–50.

- ISBN 978-0-230-27061-9

- ^ C Gimson 1955-56, Leicester Literary and Philosophical Society.

- ^ Thokchom, Princely State of Manipur (2022), p. 10.

- ^ a b c Sudhirkumar Singh, Socio-religious and Political Movements (2011), pp. 139–140.

- ^ Sudhirkumar Singh, Socio-religious and Political Movements (2011), pp. 141–142.

- ^ "Manipur". Retrieved 1 April 2015.

Bibliography

- Laichen, Sun (2003). "Military Technology Transfers from Ming China and the Emergence of Northern Mainland Southeast Asia (c. 1390-1527)". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 34 (3). Cambridge University Press: 495–517. S2CID 162422482.

- Agnihotri, S. K. (1996), "Constitutional Development in North-East India since 1947", in B. Datta-Ray; S. P. Agrawal (eds.), Reorganization of North-East India Since 1947, Concept Publishing Company, pp. 57–92, ISBN 978-81-7022-577-5

- Sen, Sipra (1992), Tribes and Castes of Manipur: Description and Select Bibliography, Mittal Publications, ISBN 81-7099-310-5

- Singh, Karam Manimohan (1991), History of the Christian Missions in Manipur and Neighbouring States, Mittal Publications, ISBN 81-7099-285-0– via archive.org

- Sudhirkumar Singh, Haorongbam (2011). Socio-religious and Political Movements in Modern Manipur 1934–51. INFLIBNET (PhD thesis). Jawaharlal Nehru University. hdl:10603/121665– via Shodhganga.

- Thokchom, Veewon (2022). Princely State of Manipur: Durbar, the Raj and Resistances, C. 1900-1950 (PDF) (M. Phil. thesis). Aizwal: Department of History & Ethnography, Mizoram University.

Further reading

- Joychandra Singh, L. (1995), The Lost Kingdom: Royal Chronicle of Manipur, Prajatantra Publishing House

External links

- Territorial Councils Act, 1956, Lok Sabha Bills, retrieved 25 November 2020.

- Seven clans of Manipur

24°49′N 93°57′E / 24.817°N 93.950°E

- Government of Manipur (1949). Manipur Gazette, 1949, January–June. pp. 1–5.

- Hosting sites of FOTW, National Flag